Shipping rates and €900 paint jobs: A deep dive into why some bikes cost so much money

From raw materials to retailer margins we tot up what makes a superbike cost so much

Performance cycling sits in a rather unique place among vehicular sports. Nobody can buy a Formula 1 race car, and neither can any Tom, Dick, or Harry rock up to a marina and put a down payment on an America’s Cup boat. With cycling though, thanks to the Union Cycliste International governing body insisting that every piece of equipment used in the professional peloton also be available for sale publicly, one can, with deep enough pockets, order the same bike as the pros use.

There are of course some loopholes and grey areas; no sport is without these and they make for an interesting narrative for gear nerds. It’s not unusual to see equipment, especially at the Olympic level, priced so outlandishly that nobody of sound mind would ever think of pressing the ‘buy now’ button, hidden at the centre of a maze of menus and sub-menus to make things even more tricky. Sometimes equipment is simply ‘price on request’, or in the case of custom gear lead times of many years are quoted as a deterrent to ensure only the national team in question retains access.

Ignoring the murky world of Olympic track cycling though, it is relatively easy to work out how much a WorldTour bike costs. You simply google all the constituent parts, find the prices for each, and do a bit of adding up. We’ve already done that bit before though for Tour de France bikes. The short version is that a WorldTour bike costs anywhere between £12-13k, or $15-17k in freedom currency.

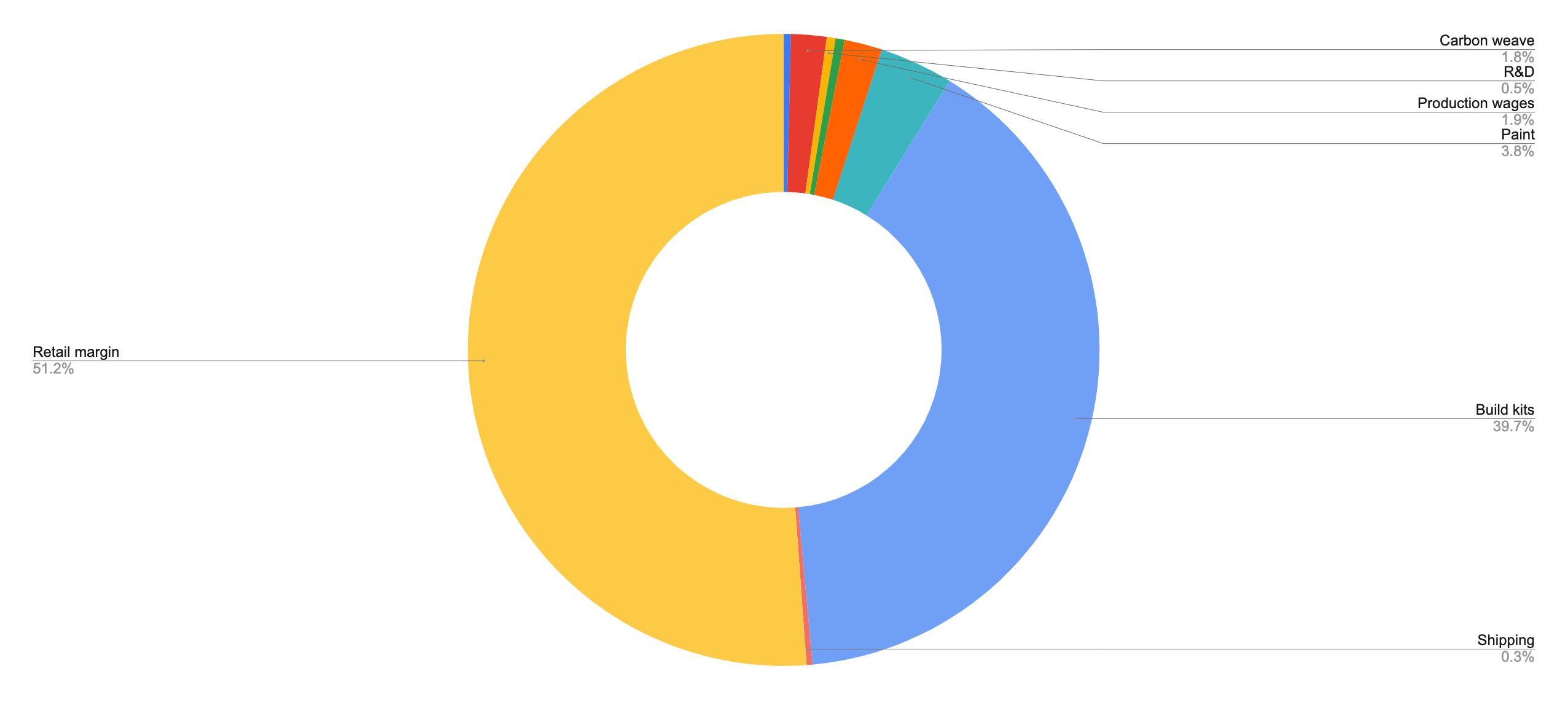

There’s more to cost than just the price tag however. There’s the cost of production and transport, not just of the bike and the components, but of the raw materials too. There’s middlemen, dealerships, and sponsors, meaning there’s essentially three different costs: Cost of a produced bike, cost of a retail bike, cost of a bike to a team.

In the coming sections, I’m going to attempt to demystify just why bikes cost as much as they do, drawing on some of my own experience - I am a mining geologist by training with a lot of background in raw materials, believe it or not - and calling in experts and those in the industry to help steer get as clear a picture as I can. Broadly speaking I'm going to use the Pinarello Dogma F as an example throughout. It's fabulously expensive, raced at the WorldTour level, and I've reviewed it recently. Moreover, Pinarello was happy to put someone up to chat with me about the costs involved.

The figures I’m presenting here are not by any means meant to be gospel, but simply a best estimate taking in all the information I can find. There will undoubtedly be areas where I under- or over-estimate, and some costs I cannot account for. The aim is simply to find out the costs involved with producing such expensive bikes, and whether they can justify their price.

Raw materials

Bikes, and bicycle components, are more or less entirely made of five things: Carbon, aluminium, steel, titanium, and rubber. I've written a primer on how bicycles are made for each of these materials besides rubber already if you want a bit of homework. There are undoubtedly more, but that’s very much the lion’s share now that nobody is racing magnesium Pinarello Dogmas anymore. If you want a fun fact, the last non-carbon bike to win the Tour de France (if you ignore Floyd Landis' actually winning it at the time) was a magnesium Pinarello Dogma in 2006.

