Team time trial mixed relay and the debate around co-ed racing - World Championships

New event sparks debate about the future of women's racing

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

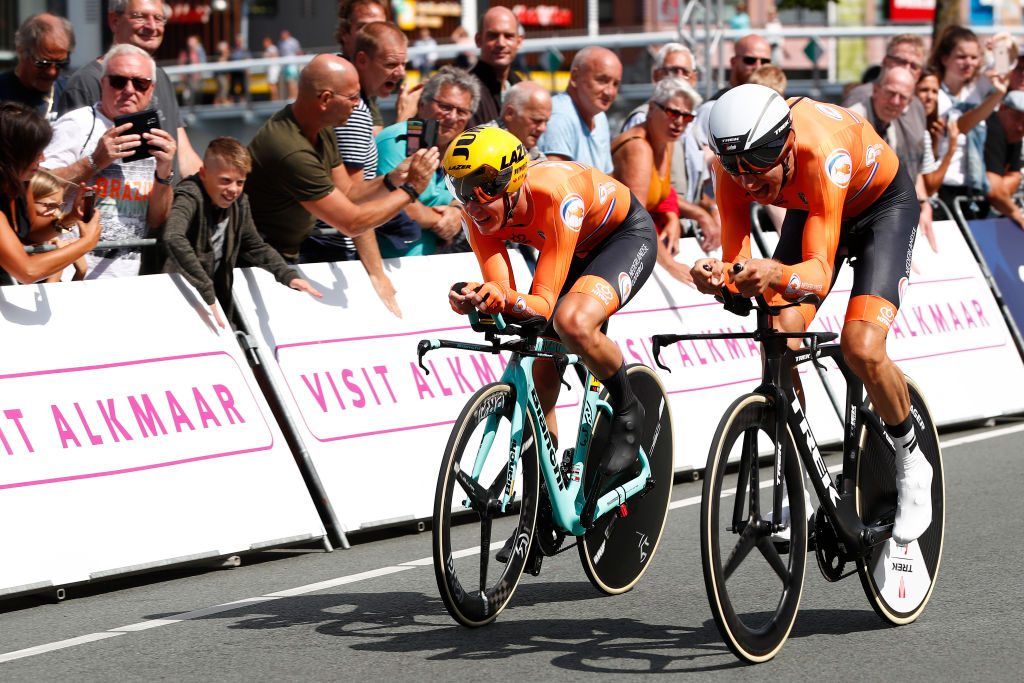

The Team Time Trial Mixed Relay made history on Sunday as the first mixed gender event ever held at the UCI Road World Championships. It replaces the Team Time Trial, ridden by trade teams, which had been a World Championship fixture since 2012. The new event features national teams of professional and U23 riders, consisting of three male and three female riders.

The men set off together to ride a short first lap (on Sunday it was the technical 14km Harrogate circuit), and when the second man crossed the line, it was the women’s turn to do exactly the same thing. The team’s overall final time is taken when the second woman crossed the line.

When the UCI president, David Lappartient, announced the event last year, he called it "the latest step towards greater gender equality in cycling."

But is it a great leap forward for equality in women’s and men’s racing, or—as some critics have suggested—a somewhat ill conceived publicity stunt designed to appeal to the International Olympic Committee?

Are mixed men’s and women’s races feasible or even desirable, and do they have a future in professional cycling?

Initial reactions

To no-one’s great surprise, the Dutch team won. In terms of fielding riders, they have an embarrassment of riches to select from: Dutch women dominate on just about every level in women’s road racing, the men are famously tough and hard-working, and there’s no shortage of up and coming champions, and are well supported with national coaches and organised training camps.

