Sombre signings, peloton politics and stretches of illness – here's one neo-pro's opinion of the surprises of the WorldTour

Neo-pro graduate Anders Foldager explores what he's learned about his own pre-conceptions, how his body and mind adapted, fitting in and winning his first pro race

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When a new pro joins the WorldTour, the dial goes back to zero in their career. Achievements in junior or under-23 ranks quickly pale in comparison.

Many may dream of competing with Tadej Pogačar and Mathieu van der Poel right away, but reality rarely matches those lofty aspirations.

The fairytale promotion comes with plenty of difficulties and daunting changes.

The level of racing soars, racing tactics become more complex and leadership opportunities tend to be scarcer. Then, there is illness or over-training lurking around the corner, given the burning desire to show their worth and a new peloton to fit into. Being a pro cyclist is not just riding a bike very fast; it’s also winning friends and influencing people.

With an eventful 2024 full of highs and lows behind him, talented 23-year-old Anders Foldager (Jayco-AlUla) delves into what it’s really like for a first-year pro in the WorldTour.

No champagne at the contract signing

Foldager’s arrival in the sport’s top tier was far from sudden. Already earmarked as a talent by the Australian team in the autumn of 2022, team performance director Marco Pinotti spotted his strong under-23 Giro d’Italia stage results and they met in the Italian’s home city of Osio Sotto to discuss the team and whether they could use him.

Soon afterwards, Pinotti called and said they wanted to sign him as a pro in 2024. The Dane left the contract's ins and outs to his manager.

“It’s not like you see on TV where they meet the team manager, sign the contract and have a glass of champagne,” Foldager says. “Sitting alone in an apartment in Italy, you just receive an e-mail, you sign it online, then you’re waiting for the other party to sign it as well.

“So, it was actually a bit of an anti-climax. But of course, I was over the moon, so happy because from that day I knew I would be professional. I called my family immediately and told them that it had succeeded.”

Sign up to the Musette - our subscriber-only newsletter

He agreed terms and signed on as stagiaire that winter. The following year, racing for the Italian Continental team Biesse-Carrera, the Danish puncheur won a stage in the Tour de l’Avenir and Giro Next Gen, a sign of his potential. However, his deal remained secret. “It was nine months from that moment [signing the contract] until it was out in the open, or something like that, so I couldn’t really tell anyone apart from my family and closest friends,” he says.

However, doing seven pro races in 2022 and joining their December training camp meant that by the time his first camp as a full-time Jayco AlUla rider rolled around, the squad felt familiar. “I’d been racing and training with them and working with the coach and doctor. It didn’t feel strange to come in,” he says. “Plus this team is always fun, no matter who you’re with.”

A perk of neo-pro life was being inundated by team kit. “Opening that box of clothing with all the new stuff was like a second Christmas Day. Also, considering I was coming from UCI Continental level where you get maybe two jerseys and two bib-shorts,” Foldager says.

It went beyond apparel to taking ownership of several different Giant bicycles too. “Here [at Jayco-AlUla], it is one training bike and one TT training bike, then three bikes for racing, one to race on and one for each team car. I’d never had a bike only meant for training before, so that was also something new.”

Matching expectations to reality

Over-training can regularly be an issue for neo-pros adapting to longer races, more travel days and heavier racing schedules. EF Education-EasyPost neo-pro Jack Rootkin-Gray found that out the hard way. “I came into the year really keen for it, maybe it’s your classic storyline of ‘not going as well as you want, need to train harder.’ That self-deprecating cycle,” he told Cyclingnews late last year. “You can f*** yourself quite easily doing too much. Taking it easy is probably the main bit of advice … less is more.”

However, getting any training done at all was the problem for Foldager. “I was sick virtually from October 2023 to March 2024, on and off, with different stuff. My immune system wasn’t strong enough to handle anything,” he says. “That was really stressful: I was about to live my dream but I couldn’t train, I couldn’t do anything.

“Just sit there, lie in my bed, do the antibiotic treatments, go to the hospital and the doctor. Every time I thought I was in the clear and started training again, I got something new and was back to zero.

“The whole team, the doctors and my coach, Joshua Hunt, kept me really motivated to take it nice and slow, doing a short build-up phase before I could race again,” Foldager says.

