Roger De Vlaeminck's cycling Dream Team

Classics legend picks teammates for the cobbles, the hills, and for spying on Merckx

Earlier this year, during the so-called 'Opening Weekend' of the Classics season in Belgium, Cyclingnews sat down over lunch with Roger De Vlaeminck near the farm where he lives in Kaprijke.

The 72-year-old, known as 'Monsieur Paris-Roubaix' for his record four titles at 'The Hell of the North', is one of the most successful Classics riders of all time, and one of only three to win all five Monuments. He spent much of his career on Italian teams and, as well as the numerous one-day victories, he also won 22 stages at the Giro d'Italia and six overall titles at Tirreno-Adriatico.

Here, he picks his 'dream' squad from riders he rode with in the 1970's and 1980's, balancing his most loyal teammates with his own individualism, and recounting the highs, lows, camaraderies and controversies.

The Rules

- Dream teams must feature eight riders, one of which can be the rider selecting the team – in which case they pick seven riders to join them.

- The riders picked must have all ridden with the person picking the team. That means you can't just pick the seven or eight best riders of a generation

Roger De Vlaeminck - team leader

I'm picking myself as the team leader. You might expect me to pick Francesco Moser, but we were too similar, so there's no room for him here.

It's hard to pick a team to support me, because I was never overly reliant on domestiques during my career. A lot of the time, I was just by myself. You need domestiques if you have a puncture every now and then, or to chase down a group, but a team leader has to know for himself where to ride.

In my relationships with my domestiques, I was a man of few words. I never really had to explicitly ask for riders to work for me – they kind of did it automatically. If you can do a lot by yourself, you don’t have to ask for a lot. I was easy going, just as I am today.

I wouldn't really speak to teammates before the race, or discuss things in detail with the director. There's no such thing as tactics in bike racing. Well, there are, but what I mean by that is, if you're strong enough, tactics don’t really matter. You know who reads races well? Riders who are strong.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Herman van der Slagmolen - Classics domestique and spy

Herman is easily the first name on the team-sheet. We met at Flandria and then rode together at Brooklyn and Sanson. There were a few guys I used to take with me when I moved teams, and Herman was one of them. He was the closest and most loyal. As a rider, he suited my needs. I always say I was able to be in the front by myself, but if he was by my side it was always a little easier.

Herman would have a very specific role in the Classics. He was the guy who could go fastest for two kilometres, so it would be his job to lead the peloton in the last two kilometres before the Kwaremont, or whichever section opened up the finale. He excelled on the flat but was not so good uphill. In Paris-Roubaix, he was formidable, and was super important for all the Classics.

Herman also had a secondary role; he was kind of my spy. When we were in a hotel, I would send him to go and see what [Eddy] Merckx was eating and drinking. I would get him to pat one of the teammates on the back and strike up a casual conversation, but out of the corner of his eye he had to register what Merckx was eating and drinking. We did this with [Felice Gimondi], too. I wanted to know what the best guys were doing. With Merckx, it was always water. I used to drink cola sometimes but it can bloat the belly. After his assignments, Herman would report back and it was always the same: "Only water."

Ronald De Witte - All-rounder

In the Classics, I’d have a team of only domestiques, but for uphill races, De Witte would be an important rider, and could be a co-leader. He was very strong uphill, and he was also quite capable on the flat. He could win races in his own right and showed it at Paris-Tours when he was in a break with [Raymond] Poulidor.

Ronald actually got me in a lot of trouble once. It was the 1976 Giro, we had Johan De Muynck in the team, who won the Giro two years later. In one sprint finish, I crashed and had a haematoma on my leg. The next day, I was able to finish, but I was in a lot of pain. The following day was a mountain stage with four big climbs, and I abandoned on the first climb. It was a huge issue in Belgium because the story was that I didn’t want to support De Muynck, because he’d become the team leader and I couldn’t deal with him leading the race. Fred De Bruyne, the TV commentator, fueled this controversy, and the fact that De Muynck lost the Giro made it an even bigger issue. De Muynck’s wife called me a traitor – it was on the front page of Het Nieuwsblad. It’s something that lives on today. De Muynck only lives around five kilometres away but we do not speak.

Anyway, the true culprit of the story is Ronald De Witte. You see, later on the stage where I abandoned, he abandoned too. He had sand in his eyes, and he's been known as 'The Sandman' ever since. I don’t blame him for abandoning, but I took a lot of heat because of it. My abandon had nothing to do with not wanting De Muynck to win. I had an injury. I was leading the sprinters’ jersey by 100 points, so why would I abandon? But when De Witte left as well, it looked bad. Had he stayed in the race, it would never have been such a big issue.

De Witte was a very clever guy, with good business instinct, but in this specific incident he was stupid – the one time he was stupid. That said, I still want him in my team.

Patrick Sercu - Sprinter

I could win sprints but I would like an extra sprinter for my team, and it would be Patrick Sercu. He’s the fastest guy I’ve ever known. He had this incredible leg speed from the track and would always ride a smaller gear than me. His acceleration was unbelievable – he could take three or four metres in a couple of seconds.

Patrick was the middle man for my transfer to Dreher in 1972 and then we rode together at Brooklyn. It’s incredible how many times we came first and second in a race. No one would lead the other out; we’d just both sprint. There was no rivalry – that’s just the way we did things. The team was focused on Italian races so there wouldn’t be multiple programmes like nowadays, where you can spread sprinters out. I don’t see a problem with it at all. If you sprint with two, you double your chances, and that’s how it can be in my dream team.

