'Shocking, scarring, and a portal into hell' - Svein Tuft recalls the brutality of the Classics in new book

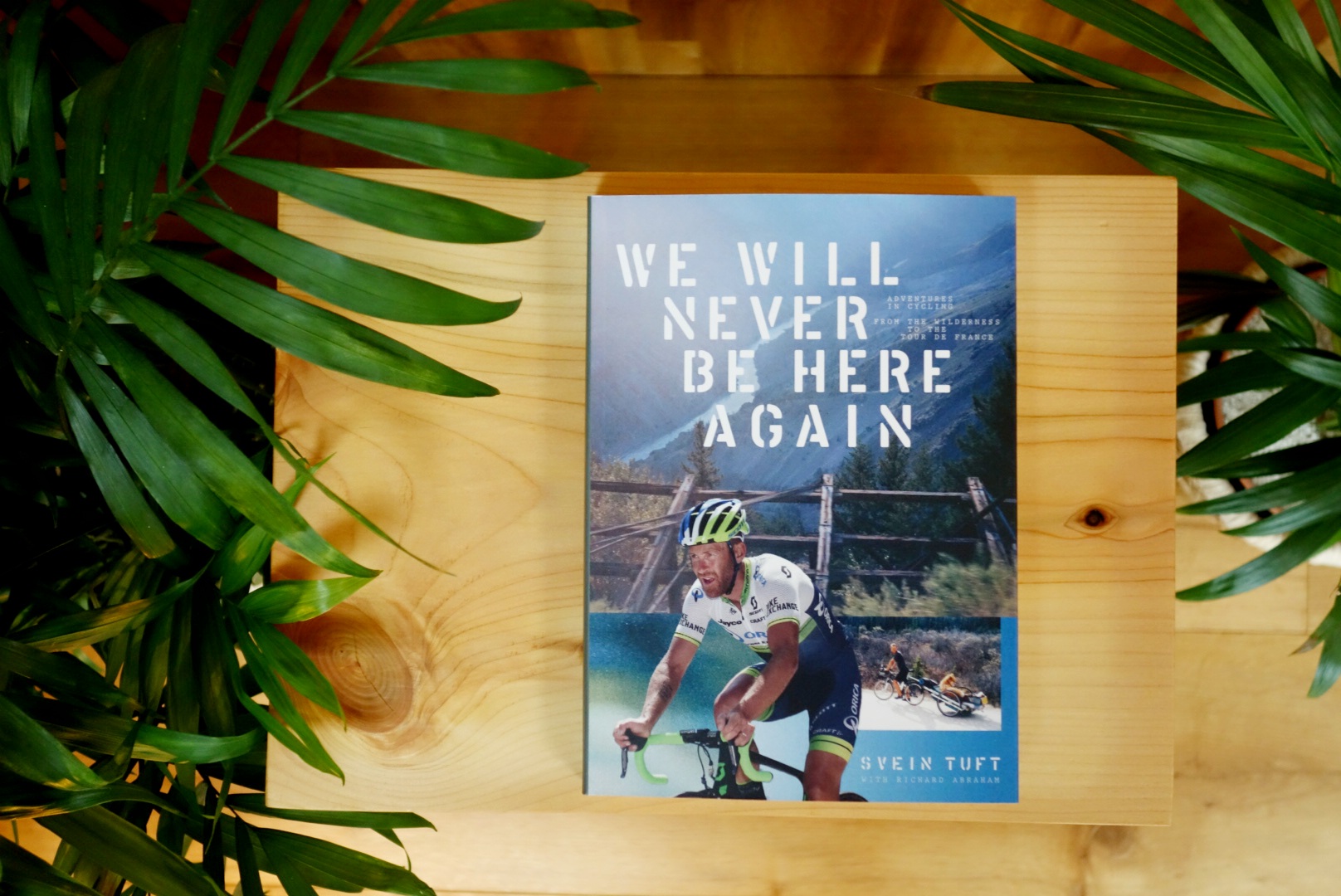

In his recently released book 'We Will Never Be Here Again: Adventures in cycling from the wilderness to the Tour de France', the Canadian ex-pro describes the chaos of the Classics

The following is an extract from We Will Never Be Here Again: Adventures in cycling from the wilderness to the Tour de France by Svein Tuft and Richard Abraham.

