Student of the sport

Pro mountain biker, student, pro road racer, scholar - at one time or another, Dario Cioni has been...

An interview with Dario Cioni, December 5, 2005

Pro mountain biker, student, pro road racer, scholar - at one time or another, Dario Cioni has been all these things. However, in 2006, all he wants is to graduate to the podium at the Giro d'Italia. Story by Anthony Tan.

2004 changed everything for Dario Cioni. It began in late April with a top five finish at the Tour de Romandie, a race won by American Tyler Hamilton. Then it ballooned into a fourth place finish at the first Grand Tour of the season, the 87th Giro d'Italia. A spot on the final podium at the Tour de Suisse confirmed the previous two were no fluke, before the Italian time trial championship became another addition two days later.

"My position on the team changed completely compared to previous years, because this was the first year I was able to do GC riding without having to look after other riders that much," says Cioni, reflecting on his 2005 season from his home on the outskirts of Florence. "It was really the first year I went to the Tour to do a good GC."

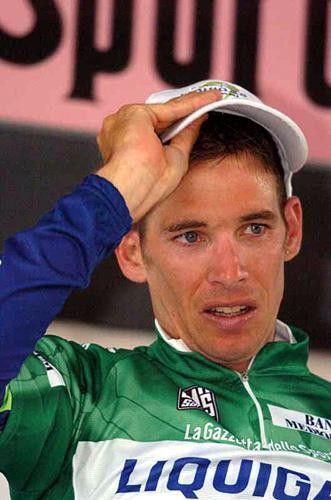

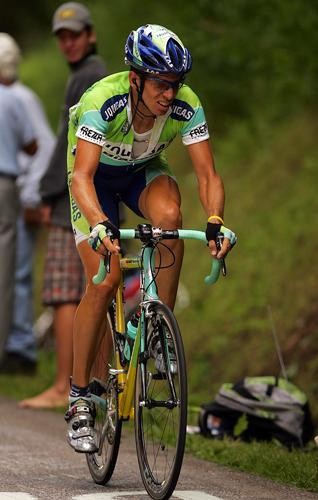

Another significant change was his new home at Liquigas-Bianchi, a 26-strong team of superstars that boasted Danilo Di Luca, Stefano Garzelli, Magnus Bäckstedt and Mario Cipollini in its line-up, who retired just before the Giro. Prior to his arrival, Cioni spent two years at Fassa Bortolo and three at Mapei-Quick Step, the latter where he also rode as a mountain biker from 1994 before his trainer Aldo Sassi asked him to join Mapei's 'gruppo giovane' (young riders' team) in 2000.

While Fassa team manager Giancarlo Ferretti is known as one of the toughest in the business, Liquigas-Bianchi weren't easy on him, either, placing him on the roster for both the Giro and Tour de France this year. Riding two in a row may work for a mature Grand Tour rider like Ivan Basso, but for Cioni, it resulted in both performances compromised.

"My team had chosen a very difficult schedule, which was probably not the best solution for me; you're not able to get into the Giro 100 percent [with his main focus being the Tour de France], and when I got out of the Giro, I was sort of tired and that affected my Tour, especially in the second week where I felt really bad.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"Once I was at the Giro, I gave it everything I had, but I didn't go into the Giro as strong as previous years. I couldn't hit my peak during the Giro or before because of the Tour, but not having the same condition meant I couldn't gain back time in the last week, and that made for a poorer GC placing," Cioni says with a degree of solemnity.

However, his Giro wasn't a disaster. In the end, he still ended up thirteenth overall, and although it wasn't his job, Cioni worked for Di Luca where he could, who lead for ten stages before finishing fourth overall. And if it wasn't for a bad day on the last mountain stage to Sestriere that saw him lose ten and a half minutes to pocket-sized Venezuelan revelation Jose Rujano and drop five places on the general classification, eighth would have been his final resting place in Milano.

"Danilo had a very good GC position and I did what I could to help him, but we are very different riders," he says. "But that didn't affect my performance in the Giro; if I was strong, I could have done my race, anyway. But it just made sense to work together since Garzelli was out due to a back problem. The stage I got second [at the Giro, stage four], if I had won that, my season would of changed results-wise."

Although if one remembers, that fourth stage to Frosinone was riddled with controversy, when the maglia rosa at the time, Paolo Bettini, was disqualified for not holding his line when sprinting, and as most saw it, the Olympic champion put Baden Cooke into the barriers. Realistically, he would have finished fourth that day.

________________________

By the time he got to the Tour, Cioni said he felt fatigued, his heart rate unable to go up despite his team making the top ten in the 67.5 kilometre team time trial from Tours to Blois. "The body was saying: 'Okay, slow down, because I'm tired.'

"Once we hit the mountains, I wasn't as strong as I thought and after the first rest day, things went much worse than expected. I went through a very bad patch, at one stage thinking I would have to quit the race; I just had to say to myself, 'Let's get through this and take it easy'... well, as easy is possible when you're at the Tour," he quips.

"I had better condition in the third week, but it wasn't the best, anyway. Under what I expected and what the team expected, but I wouldn't call it a completely bad season. It wasn't a lucky season, though, that's for sure."

If he were to go into La Grande Boucle again, Cioni says he would skip the Giro altogether. However, the 2006 Tour's not on his racing schedule - and it's something he's comfortable with. "It's sort of hard being on an Italian team and living in Italy," he says. "My best performances have been at the Giro, and it's a race I really feel a lot [of emotions]... it would be hard to skip the Giro next year. But that would be a way to ride a good GC at the Tour."