Carbon fibre makes up the bulk of high-end frames, forks, cockpits, rims, and a fair few crank arms, brake levers, and other small tech too like bottle cages. It is entirely produced from oil. The chemistry is a little complex for the scope of this article, but in essence, a stable polymer thread similar to nylon is spun out and then passed through a furnace or two to carbonise it - literally turn it into carbon. These fibres can then be bundled together to create a carbon weave, covered in a bit of resin in a mould, baked, and there you have it.

It’s relatively simple, and at its most basic the raw material (taking Brent Crude as the oil price) is worth about 77 dollars a barrel.

Let’s assume for the sake of argument that 4kg of a 6.8kg race bike is comprised of oil-derived products. One barrel of oil is approximately 300lbs, or 136kg of oil. You need roughly two kilos of polyacrylonitrile (that nylon-esque fibre I mentioned earlier) to get one kilo of carbon fibre, so each barrel has in very rough terms the potential to make 68 bicycles worth of carbon fibre.

More quick and dirty maths using the Brent Crude price makes a WorldTour bike’s worth of carbon fibre worth approximately $1. This is a hilariously small number, but remember that’s just the raw carbon fibres themselves. There’s the cost to run the furnaces to make them, and the associated chemistry of the resin, and the shipping of these raw materials to factories to turn them into carbon weave before we even get to making a product.

Sign up to the Musette - our subscriber-only newsletter

Metals are different, and a little easier to comprehend. Aluminium, steel, and titanium all occur as deposits of minerals in the earth’s crust, and all need extracting, a great degree of mineral processing, and smelting before you get to saleable metal. I’ve explained this in more detail in my piece on how bikes are made if you’re curious about the actual production of raw materials. Steel is usually sold as steel products rather than ingots (rebar, big coils, that sort of thing) which slightly complicates things but if we roughly equate ‘Structural Steel’ from the stock market to the high-quality steel used in some ball bearings, chains, and sprockets then we’re looking at £1,300 per tonne, or £1.30 per kilogram. Again, the raw material cost of steel in a bike is tiny, a matter of £1-2, or a similar amount in dollars. You’re looking at the same sort of raw material cost for aluminium too, and while titanium is a much higher material cost - in the region of $35-50 per kilogram - there’s far less of it utilised on a WorldTour bike.

Rubber is a different kettle of fish entirely, derived as it is from tree sap. The average rubber price last year was around $1.50 per kilogram, which is more than enough for a pair of tyres. All in all, just looking at the raw materials, a WorldTour bike can cost little more than £30/$40. How, then, do we end up with a price tag north of £12,000?

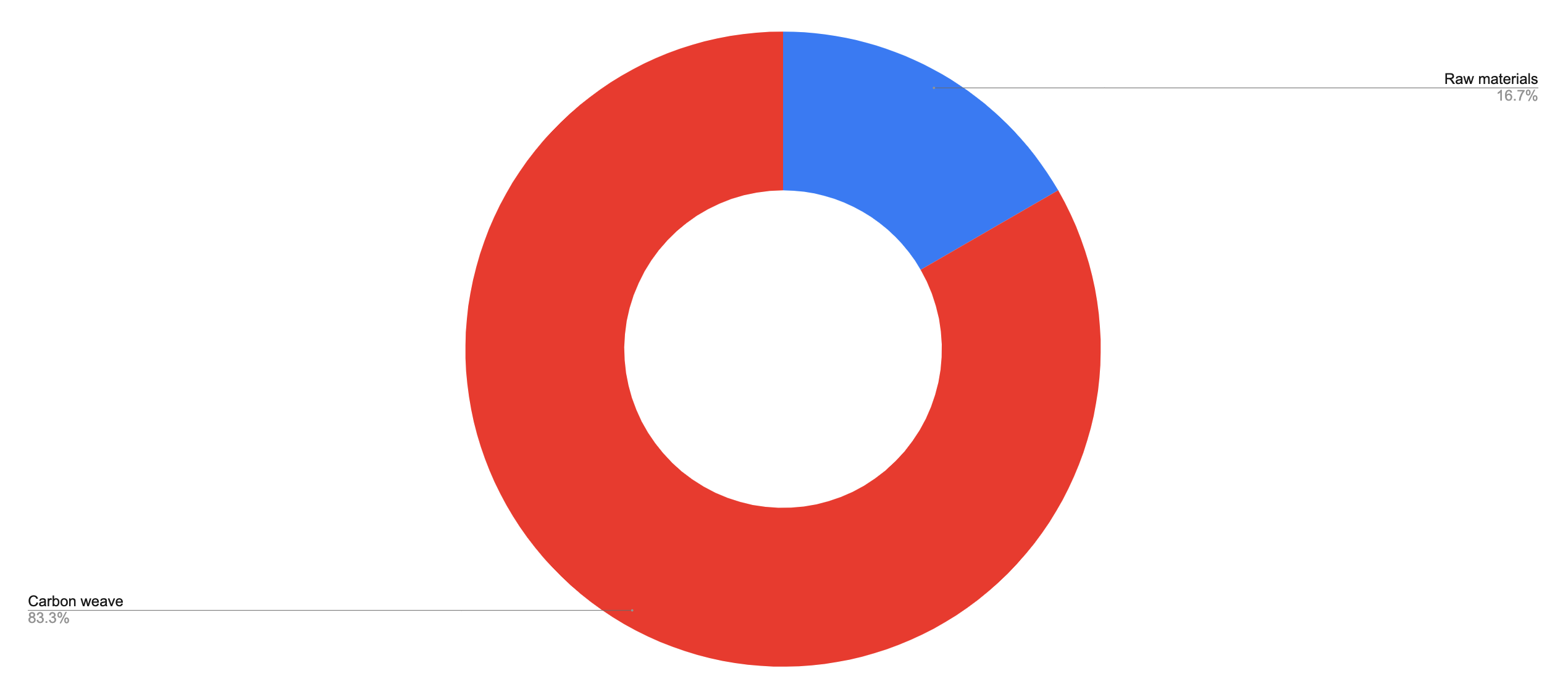

Production of carbon fibre

Producing carbon fibres, both the fibres themselves and the pre-woven sheets, from the raw materials essentially involves running a series of giant furnaces. In general the higher the modulus of carbon (the stiffer it is) the more expensive it is to produce. Toray is the biggest carbon fibre producer on the market, and it produces a wide variety of fibre options, all labelled with handy numbers.

