The 1998 Tour de France: Police raids, arrests, protests... and a bike race

Looking back on the Festina Affair and the three weeks that almost brought the Tour to its knees

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The 1998 Tour de France was won by Marco Pantani, but it will always be remembered for police raids, arrests, rider protests and the definitive exposure of widespread doping in the world's biggest race. In this feature, the latest in our 'I love the 1990s' series, journalist and author Jeremy Whittle reflects on those three crazy weeks, which almost brought the sport's greatest event to its knees.

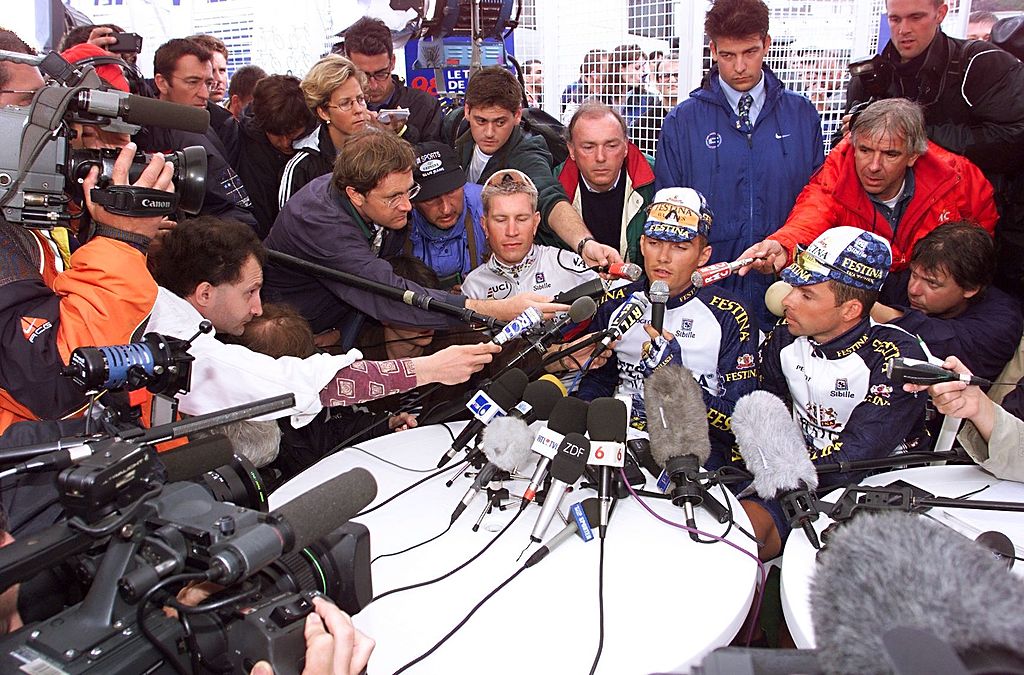

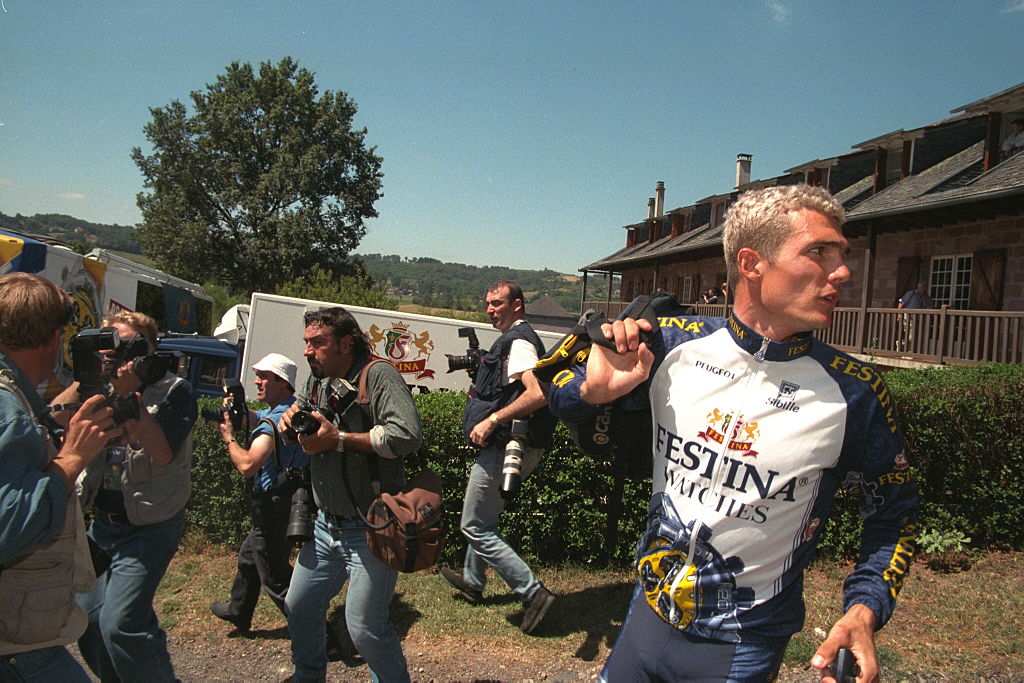

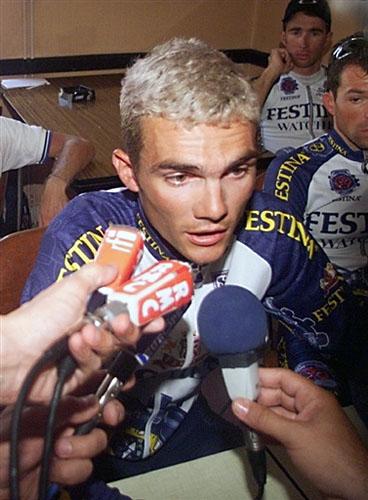

Laurent Jalabert was fuming. He was sick of it, he said, sick to the back teeth. Sick of the media sticking their microphones in his face, sick of the police raids and the constant suspicion, sick of the jeering and the booing.

"Whoever wins this Tour will be the 'King of the Dopers'," he raged as he got off his bike one final time to quit the 1998 Tour de France. A few yards away, his ONCE sports director Manolo Saiz was making his valedictory comments to the media.

"I have shoved my finger up the Tour's arse," Saiz said succinctly as he turned his back on the Tour and took his team back to Spain. As Saiz exited, he led a walkout of Spanish teams and, in a show of solidarity, most of the Spanish press.

Earlier that day, in Albertville, the bleary-eyed TVM team had led a start line protest. They, in turn, were angry over their treatment by the French police who had raided their hotel the night before and taken both riders and staff into custody.

"The police were acting like Nazis," said one member of TVM staff.

By now – the 1998 Tour’s third week – such events had become de rigeur. Kick-started by the Festina team’s earlier eviction during week one, the TVM swoop was the latest raid after those on the ONCE, Telekom, BigMat, and Casino teams. Most raids were accompanied by day and night media stake-outs in car parks, hotel bars and lobbies.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

After the Spanish walkout, with the Tour close to collapse, the unthinkable seemed possible. Could the race even make it to Paris? During that final week, it often seemed unlikely.