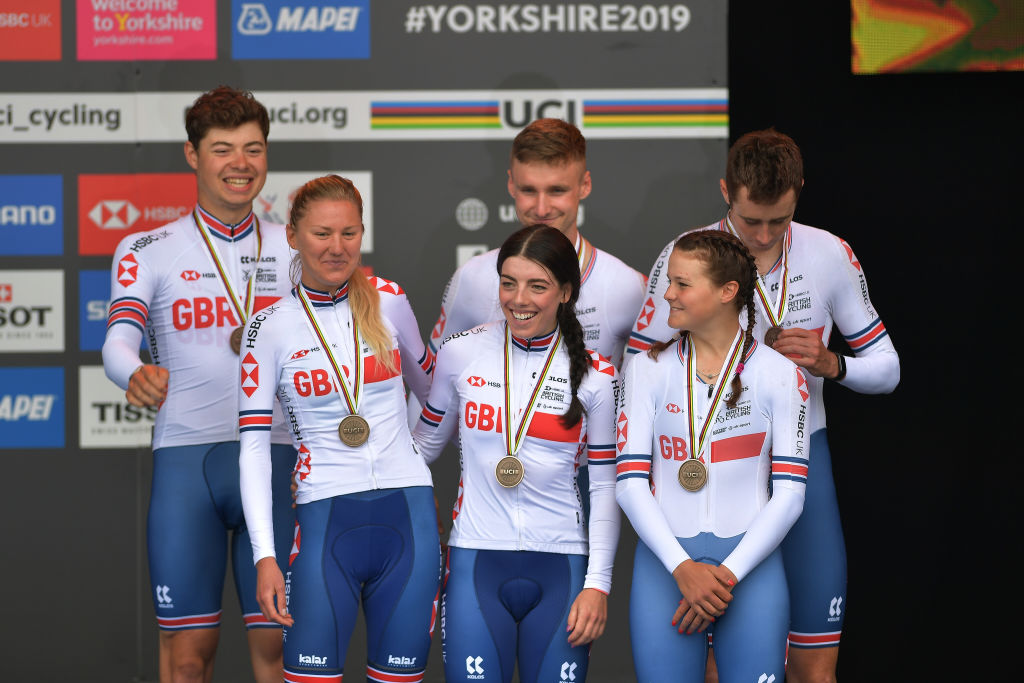

Their closest rivals were the Germans, who came second, while - perhaps appropriately enough given Britain’s history in the discipline - the home team came third. But apart from the almost foregone conclusion the Dutch would win, no one really had any idea how the rest of the event would go, and that wasn’t just because of the technical course or the Yorkshire weather that was primed for ambush.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The mystery element was the event itself, which bears so little resemblance to the old TTT, or indeed to any other type of race, that it calls for an entirely new approach.

"It’s something new and we have to try it and figure it out," said Loes Gunnewijk, head coach for the Dutch women’s national team ahead of the race.

"It’s harder in a different way. Normally you have six riders and you are allowed to finish with four. But now you have two teams of three riders and you have to finish with two. There’s less time to recover between pulls."

That means a team has to think very carefully about whether to drop a teammate who can’t hold the pace, when there’s a risk that one of the remaining two riders might also run out of steam or suffer a mechanical. The shortness of the course only adds to the intensity of these ‘should-we-stay-or-should-we-go’ decisions, with riders already turning themselves inside out to maintain a super fast pace in the knowledge that only a matter of seconds may determine the final ranking.

As we saw on Sunday, this made for some nail biting racing, in particular for the Italian team, who lost third place on the podium when Elisa Longo Borghini suffered a puncture. Her two teammates pressed on ahead while she waited what felt like an age for a new bike. Against all rational expectations, she rode her way back to her teammates, caught them on the closing straight and then catapulted forward, towing them to the finish—only to lose out to the British by five seconds.

"I’ve never seen someone dropped on a team time trial who no one was waiting for come back in such style," said an astounded Jacky Durand, commentating on French TV.

The Italians would be justified in feeling especially bitter about their bad luck, following their experience at the European Championships in August, when the race format was tried for the first time. On that occasion the German and Italian men’s teams had been neck and neck for second place, but the Italian women lost time when they appeared to wait for their third rider who struggled to hold the pace. They presumably decided on Sunday not to make that mistake again. Sadly, given the form Longo Borghini was in, they would probably have done better to wait.

There were other parts of the race that were confusing, such as the fact the men finished in a different spot to where their female teammates started, making the race feel more like two separate events rather than an actual relay. Based on the Dutch team’s experiences already in August, Gunnewijk expressed her concerns about the professionalism in certain details of the format, in particular with the potential for a messy handover.

For spectators, there was plenty of fun to be had in number-crunching and comparing the men’s and women’s intermediate times in addition to those of the team as a whole, though what you really wanted was a graph or a chart at the bottom of the TV screen with all the data to hand. In the end, it was hard to keep on top of who’d done what. For the riders, however, especially on the teams that didn’t have a particularly strong female element, the new format risks being painfully humiliating. Witnessing the Slovenian women’s team fall apart felt particularly cruel.