“I think it takes some pressure off a young guy like me. Even if you don’t live 100% up to expectations, they don’t rip your head off, so you can go into your work more relaxed. That also makes you do better work in the end. And sometimes your own expectations are a lot higher than the pressure put on from the outside. It’s important to have someone to keep you on track so you don’t rush things through.”

Springtime surprises

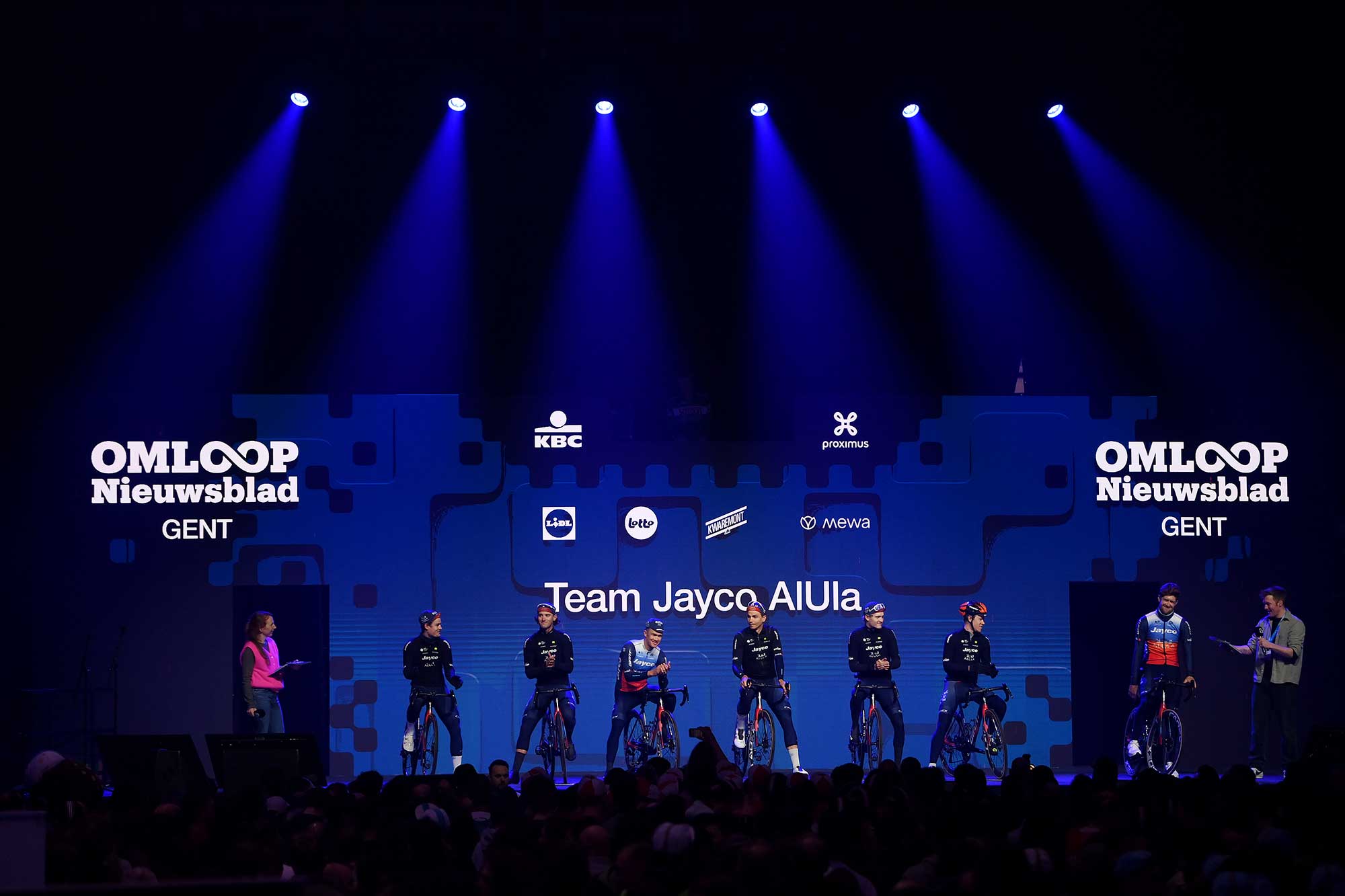

His debut came in February at Omloop Het Nieuwsblad where he returned to the team bus inside the opening 90 minutes of racing. After riding Settimana Coppi e Bartali for training, his season went from 0 to 100 in mid-April when he was called up to Paris-Roubaix, several days before the race.