T700 is a general purpose, do-it-all fibre and something like this will make up the majority of a bike frame. Higher performance frames may go up to something like T1000 or higher, but while the frame may show a higher modulus carbon on the frame, such as Toray’s M40X in the case of the Pinarello Dogma, this doesn’t mean the entirety of the frame is made using such fibres. They will be reserved for specific areas like the bottom bracket. The stiffer the fibres the more brittle they are, and so are less well suited to being placed in complex areas of the frame.

Sadly the main player in the carbon fibre world, Toray, declined to be interviewed for this piece, and brands weren’t forthcoming either. We can still make some educated guesses here though, as it is possible to buy carbon fibre in small quantities as a consumer. A bike frame needs about 1kg of carbon fibre once you account for the offcuts wasted as part of the production process.

Small scale sheets of T700 carbon weave work out at around €15/m2 and weigh about 150g/m2. Taking a full bike at 1000g for easy maths that means a bike frame utilises roughly 10m2 of weave in ballpark terms, or around €100 in carbon cost. Higher modulus carbon like T1000 or M40X as is used in higher spec frames can be 2-3x as expensive, but only makes up a small (5-10%) portion of the frame by mass, and this increase in cost would likely be offset by the far cheaper wholesale cost for brands using vastly greater quantities of carbon fibre than single consumers can purchase.

Speaking to Andrew Juskaitis, Giant Bicycle’s worldwide Senior Product Marketing Manager I was told that a bike like the Giant TCR involves 36m2 of carbon fibre sheet. At €15/m2 this would mean it’s about €540 in carbon, but Giant, being the biggest producer of carbon bicycles, is naturally not going to be paying the same rate as you or I would if we wanted to buy the odd bit of Toray off eBay. For the sake of argument, let’s round this €100 figure up to £200 to cover not just the carbon in the frame, but the resins too.

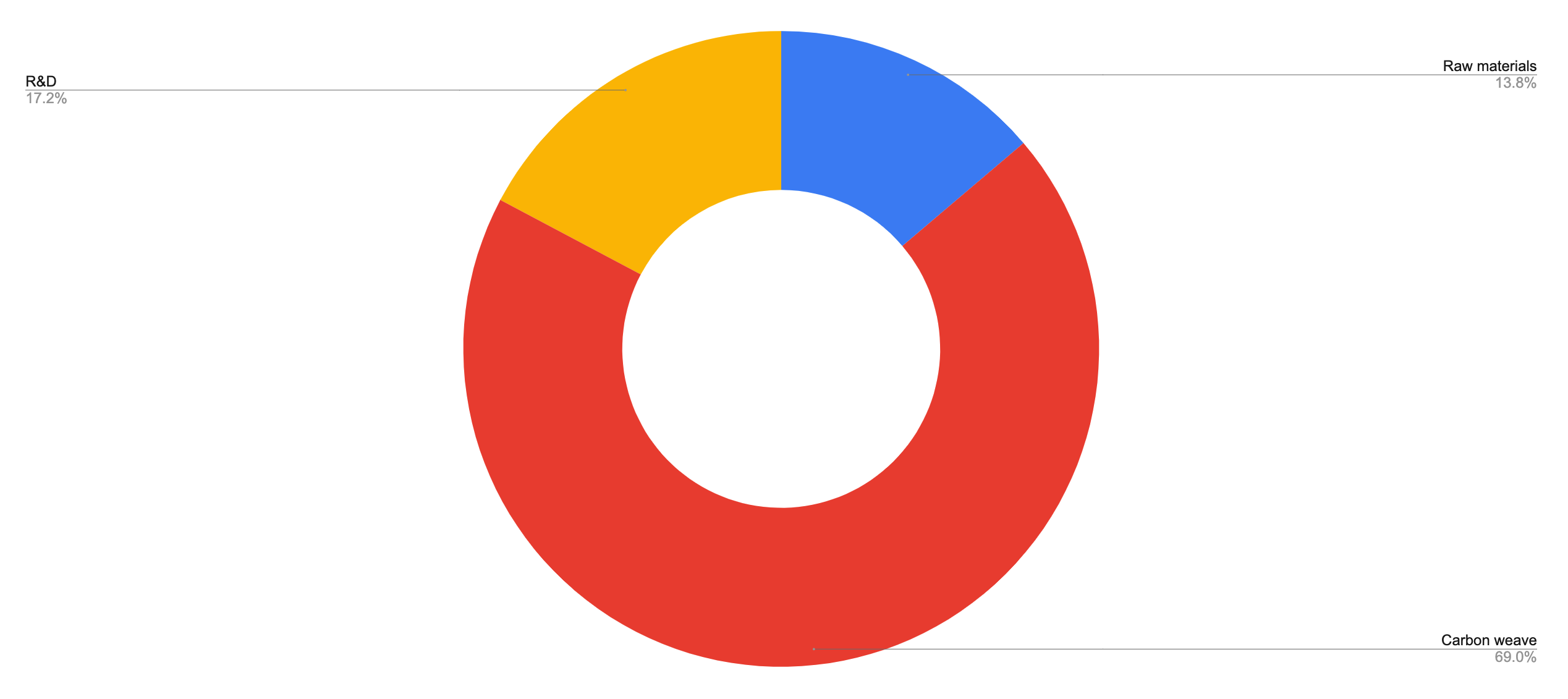

Research and development

Speaking with Federico Sbrissa, the Chief Marketing Officer at Pinarello I asked him how much development resource goes into something like the new Dogma. While the team won’t work solely on one thing all the time, I was told that the latest Dogma took the equivalent of the whole R&D team of seven people one full year of work, not including any external consultant costs like outsourcing wind tunnel testing.

According to payscale.com, the average salary for an Italian Design Engineer is €40,000/yr, meaning that in R&D costs alone a new top-end road bike costs in the region of €280,000 (approximately £230,000 or $300,000) in salary costs alone. Factor in some time in the wind tunnel, which are commercial units as we know from our own wind tunnel tests and you’re looking at something in the realm of £300,000. A brand like Specialized can cut the cost of commercial wind tunnel usage by simply building its own wind tunnel, but the cost of building a wind tunnel isn’t exactly small…

A big number for sure, but it all depends on how thin you spread the jam. If the brand in question makes more frames this cost is spread more thinly across each individual frame. Fewer bikes, greater cost per frame. Sbrissa, while being extremely helpful, declined to tell me how many Dogmas Pinarello produces so let’s ballpark it at 2,000 frames a year over a three year product life, broadly in line with a figure Rob Gitelis of Factor Bikes provided to Escape Collective in a recent article, that’s £50 per frame.