But even the winners, spellbinding with their consummate control and power and their seamless handovers, offered a reminder that anything could happen, when Bauke Mollema briefly touched his teammate’s wheel. Had they crashed they would undoubtedly have lost the 23 seconds that ultimately separated them from the Germans.

"It's amazing. So fantastic to be world champion here," Mollema said after the finish.

"It was so hard to do a TTT with three riders, so much harder than with seven or eight. The course was really hard with the rain, it was technical and up and down. I think we did a really good performance. Jos Van Emden and Koen Bouwman were pulling so hard. The women did an amazing job as well. We won! It was really nice."

Mixed sports

Though not always mainstream, mixed gender sports are nothing new.

As early as 1900 there were mixed events at the Olympics in tennis, sailing, equestrian events and even croquet, while pair figure skating featured at the first-ever winter Olympics in 1908.

Over the last couple of decades many other sports have been introducing mixed formulas. Biathlon introduced a mixed event in 2005 with the ambition to bring more women into a male-dominated sport, triathlon introduced a mixed event at the world championships in 2009, in swimming there have been mixed relays since 2014 and there are many more sports besides, from track to judo to cross country skiing which are creating new ways of getting male and female athletes competing together. Closer to road racing, there are mixed events in mountain biking and BMX.

In 2017 the International Olympic Committee upped the ante by introducing its Gender Equality Review Project with the ambition to create an equal gender balance across all Olympic sports. As a result, the 2020 Olympic games in Tokyo will feature 18 mixed events compared to the 9 held at Rio in 2016. Mixed events are just one part of the IOC’s ambitious strategy, which also calls for more women’s events and seeks to get more women involved at all levels, whether they are athletes, coaches or administrators.

The Gender Equality Review Project is part of a bigger drive to attract younger viewers, alongside the introduction of more youthful and urban sports. In order to achieve these goals and create room for these new events, many men-only events across a number of sports are being dropped entirely from the Olympic programme, or being given to women instead.

Responding to emailed questions last week, UCI President David Lappartient declared that, “gender equality is key in our federation's roadmap Agenda 2022” and he pointed to progress made, “on the front of athletes’ participation,” and in terms of prize money at UCI Championships and World Cups. (In 2017 the UCI introduced prize parity, after Lizzie Deignan revealed that she had received £2,000 for winning the women’s World Championship Road Race in 2015, whereas Peter Sagan received £20,000 in the men’s event.)

“Based on the experience in Yorkshire, which we’re sure will draw a great deal of enthusiasm from the fans,” he added, “we’re ready to consider, together with the International Olympic Committee (IOC) if it so wishes, the possibility of a future inclusion of this new innovative format at the Olympic Games as part of the existing road cycling programme. This event would be perfectly in line with our objective of total gender parity at the Paris 2024 Olympic Games with the aim of male and female cyclists enjoying an equal number of quotas, events and medals.”

Inevitable controversy

With such a radical change, it’s not surprising the new format has attracted criticism.

"There’s no need to introduce Mickey Mouse events," Mitchelton-Scott DS Matt White declared last year. "We already had two very good events, the women’s and men’s TTT."

"This is just an exposition, it’s not a real competition," said Deceuninck-QuickStep boss Patrick Lefevere, whose team won last year’s men’s race. While insisting he had, "nothing against women cycling," he said, "I don’t think it’s a sport to be mixed with men. It’s not an honest competition.

"I’m afraid if the men are too strong and they lose they are going to [look] at results of the women. If they put in the best time and the women’s team loses too much time then they will say, ‘You see, we lose because the women’s team was too weak.' Or vice-versa."

Though that ‘vice-versa’ did in fact take place on Sunday with the German women posting a much stronger relative time to the men, Lefevere talking in terms of the women letting down the men does add another layer of meaning to the expression ‘race of truth’. For as it became abundantly clear on Sunday, the event ultimately offers a ranking of the federations that are the most supportive of their female riders. Where the disparities between the men and women were most pronounced (while subtracting time lost to punctures), one can probably assume the federations in question have treated their female riders as an afterthought. The pity is that in the visceral moment of the race itself, it’s the women who are made to look bad.

Not everyone is as negative about the event as White and Lefevere, however. Martin Vestby, directeur sportif on Mitchelton-Scott’s women’s team, offers a more conciliatory view to his colleague, pointing out that the old TTT was not universally loved.