But then the 1998 Tour de France – dominated by the Festina Affair – was hardly a bike race at all. Sometimes it was more like being caught up in a 'happening', a cultural event, characterised by serial stand-offs and sit-downs, police raids and petulance, finger-pointing and four-letter words. It was the lead story on French TV news bulletins for the best part of three weeks.

At the time, l'Affaire Festina seemed to be the scandal to end all scandals, an exposé of ingrained doping so cataclysmic that French newspapers even pondered if the Tour should be abandoned for good, labelled anachronistic, a discredited relic. It was also the scandal that accelerated the founding of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA).

It felt at the time like the scandal that could break the grip of doping on cycling, perhaps even on all sport. But that proved extremely naïve.

The hysteria that characterised the Festina scandal was repeated time after time – the expulsion of Marco Pantani from the 1999 Giro d'Italia, the San Remo blitz, the feeding frenzy in Strasbourg as Operación Puerto exploded, the midnight escape from Pau by Michael Rasmussen, USADA’s Reasoned Decision on Lance Armstrong. Festina was merely the first of many. Now, almost 20 years on, it’s reasonable to ask how much has really changed.

Photo: Getty Images Sport

I was also there to cover the race for The Times. But, as the race neared Paris, one of my editors had even questioned the wisdom of covering cycling anymore.

"It's a joke – worse than wrestling really isn't it?" he said. I returned home exhausted and confused, assuming that I'd covered my last Tour and that the race was finished.

The 1998 Tour had left the Grand Départ in Ireland to cross to Brittany, bathed in an atmosphere of celebration after France's win in the 1998 World Cup final in the Stade de France. There was a story bubbling away about a Festina soigneur, detained by customs in Belgium, but the jubilation of the World Cup victory temporarily swept it away.

But that happy vibe quickly evaporated once the peloton arrived on home soil and the speculation over doping grew. In its place, came the denials and counter-accusations, with the conflicted and hesitant Tour director Jean-Marie Leblanc blaming the press for “stupid rumours”.

Even though their glory years were long gone, French professionals still had a sense of entitlement when it came to the Tour. Despite the success of Germany's Telekom sponsorship, through Bjarne Riis and Jan Ullrich, the Tour was yet to become globalised – that would happen with Lance Armstrong’s first win a year later. On home turf at least, the 'Dons' of French racing still considered themselves 'Untouchables'.

