Tadej Pogacar: A life-changing moment captured in a photograph

We watched a man's dream die on live television that day, but at the same time, we watched another man's dream become reality when he least expected it

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Having spent five years as an architecture critic, I think a lot about imagery. It's incredible to me how the framing of an image, the artistic choices made, its contextual setting within a broader work can do so much to amplify, embellish, or change public perception, if not collective memory.

In architecture, for example, the role of photography is interesting, because to really know a building requires viewing it in real life. Architecture is a spatial phenomenon made up of far more than images – there are sights, sounds, smells, perceptions of scale and position in relation to one's own body. To appreciate a building is to be totally embedded in it.

However, for obvious reasons, most of us won't be able to visit the buildings we most want to, least of all because many no longer exist, and so, we rely on images.

A great example of this phenomenon of visual curation can be found in Brutalism, the mid-century architectural style defined by its looming massive concrete forms, the stuff of council housing and government buildings that, because of this context, is often aesthetically divisive in nature. You either love it or hate it and there is no in-between.

Photography tells two different stories of Brutalism. Were I to take a picture of, say, the Barbican Centre, it would prove nothing special; all of the traits of the building both good and bad are just there, unamplified and dull. In my hypothetical iPhone photographs, the Barbican Centre is what it is, an events space slash megadevelopment built in the seventies, aging about as well as ineffectively treated concrete can.

But there are many coffee table books, This Brutal World, Concrete Concept, et cetera, filled with illustrious black and white photographs that highlight the style's positive points – it's utopianism, its sculptural qualities, its daunting scale, the way its massing plays with light and shadow to create great contrasts and a palpable chiaroscuro. Brutalism in these photographs looks less like the poorly aging infrastructure of a gradually shrinking welfare state and more like the inventive, athletic scenes found in science fiction.

Cycling is rather similar in this regard – the imagery makes up so much of the sport. Many of us love bike racing because of the imagery – of sprawling, varied, and often sublime landscapes, of the sleek aesthetics of the bikes and kits themselves, of the drama and passion captured forever on the faces of the sport's practitioners.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

We ooh and ah at the winding switchbacks of the Passo Stelvio and the bald, barren peak of Mont Ventoux just as we are soothed by swashes of Flandrian fields and made anxious by the close intimacy of compressed, sharp hills like the Mur de Huy.

Sometimes, as is the case with the finish of the Tour de France on the Champs-Élysées, the spectacles of cycling decidedly mingle with those of architecture and the city. One cannot separate the picturesque cottages lining the cypress-flanked roads of Tuscany from Strade Bianche.

Like architecture, the act of witnessing a bike race first-hand is an inherently spatial experience, and like architecture, many of us are relegated to having to witness this spatial experience as mediated through the lens of the camera, a lens which very much determines which events are preserved and which are forgotten. Of those that are remembered, the role photography plays can determine the character of the memory, accentuate a narrative, heighten the emotion.

Cycling photography captures some truly incredible moments. One recalls Eddy Merckx in the velodrome gripping the handlebars of his orange self-branded bike, his visage one of total grit and concentration as he attempted and broke the world hour record in Mexico City, or the image of a half-frozen Bernard Hinault staring upwards at the sky during the snowstorm that blanketed the 1980 edition of Liège-Bastogne-Liège, or the face of a devastated Laurent Fignon in the backseat of his team car after losing the final time trial to Greg LeMond in the 1989 Tour de France. For us Americans, we remember Lance Armstrong on boxes of Wheaties at the grocery store.

Even in recent times, the camera has produced its icons. To name just one from our current season, the footage of Egan Bernal unzipping his rain jacket in the final kilometre of stage 16 of the Giro d'Italia to show the maglia rosa for all to see depicted an act of respect for the institution of the race and a testament to his status as its champion.

This image was made all the more special as for much of that stage – one of the Giro's most arduous – the weather knocked out the television stream, which left us all waiting with bated breath for news of, well, anything. To see Bernal emerge alone from the mist under the flamme rouge created a true sense of arrival after so much antsy, mysterious uncertainty.

However, as this year's Tour de France approaches, I've thought more and more about how the story of last year's edition, perhaps one of the most dramatic of this still-young century, was portrayed, how we collectively remember it.

While there were many fantastic stories that unfolded during the 2020 Tour, the one that made it the most memorable was, of course, its ending, that shocking upset on La Planche des Belles Filles, in which the young 21-year-old Slovenian cyclist Tadej Pogačar beat his compatriot and the long-time wearer of the maillot jaune, Primož Roglič, in the final time trial, overthrowing a 57-second deficit and further beating Roglič by just shy of a minute.

This was an event that stunned the cycling world, and I distinctly remember witnessing it unfold on my laptop in my living room, can recall how the scale and the unexpectedness of Roglič's defeat after so much success, if not outright dominance, seemed devastating, almost unwatchable. I still haven't revisited the footage, and even after all these months, I don't know if I can. After all, myself and millions of other people watched a man's dream die on live television.

