Six of the best: Through the years at Gent-Wevelgem

Looking back at classic editions of the race, from Maertens to Paolini

The Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic has seen the entire Spring Classics calendar postponed, but in the absence of 2020's racing, we at least have a wealth of history to look back on to get us through the empty Sundays.

This Sunday was set to see the 82nd running of Gent-Wevelgem, one of the key Flanders Classics in the run-up to the big one, the Tour of Flanders. We've taken a look back at some of the most compelling editions of the race from the last half century.

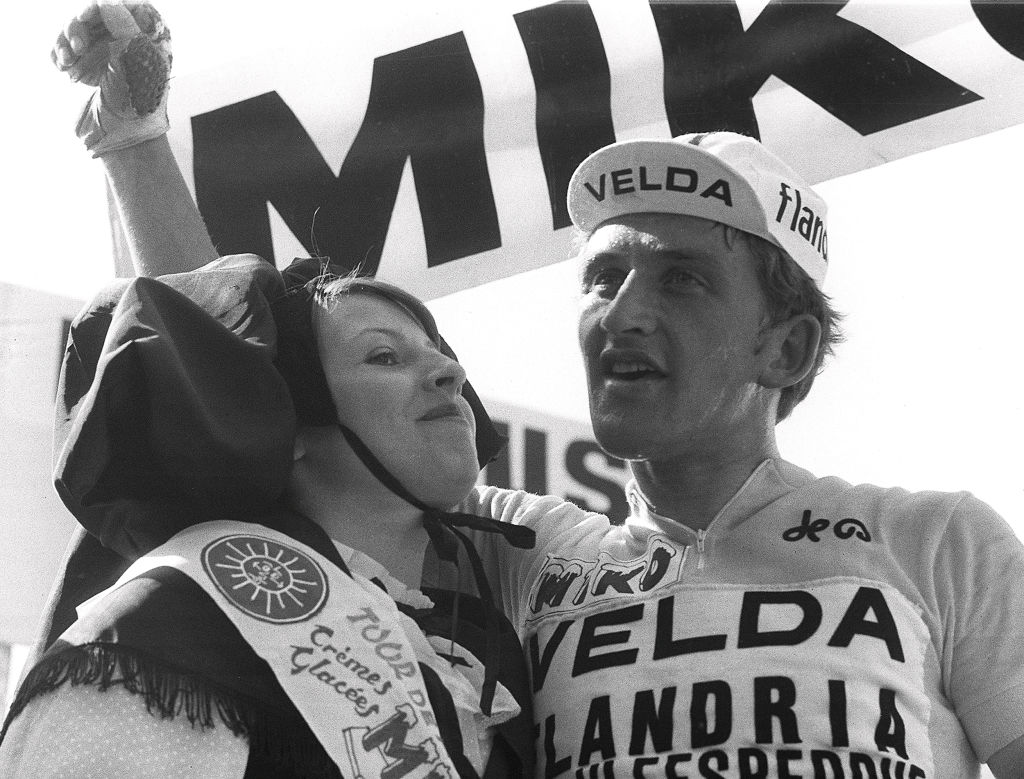

1976: Maertens, snow and internal politics

With Eddy Merckx's career winding towards a close, some in Belgium heralded Freddy Maertens as the Second Coming, but, in truth, the boy from the plat pays near the North Sea coast was one of a kind. Like the Brazilian Ronaldo in football or Jonah Lomu in rugby, he seemed to embody a whole new paradigm of bike rider, all strength and sinew as he crushed the recently-released 12-tooth sprocket with striking ease.

The two-time world champion never won a Monument – though the rather modern term didn't carry the same cachet during his career – but he did amass a glut of classics and semi-classics in a dizzying spell in the mid-1970s, when it seemed there were no limits on what he could achieve.

Maertens' signature win in a Belgian classic came in the 1976 Gent-Wevelgem, which was fought out in frigid, snowy conditions on the road and against a backdrop of heated internal debate on his Flandria team, where newly installed manager Lomme Driessens and the demoted Briek Schotte were grappling for power.

Three days earlier, Maertens had frittered away his chance at the Ronde after he and Roger De Vlaeminck had allowed the winning move ghost clear while they eyed one another on the run-in to Meerbeke. That result did little to heal the internal schism, with Schotte bluntly telling Sport 70 magazine afterwards that Maertens had raced "like a caveman."

Gent-Wevelgem offered an immediate chance for redemption. Twelve months earlier, Maertens had won the race in relatively routine fashion from a reduced bunch sprint. This time out, Maertens wanted not only to win, but to conquer. On a snow-banked Kemmelberg, he duly piled on the pressure, stringing out the leading group and then forging clear alone once the treacherous descent had been navigated.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Despite riding into a block headwind, he battled to fend off a chase group that included Merckx, De Vlaeminck and Francesco Moser. "However, I could only stay in front of the group of pursuers for 15 kilometres, so it was only in the sprint that I was able to finish the job off," Maertens wrote in Fall From Grace, arguably the most entertaining autobiography ever written by one of the sport's champions.

