Rudy Pevenage: If I wrote a doping book, it would be crazy

Former T-Mobile director talks about new autobiography but refuses to spit in the soup

Earlier this year, newsstands in Belgium and Germany were awash with headlines of Coca-Cola cans and milk cartons, of Ali Baba and discarded sim cards.

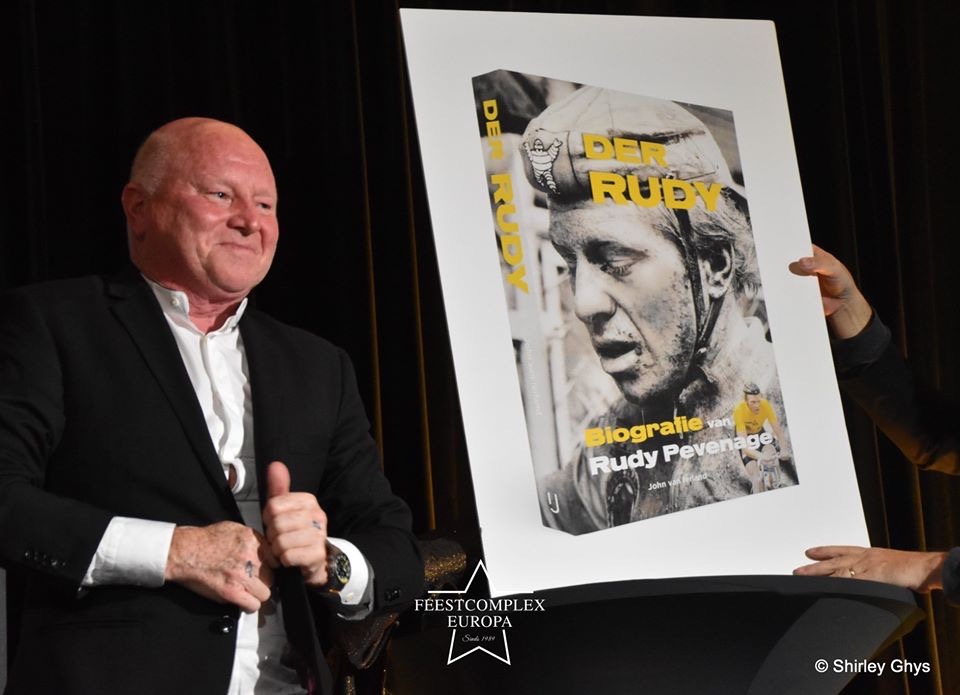

Der Rudy, the autobiography of Rudy Pevenage, was about to hit the shelves, unleashing seedy new details of professional cycling's doping decadence that were poured onto the back pages.

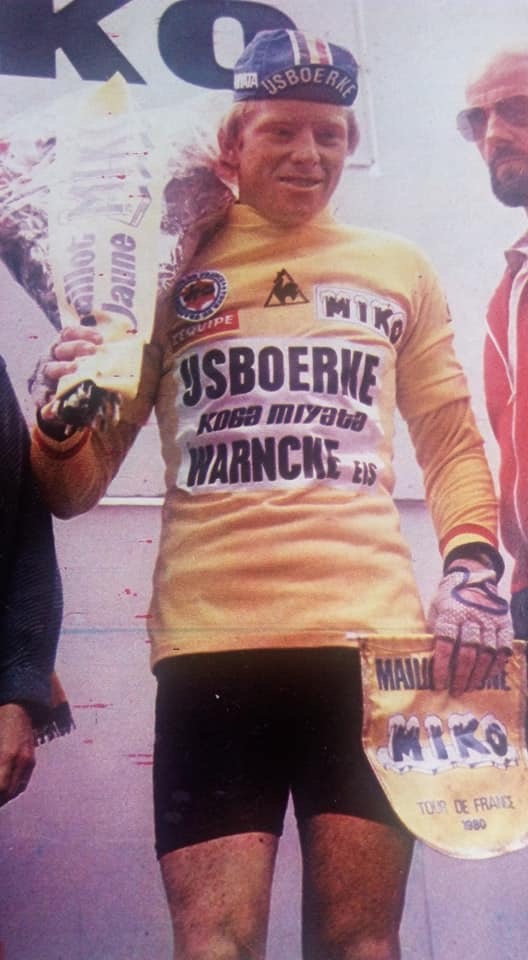

Pevenage is the former director of the Telekom/T-Mobile team and confidant of 1997 Tour de France champion Jan Ullrich. Pevenage's book tells the story of his life, from his childhood to his days as a professional rider and director, his struggles with divorce and cancer, up to his present days spent at his home near the top of the Muur van Geraardsbergen.

When the 65-year-old invited Cyclingnews into that home before the COVID-19 lockdown, it was clear the book he'd been meaning to write for more than a decade had caused him a fair bit of grief.

"I've had a lot of bad reactions," he says, shaking his head, before suddenly becoming animated and exclaiming in Flemish-accented English: "It's not a doping book!"