“I think someone got sick so they needed a rider. That was a huge experience. Maybe I was more mentally ready than I was physically. I got through but out of the time limit. I count it as a finish,” Foldager says. “Also to get the opportunity from the team, even as a reserve, was nice. I also did all the Ardennes races: maybe I was not ready to do any results, but for the next years, at least I’ve tried them.”

Stepping up to the sport’s big leagues also means a transformation in technical skills and riding ability. Previously a “big fish in a small pool”, the Dane found himself in an ocean of hitters. “I think what surprised me the most in my neo-pro year was the base level in the WorldTour,” Foldager says. “When you’re coming from the under-23 level, if you’re one of the strongest guys there and open up on a five or 10-minute climb, there are probably 15 riders left in the group.

“But in the WorldTour peloton, for example at the Tour de Suisse, everyone is still there. I remember the first time I had to swallow that feeling of looking over my shoulder after a hard climb and seeing all the other riders on the wheels. Thought you made the group? Everyone made the group. Here, everyone knows how to ride their bikes.”

While Foldager said he didn’t have to do a neo-pro initiation – a tradition in some teams, usually involving downing alcoholic drinks or wearing fancy dress – the existence of this widespread custom underlines a stark truth: starting as a neo-pro means that (unless you’re a super-talent like Isaac del Toro), you are the bottom of the pecking order in the team and the bunch.

“There is a hierarchy and that’s how it should be,” Foldager says. “If Pogačar or Jonas Vingegaard come next to me, I probably don’t push them away. I don’t fear them, but I have respect for them and what they can do - you’ve got to have respect for those guys and the palmarès they’ve got. But I don’t give them a place in the final if I have to be there myself.

“Knowing people in the bunch matters. People who have been in the peloton for a long time have their friends, but they’ve also got their enemies,” he adds. “Some guys maybe have more enemies than friends and it’s just more difficult for them to move around. And if you have more experience, have been in more teams and are friends with a good bunch and you’re likeable, it’s easier to go around. You don’t win races by being nice, but you can also lose races if you’re a dick all the time.”

'If it's under-23 or a WorldTour race, the winning feeling doesn’t change'

Foldager had not expected to win in his first season, especially after his chequered winter. But he got that monkey off his back in the summer, with back-to-back pro wins at June’s 2.1-rated Tour of Slovakia in the race-opening TTT and second stage.

“When you win as a team, it’s so much better, everyone was so happy. Pinotti, our performance man, made all the plans and it worked out perfectly,” he says. “Then the next day, I knew it was a good finish for me, so I put my hand up for it. It was basically an uphill bunch sprint on a little 500-metre climb.

“If it’s under-23 or a WorldTour race, the winning feeling doesn’t change. Crossing the line first gives the same sensations from when you’re 12 years old and won your first race. It’s just more attention now. That took off some pressure for the rest of the season.”

Having picked up some fetching Maap-sponsored apparel for the new year, Foldager finds himself familiar with everyone and at home at Jayco-Alula, with plenty of lessons learned. The second-year pro will hope for his own purple patch in the Australian squad’s eye-catching new kit.

“So far, going into 2025, I’ve had the perfect winter but it’s not over yet,” he says. “My level now is way higher than January last year. We’ll see how many chances I’ll have to race for my own results [this season] or how much I’ll have to go [work] for some of the other guys, but I hope to do some good results at the start of the season.”

Last but not least, it’s not all been an on-the-bike education. His English has come on leaps and bounds, even if he is still some way from going around calling everyone “mate”. “If I’ve been at a race with seven Australians, maybe sometimes I pick up the accent a bit, but I still speak it with a Danish accent,” Foldager says, laughing.

If you subscribe to Cyclingnews, you should sign up for our new subscriber-only newsletter. From exclusive interviews and tech galleries to race analysis and in-depth features, the Musette means you'll never miss out on member-exclusive content. Sign up now

Formerly the editor of Rouleur magazine, Andy McGrath is a freelance journalist and the author of God Is Dead: The Rise and Fall of Frank Vandenbroucke, Cycling’s Great Wasted Talent and Tadej Pogačar: Unstoppable.