In keeping with the overall tone of a book that sometimes reads as though it could have been ghosted by Larry David, Maertens' laconic, almost underwhelmed account of his Gent-Wevelgem victory is incidental to his retelling of the airing of grievances among Flandria's management that spring, with Driessens theatrically announcing his retirement after the race only to retract the statement half an hour later. "He only wanted to put [Flandria owner] Paul Claeys under pressure finally to remove Briek Schotte from the scene," Maertens wrote.

1977: Hinault lays down a marker

Bernard Hinault's place in the pantheon owes much to his unrivalled strike rate in the Grand Tours – 10 wins from 13 starts, two second place finishes, and one abandon (while wearing the maillot jaune at the 1980 Tour de France) – but it would be remiss to overlook his one-day record. Although Hinault didn't come close to amassing a Classics palmarès to match that of Merckx, it is striking how many of the keynote successes of his career came in one-day races. In that discipline, Hinault was, like Mark Hughes, not so much a great goal scorer as a scorer of great goals.

Before the snowbound win at the 1980 Liège-Bastogne-Liège, the exhibition at the Sallanches Worlds and the almost dismissive triumph at Paris-Roubaix in 1981, Hinault gave a hint of what was to follow at the 1977 Gent-Wevelgem. The race that year was held in late April, on the Wednesday before Liège-Bastogne-Liège, and was the longest ever edition, at 277km.

It was almost arguably the most difficult parcours in the race's history, with the route deviating into the Flemish Ardennes for eleven climbs, including the Koppenberg – labelled as the Steengat in the road book – before heading north towards Gent-Wevelgem's heartland of the Heuvelland and a double ascent of the Kemmelberg.

Hinault's build-up to the race hardly inspired confidence in his bona fides as a would-be Flandrien. Two weeks previously, he had incurred the wrath of Renault directeur sportif Cyrille Guimard with a rather fleeting appearance at a chilly Tour of Flanders, abandoning after 200 metres and promptly driving home to Brittany in his cycling kit.

As William Fotheringham recalls in Bernard Hinault and the Fall and Rise of French Cycling, Guimard was sufficiently irked to send Hinault a formal warning by registered mail, but the falling-out was temporary. Hinault was back in the fold in time for Gent-Wevelgem and though the Renault mechanics had equipped his bike with gears suited to Paris-Roubaix rather than the bergs of the Flemish Ardennes, he made light work of the impediment.

A reduced leading group clattered off the second ascent of the Kemmelberg to contest the finish and Hinault could sense the fatigue around him. As the race approached Menen, he attacked viciously. His companions gave chase, but having stung their legs, Hinault now crushed their spirits by kicking even harder just as they were on the cusp of pegging him back. The final 20km were an exhibition, as he soloed to his first major international victory, 1:24 clear of Vittorio Algeri. Four days later, Hinault's Belgian campaign concluded with another conquest, this time at Liège-Bastogne-Liège. He was on his way.

1988: Kelly salvages Classics campaign in rare appearance

A strongman with a rapid sprint, Sean Kelly was the perfect prototype of a Gent-Wevelgem winner, but the Irishman was sometimes a victim of his own versatility. In the mid-1980s, the race was more firmly established in its traditional slot on the Wednesday between the Tour of Flanders and Paris-Roubaix, but Kelly, on the instructions of manager Jean de Gribaldy and, later, at the behest of sponsor Kas, tended to be otherwise engaged.

Each April from 1984 to 1988, Kelly travelled directly from the Tour of Flanders to the Tour of the Basque Country and then returned back north just in time to line out at Paris-Roubaix. It was an almost absurdly punishing schedule, but a remarkably successful one for Kelly. Both of his Roubaix victories (1984 and 1986) came in that period, even though he was hardly sparing himself in the Basque Country, where he won the overall title in 1984, 1986 and 1987.

In 1988, however, the calendar clash was temporarily resolved when Gent-Wevelgem was shifted to April 20, three days after Liège-Bastogne-Liège. Having failed to land a Classic during an ill-starred 1987 campaign encapsulated by his snapped handlebars at Paris-Roubaix, Kelly risked drawing a blank once again in 1988, but he was rarely more dangerous than when drawing up a stool at the last-chance saloon, as his hat-trick of Tour of Lombardy wins testified.