It’s a statement he'll utter repeatedly over the course of the conversation.

"The presentation of my book was a success, but one of the problems was that the Flemish press were given a preview, and they only took the two pages where I speak about doping.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"In Germany, they took only these two pages and they didn't even understand Flemish. The title they made was 'Rudy Pevenage kills Jan Ullrich' – because they didn't understand. And it's not true. It's not a doping book. It's a book about my story."

The 'two pages' he's referring to relate to those cola cans and milk cartons. The book reveals how Pevenage used a specially crafted double-walled can, with a top that twisted off and looked indistinguishable from a genuine sealed can, which could be used to hide Ullrich's medication. In the infamous San Remo blitz at the 2001 Giro d'Italia, he tells of how he left the can in the fridge, and his relief at nothing coming of his mistake.

The milk cartons in question contained blood bags and were couriered around Liège ahead of the 2004 Tour de France by a mountain biker nicknamed Ali Baba in a bizarre cast that also included Asterix and Obelix.

Pevenage had been the link between Ullrich and the disgraced doctor Eufemiano Fuentes, and ended up precipitating the Operación Puerto scandal as a call he made to Fuentes from his personal phone – he usually used pay-and-go sims – was tracked by Spanish police.

"The Coca-Cola can has nothing to do with doping," Pevenage says, looking to play down the explosiveness of his revelations.

"It was medication for Jan's allergic bronchitis, and there was a list of medication you could have with you. If they found me with it, I'd have problems, but it wasn't something that would be a positive test. The newspapers put, 'Rudy Pevenage had a can of Coca-Cola with doping [in it].' It was not true. It's a very big difference."

As for the milk cartons: "The story in Liège had nothing to do with Jan. Ali Baba came first, and then after a few days Asterix and Obelix arrived, then Eufemiano, for maybe 20 riders to make blood transfusions. He asked me to find a quiet hotel room, and I did, and I asked for an extra fridge because I knew he'd need it – I wasn't stupid. But it wasn't for Jan – it was for the other teams, for Rabobank, CSC, Liberty, blah blah blah. The book was misunderstood, especially because the Germans don't understand Flemish."

As a result of the media storm around the book’s juicier details, Pevenage has seemingly ruffled the feathers of a number of former riders and managers, many of whom are still involved in the sport in some capacity.

"He must keep his mouth shut," was the opinion of Eddy Planckaert, who appears as a pundit on Belgian broadcaster Sporza.

"I don't care," Pevenage responds. "There is no one who calls me and says, 'How is it possible that you say that?' Because they know it's all true.

"Omertà is there. I have no problem if Johan Bruyneel calls me or Lance Armstrong calls me or someone else calls me, and we can discuss it. But they will not call me, because they know I am right. They were all in the same boat.

"I cannot finish my book if I don't mention these things. The blitz of San Remo, maybe it cost me two years of my life, with all the nerves and stress. I have to talk about it. But I didn't write a doping book. If it was a doping book, it would sell three times more, with everything I know. If I made a doping book, it would be crazy."

The obvious question is, having highlighted the omertà that still governs the past, why doesn't he write a doping book?

"Because I don't want to. I have a lot of friends in cycling," he says, referencing those who have participated in his 'Champions Cycle Tour', which has helped raise €18,000 for cancer charities in Belgium.

"LeMond, Bettini, Bugno, Museeuw, Van Petegem, Van Impe have all been here. All these riders who were here to help me… I don't want to fuck off these friendships.

"Maybe some of them do have a problem with this book, but that's no problem, because I didn't write a doping book."

Doping at Telekom – 'no other choice'

If Pevenage were to write a doping book, it's difficult to imagine how it might look. There's no attempt to deny he cheated – both as a rider and a director – but there's certainly an incoherence in the way he frames his sins.

One the one hand, he seems to concede he and his colleagues fell into the same vices as everyone else. And yet, on the other, he works hard to establish a moral relativism where, even if there are no saints in this story, some sinners are holier than others.

"No," he says, when asked if he harbours any regrets.

"During that time, you didn't have any other choice. You have a big sponsor and a big rider who is paid to win. If you have the competition who are doing some things, what do you say? 'We don't do it?' Then you have no results, and the sponsor says stop. Or you say, 'You have to do like the other guys.'"

However, Pevenage elsewhere insists that Telekom weren't "like the other guys", painting a comparison between them and the likes of Lance Armstrong that serves to effectively exonerate them of any wrongdoing.

"When [Bjarne] Riis came to our team, he'd come from an Italian team, and he said: 'Here it's the kindergarten – you are living in the kindergarten,'" Pevenage says, laughing.

"We had our own tests from 1998-2001, because the German federation didn't have the money to make all the tests. T-Mobile, our sponsor, paid this organisation to test ourselves, at the same time that our rivals were training in Colorado and taking EPO."

