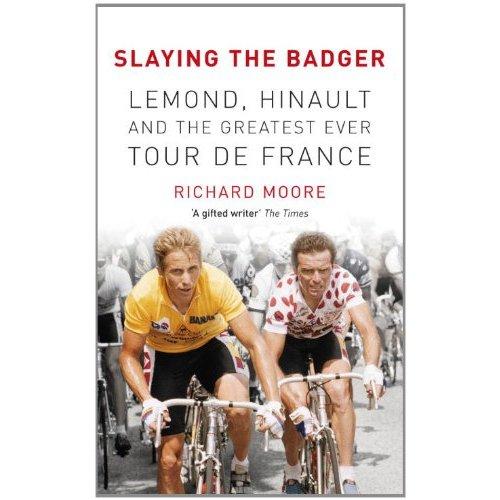

"Slaying the Badger" recalls 1986 Tour de France

Exclusive excerpt from Richard Moore's book on LeMond/Hinault battle

Richard Moore, author and Cyclingnews contributor, brings us an exclusive excerpt from his latest book, "Slaying the Badger", released on May 26, 2011 on Yellow Jersey press. Below he gives an explanation of why he set out to chronicle the 1986 Tour de France duel between Greg LeMond and Bernard Hinault.

In "Slaying the Badger" - a title that has already generated reaction ranging from amusement to bemusement - I wanted to tell the story of the 1986 Tour de France, which I contend is "the greatest ever."

That claim has provoked plenty of reaction, too. Some vehemently disagree. But most concede that it was certainly great and unusual and even more full of intrigue than most Tours; and nobody can deny that it was historic, with Greg LeMond 'slaying the badger' (Bernard Hinault) to claim a first English-speaking victory.

So, I wanted to tell - and re-live - the story of that Tour, and the astonishing, intra-team duel between LeMond and Hinault. At the heart of it is the relationship between these two riders, with so much spice added by their very different personalities. LeMond and Hinault could not be less alike: Hinault was gruff, aggressive, and raced with a snarl; LeMond was boyish, friendly and slightly vulnerable. It made their rivalry ripe for the kind of contest we witnessed in 1986.

Both Hinault and LeMond are worthy subjects for biographies, and Slaying the Badger is, as well as the story of the 1986 Tour, a kind-of biography of both. I was keen to assess their respective legacies - and to re-visit them in a literal sense, which meant going to interview them at their homes, Hinault in Brittany, LeMond in Minnesota.

The following extract, from early in the book, describes my meeting with LeMond and his wife, Kathy (her contribution was invaluable given that she and LeMond were such a close team from the moment they arrived in Europe in 1981, when the 19-year-old LeMond signed for Hinault's Renault team).

Hinault, his Renault directeur sportif Cyrille Guimard and L'Equipe journalist Jean-Marie Leblanc had been to America over the winter to talk to LeMond about joining the Renault team. Hinault had told me the plan was for him and LeMond - already tipped for greatness - to, as he explained, "compete on different fronts... One would win the Giro, another would win the Vuelta. Then we'd come together, to give us two options at the Tour. Voila!"

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

-----

"He doesn't remember it?' yells Greg LeMond, leaning forward until his chest bounces off his kitchen table. "Holy shit!"

LeMond, silver-haired, chunky, almost barrel-chested, but with the same sparkling pale blue eyes, has just been told that Bernard Hinault, upon being asked about his visit in November 1980 to the United States, where he, Cyrille Guimard and Jean-Marie Leblanc stayed in the LeMonds' house, seems to barely remember it.

"That's so funny," chips in LeMond's wife, Kathy.

"I've got photos of it," adds LeMond. "I was looking through them about two months ago; Hinault dressed as a cowboy."

"You do?' says Kathy. "That's cute!"

"Hinault's the first guy who shot me," continues LeMond, almost nostalgically. "Right in the eye. We were shooting…I grew up hunting quail, so I took them out quail hunting. And Hinault shot me." Then he adds quickly, "By accident."

