The cheekiest Tour stage win

We have to go back to the start of the Swinging Sixties, literally the start because this is the...

Tales from the peloton, May 28, 2008

We've all known the feeling. The race is coming to an end and you sense that, even if you're not going to win, something's going to go right for you. And then you feel your rim bumping along the road. You know that sensation? Well, this is a story to bring you fresh heart when it happens to you... Cyclingnews' Les Woodland recounts how one rider's misfortune turned lucky.

We have to go back to the start of the Swinging Sixties, literally the start because this is the Tour de France of 1960. Sharpeville is a town the world suddenly knows because South African troops have fired on an African gathering; an American spy plane has been shot down over the Soviet Union and the world Summit is off; Britain has just made its last steam engine... and the Tour is making its last run with national teams.

In France Charles De Gaulle was the epitome of French hautocracy, a giant president blessed with a wonderfully large nose with which to look down at the rest of the world. A patriot, a pragmatist and a bit of a bike fan, the general. When someone asked what he thought of news that perhaps Jacques Anquetil took dope to help him win the Tour, he answered with words to the effect of: "And what does that matter if it makes the world watch the French flag flying?"

Charles de Gaulle spent his working week in the Élysée in Paris and his spare time in a village called Colombey-les-Deux-Églises, where he lived with his dowdy wife and drove her crazy by playing military music on the record player all day.

On Saturday, July 16, 1960, two days after Bastille day, Colombey-les-Deux-Églises was on the route of the Tour as it headed from Besançon to Troyes. To the French in and around the race, it could only be that the choice was deliberate. Nobody much else knew or cared, as we'll see.

Coming down the road towards the village, word spread that the General had stretched his long legs and walked down to the roadside, where he was standing along with housewives in aprons and the men in vests. The organiser, Jacques Goddet, turned to the gendarmes accompanying the race and asked what they knew. They knew nothing. De Gaulle, at the weekend, considered himself a private citizen no more obliged to explain his plans than anyone else.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Goddet couldn't run his race that way, though, if the president was likely to be beside the road, and so he sent an official, Élie Wermelinger, up the road to have a look. There was plenty of time; the race was just ambling along.

"Call me on the race radio," Goddet told me, "and if that isn't powerful enough then get a gendarme to do it for you."

The news reached the Tour just as the national champion, Henry Anglade, was at the back of the field. Goddet turned to his co-organiser, Félix Lévitan to ask his opinion, then turned to Anglade and shouted the same question: "Do you think the riders would find it inconvenient to stop and say hallo?"

Anglade was astonished. Stop the race in full flight, a race full of many nationalities other than the French, to shake hands with a French politician however famous? It hardly seemed likely. But Anglade put it to the team leaders and got their agreement, then moved back the other way, spreading the message in Chinese whispers through the field. Finally he reached Goddet's red car and gave him the news: the Tour would indeed care to meet the president.

"It didn't make much difference to the race," Goddet recalled, "because there was a sort of truce going on and the field was more or less neutralised anyway. It wasn't going to change the results in any way."

Goddet waved his arms as the race entered Colombey, brakes squealed, the bunch stopped and there at the foot of his garden was De Gaulle. Not just your ordinary weekend in the country, mind, because there with him were an admiral and De Gaulle's minder, Roger Tessier.

De Gaulle picked out the blue, white and red of Anglade's championship jersey, then the maillot jaune of the Italian Gastone Nencini, and followed up by walking round the bunch shaking hands.

"I am very flattered," he said. "I do hope I haven't caused you too much inconvenience."

The halt lasted only a few minutes. The Spanish riders didn't understand and came to the conclusion that it was a political protest of some sort, or if not that then a strike had been called and they hadn't been able to grasp why. Two or three Belgians, to whom De Gaulle was no more significant than any other foreign politician, ran round behind the crowd and had a pee. But one rider was missing. And he too didn't know what was going on.

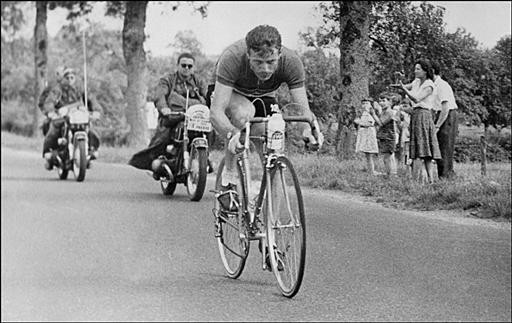

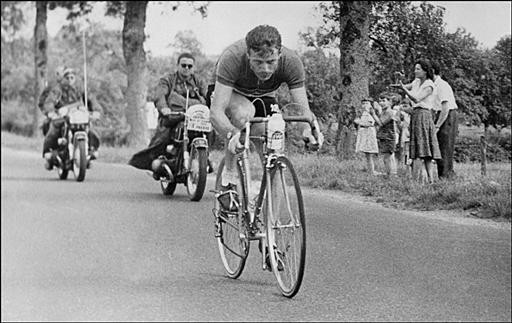

Just a few kilometres before Colombey, Pierre Beuffeuil had felt his rim start bumping on the road. Riders go off the back all the time to have mechanical faults attended to and there's rarely any fuss unless it's a big name. And Beuffeuil, for all it's difficult to spell, wasn't a big name. More than that, at the relaxed speed the race was going, he wasn't going to have to chase back terribly hard.

The mechanic changed his wheel and he set off through the wake of the Tour. He still hadn't made it back by Colombey. When he got there, he saw the whole race standing in the road. If De Gaulle was surrounded by villagers, Beuffeuil may not even have guessed what was going on. But one thing is sure: he saw his chance.

He put his head down, raced up the road... and won the stage. Promising, no doubt, to vote for De Gaulle at the next election to thank him for his chance.

Of all the stages in nine decades of the Tour, his must be the least credible and most cheeky. Never before, never since, has anyone won against a field that wasn't even riding. He dined out on the story for years.