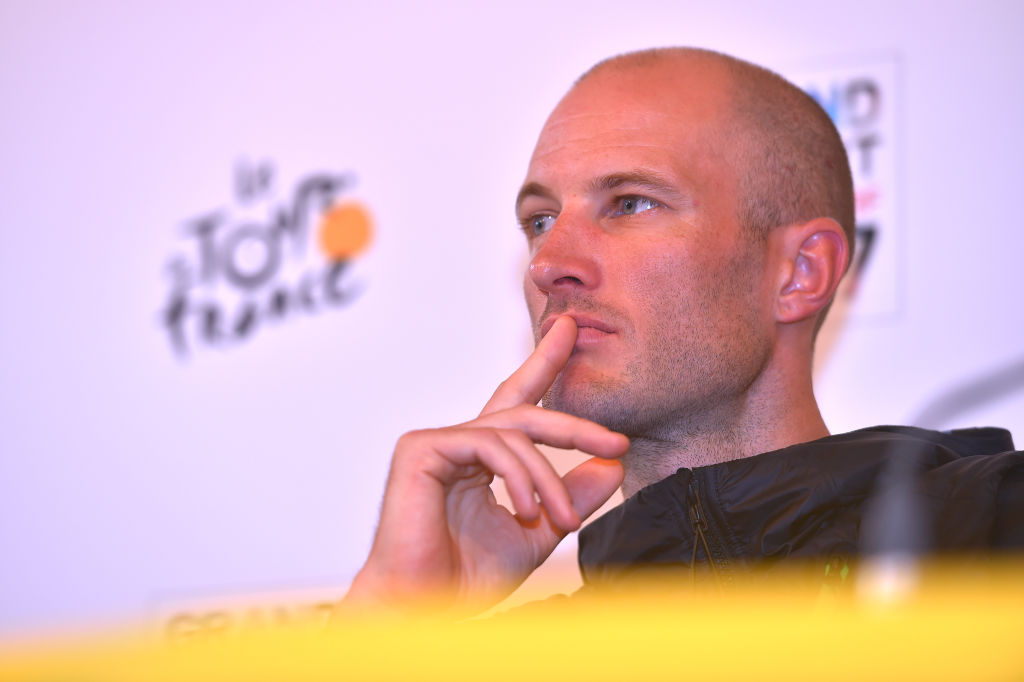

Steve Cummings: The last of the mavericks

How the British rider's unique character and breakaway skills gave him a successful but often conflicting career

Steve Cummings' retirement marks the end of an era for the 38-year-old British rider, and arguably the extinction of highly talented but maverick riders who performed best, and frequently won, when allowed to do their own thing in a breakaway.

Professional cycling has evolved massively since Cummings turned professional with Landbouwkrediet-Colnago in 2005. Power data, training plans, ranking points and corporate identities now influence racing like never before. Sprinters' teams control the flat stages and the battle for overall success has squeezed out the aggression of the baroudeur.

Lotto Soudal's Thomas De Gendt is perhaps keeping the art of the breakaway alive, and Julian Alaphilippe (Deceuninck-QuickStep) packs panache, but few teams are now willing to take a risk with a rebel or rare talent. The mavericks and the misfits have no place in an ever-more lobotomised peloton. Free-spirited riders like Cummings are facing extinction.

Cummings was never one of the bad boys of the pro peloton; he never turned up to a training camp unfit or overweight. He was always his own man, of stubborn pedigree, never scared to speak his mind and ride his own race.

His skills learned on the track meant he understood himself far better than any coach ever could. Forcing him to do things against his will most often led to conflict. He learned to accept that trait while others struggled with it.