Recently published, Svein’s autobiography tells the story of his remarkable life both as an adventurous young man growing up in the wilds of the Pacific Northwest and as a professional rider for a decade and a half.

From bike-touring to Alaska to racing in South America through to his career high of wearing the maglia rosa at the Giro d’Italia, the book is also about how Svein’s backstory brought a unique perspective to the life and career of a professional cyclist.

In this extract, Svein recounts his experiences in the Spring Classics as a relative newcomer to the sport at the age of 31. Here, he explores risk-taking, insider knowledge, and why, in the Classics above all other races, the outsider always stands a chance.

We Will Never Be Here Again: Adventures in cycling from the wilderness to the Tour de France is available now in softcover and ebook.

***

The Classics. They are shocking, they are scarring, and if you’re a new guy then they are a portal into hell.

When you watch the Classics, it can sometimes look like guys are just riding along and nothing is really happening. What you don’t realize is that the guys at the front are riding 500 to 600 watts to dictate the pace and to get to the next little turn in the road at the front of the peloton. The Classics are raced from the front. When you know every single inch of those tiny little roads up there in Belgium, you have a huge advantage. When you come from North America, you don’t have a clue.

Most guys were left scrambling by the Pegasus debacle, but that same winter, a Canadian team called Spidertech took a step up to the ProContinental ranks, the second tier of the sport, and within a week, I had a contract. I was a bigger guy who had decent power, so people talked up my chances in the Classics, but without any idea of the reality. You can go there with peak fitness, perfect training, and still get your head kicked in. Success in the Classics comes down to local knowledge and how much risk you’re willing to take. And until you’ve raced down the Nieuwe Kwaremont to get into position for the Oude Kwaremont, you will never know how psycho bike racing can be.

That section of road is a key part of all those races in Belgium, and of none more so than the Tour of Flanders. The Oude Kwaremont is a cobbled climb. It’s pretty rough, pretty gnarly, and pretty long at 2.2 kilometres, but the gradient isn’t that steep: Just 4 percent average with the steepest no more than 11 percent. It’s a place where a lot happens—quite often it’s where the winning move will go clear—and it’s a great example of how bike races are controlled. If you’re not in the front 20 or so riders on the Oude Kwaremont, then you can wave goodbye to the front group when the smackdown comes. You can be in the best form of your life, but if you’re too far down the pack, you’ll never get back up—the roads are too narrow to move up—and so it’s imperative to be near the front.

The run into the climb is like a funnel. The road goes from a fast, wide descent onto a series of turns on narrow roads. You find yourself doing 100km/h down the Nieuwe Kwaremont, which is a wide main road a kilometre from the bottom of the Oude Kwaremont. It’s a 100km/h washing machine. Guys are taking risks the entire way down in the hope of moving up to the front. The best riders are able to float around and hold position near the front (but never on the front), and right before the first turn after that descent, they will do one massive hit—take one calculated risk—to move up to prime position.

Now we’re on the goat paths, those narrow concrete block roads that are so typical of Flanders. The old boys’ club make it to the front: The Belgies, the best mates, the training partners, the ones who know the roads better than the back of their hands. Most of them have been riding those roads together since they were nine years old. It’s in their interests to control the race and so they ride a steady 30km/h into the climb, bunching up the peloton and blocking off the road. They’ve done their effort; now they’re recovering.

Meanwhile, out the back of the peloton, individual riders sprint to try to get back into the bunch and groups seek to take advantage of the lull to catch back on. But it’s too late, because those guys at the front are about to hit the base of the cobbled climb, fully recovered, ready to light it up. Maybe you take some crazy risks. Perhaps ride down the grassy verge or over some rocks to move up 10 places. Or you ride 550 watts up the whole climb—just as hard as the front guys. But you still end up out the ass of the peloton by the top. You’ve now got a 500-metre gap between you and the front of the race. How are you closing that gap to the best riders in the world? You’re not.