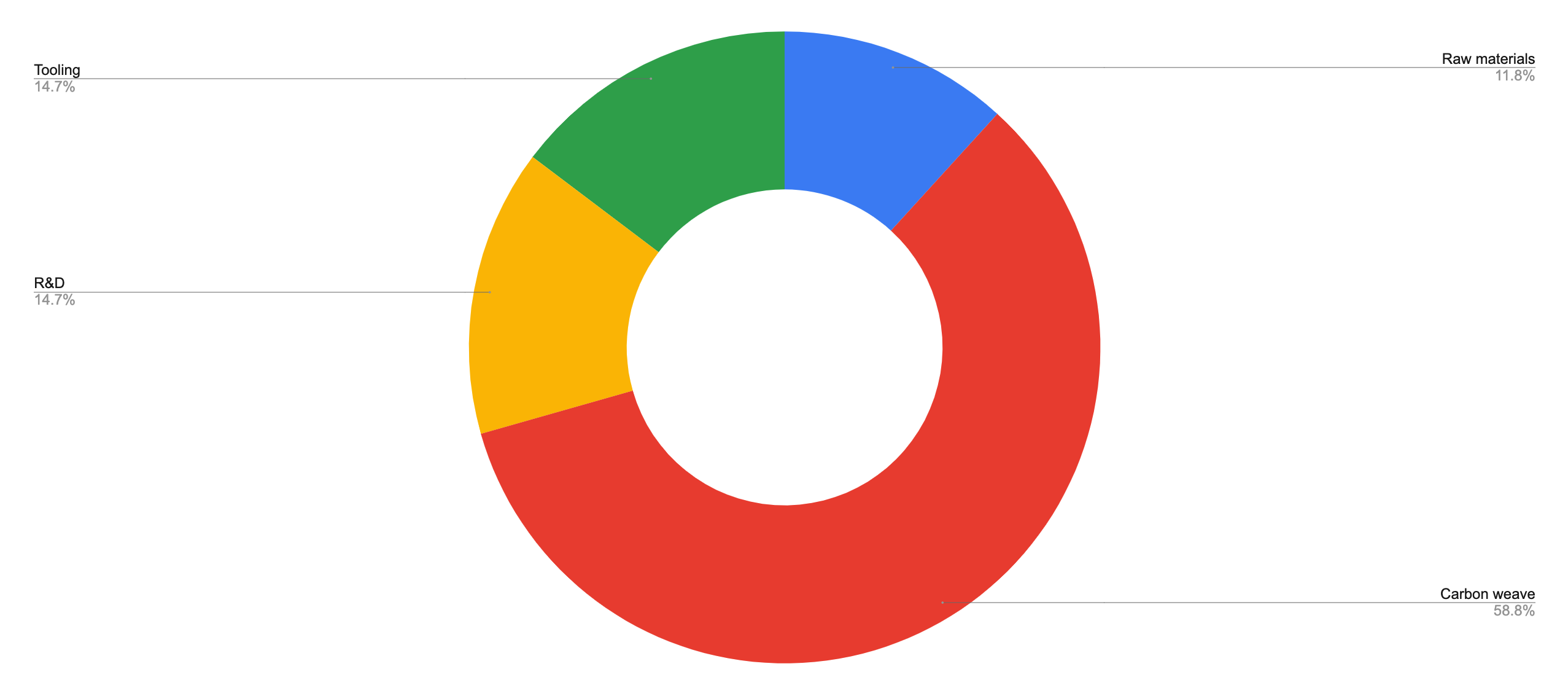

Cost of production

Recently I took a visit up to the National Composites Centre, just north of Bristol here in the UK. It was a fact finding mission for another piece I was working on, but while I was there I picked up a lot of bonus information about how carbon fibre products are made. I am going to focus in on carbon fibre primarily here for a bit, as the manufacturing is slightly more complex, and other than small scale titanium outfits and deep custom steel, most of the very expensive bikes on the market are carbon.

Every carbon fibre product needs what’s known as ‘tooling’, which is the industry term for the mould in which the raw fibre sheets are laid before going into the pressure cooker. For a frame, you’re looking at something in the region of £30-50,000/$65,000 for a single size (not necessarily a single mould, but multiples of the same size mould to allow more than one frame to be produced at once. If you’re a company making an all-new model in a run of six sizes that’s £300,000/$400,000 just in the cost of the moulds. With this alone in mind, it’s now a little easier to conceive of why the difference between the raw material cost and the cost of a finished product is so great. If you take a bike like the Pinarello Dogma, which is available in 11 sizes, that could add up to over half a million pounds just in the cost of the moulds.

Taking a conservative figure of £300,000 for the outlay for the cost of the tooling and dividing that total cost by our ballpark figure of 6,000 frames (2,000 per year for three years) that’s £50 per frame.

Not a huge cost on a per-frame basis, but a massive outlay up front, and so some brands get around it by using what's known as an 'open mould' system. Bike factories have off-the-peg moulds ready, and the brand can then just spec the carbon it wants to be used, the layup, and crucially the level of quality control. Using this system means no outlay for moulds, and if it isn't trying to make a class-leading superbike a relatively simple layup will be easier and require lower levels of QC to make sure it is safe.

It's this last point that is a real differentiator between cheap and expensive carbon bikes. A fake frame from AliExpress, or even a no-brand open mould option has no brand associated with it. No brand means nobody to point to and potentially sue if or when it fails. No risk, so no real need to invest time and money into rigorous QC procedures.

This is compounded by the fact that it’s nearly impossible to mechanise the production once you have the moulds. Producing a carbon fibre frame involves pieces of pre-cut carbon weave being placed by hand into the right place, in the right sequence, without any wrinkles or shears. It’s incredibly labour intensive, and this is why almost all production takes place in the Far East, where wages are lower. The more complicated the shape the longer it takes to layup, and with increasingly stiff carbon fibre (higher modulus, as it is called) the difficulty is compounded as these are more prone to cracking. Stiffer carbon makes for stiffer bikes, but with this increased stiffness comes an increase in brittleness too.

Things are a little more simple when it comes to the production of high-end metal parts. Titanium and even aluminium can be 3D printed now. Colnago uses a factory in northern Italy that normally produces medical implants. The machines are already there making something else and just need a new model loaded into them. Machining, forging, all can be mechanised more easily and at small scale and as such you can find far more small scale component manufacturers using metal than you will with carbon. Tactic, White Industries, Raketa, Paul. Economies of scale still come into play though, which is why the little-produced £1,000 tactic hubs are more expensive than more widely seen equivalents from the likes of DTSwiss and others.