It was, by any measure, a busy week for Kelly, who lined up at Gent-Wevelgem just three days before flying to Tenerife for the Vuelta a España and 48 hours before news broke of his positive test for codeine at the Tour of the Basque Country. That year's Gent-Wevelgem, meanwhile, almost matched 1977 in length, but this played to Kelly's qualities of endurance. He was part of a five-man group that forged clear on the ever-pivotal Kemmelberg in the company of Claude Criquielion, Gianni Bugno, Ron Kiefel and Ludo Peeters, and, not for the first time, he was able to count on a willing accomplice among their number.

Kelly and Criquielion had struck up a firm friendship when they had been teammates at Splendor in the early 1980s and though their paths had separated since, their old alliance remained resolutely intact. A year earlier, Kelly had rebuffed all entreaties to help peg back Claude Criquielion's winning move at the Tour of Flanders, and the debt was repaid on the run-in to Wevelgem, where the Hitachi rider – a notedly sluggish sprinter – had helped to dissuade attacks in the finale by keeping a high, even pace at the front on the approach to the finish.

"He rode all the time in the group, and he wound up the sprint which was the best thing for me," Kelly said at the finish, not even bothering to mask their cross-party collaboration. "He did a good job for me so hopefully I can return it to him one day."

In the five-man sprint that ensued, there could only be one winner, even if Kelly cast cautious glances over his shoulder at Bugno, who was planted on his rear wheel in the final kilometre. The Italian stayed there, however, even after Kelly swept past Kiefel in the final 100 metres to bridge a two-year gap to his last Classic victory. "Riders have won Classics at 33, 34 years of age, so it's never too late," said Kelly, who had little time to savour the win. Three weeks later, he rode into Madrid in the maillot amarillo of Vuelta winner.

1992: Cipollini-Abdoujaparov II

Bunch sprinting has always been a fraught business, but the occupational hazards never felt more obvious than in the 1990s, when the finishing straights of Europe were prowled by the man dubbed as the 'Tashkent Terror.' In truth, the risks taken by Djamolidine Abdoujaparov weren't much more extreme than those of his rivals, but sprinting's jungle has always tended to make pantomime villains of outsiders and new arrivals. Abdoujaparov, born to a Crimean Tatar family in Uzbekistan, had travelled further than most.

After a subdued debut season with Alfa Lum in 1990, Abdoujaparov caught fire when he moved to Carrera the following year. His two stage wins, the green jersey and a spectacular Champs-Élysées crash at the Tour de France were the culmination of that campaign, but his first calling card was delivered at Gent-Wevelgem, where he conjured up a powerful sprint to claim the honours ahead of Mario Cipollini.

Cipollini had arrived in Belgium with a burgeoning reputation as a fastman but he was balked by Abdoujaparov, who veered across on Menenstraat to cut him off in the final 50 metres. Cipollini lamented afterwards that he would have to start getting his retaliation in first. "I was forced to slow when Abdoujaparov went. I'm too naive, but I have to put up with some real bandits. Vanderaerden elbowed me in the side," he complained. "I'll have to learn to be nasty."

Twelve months later, having swapped Del Tongo for the new Italo-Belgian GB-MG outfit, Cipollini was as good as his word. Gent-Wevelgem again came down to a mass finish, and this time, the roles were reversed. Cipollini hit the front after opening his sprint in the centre of the road and then deviated dramatically to his left in a bid to shut out Abdoujaparov.

The Uzbek, however, wasn't prepared to yield to such intimidation. At 60kph, he simply reached out and tugged Cipollini's jersey, slinging himself past the Italian and across the line in first place. A vexed Cipollini, meanwhile, raised his arms in celebration anyway, convinced that the commissaires would declassify Abdoujaparov.

They did, but only after Abdoujaparov had been feted on the podium and GB-MG manager Roger De Vlaeminck had launched a formal objection on Cipollini's behalf. "I wanted to win in a nicer way, you know, when everybody sprints straight," Abdoujaparov said before learning of his disqualification.

Cipollini, for his part, was fortunate in the extreme not to be disqualified for his own manoeuvre. A contemporary race jury would surely award the win to Johan Capiot, the third man across the line. In 1992, Abdoujaparov, the Mike Tyson of sprinting, paid for his reputation, while Cipollini escaped unpunished to take home the prize.

"There was a slight deviation from Cipollini towards Abdoujaparov, but without putting him into the barriers or preventing him from coming past," said head commissaire J. Madeleine. "Then Abdoujaparov committed a serious infraction by pulling Cipollini back."

In 1993, Cipollini-Abdoujaporov III proved a relatively tame rematch. The Italian took the honours, while Abdoujaparov had to settle for third. Second place, incidentally, fell to Vanderaerden. "This is my most beautiful, most decisive and cleanest win," Cipollini said.

1998: Vandenbroucke gets his way

Mapei had an embarrassment of riches in the 1990s, which allowed Patrick Lefevere the luxury of leaving some lofty names out of his line-up for the cobbled Classics.