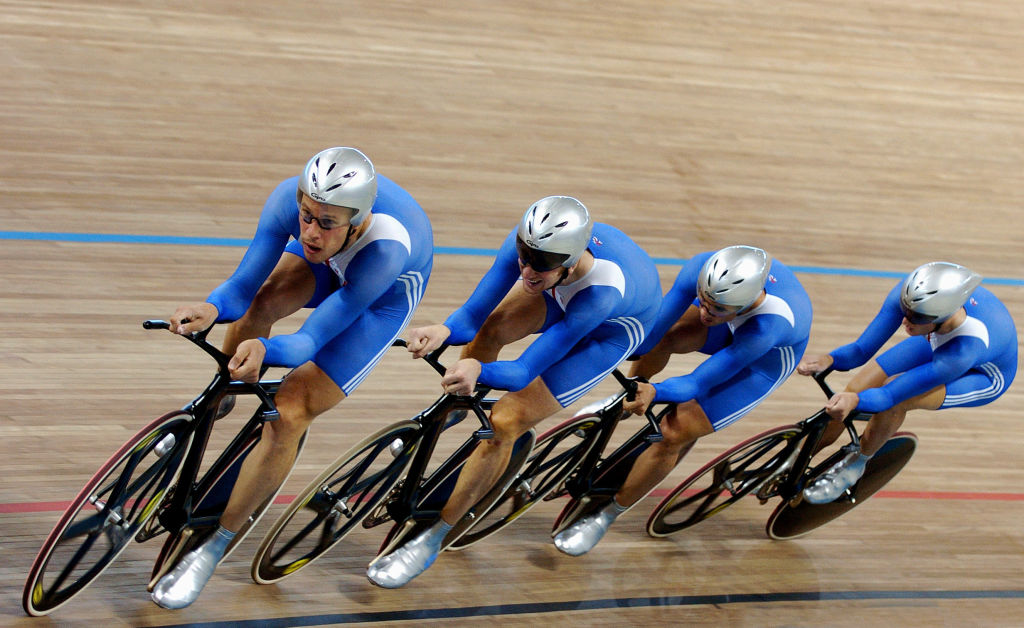

Cummings first showed his talents and character when he won the prestigious early-season Eddie Soens handicap race in 1999 as a 17-year-old junior, and he remains the only junior rider to have won it. He also won the British junior road race title in 1999, and was soon drafted into the Great Britain track squad, proving to be a talented pursuiter and winning a silver medal at the 2004 Olympics in Athens, the world title in 2005, and then gold at the 2006 Commonwealth Games in Melbourne.

Cummings became one of the anchors of the quartet, along with Bradley Wiggins, but as Britain's medal-factory became a machine, Cummings began to struggle. His muscles needed more time to recover than other riders after major track sessions, and that put him out of sync with British Cycling's regimented training and racing programmes. He could step up and perform on the big occasions, but struggled to fit the unique mould the team was casting.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

It would lead to a painful separation, but Cummings would go on to prove his worth on the road, with few regrets about not winning a haul of track medals.

After a year at the Discovery Channel team in 2007, he joined Barloworld for 2008 and 2009, with British Cycling helping to cover his wages while Barloworld offered him a solid race programme in Italy and across Europe. The Barloworld directeurs sportifs admired his talents as he made his Grand Tour debut at the 2007 Giro d'Italia, but admitted that they struggled to understand his Scouse accent and especially his preference to ride at the back of the peloton.

Alberto Volpi often ordered Cummings to move up to the front, and was furious that his orders were ignored. Cummings claimed he knew what he was doing, convinced he was safest at the back until he was needed by the team or was about to make an attack.

Things came to a head in the Italian semi-Classics in August 2008. After yet another scolding, Cummings went on the attack at the Coppa Bernocchi and won, but he put his finger to his mouth as he crossed the line in a clear message to his team.

Barloworld team manager Claudio Corti wanted to sack him for insubordination, but how could he when Cummings had just secured the team's biggest win of the season?

Keeping his free spirit alive in the WorldTour

Despite his differences with the Great Britain management, Cummings' talents secured him a place in the nascent Team Sky for 2010. He rode the Giro d'Italia and Tour de France but, as the focus turned to winning the Tour de France with Wiggins, Cummings knew he had to again move on to keep his free spirit alive.