There is an assumption among many that carbon fibre bikes are all more or less the same. Many people question why one carbon fibre bike can cost £12,000 and another can cost a fraction of that. The tooling cost is one thing, with more intricate shapes costing more, but the use of higher strength and stiffness carbon fibres to reduce the overall frame weight comes with added manufacturing complexity. On this point, I consulted the National Composites Centre directly.

In general, lower-end frames use "mostly intermediate modulus fibres like T700 with some areas using industrial grades (T300 and similar) with extensive use of woven fabrics across all parts of the frame." This means the carbon itself is cheaper, but it’s also more forgiving to work with and "requires less design time to make a decent frame." The flip side to this is that you need more of it to get the desired frame properties, and so it cannot be made as light, or as stiff without becoming excessively bulky.

At the mid range I’m told that "frames seem to have settled on spending money on design and using a single grade of fibre" - generally T700-800 or so - but with a greater emphasis on layup quality. "This more careful use of fibres means they extract better performance from a mid-range material than less careful use of fancy carbon."

When you get to the top end, utilising very high modulus fibres and aiming for the lowest weight while maintaining strength the manufacturing gets more tricky. ‘The trade off is more complexity (and so cost) in manufacture and as you optimise the structure you rely more heavily on these small quantities of high performance materials to have a safe frame. That is why quality control is more important on high-end frames because these materials need to be right so they take the loads they are capable of and spare the lower spec materials from excess load.’

So while on the surface two carbon fibre frames may appear the same, underneath the paint there are differences in materials, manufacturing time, and quality control. In order to get a handle on how many man hours go into a carbon frame I called upon Andrew Juskaitis again, Giant Bicycle’s worldwide Senior Product Marketing Manager:

“From creation of the composite sheet to placing the completed bike in a box, it takes approximately 25 hours of hand work to build a TCR Advanced SL.”

With this in mind, especially considering Giant is the biggest producer of carbon bikes, producing frames for other brands in its factories, it’s possible to build a pretty representative per-frame cost in wages.

According to Bicycle Retailer and Industry News, the average annual salary for a Taiwanese manufacturing employee in 2022 was $23,697, or roughly $11/hr. That means each frame has a cost of $275 in wages, or £213.

This doesn’t include the extra cost of what can be a high-intensity manufacturing plant. Water use, electricity to run not only general power but the autoclave, regular maintenance, and rent all add to this cost but are impossible to pin down to a general expenditure across the industry.

When a high-end bicycle can easily cost more than a motorbike it can be a little hard to fathom why. Racing bicycles are made to be as light and efficient as possible because the rider is the power source. A cyclist can push about 0.3 horsepower, which is dwarfed by the output of even a modest motorbike, and as such motorbikes aren't made to be so light. What's more, if you made many parts of a motorbike out of carbon it would melt.

The structural parts of a motorbike are, in general, forged and machined to tolerance. This uses relatively cheap raw materials, and is easy to mechanise. The non-structural bits can be made of carbon for high-end race bicycles, but they needn't be load bearing and so require less R&D, and more often than not are injection moulded plastic, which is again easy to mechanise and uses extremely cheap materials.

Paint

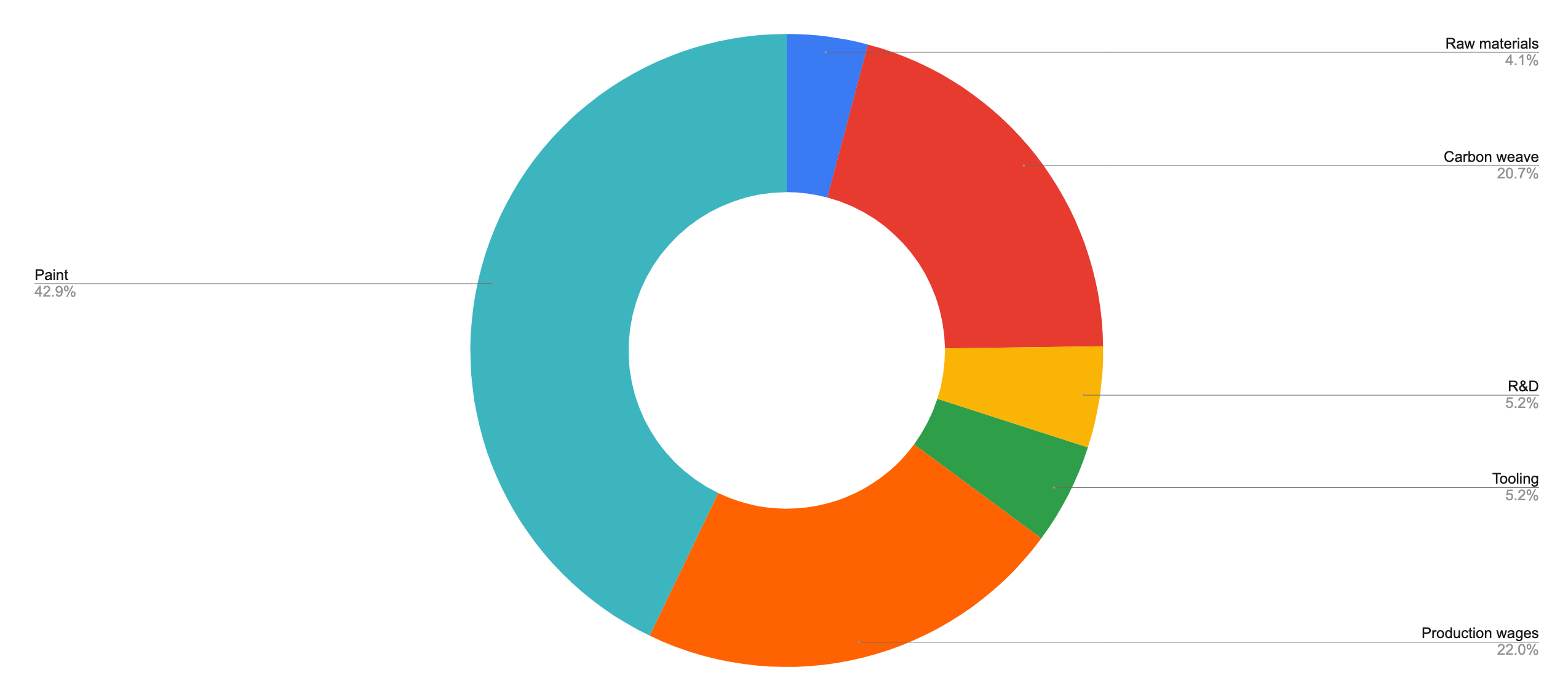

Paint can vary wildly in cost, and this was something I quizzed Sbrissa about regarding the Pinarello Dogma, primarily because I have tested it recently and it comes in a particularly lustrous paint scheme.