In the spring of 1998, Frank Vandenbroucke had ambitions of testing himself on the pavé, but with men like Johan Museeuw, Franco Ballerini and Andrea Tafi already at his disposal, Lefevere preferred to divert the youngster's attention to the hillier terrain of the Ardennes.

After winning Paris-Nice, Vandenbroucke had lined up among the favourites for Milan-San Remo only for a crash at the foot of the Cipressa to bring an untimely end to his challenge. The 23-year-old was then scheduled to build towards Liège-Bastogne-Liège by riding the Tour of the Basque Country but, perhaps smarting from that Primavera disappointment, he cajoled Lefevere into fielding him at Gent-Wevelgem.

Friend and training partner Nico Mattan, a resident of St Eloois-Winkel on the race route, was included in the VDB package. "Frank and I were actually supposed to ride the Tour of the Basque Country that year," Mattan told Sporza in 2018. "I still remember when Frank went to Patrick Lefevere and said: 'That's not possible. Nico and I have to participate in Gent-Wevelgem on Wednesday.'"

Mapei had already won the Tour of Flanders through Museeuw and would go on to fill the podium at Paris-Roubaix, where Ballerini took his second win. At Gent-Wevelgem, the strategy was built around teeing up Tom Steels for a reduced bunch sprint, but that plan had to be hastily withdrawn when he lost contact with a front group that still included men like Cipollini.

Rather than controlling the race, Mapei now sought to blow it apart. Vandenbroucke made his first attempt to go clear ahead of the Kemmealberg but Saeco's red guard brought the race together over the other side.

On the run-in, Mattan tested their resolve by attacking near Vandenbroucke's native Ploegsteert, with 25km to go. When Lars Michaelsen bridged across 10km later, Vandenbroucke was tucked smartly on his wheel.

Michaelsen, winner of Gent-Wevelgem in 1995, was the quickest of the trio by reputation, and so the Mapei pair took it in turns to attack him on the approach to Wevelgem.

"Frank actually wanted me to win, but I had cramps in the last 2 kilometres," said Mattan, whose own day would come in the contentious finale of 2005. Beneath the red kite, Vandenbroucke delivered the telling blow, accelerating crisply clear to take the honours, while Mattan crossed the line in third place, arms aloft. "I gave the finale a bit of colour," Mattan said.

2015: Paolini the last man standing

Gent-Wevelgem moved from its midweek date to its current weekend slot in 2010, but for the opening years of the new calendar, it often felt overshadowed by some spectacular editions of E3 Harelbeke, which had so successfully positioned itself as the dress rehearsal of choice for the Tour of Flanders.

In 2015, however, Gent-Wevelgem provided the most compelling day of racing of the entire spring, even if one wonders whether the event should have been allowed to go ahead at all given the harshness of the conditions. Certainly, had the UCI Extreme Weather Protocol been enacted 12 months earlier, the commissaires would have had food for thought, but instead, the race continued as normal – or at least as normally as the high winds permitted.

The first indication that this would be no ordinary day came after 70km, when the peloton reached the flat, exposed plain of the Moeren, where riders were, quite literally, being blown sideways.

The sight of a man as robust as Geert Steegmans being swept off the road and into a ditch was a striking demonstration of the severity of the winds, and many others suffered the same fate. "Once we turned left and started heading south, it was just carnage," third-placed Geraint Thomas said afterwards.

With 125km to go, the peloton seemed to split into echelons in slow-motion, such was the ferocity of the gale sweeping in off the North Sea. Eventual winner Luca Paolini could be seen grinding his way across to the front echelon, and he would have to repeat the effort later on, bridging across alone to the winning move with 70km remaining.

Paolini had already fallen twice by that juncture, changing his bike on each occasion, and he had one more pursuit to make when he was dropped on the final ascent of the Kemmelberg. "I was on my third bike of the day, and I think the pressure in the tyres was too high, so I wasn't able to push it on the pavé," said Paolini, whose career would be ended by a positive test for cocaine at that year's Tour de France.

Everybody had a war story from the afternoon. Thomas was blown off his bike and into the ditch, but the Welshman recovered to re-join the six-man group that disputed the finale.

Winner of E3 Harelbeke two days earlier, he was the man on-form, and the QuickStep duo of Niki Terpstra and Stijn Vandenbergh had eyes only for him when Paolini seized his chance with 5km to go. "I looked at everyone in the face, and I saw we were all finished – alla frutta, as we say in Italian," said Paolini,

Thomas, meanwhile, was outsprinted for second by Terpstra, but on a day where only 39 riders completed the course, the result was almost an afterthought. "We knew it was going to be windy," Thomas said, "But, man, it was hard just to stay on the road."

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.