Since LeMond had already signed a contract worth $18,000 a year with the Renault team, the Stateside trip was essentially a PR exercise, though it also allowed Guimard, as he told me, to see LeMond in his own environment, and get to know him better. "I just felt good about Guimard," says LeMond, explaining his decision to join his team. "I didn't speak French, though I took some in high school, but Guimard [contrary to what he now claims] made a big attempt to speak English."

Kathy nods her head, adding: "Guimard started English lessons when Greg joined the team. A tutor came to his house every week. And every day, even at training camp, he studied English. I thought that was amazing. He was extraordinary to us. I really think that with Greg he went so far beyond the call of duty – I mean, Greg was a neo-pro. I think he really, truly saw that Greg was going to be his next star…"

"Nooooo, I don't think," LeMond interrupts. "Honey, he––"

"He did things for you he didn't do for your peers."

"I remember being told," adds LeMond, switching tack again, "when I signed that contract: 'Don't tell anybody how much you're getting, because you're the highest paid neo-pro ever'…Then later, of course, you find out everybody's been told that."

LeMond laughs, but it's clear that Guimard did go to extraordinary lengths to, as he puts it, 'integrate' the LeMonds. In this respect he was more enlightened than many others; he understood that in order for LeMond to succeed – and for him and Renault to get a return on their investment – he would have to do more than simply "transport them from one country to another."

-----

Though LeMond, talented, ambitious and already successful, knew that Europe, with its "proper racing…proper competition" was "where I wanted to be', he already felt some pangs of homesickness. That was to be a constant battle, and something Guimard was alert to, hence his efforts to learn English, and to help with the LeMonds 'integration' into French life. And Guimard took another step – he signed Jonathan Boyer, the only other American in the European peloton, six years older than LeMond, who'd lived and raced, with modest success, in France since 1973.

But for LeMond moving to Europe was a massive step, a huge sacrifice; as it was, too, for Kathy, who, after their marriage on 21 December, moved with him. Apart from leaving home, there was also the fact that LeMond – intelligent, articulate – was gambling everything on cycling, giving up on the idea of going to university. "Giving up on our education," says Kathy now, "that was a big thing."

"That's what we thought," points out LeMond, "but that's not what most cyclists think. They're not thinking of going to college."

Arriving in Europe on 9 January 1981, the LeMonds picked up the car they'd been promised. Since his new team was a car manufacturer they would have been justified in expecting a reasonable motor – instead, they received the keys to a car with, bizarrely, a warped windscreen, seriously affecting visibility. "It was a dud," says LeMond.

Nevertheless, they drove out of Paris and headed west to Brittany. Guimard had wanted the LeMonds to live near him, close to Nantes, and arranged a house in La Chapelle-sur-Erdre, which, he promised, would be fully furnished. But as with the car, they were to be disappointed.

What they found in La Chapelle-sur-Erdre was a shell: a cold house with no furniture, nothing. The couple spent two weeks in a hotel – "it rained every day," says Kathy – before LeMond headed to the south of France for a month-long training camp. Meanwhile, Kathy temporarily moved into another, furnished house, arranged by Guimard – still trying his best to help the LeMonds settle into French life, but clearly with some difficulty – "with a mattress and a cooking pan". As for the furniture, "they kept saying, 'it'll be here next next week,'" says Kathy, "but it was the middle of April when we finally got furniture."

At the training camp, meanwhile, LeMond struggled, because he was seriously overweight. Over the winter he had followed the advice of Belgian cycling friends who "told me to take six months off and just have fun, because once you turn pro you'll never take six months off again until you're done," says LeMond. "I literally did that, and put on about ten pounds. When I showed up for the early season I was so out of shape. Guimard had me do a 110-mile race, then ride another fifty miles afterwards. After six weeks of that I was very skinny."

Guimard's programme worked. By April LeMond was going well – well enough to play a strong team role at Paris–Roubaix, which Hinault won. And in May he registered his first win, a triumph vividly recalled by Phil Anderson – not so much for the win, but for the victory celebration. It came in a stage of the Tour de l'Oise, north of Paris. "We were in a break," says Anderson, "there were about ten of us, and, coming round the last corner, Greg just kicked everyone's arse. I got second, but all I remember is Greg, as he crossed the line, yelling out: "Yeeeeeeeeeehaaaaaaaaaa!" He had his arms above his head, and he just let out this yell. It was so American – he sounded like a cowboy or something. But I'd never heard or seen anything like it. That's not what you did at bike races, you know?"

