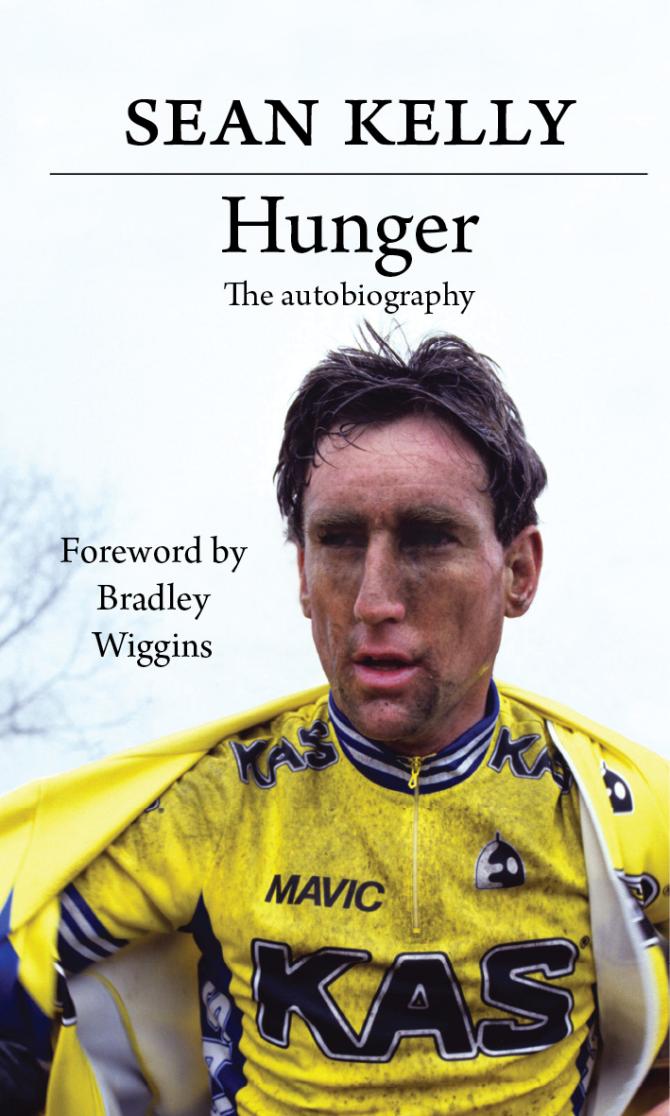

Sean Kelly: Hunger

An extract from his autobiography, 25 years after his Vuelta win

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 1987, Ireland’s Sean Kelly came within a few days of winning the Vuelta a Espana only for an extremely painful saddle sore to force him to pull out of the race with Madrid in his sights. The following spring, the world number one returned to the Vuelta more determined than ever to add a Grand Tour title to his impressive palmarès.

Kelly’s victory in the Vuelta was 25 years ago, at a time when the Vuelta was held in the spring, as the first of the season’s grand tours. But, as he explains in this extract from him new autobiography Hunger he almost lost the Vuelta before the opening weekend in Tenerife was over.

* * *

My strategy for the Vuelta was exactly as it had been the previous year. I knew I was not the best climber in the race but I was the strongest all-rounder. I could gain on my rivals by winning the time bonus sprints, doing well in the time trials and riding carefully in the mountains.

I was worried about the climbers because they could gang up on me and make life very difficult. Luis Herrera, the defending champion, would be a threat but I was more worried about the combined strength of the BH team.

They had four potential winners. Their leader was Alvaro Pino, who had beaten Robert Millar to win the 1986 Vuelta. They also had Federico Echave, Anselmo Fuerte and Laudelino Cubino, who were excellent in the mountains. Together they would be a very big threat.

The Vuelta started on Tenerife, which is a rugged, mountainous island. We almost lost the race before we flew back to the mainland. The first stage was unusual. The organisers split the bunch into groups of 36, with two men from each team per group. Each group then did a separate road race over a 17-kilometre circuit, with the winner of the fastest heat declared the winner of the stage.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

I had never done a race like it. I was in a heat with several of the favourites for the Vuelta and there was a chance to gain a few seconds over everyone else if our heat was the fastest, so we went flat out as soon as the flag dropped.

We gave it everything and at the finish, an Italian called Ettore Pastorelli took the sprint, so he was the stage winner and the first yellow jersey holder of the race.

The following day was a real dog of a stage and one of my worst days on a bike. Cubino, one of the dangerous men from the BH team, got into a small break and they gained a lot of time.

My Kas team-mate, Iñaki Gastón, was in the leading group but he was not a serious contender for the Vuelta so there wasn’t any great tactical advantage to having him up there – not when BH were represented by Cubino.

We were in two minds what to do. Usually we would not dream of chasing down a break with a team-mate in it but we didn’t want to give Cubino a present.