If it wasn’t one of your team’s strengths, the World Championship TTT was an expensive pain in the neck; why would you spend many thousands of pounds sending your riders to a single event, "for a 10th place that no-one will remember?"

"In one way I miss the proper old-school team time trial, it has something special to it," he says, but on the other hand, "I like the concept where they have both the men and women together."

The problem as far as he is concerned is that it’s a new, untested event. As such, national federations will have difficulty fielding their top riders, who will prioritise their chances of glory in the individual time trial, and without the best riders it’s, "like a second category event."

Indeed, while quite a few big-name riders took part, most of the teams featured younger, up and coming riders. And while the event’s concept was designed to make the national federations happy, not all of them committed, with Australia and the USA notably absent.

Ina-Yoko Teutenberg, directeur sportif of the Trek-Segafredo women’s team, points out that the new event, "benefits the strong nations", whereas, "in the TTT with pro teams there were some people from smaller nations who had a chance of being world champion, and that’s taken away from them."

How spectators and TV audiences respond will be the ultimate gauge of the event’s success, she said.

"I think only TV numbers can tell you if more people tune in because the guys are riding, who might not have watched just the women’s trade TTT.

"For those who don’t know cycling that well and turn on the television, it’s probably more interesting for them to see a mixed relay than a normal Team Time Trial," suggests Vestby.

"You can hope for more stuff happening because there are more factors that can turn around the score. It can turn around completely. That’s probably what the UCI is looking for, that can catch a broader audience."

“It’s not a made-for-TV event,” counters Connie Carpenter-Phinney, winner of the inaugural women’s road race at the Olympics in 1984. Time trialing is part of her family business: between herself, her husband Davis Phinney and their son Taylor, there are more Olympic, world championship and national time trial and pursuit medals than you can possibly fit in one shoebox. Yet this concept leaves her cold.

"It’s really not a relay," she points out.

"A relay is where each leg is usually carried out by an individual. It’s really exciting—think about the 400m relay on the track, where you’re handing up a baton. A relay should be exciting and it should be close at the end, not a time trial. A relay isn’t a time trial, it’s man against man, man against woman, whatever. You could have a fantastic relay event with two men and two women on it, and with a massed start, with the top 12 nations, and have it on a fairly short course. It’s not exciting to have three person teams—nobody races in three person teams, so how do you even train for this? How do you prepare for it?"

For her, the new concept just seems "contrived."

Can women and men race together?

The mixed relay essentially consists of two separate races, with the overall times added up. But could men and women take part in a mixed road race?

The answer to this question is not as straightforward as you might imagine. The assumption is that if you had mixed teams taking part in the Tour de France, say, you would end up with two races, one between the men and the other between the women, who would be quite a bit further behind.

Of course, physiological differences dictate that the very best elite men will always be stronger than the very best elite women, but there are other factors that affect performance.

The Tour brings together the best riders in the world, in peak condition, who, it increasingly seems, are prepared to risk their lives in order to achieve their goals. Bike racing has always been a bit of an arms race, and this is not just a veiled reference to doping: consider extreme diets, wind tunnel tested frames and wheels, disk brakes, the Chris Froome ‘tuck’ that became one of the Tour’s talking points in 2016 and all those other ‘marginal gains’ that riders, sports directors, manufacturers, doctors and nutritionists sweat over. The net result is that we now have insanely high average speeds in men’s racing, with stage 17 of this year’s Vuelta a case in point: at an average speed of 50.63kph, it’s believed to be the fastest bike race over 200km ever ridden.

Women’s racing simply doesn’t have the resources to engage in the same tactics to the same degree. The peloton is smaller, and therefore cannot build the same express train momentum. Most riders have to take on extra jobs to pay the rent, and therefore can’t devote every moment to optimal performance. Teams are smaller, and mostly don’t have the luxury of letting some riders peak for specific races. The differences between men and women can’t simply be reduced to their V02max or power to weight ratios.

But it has been done before...

In the early days of US racing, all the great female riders regularly raced against top male amateurs. They included Audrey McElmury, the first-ever US road race world champion in 1969, Connie Carpenter-Phinney and Inga Thompson, who each represented the strongest riders of three consecutive generations. All three riders would frequently be in the breaks of men’s cat 1-2 races and were capable of finishing in the top ten.