The classic black with white, or block colour, logos I’m told can cost as little as €50 per frame, or even less. When I visited the Colnago factory I saw first hand how little paint is applied to a bike like the Colnago V4Rs in its UAE Team Emirates livery, but if we take something like the Dogma in its pearlescent blue then costs begin to spiral wildly.

I am told the paint itself costs €2,500/kg, or €2.5 per gram. Each frame requires a pair of colours to achieve the pearlescent effect, adding more up front costs, but on a per frame basis it takes around 350g per frame, meaning the cost in paint alone is €875 (approx. £730/$940).

On top of this, paint is a skilled job involving a lot of prep time. Sbrissa was naturally unwilling to divulge the salary of the Pinarello paint technicians, but did indicate that they were on a higher wage than those in the R&D department. Taking a ballpark figure of €55,000/yr, or around €25/hr, a frame that takes 5 hours of work to complete (what I’m told is involved for the most complex paint schemes) this adds an extra €125 to the total cost of high-end paint, making the total cost essentially a cool, round, €1,000, or £830/$1,080 in other currencies.

Pinarello, it must be said, doesn’t charge extra for this paint, and I have been told in the past that the simple black paint schemes are always the best sellers, and so the cheaper cost to produce these subsidises the expensive pearlescent options. In the name of rough estimation let's simply halve that incredible £830 figure to £415 to create an average cost. Without knowing the number of black frames versus pearlescent ones it’s impossible to do otherwise.

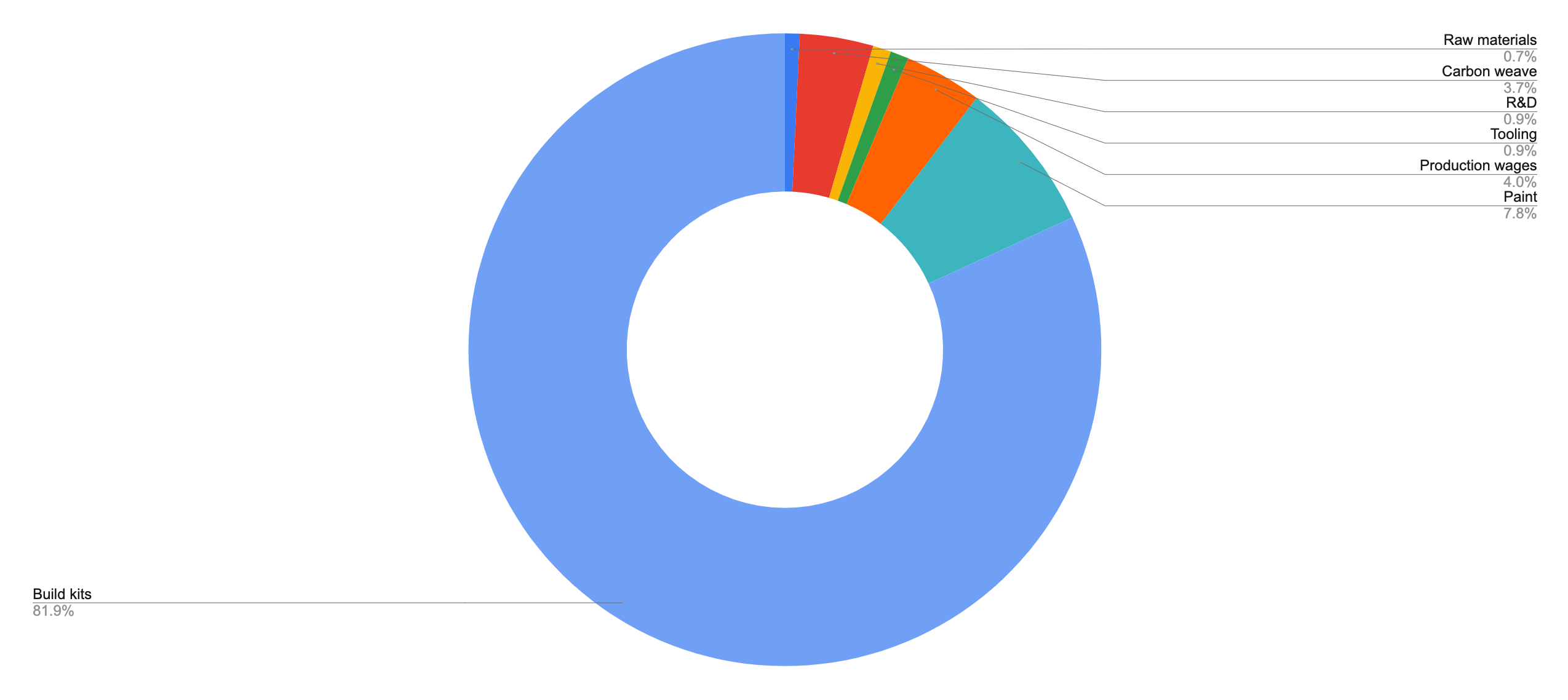

Components

Continuing with the example of the Pinarello Dogma for now, the model I recently reviewed was about as top flight as it’s possible to be. Shimano Dura-Ace groupset, Princeton Carbonworks wheels, an integrated cockpit. The works.

Speaking to Sbrissa again I was told there really isn’t much difference between what consumers pay for build kit setups versus what a brand like Pinarello would pay, especially taking into account the sale prices the industry is seeing across the board.

The frameset accounts for only about 35-40% of the cost of the bike, which by our calculations so far is just shy of £2,000. This doesn’t account for any profit the brand in question is perfectly entitled to take, as well as the costs associated with running a business which all have to be realised by the sale of its products, so this number is so far a vast, and very generalised underestimate.

Once you add in the componentry cost, say £2,000 for Dura-Ace, A further £2,300 for the wheels, and maybe £70 for a really decent set of tyres you’re adding £4,370 to the total cost without even blinking.

While brands will often spec in-house componentry too, as Pinarello does with its Most cockpit, that componentry still requires R&D, raw materials, and manufacturing, which do still add to the cost.