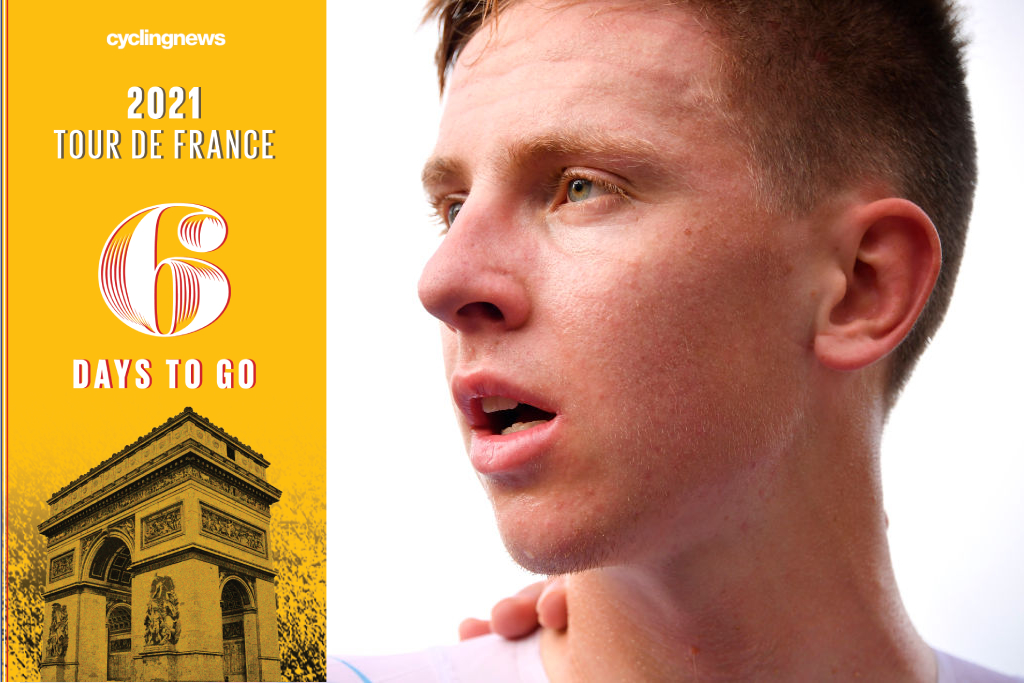

Indeed, this is the indelible image by which we remember the 2020 Tour, the one of Roglič's helpless, agonized face as he crossed the finish line, his helmet askew, his body heaving and lumbering, his eyes haunted by a loss he must have known was imminent. It is a visceral, painful, and very human image. And yet, as I reflect on this moment almost a year later, I think about another image from that day that didn't make the rounds as much, that tells a different side of the story. It's one of Tadej Pogačar taken the instant he's realized he's won the Tour de France.

This small portrait, taken by Getty Images press pool photography Bernard Papon, is just as striking and profound as the one of Roglič arriving at the finish in failure. In the photo, Tadej Pogačar isn't looking at the camera. He's slack-jawed and flushed, gazing outward with shrunken pupils at the scene unfolding before him, a scene that's changed his life irreparably.

The expression on his face is one of pure, unfiltered shock and awe – it is an instant reckoning at what he has done. Not only has he fulfilled his deepest ambition at the young age of twenty-one but, in doing so, he's vanquished a man who is not only his competitor but also his compatriot, a mentor-figure, and even his friend.

As Pogačar said in L'Equipe a few months later, "I had been a Roglič fan since his first results. Between the ages of 15 and 20, I was shouting in front of my television for him to win, and now I was the one who had beaten him, who had denied him from achieving what he had been dreaming of for years… It was really strange. I kept telling myself: 'That's racing, that's sport, it's normal that I want to win'."

As every preview of this year's Tour will prove, Roglič and Pogačar's stories are forever intertwined thanks to that fateful day on La Planche de Belles Filles. And yet, at the end of the day, the 2020 Tour de France was still won by Tadej Pogačar, and he won it on his own merits. It's almost a bit unfair that the younger man's victory is so explicitly tied together with Roglič's loss to the point where it's almost impossible to remember as a stand-alone event earned by the tenacity and consistency of a young cyclist. This is a curse Pogačar shares historically with Greg LeMond, whose Tour de France victories will always be linked to the losses of Bernard Hinault and Laurent Fignon.

The photograph of Pogačar on La Planche des Belles Filles communicates so much so effectively, as successful art tends to do: his boyish youth, his genuine surprise, and, more deeply, a kind of innocence lost, for his world would soon be so very different than it was before he hopped on his time trial bike earlier that day. Cycling is an emotional sport, and this is an emotional image of it, to the point of almost seeming voyeuristic, creating a sense of intimacy with the subject that is lacking in the Roglič photograph, in which the (almost humiliating) presence of the spectator witnessing the event is heavily felt.

In cycling, there is a tendency to prioritize expressions of suffering and ecstasy above all others, and what is so visceral about the moment Pogačar won the Tour de France is that when he crossed the line, he did not know that he had won, and so the joy of victory is not yet present. In fact, there's a sense of malaise, uncertainty, and when the young man comes to his momentous realization, the first emotion on his face is decidedly not happiness but abject disbelief.

To me, this distils so purely the general atmosphere that was present in those immediate minutes after Roglič crossed the line a minute down. One wasn't sure whether to feel sadness for the loser or do the normal, proper, procedural thing and celebrate the winner.

As I said earlier, yes, we watched a man's dream die on live television that day, but at the same time, we watched another man's dream become reality when he least expected it. We watched him make the narrative leap from hopeful young prospect to proven champion of the sport.

We watched his life transform into a more difficult and notable one. We watched him realize his own potential, a potential that still seems boundless. In a way, we also watched him grow up. That, to me, is just as emotional and complex as the unexpected failure of one of cycling's most biographically fascinating characters. That, to me, is just as worth writing about. That, to me, is just as memorable.

Kate Wagner is a Chicago-based writer and critic. Her work on cycling can be found in various publications including Procycling. Her newsletter covers cycling in an unconventional fashion, featuring essays, short stories, multimedia works and illustration.

She can be found Tweeting at @derailleurkate