Cioni may not be riding next year, but believes Lance Armstrong's retirement will make a definite impact on future Tours de France, particularly for Discovery Channel. Up until now, he says, everyone knew there was one team that would take control of the race at one stage or another; next year, with Ullrich, Basso and Vinokourov all capable of winning, there will be at least two or three teams vying for control. "If this doesn't happen, one or two major breaks may affect GC in the following two weeks," Cioni predicts.

"I really didn't go into deep analysis of the course, but the Tour de France courses are always quite similar - it's going to be very hard with a lot of climbing, so I would probably put Basso as one of the main contenders."

Asked on the differences between the two, he begins by saying the ProTour changed the shape of this year's Giro d'Italia, in that the racing was a lot more competitive than before, there were more strong riders, and as a consequence, speeds were higher. "But finishing the Tour is like getting a university degree," muses Cioni.

"All the riders are really keen to get to Paris because they feel that is a great achievement, and also winning a stage of the Tour can change your cycling career; that's why every day, a rider sets off trying to win a stage, and that makes the racing very, very competitive."

He should know. In October last year, he graduated in international business (honours) with a specialisation in sport management at the European School of Economics. His thesis, 'The management of a professional cycling team', earned him the honour of dux of the entire course.

"I think it is good to keep all the options open," he says philosophically. "[The degree] was an interesting way of developing a new skill. When I end my racing [career], I hope I will have a choice: to stay in sport, or to start a normal life completely detached from sport. If I get a good chance, I would like to stay in cycling, or if not in cycling, in sport anyway; I've been racing since 1992 in mountain bikes, so I know quite a lot about sport."

Does being a directeur or team manager of a small team interest him?

"Not so much as a sport director, more as a team manager," he says. "It could a team manager in a small team... maybe the best option would be in a bigger team as an assistant to the team manager, so you can learn how things work at that level. I know how things work as a rider, but I have no experience as a team manager, and I think there are many things that I don't understand."

Cioni only started racing mountain bikes at 18 years of age and this year marked his sixth season on the road, but this willingness to learn, acceptance of his weaknesses and harnessing his strengths has made a success out of the now 31 year-old. It also helps having a VO2 Max (maximal rate of oxygen consumption, usually measured in ml/kg/min) close to that of Armstrong and great Spanish Tour rider Miguel Indurain. "Somewhere in the 80-90 range," he says about his naturally massive motor, although in a very matter-of-fact sort of way.

________________________

I interviewed Cioni a few days after he returned from presentation of the 2006 Giro d'Italia in Milan. With his primary focus revolving around the first Grand Tour of the year, he had plenty to say.

"I think it is a very, very difficult course, especially the last seven or eight stages - all mountain stages - so that will make the last week extremely tough," he says. "But even the first stages are not easy because we're up in Belgium, and everyone knows how hilly Belgium can be and how difficult it can be to take control of the race in the first three or four stages."

With five mountain-top finishes, Cioni calls it a climber's course, conceding that even though finishing fourth in 2004 logically means the podium next time round, a top five result would be a great finish for him. However, when I mention that Paolo Savoldelli won this year's race on what was also considered to be a climber's course, a rider similar to himself, he admits his countryman's results give him confidence to vie for the podium in 2006.

"In this Giro, it would be important to be very consistent on every mountain stage. I think it's better to lose a little time every day [in the mountains] than have a great day then have a bad day. Riding quite conservatively would be important for the final results; it's not the best course for me, but I must do my best and see what I am capable of."

However, it's not the abundance of mountains stages that's bothering Dario Cioni most. It's the final day, a cruel double stage, beginning with a sixteen kilometre uphill time trial up the Madonna del Ghisallo, followed by the traditional run-in to Milano in the afternoon. "I'm not happy about that, not at all - the only people that are happy about this are the Giro organisers and some retired riders who don't remember how hard it was racing.

"I think if you look at the last week, we don't need an extra hill climb on the last day to sort out GC; what this could mean is that you could get extremely tired riders not racing up hill but dogging along... I don't think that would be very spectacular, do you?"

Cioni exhales a big sigh. "The rider's health is such a big issue now - and I don't think this is really healthy for the riders. It's not a double-stage on the first day of the Giro - it's the last day! - and we've already been on the bike for 20 days in a row. The last rest day is ten days before, anyway, and we've already done 3,500 kilometres and who knows how many climbs before that.

"If they want to do it [a double stage], do it halfway through the Giro, not the last day. There's also a [unwritten] condition that says the last day is like a parade; they do it at the Tour - I can't see why we can't do it at the Giro. Or otherwise do the hill climb, but don't ask us to do the circuit after. The Vuelta has sometimes had a time trial on the last day, but if you look at how many riders go all out, there's probably 10 - all the other riders are looking at the time limit."

Time will be an area Cioni will be working on very seriously over the next five months. 88 kilometres against the clock - consisting of a 38 kilometre TTT on stage five, followed by a flat, 50 kilometres a week later - has prompted him to work with engineers and biomechanics, testing different frame shapes, materials and riding positions, striving for small yet significant improvements.

"That will be one of my best chances to gain some time on the climbers," he admits. "Time trialling is very strange, because you if you start working with the materials, you realise you can always improve. I want to get to the Giro with everything sorted out."