High-end components especially have become more expensive. Inflationary costs are one thing, but the simple fact is that hydraulic braking systems and in particular electronic groupsets are more expensive to produce than their cable-and-spring mechanised forebears.

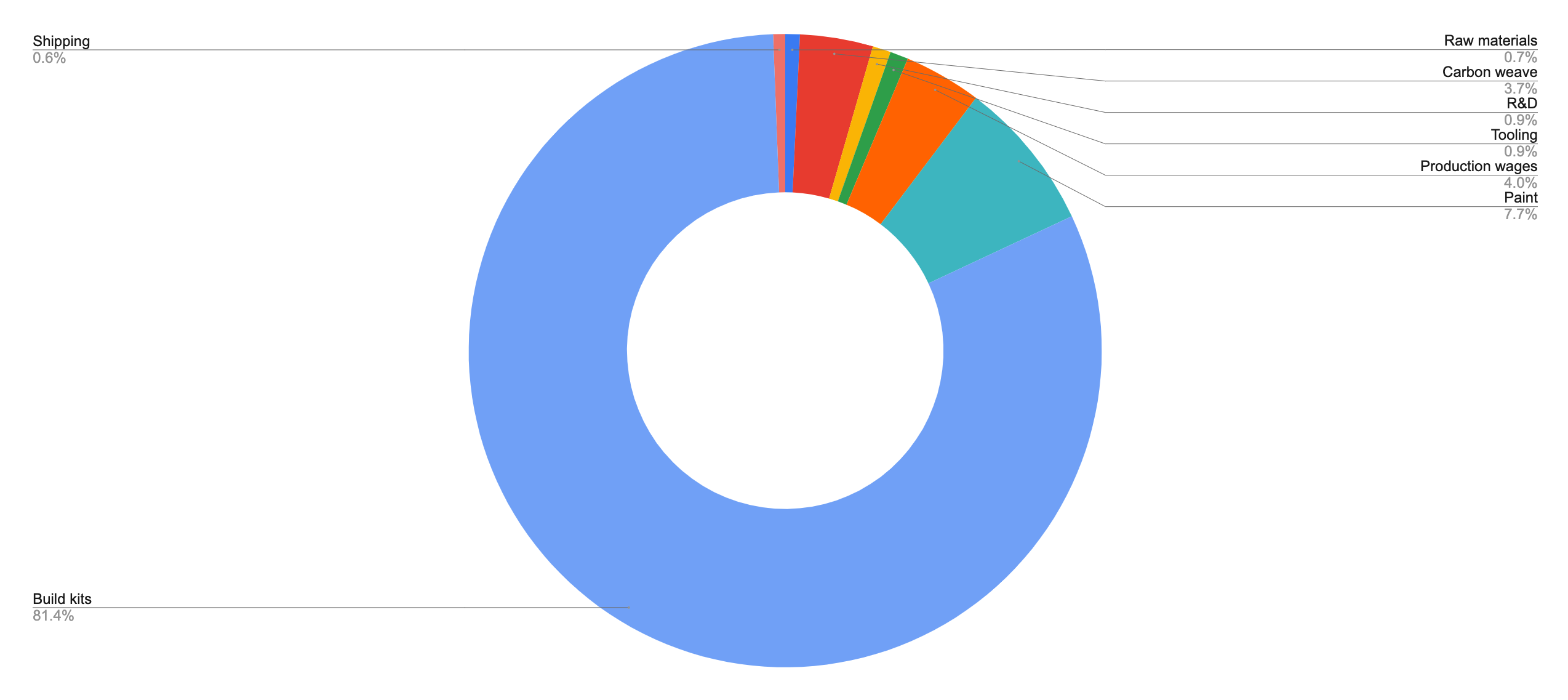

Shipping

If we thought about bikes as a bulk commodity in the same vein as iron ore and wheat the cost per frame to ship all over the world would effectively be zero. Giant container ships can carry loads of 400,000 tonnes, or roughly 57 million 7kg superbikes.

Fortunately for anyone buying a superbike, things are shipped a little differently for commercial cargo. I am lucky in many ways to have a wonderful partner, but for the purposes of this article I am also lucky in that her father is Capt. George, a former commercial tanker Captain, who I quizzed about shipping.

“Most stuff is moved by container these days,” he tells me, “either a 40ft or a 20ft container. Economies of scale dictate that a 40ft container is cheaper. Costs are per container type, with a basic box being the cheapest, and more for refrigeration (unnecessary for bicycles).”

There will be an upper weight limit for each container, though as I’ll get into a lot of bikes packaged in boxes is empty space for protection, and the bikes are extremely lightweight, it’s unlikely that a container even rammed full of bikes is going to hit the weight limit.

Interestingly the cost isn’t necessarily a case of getting it from A to B:

“Cost will be dictated by the route and the timeline. Cheaper will be a longer timeline, stopping at multiple ports en route, with direct shipping more expensive. Prices can be heavily impacted by political issues, with ships having to change routes to avoid piracy or war zones, but actual rates can be found by digging around online: You’ll have roughly 56m3 of space to play with in one container.”

Armed with that info, plus what I know about bike boxes (given that one turns up at the office more or less weekly) we can do some more quick maths.

A bike box is roughly 1560x30x80cm. Some come shipped in my more compact boxes, but this is a pretty good approximation. This is a total volume of 0.36m3, meaning in a 56m3 container you could pack 155 bike boxes in. Palletising makes things easier, so let's knock that down to 120 bikes for the sake of argument.

Google is a wonderful tool, and was swiftly able to tell me the current going rate for one 40 ft container from Taiwan to Rotterdam in the Netherlands would take around 35 days and between $5.0-$5.5k, or almost exactly £4,000 to keep our running total neatly in the same currency.

Breaking that down to a per-bike basis, dividing that by 120 gives us a cost of shipping of around £33. This doesn’t account for all the other shipping that goes on. Bikes are often sent from the factory in Taiwan to Europe for painting, and components and raw materials are also transported by ship, but you can fit an awful lot more unpainted, unbuilt bike frames in a 40ft container than you can complete bicycles, so the costs are spread more thinly per item.

This doesn’t take into account the journey on either side of the seaports though, as road and air freight are vastly more expensive. Air freight, according to Juskaitis of Giant Bicycles, is reserved for only the most desirable parts:

“Shipping is, by no means, cheap (certainly true during the pandemic)). Most goods travel via ocean freight but a few, highly desirable products, are air freighted to their destination (which is extremely expensive).”