Referring to the donation made by Armstrong to the UCI in 2002, and the allegations that he received preferential treatment in return, he adds: "Somebody knew when the tests were coming. Our American friend buys some machines for the UCI and hey, 'Fuck you.'"

As such, Pevenage seems to echo Ullrich, who confessed to doping but not to 'cheating'.

"I'm still sure that I was a good sports director – otherwise you cannot win all those stages or green jerseys with Zabel, the Tour with Ullrich, the Tour with Riis, the podium at the Olympics, the two time trial world titles with Jan," he says. "I'm proud of it and I can say what I want."

'Nobody helped Ullrich'

While Pevenage's book has angered some of his contemporaries, it has also created a rift between him and Ullrich – a relationship that had stretched well beyond the normal parameters of a director and an athlete.

Ullrich retired in February 2007, not long after his involvement in the Operación Puerto scandal came to light – although he would only confess to doping some six years later – and he has not found life after cycling straightforward. His descent into the vices of drink and drugs was well documented in 2018, although he has since made considerable steps along the road to recovery.

"I know he was a bit upset about it [the book], and angry about the mistranslation," Pevenage says. "Normally, he would have come to the presentation, but because of the German press, he decided not to. What did the German press do for Jan Ullrich? They killed him, like they always kill.

"My relationship with Jan will never die. We have done too much together – good times and bad times. Now maybe with his new friends, I heard there are people telling him that it's better he doesn't talk to me. I don't know."

Pevenage spoke to Ullrich over the phone recently, and last saw him September. He says he's doing much better and is considering returning to what he initially did in retirement – making guest appearances at Gran Fondos and other events for hobby cyclists.

"I think still that Jan can be the image of a brand. Adidas, Pinarello, Nalini, or something," Pevenage suggests.

"Why not? Jan Ullrich is not a businessman, but that's my idea, and it's possible, because you go to Italy and Spain and everyone asks, 'How is Jan ?' They don't care about the doping; they want to see Jan. But I don't think he wants to come back to pro cycling. It doesn't interest him, and I find that okay."

Part of the reason Ullrich has no interest in returning to the world of professional cycling is he felt so burned by it. Whereas many of his fellow former dopers have found other roles within the bubble, Ullrich has remained something of an outcast.

"Nobody helped him when he had his problems," Pevenage says, taking another swipe at Armstrong, who, at the height of Ullrich's tabloid-documented troubles, flew to Germany, saying he'd do "anything in my power" to help.

"I don't believe Armstrong came to Germany to see Jan. It was for his own profit, to stay in the picture. Jan went to America for a week, but not with the person that Armstrong proposed to him. Armstrong went to Germany and said, 'Ah, I'm here with my private jet.' But it was for his own image, not to help Jan."

'Ferrari is still working on Teide'

With the ghosts of cycling's past still looming large, we ask Pevenage if he thinks cycling has cleaned up its act.

"I think it's very clean. I don't know, but it cannot be like before," he says.

This statement, however, is tempered – if not outright contradicted – by the assertion that the doctor Michele Ferrari, who was behind much of Armstrong's doping, is still at large, despite his lifetime ban.

"I don't know what Ferrari is doing but I know he's still working. Fuck him," Pevenage says.

"I know that Ferrari is still working in Tenerife, on [Mount] Teide. Normally, they have to know it also. I know it, and I have nothing to do with cycling. Testarossa. They don’t say Ferrari now; his name is Testarossa.”

His comments come just weeks after Astana riders Jakob Fuglsang and Alexey Lutsenko were linked to Ferrari, although the Cycling Anti-Doping Foundation has since ceased its investigation with no sanctions for the riders, who both denied the links. Likewise, Ferrari himself strongly rebutted the allegations.

"It doesn't interest me why he is there. I know he is working," Pevenage says. "Maybe riders now use little doses where even in the blood passport it's not possible to see it, or to say you did it."

Pevenage makes the point that "elite sport is about money" and the incentive to dope will therefore inevitably persist, but he also argues that cycling is "the most tested sport".

"In tennis, if someone is positive, they put them six months injured. You think footballers, the best players who are paid millions, if they have a little injury that they can get over it with a bit of cortisone, you think they don't do that? In the Tour de France, if you have a bee sting and you need cortisone, you can go home – it's over. Why a specialist from the UCI can't come and see, 'OK, he has this problem; we'll give him cortisone for two days...' What a fucking system!

"I have nothing against other sports. The only conclusion for me is that cycling is the most tested sport, but there is still this omertà. You cannot speak about anything."

Emphasising his point, he insists that Fuentes – whom he still considers "a friend and a good doctor" – will never reveal the names of his clients.

"I know personally of 20," he adds, "but it doesn't interest me to say who they are."

Rudy Pevenage did not write a doping book, but he could, but he won't.

Patrick is a freelance sports writer and editor. He’s an NCTJ-accredited journalist with a bachelor’s degree in modern languages (French and Spanish). Patrick worked full-time at Cyclingnews for eight years between 2015 and 2023, latterly as Deputy Editor.