LeMond soon had even more cause to be delighted when Guimard rewarded his protégé's strong performances with a surprising but significant mid-season wage-increase, upping his pay to around $25,000.

The racing was one thing – LeMond coped admirably with that, his monstrous talent ensuring that he wasn't out his depth as so many neo-pros are (the average professional career is said to be around three years). But living in France was another matter. Here there were little cultural hurdles to overcome; gaps that LeMond seemed unable, or unwilling, to bridge.

Eating proved a challenge. Not so much the food – though that, too, was testing, and LeMond sought out his favourite Mexican food when he could, which in the early 1980s was with great difficulty– but more the French dining experience. Nothing, LeMond discovered, would be allowed to interrupt lunch or dinner. Even long journeys between races would routinely be broken, he soon found out, by a lengthy stop for lunch. LeMond, as he told American journalist Samuel Abt at the time, found the ritual intensely frustrating. "I thought, let's just get there! Then we'll have lunch!"

Adding further to his irritation was the time spent dining – often at least two hours. Unable at first to speak the language – though LeMond did become fluent, and would happily give interviews in French later in his career – he found those two-hour lunch breaks with his new teammates to be torture. To alleviate his boredom, LeMond began taking a book to dinner and reading at the table – a heinous crime in France. "Some dinners were so slow, so long," says LeMond now, "and I was bored. I always liked to read something, anyway. In my first four weeks with the [Renault] team I read about twelve Robert Ludlum books." Naturally, his teammates – the Francophile Boyer especially – were horrified.

LeMond was aware, of course, that his path would be smoother if he at least gave the impression of adapting and fitting in – which might explain a photograph in a 1981 edition of Miroir du Cyclisme. It depicts him in central Paris wearing a beret, nursing a glass of vin rouge, with a baguette and French newspaper tucked under his arm. But it was about as convincing as Hinault's cowboy schtick for L'Equipe the previous year. The truth was that while many others, Boyer, Stephen Roche, even the maverick Robert Millar, went to some lengths to fit in – marrying French girls in the case of Roche and Millar – LeMond made few concessions.

Arguably this highlights a paradoxical aspect of LeMond's personality. For all that he was almost universally liked and lauded for his friendliness and openness, LeMond could also be stubbornly independent, even rebellious. There is, as an example, a story from later in his career that constitutes an even more serious breach of French dining etiquette. Finding the restaurant too hot one evening, LeMond is said to have responded by removing his shirt.

I had to ask him: is this true? LeMond looks startled – not at the allegation, but that I should even doubt it. "Oh yeah. Oh yeah, it's true. The French riders were all shocked, but I think I was right to do it because your core temperature goes up. We'd be sitting in these ovens. I was like, I can't handle it. You gotta get the heat away from you.

"I loved the heat when I was racing, but I grew up in Nevada, where it's hot during the day, but it drops at night, and gets really cool. When it's hot, I can't sleep. Even today, I need it below twenty degrees.

"The best story," LeMond continues, eyes sparkling at the memory, "was when we were staying north of Arles, in the Provence area, in a Club Med-like hotel resort. It was, like, 110 degrees, and this was when there was no air conditioning, nothing. And we had the shittiest rooms. And…it was so hot.

"The other riders are fine. They're sleeping. But I can't sleep, so I drag the mattress out, next building's 100 metres this way, and there are other buildings 150 metres the other way, and there's dirt and grass – not grass, but that Provence dirt/grass sort of stuff – and I pull this mattress out there. And I sleep naked. With a sheet, and two pillows – one for my head, one between my legs. I always slept with a pillow between my legs. Anyway, I'm out there and…I wake up. And there are people walking right past me – families! I'm waking up, it's seven thirty, eight o'clock, a crystal clear morning, warm and hot, and I'm lying there, butt naked."

Slaying the Badger by Richard Moore (Yellow Jersey) is available now. Twitter: rbmoore73.