Now repeat that experience 15 or 20 times, throw in some crosswinds and foul weather, plus plenty of mechanical issues caused by the cobbled roads, and you have a one-day Classic.

I like to take calculated risks, and I was used to taking them while climbing in the mountains. You have to understand the elements—what you’re up against and what you’re trying to achieve—but, whether you succeed or you fuck up, in the mountains it’s your choice and your problem. You’re never in control but your decisions can help dictate the outcome for you. In the Classics, risk-taking is just mayhem. It’s totally out of control.

I’m not afraid of crashing—I’ve crashed so many times doing all kinds of stupid shit—but I don’t like that aspect of humans where decisions are taken out of desperation. Even so, in 2011, I made a decision: I’m going to train the house down and take risks and not give a fuck. That didn’t necessarily mean saying fuck everyone else, it just meant telling myself that when something happened in the race I had to be there. When the peloton split, I had to be there. When Fabian Cancellara attacked, I had to be there. I realized that if I could make it through the shitticane of attacks that fragment the peloton, then the racing afterwards wasn’t actually that difficult. The game isn’t hard; the hardest part is being there to play it. And as one of the bigger-name riders on Spidertech, this would be my opportunity to try.

E3 Prijs was the closest thing to the Tour of Flanders that Spidertech was racing that season and so I made it my target. It’s 200 kilometres long, about 60 kilometres less than Flanders, but it goes over all the same roads and, since it takes place a week beforehand, it acts as a dress rehearsal race for all the big hitters.

I had learned enough about the Classics to realise I wasn’t going to make it to the front of the bunch with all those guys. I knew I had to get up the road ahead of them, so that I could be ready when they made their first moves. That would involve spending vast amounts of energy to get in the breakaway and stay there, but I couldn’t afford to get in the breakaway from the gun because I would have nothing left for the finale. I just needed to be the no-name guy up the road when things settled down into a good old-fashioned bike race. In the Classics, more than anywhere else, a no-name guy stands a chance of pulling off a big win against the odds.

On a hard section of road with around 80 kilometres left to go, the race blew apart. The early break was still up the road, but the big teams were trying to slow things down so they could regroup. I chose that brief lull as my moment to attack. A Dutch guy, Bram Tankink, came with me, and we did a two-man swap-off to catch the break. By the time Fabian Cancellara made his attack out of the bunch (on the Oude Kwaremont, of course), we were already up the road. When he joined us, there were 19 of us out front and 30 kilometres to race. Just the way I wanted it to be.

From then on, it was like going into the 12th round of a boxing match. Guys were hitting out to get a sense of how likely everybody else was to chase them down. Everyone knew that if Cancellara went, they had to be on his wheel. I had been in similar situations in jiu jitsu. It’s easy to panic if someone is about to choke you out, but you learn that if you panic, you will end up in a far worse situation. Bike racing can be a beautiful thing in those moments, because it comes down to how much you can give. It’s a survival moment, and you start tapping into deep, instinctive, mental and physical reserves. I believed I could win, which was perhaps delusional, but if you don’t believe you can win, then you forget about it.

I covered every move, digging deeper and deeper. In retrospect, the best thing for me to do as a no-name in the group would have been to sit at the back, start smashing food and water and follow everything. Then maybe I could have made one big move. Maybe Cancellara would have been off already. Maybe I would have run second. But I was caught up in the moment. When Cancellara did finally go, nobody could follow him. I had wasted too much energy and ended up 11th [sic 13th]. As much as I was disappointed with that result I was beaming, filled with good energy. I was up there, fighting in the finale with some big names. I had never managed that with Slipstream. I was thirty-three years old, but I was still progressing as a bike racer.

We Will Never Be Here Again: Adventures in cycling from the wilderness to the Tour de France is available now in softcover and ebook.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.