The rest of the Kas team was a shambles. We were falling apart. I dropped back to the team car at one point and passed Thomas Wegmüller, who was bent over by the side of the road. I asked him what was the matter. He groaned and said he had terrible stomach cramps, probably from drinking tap water. He pulled out of the race and it turned out he had dysentery.

Acacio Da Silva was in all sorts of trouble too. He said he had the same problem as Wegmüller and that was the last I saw of him until we got to the finish.

The rest of us had to do something to prevent Cubino from gaining a lot of time. None of the other teams were in a hurry to help us so we left it as late as we could, then got on the front and began to chase. At the finish, we’d cut the gap right down to a minute and 14 seconds, which wasn’t ideal but was a lot better than conceding three or four minutes.

As it turned out, Gastón won the stage and took the yellow jersey so the bluff worked out pretty well for us.

About 25 minutes later, Da Silva crossed the line, holding his stomach and complaining. I could never be sure with Acacio. He was such a talented rider but he would stay at home in Switzerland and leave his bike untouched in the garage for days. Then he’d turn up for a major race like the Vuelta and suffer terribly for the first few days because he hadn’t been training.

So I wondered if it was a bit of an excuse because he was the sort of guy who complained of a stomach ache one minute and downed a can of Coke in one the next.

Our team was in a bit of a state during the team time trial around Las Palmas too. We had lost our big engine, Wegmüller, and Da Silva was riding on one leg, so we did pretty well to finish sixth, although we lost another 1-11 to BH.

My plan, to gain time early in the race so I had a bit of a buffer in the mountains was in tatters already.

* * *

Once we reached the Spanish mainland, our directeur sportif, Faustino Ruperez, and I sat down to plan our strategy. There was no option but to sprint for every time bonus there was. Recovering more than a minute and a half a few seconds at a time was going to be a long slog but I had to get back on terms before the mountains.

To complicate matters, BH also had a pretty handy sprinter, Jorge Dominguez, who was always in the way, trying to stop me picking up the time bonuses. So, while I was battling for seconds here, there and everywhere, Cubino was enjoying a comparatively stress-free ride in the bunch.

It took me four days to claw back a minute and put me back in the hunt. Then, when we reached the mountains, the BH team tried to work me over. They sent Pino on the attack and he gained two-and-a-half minutes on the Puerto de Pajares stage. I was short of team-mates in the mountains – only Eric Caritoux was capable of staying with the leaders – so I roped in a bit of help from Fagor’s Robert Millar. He and I shared a manager, Frank Quinn, and his chances of winning overall were slim, so he was happy to help.

The BH team played their cards really well, knowing I couldn’t possibly chase them all. All I could do was ride as smartly as I could to make sure I stayed in contention.

After the short mountain time trial to Alto Naranco, near Oviedo, I was up to second overall but Cubino still led by more than two minutes. Worryingly, he was showing few signs of weakness.

* * *

The 13th stage, to the ski station at Cerler was make or break. It was then I knew I could win the Vuelta. Cubino finally cracked, although he kept hold of the yellow jersey. So too did Pino, but there was now a third of the BH riders to watch. Anselmo Fuerte leapfrogged me, pushing me down to third overall. However, I was only 33 seconds adrift.

I knew the race would be decided in the time trial but the Vuelta could be very unpredictable, as Robert Millar found in 1985, when he was ambushed by a Spanish coalition right near the end of the race, which cost him a certain victory.

Stage 16 to Albacete was a day to be wary. Every time we went to Albacete the same thing happened. It was like the wild west. The whole area was like a desert. The bunch would get about 30 kilometres from the town and the wind would pick up until the cactus plants and bushes were blowing sideways.

The crosswinds made everyone nervous but I was always quite comfortable riding in those conditions because it was just like the weather we had during the Belgian Classics.

It’s fair to say the Spanish riders were not so happy. They didn’t know where they should position themselves in the bunch so they were vulnerable.

The wind cut the bunch to ribbons. There were groups of riders scattered all across the plains and the crosswind was so strong it was almost impossible to close the gaps.

Fuerte managed to hang on at the front, but Cubino got caught the wrong side of a split. So Fuerte took the overall lead, making me even more confident of victory, because he was not going to match me in the time trial.

In normal circumstances, I’d have been certain of beating by Fuerte by the 22 seconds I needed in the time trial, but I didn’t want to take anything for granted. There was nothing technical about the course, so I just put it in a big gear and gave it everything. I beat Fuerte by almost two minutes and the Vuelta was mine.

Riding into Madrid on the final day with the yellow jersey on my back was a special moment. Louis Knorr, the boss of the Kas soft drinks company, was a cycling fanatic and he was very happy that I’d been able to win the Vuelta for him. Louis died later that summer, while we were racing the Tour de France, so I was especially pleased to have been able to win the Vuelta for him before he died.

Hunger, by Sean Kelly, is published by Peloton Publishing and is available in hardback.