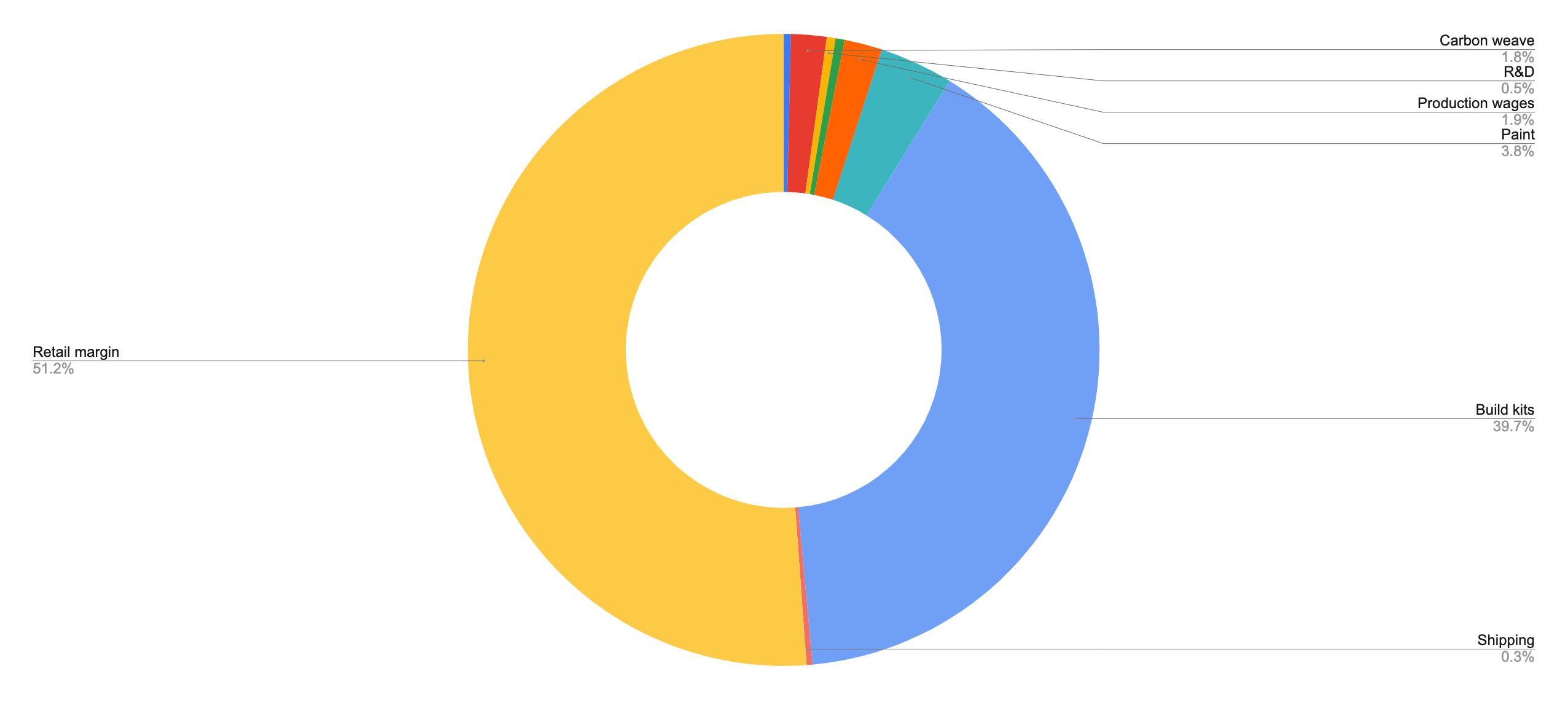

Distribution and dealerships

Traditionally the bike industry worked like this: Brand makes bike. Brand sells bike to distributor or dealer (distributor then sells to dealer if needs be). Dealer sells bike to customer. Each step in this process involves people making money, which is primarily why so many brands have gone direct to consumer. Canyon is the big player in this space, but even Specialized has gone direct to consumer recently.

Sbrissa from Pinarello was extremely candid with me when we spoke about dealership costs, telling me up front that 40-45% of the cost of one of its bikes is the dealer margin. That means for a £12,500 Dogma F, £5,625 of that is the retailer’s margin. This goes towards all the running costs associated with a fleet of brick-and-mortar dealerships, staff costs within them, as well as aftersales, servicing, and warranty, plus things like import and sales taxes which vary from country to country. That is not to say that £5k or so of a top-end race bike is dealer profit, that value will be a lot smaller. This value will of course vary from brand to brand.

Brands like Canyon get around this by just shipping bikes directly to you from their warehouses. Interestingly a Dura-Ace equipped Canyon Aeroad is cheaper than a Dogma F, but not by the same amount as the dealer margin I was quoted by Sbrissa. The retail cost is ultimately what consumers care about as that’s the value that gets deducted from their bank balance, but it does sort of stack up that the Canyon is more expensive than a Dogma in a weird sort of way.

There are undoubtedly more extraneous business costs wrapped up in the cost of a bicycle. Sponsorship of a WorldTour team like Ineos is undoubtedly a huge cost for a brand like Pinarello, but that cost is borne across the brand’s entire range of bicycles - assuming, in general, that pro sponsorship drives sales at all levels of the business.

Conclusions

I do want to make it clear that these figures are simply my best, educated guesses for these figures based on the information I’ve been given from a good few helpful and reliable sources. They are not intended to be exact, and there are simply too many costs involved in running an international bicycle brand for me to encompass in a few thousand words.

That being said, there is a common thread of comments under every high-end bike all across the media landscape: How on earth can you charge £XXX for a bicycle??

Well, given my running total for a top end bicycle, that I only totted up once I had all the approximate figures in for each stage, came in at £10,996, I hope this has in some way shed some light on that particular question.

If you subscribe to Cyclingnews, you should sign up for our new subscriber-only newsletter. From exclusive interviews and tech galleries to race analysis and in-depth features, the Musette means you'll never miss out on member-exclusive content. Sign up now.

Will joined the Cyclingnews team as a reviews writer in 2022, having previously written for Cyclist, BikeRadar and Advntr. He’s tried his hand at most cycling disciplines, from the standard mix of road, gravel, and mountain bike, to the more unusual like bike polo and tracklocross. He’s made his own bike frames, covered tech news from the biggest races on the planet, and published countless premium galleries thanks to his excellent photographic eye. Also, given he doesn’t ever ride indoors he’s become a real expert on foul-weather riding gear. His collection of bikes is a real smorgasbord, with everything from vintage-style steel tourers through to superlight flat bar hill climb machines.