"Cycling was much less regulated in the 80s and 90s," explains Carpenter-Phinney. "There just weren’t a lot of rules around what you could and couldn’t do."

The problem with women’s races in those days, was that there weren’t very many.

"It’s pretty hard to imagine how few women were racing in the 80s, in our big country," she adds. "You would either show up at the starting line with 20 women and just do a time trial with yourself or maybe one other person, or race in a very fast-moving men’s race."

While she points out that she was never a professional, neither, for a long time, was her husband, who was so good at winning races people called him ‘The Cash Register’. During her era, she points out, the Olympics still had an amateur code: so the races Carpenter-Phinney took part in could also feature the best male riders, too, like Phinney, or Alexi Grewal, who won the 1984 Olympics road race. It wasn’t until 1985—a year after his wife retired—that Phinney joined 7-Eleven, the first American professional men’s team to race in Europe.

Inga Thompson recently explained that the top international women’s races she took part in between 1984 and 1993 were, "quite similar in the sense of the speed and intensity," to the men’s races, but the men’s races "were longer and there was more depth." The main difference, she considered, was that in the top women’s races, "I could make more decisive moves and every once in a while get away. But it wasn’t very often that I rode off the front and there were also times with the men where I almost got away."

Even now, Connie Carpenter-Phinney contends, "all the top, top women today could jump into a men’s race and keep up to a certain point. Now men’s races when they’re 230 kilometres long, there aren’t that many women that are trained to go that distance but the top women have the bike handling, the power and the savvy, because sitting in is technical and tactical, it’s not all about power."

On the other hand, she points out, "once you start to go straight up hill, that’s where the power to weight ratio is so important, and there are few women that could climb with the best men for any distance."

One current rider who knows a thing or two about climbing with the men is Annemiek van Vleuten, who this year took part in the Mitchelton-Scott men’s team training camp as a way of preparing for the season and getting back in form after breaking her knee at last year’s World Championships.

"For Annemiek it was really good to get that block of training in that camp, to get out and do proper training and she had to push herself quite hard," says Vestby.

"That’s a good thing when you train with someone who is stronger than you and better than you. You push your limits. That’s a good thing for Annemiek [because] there’s not too many [female] riders on her level."

Other possible mixed-gender race formats

In amateur racing, there are plenty of stories of women and men racing together.

In France in the years before and after the Second World War, there was a thriving mixed tandem-racing scene, which drew hordes of spectators as teams thrashed their way around a circuit, sometimes at higher average speeds than the male pros that rode a professional version of the same race. One of the female stars of that time was called Lyli Herse, who would later become a multiple French national road race champion. Later in life she ran a women’s team, and persuaded the French cycling federation to let elite women race against junior men. It worked pretty well, she said: the women raced hard to prove to the men what they were capable of, the men gave it their all to avoid being embarrassed by the women.

There are other interesting amateur formats that could potentially be adapted to mixed-gender racing. Australia has a long history of handicap races, where riders are given different start times according to their abilities, with the strongest riders starting out last. Meanwhile in track cycling Audrey McElmury used to team up with her first husband, Scott, to compete in Madisons.

Could such events be dusted down and reworked in a professional racing context?

When the question is put to Lappartient, he says: "These are perfect examples of a long history of mixed events in the different disciplines of cycling."

He also signals the mixed gender events in Mountain Biking and BMX at the UCI Mountain Bike Championships and the Youth Olympic Games.

"All these competitions combining male and female athletes, very popular among the fans, show how gender equality can be anchored in our sport."

But are mixed competitions really what’s needed in terms of gender equality?

The mixed relay might offer a potentially fun new format for spectators to watch, but it probably doesn’t do all that much in the end for equality.

Carpenter-Phinney suggests that it would be better to have male and female versions of the same Classics races and to make sure the women’s races get equal television coverage.

Vestby holds up this year’s Clasica San Sebastian race as an example of a race organiser doing this really well.

"It was the first year they put the women’s race on the same day as the men, with all the spectators there. But then they also managed to get it on television."

In doing so they sent out a signal to "all these other races who say it’s impossible to do a men’s and women’s race on the same day and then have the women’s race on television because it clashes with the men’s race and it costs too much money. They showed how it can be done."

But Vestby also argues that women’s races shouldn’t "all be hanging off the back of men’s races."

He points out there are plenty of great women’s events, such as the Women’s Tour, and The Battle of the North, a new Scandinavian stage race that’s in development, that really stand out on their own merits.