Jalabert, Richard Virenque, Jacky Durand, Christophe Moreau, Pascal Herve, Laurent Brochard, Philippe Gaumont, Luc Leblanc – these riders were all ratings winners, household names, French all-stars. They'd made a deal with the French public – whether they were watching on TV or standing at the roadside — to show panache.

July, then, was show time, when France expected them to race with style and to give the home fans hope, even if it was an empty, futile hope. The greatest exponent of this was Festina leader Virenque, who, fully aware of his limitations as an overall contender, played to the gallery at every opportunity.

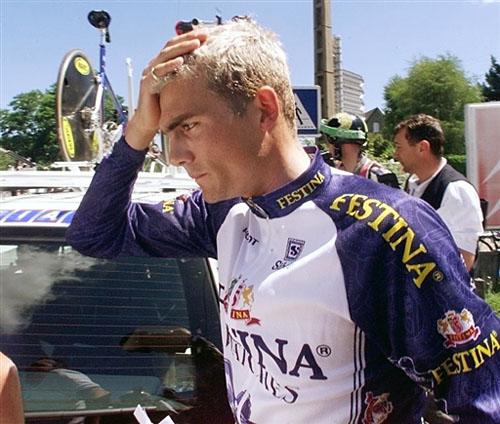

The scandal that began with Festina soigneur Willy Voet's arrest only really gathered pace after team manager Bruno Roussel's admission of a structured doping programme. Once Tour director Leblanc learned the truth – that Roussel had overseen a coordinated doping programme managed by his medics – the team was evicted.

Virenque's sense of theatre even extended to his protestations of innocence and his denials of doping. There were tears, and a man-of-the-people statement from the back room of a bar-tabac in Correze, where – incredibly – Tour boss Leblanc popped in to offer his condolences, even as Virenque bid farewell.

Photo: Getty Images Sport

Looking back, I can hardly remember any racing beyond Pantani's slaying of Ullrich on the road to Les Deux Alpes. I remember watching Ullrich cross the finish line, puffy-eyed and feeble, a spent force, held up by teammates Bjarne Riis and Udo Bolts. I remember, too, his Lazarus-like resurrection on the next day's climb of the Madeleine.

And I remember queuing late one evening in a McDonalds in Pontarlier, where a well-known and still active directeur sportif, who should have been with his riders in their hotel back across the border in Switzerland, met a man driving one of the caravane publicitaire’s refrigerated drinks vans.

Perhaps the biggest irony was that Lance Armstrong, post chemotherapy, was back at the Tour, working for American TV as a guest pundit. I saw him standing on his own among the miles of spaghetti – the wires and cables in the broadcast zone – even as Pantani, Bobby Julich, and Ullrich rode the final time trial from Montceau-les-Mines to Le Creusot.

We chatted briefly and he told me about his plans to ride that year's Vuelta a España. He was optimistic for his comeback. The next day, Pantani was crowned Tour champion in Paris. Of the 189 starters, only 96 finished the race.

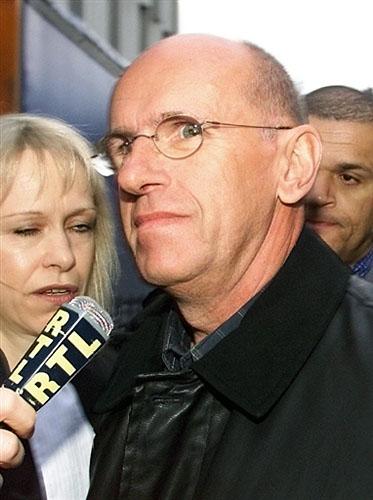

After I returned home from the 1998 Tour, a letter arrived from Switzerland. It was from Hein Verbruggen, President of the UCI, who said he was writing on behalf of the UCI and Jean-Marie Leblanc. Verbruggen had been on holiday in India during that year's Tour.

The President wasn't happy. I was a 'demagogue', Verbruggen claimed, and my articles during that July had been inaccurate and wrong, with too great an emphasis on doping, rather than sport.

Despite the hand wringing and gnashing of teeth in the aftermath of Festina, the Tour clung onto life after all. At the usual route presentation for the following year's race, Jean-Claude Killy said that the 1998 Tour had survived because it was "so great".

"Because the Tour is so great, it lives on," Killy said. "Because it lives on it will never again be the symbol of doping, but a symbol of the war against doping. We will never give up the fight against doping."

The audience in the Palais des Congres in Paris applauded loudly. The following July, Lance Armstrong, leading the US Postal Service team, was back on the Tour's start line, for what they labelled 'The Tour of Renewal'. This, then, post-Festina, was the Tour’s Brave New World.