"I want to work as hard as possible for the team and make the most of any opportunities that come my way. If I can do that, then I'm happy," he said in his subliminal message on joining BMC, perhaps not understanding the American set-up was as corporate and controlled as the team he had left.

Cummings won a stage at the 2012 Vuelta a España, outmaneuvering Simon Clarke and Cameron Meyer (both Orica-GreenEdge), as well as Team Sky’s Juan Antonio Flecha from a breakaway, but he later admitted his two seasons in the BMC red and black had felt like a straight jacket. In 2014, he also won the Tour Méditerranéen, his first stage-race victory, but the friction was increasing and he stepped down from WorldTour level in 2015 to join what was then MTN-Qhubeka, and would later become Dimension Data.

"I was getting a bit stale in the WorldTour. You see riders go there and they kind of forget how to race and they become bottle fetchers. Some guys thrive on it and others don't really get into it too much," he said at the time, clearly putting himself among the latter.

Cummings was already 33, but was still at his best, and proved on that now-famous stage to Mende at the 2015 Tour de France. It was Mandela Day and MTN-Qhubeka were in the Tour to help promote the 'Bicycles Change Lives' campaign in South Africa. Cummings stepped up and did his thing.

He got away with Thibaut Pinot and Romain Bardet. They and the French fans and television commentators were convinced it would be a day for France, but Cummings wisely paced his effort on the steep climb to the runway plateau, played off the French rivalry, and then surprised them with a late attack to win.

He took another Tour de France victory in 2016, again from a breakaway, after winning at Tirreno-Adriatico, the Vuelta al País Vasco, and the Critérium du Dauphiné. Cummings had become the most feared breakaway rider in the peloton. He also won the Tour of Britain after years of trying, confirming there was more to British cycling than just Team Sky.

That pride and sense of difference again cost Cummings a place in the Great Britain team for the Rio Olympics and, true to character, he did not hold back, highlighting a potential conflict of interest because British national coach Rod Ellingworth also worked for Team Sky.

"It’s not really a surprise when the Team Sky coach picks the team. I think the selection criteria just comes down to opinion, doesn’t it? It’s the Team Sky coach's opinion," Cummings told Cyclingnews.

However, he ended up getting a ride in Rio after all, following the withdrawal of Peter Kennaugh, and Cummings represented his country in the road race.

Denoument

The loss of Brian Smith as lead directeur sportif and then the arrival of Mark Cavendish and his entourage changed Dimension Data in 2016.

Cavendish's success at the Tour de France overshadowed Cummings' victories, but he was happy to be out of the glare of the spotlight and have the freedom to do his own thing. He signed a lucrative new contract with Dimension Data during the summer of 2017 after winning both the British time trial and road race titles, but it was the start of the end.

Cummings beat Vincenzo Nibali and Egan Bernal to win the 2017 Giro della Toscana close to his adopted home in Quarrata, west of Florence, but by then the crashes and illnesses had begun to take their toll. It was the last victory on his palmarès.

In 2018, Cummings became frustrated with the frequent changes to his race programme as Dimension Data tried to survive while Cavendish was out with the Epstein-Barr virus. He was not selected for Dimension Data's 2018 Tour de France squad, but was called up for the 2019 race just a week before the start. He lacked the form to race aggressively after fracturing his collarbone in April, only worsening his relationship with Dimension Data and limiting any chance of a new contract.

Cummings was hoping to impress other teams at the Tour of Britain but, such is the cruelty of professional cycling, he crashed out just a kilometre from his birthplace in Birkenhead, near Liverpool. His injuries included fractured vertebrae, and teams must have doubted that he'd make a full recovery at the age of 38, and so were unwilling to give him a contract for 2020.

He had hoped for a final year in the saddle but, for once, he had no control of his own destiny.

There is no chance for a final breakaway.

Stephen is one of the most experienced member of the Cyclingnews team, having reported on professional cycling since 1994. He has been Head of News at Cyclingnews since 2022, before which he held the position of European editor since 2012 and previously worked for Reuters, Shift Active Media, and CyclingWeekly, among other publications.