Teutenberg for her part points out that the women’s calendar is already quite full, and that rather than worrying too much about tricksy new formats or copying men’s races, it would be better to simply support existing women’s events, many of which have a long and storied history.

Equally important is the need to pay riders fairly, at a time when the annual budget of the average women’s team is less than the salary of just one top male rider. The UCI is taking steps to address this with the introduction of a minimum wage starting next season, but the sport also needs more exposure to help generate the interest that will ultimate fund those teams.

In the meantime, a number of progressive race organisers are starting to introduce equal prize money for their men’s and women’s races, while just this month, thanks largely to former cyclist Kathryn Bertine’s efforts, the State of California passed a landmark Equal Pay for Equal Play bill, requiring parity in prize money for men and women when they take part in the same competitions.

Creating a collegiate culture

One of the striking things in recent years is the number of men’s pro teams that also field a women’s team.

Twenty years ago T-Mobile was the exception. Now, with teams like Trek-Segafredo, Lotto Soudal, Team Sunweb, Movistar, Mitchelton-Scott and Française des Jeux entering the women’s peloton, such teams are starting to become the norm. Does it change the cycling culture?

I asked Vestby whether the men got anything out of van Vleuten joining them on their training camp.

"It’s always nice to have a female around once in a while. I think the conversation changes and the atmosphere changes a bit. But I think seeing how professional Annemiek was and how she approached that camp and what she did was probably also an eye-opener for these guys who hadn’t expected her to be on that level and to be able do all that she did. For us with the men’s and women’s team it’s something that helps bring us even closer together."

Some argue that for women’s racing to evolve, it needs male riders to also voice their support. Seasoned activists will tell you that for any movement to become successful, it needs to enlist supporters from all layers of society, not just its affected base. When a champion of Mark Cavendish’s stature sends out tweets saying Marianne Vos is one of the greatest riders of all time, it changes the conversation.

"I think most of the men really respect the women," says Carpenter-Phinney. "When you’re in Girona, you always see the Aussies riding together, the men and the women. Lizzie Deignan trained with Phil and his group. This is happening. It’s organic. It happens out of necessity, it happens out of friendship, there’s a lot of friendship across the pros, the men and women."

Though no-one would argue it’s the men’s job to advocate for women’s equality, when male pros openly celebrate their female counterparts, it sends a powerful signal to the online forums, newsrooms, pubs and cycling clubs where the sport’s fans are to be found. And it could be argued that by creating a mixed-gender event, the UCI is helping to support this shift in thinking.

A time for soul-searching

"I don’t think the question is for the women to be racing with the men or to merge categories," reflects Carpenter-Phinney. "Listen, the level in women’s cycling right now is as high as it’s ever been, it’s just not seen by enough people. It’s under exposed. And it’s been put down and held down for, well, forever. But why? There’s no reason for it, because when you watch the last hour of a women’s race, it’s as exciting as the last hour of a men’s race."

She can give plenty of examples of how the sport’s governing bodies have come up short.

"I would argue that the UCI gave permission to the race promoters not to include women. And therefore women weren’t included on TV and we lacked exposure. And from that point on we just saw that incredible disparity grow and grow."

She recalls discussions on whether the top men’s teams should field U23 teams, but not on whether they ought to have women’s teams.

"The question isn’t to over regulate," she adds, but whether, "to have regulated at all for the women."

"The UCI legislate how tall your socks are," she points out, but "the only time they ever legislate for the [women’s] sport is when the International Olympic Committee sends down a message saying, 'we need more women in track cycling' or 'we need more parity when we get to the Olympics'."

And so now, she says, the UCI appears to be, "scrambling to try to create the illusion of parity, where parity doesn’t exist."

"I think the solution needs to be more organic and needs some soul-searching from the boy’s club that runs the sport as to what they could do better. Trek now has a women’s team. It took them a very long time to come to the table with a women’s team and I know exactly how that developed.

"And I am so happy to see that. I’m not going to hold a grudge against them for not doing that for so many decades, I’m just going to applaud them for going forward with it. And they can see the benefits, not only for their consumers but for the greater public and also for all those of us who have children who do sports... and many of them are girls.

"I think it takes a lot of soul-searching for the industry and for all the organisations to realise that this is a sport for men and women and that we have held the women back for way too long."