Patrick was a nice guy but he was easily wound up. I remember he used to wear this woolly hat, and if it rained he would get so upset with the rain. I still see this image of him, at the end of a race, throwing this soaking, heavy hat to the ground furiously. In the Giro once, Moser had to take a shit during the race, and did it into a cap. He then threw it away but it went into the middle of the bunch and it hit Patrick. There wasn’t a lot he could do because there was a climb coming up but after the race he certainly had words.

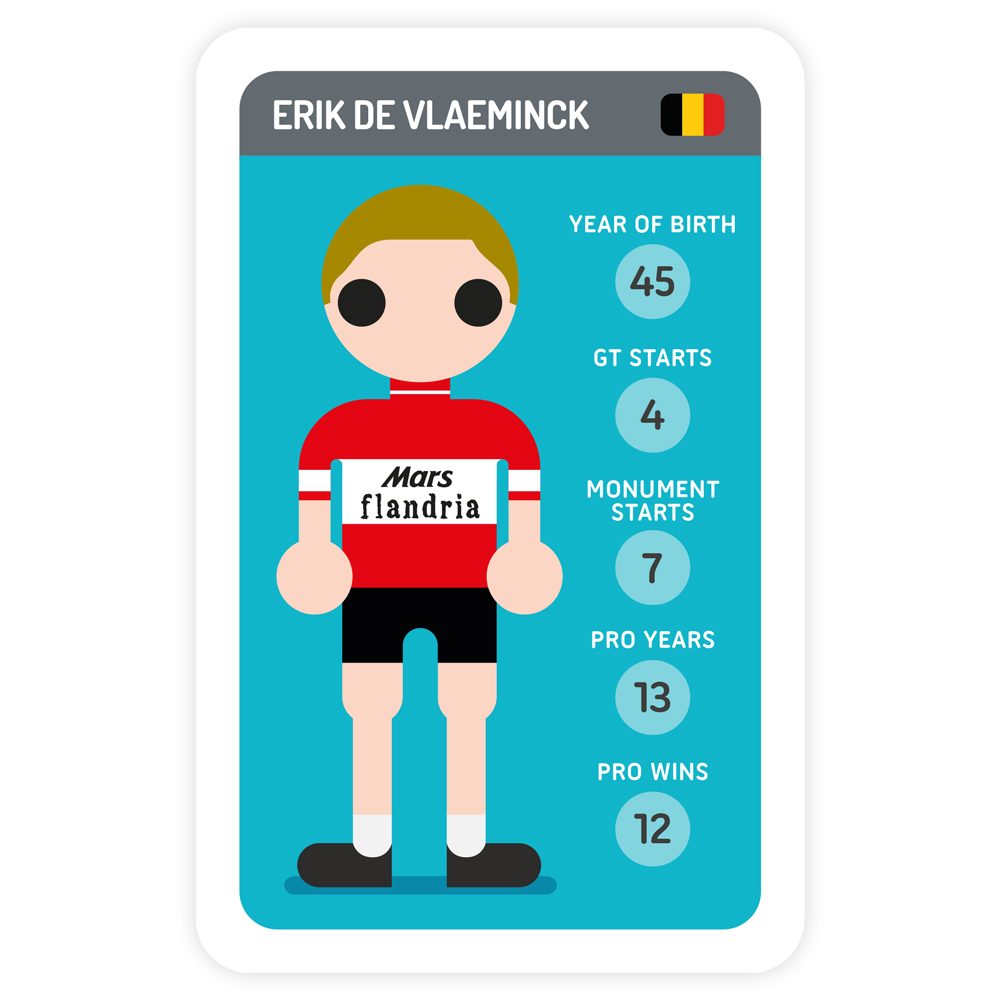

Eric De Vlaeminck - Free role

I want my brother in my team but I’m trying to find a role for him. Maybe he can have a free role. When we were racing together, he never really had to work for me anyway.

Eric would do the Spring Classics. He had the same characteristics as me but in road racing he was a bit less talented. He couldn’t deal with the stage races and Grand Tours in the same way but if you ride 40 cyclo-cross races over the winter, then the Classics season is enough. He’d be in the finale in Roubaix and Flanders.

As brothers, we were very close. Growing up, we shared a bed, farting against each other’s legs, as brothers do. We lived in a rural area and we’d ride through the fields, all day long. There were these fences with barbed wire, and Eric would jump over them so easily. One time a farmer’s dog chased us, and Eric was able to get away but I got bitten.

He was very acrobatic on the bike. His handling skills were excellent. He could ride a long way on a single train track. It’s something we’d do as a little contest. I always looked up to him as an older brother but also as an athlete. He could have been a champion in gymnastics as well.

He showed it when I won Liège-Bastogne-Liège. There were six of us in the front, and me and Merckx kept attacking each other. He’d go away, I’d counter and go over the top, then he’d come back and go away. After a while, we slowed down and the group came back together again and were riding to the track in Liege. We had to go through this very narrow tunnel, only two metres or so wide. I was on the right, Eric was next to me, then Merckx was on the left, shoulder-to-shoulder, in the space of two metres. I said to my brother, 'go to the left', and then I attacked.

Again, there was a lot of trouble from this manoeuvre, but Eric can ride wherever he wants, and he didn’t have to do a big move, just something subtle and then I could go away on the right.

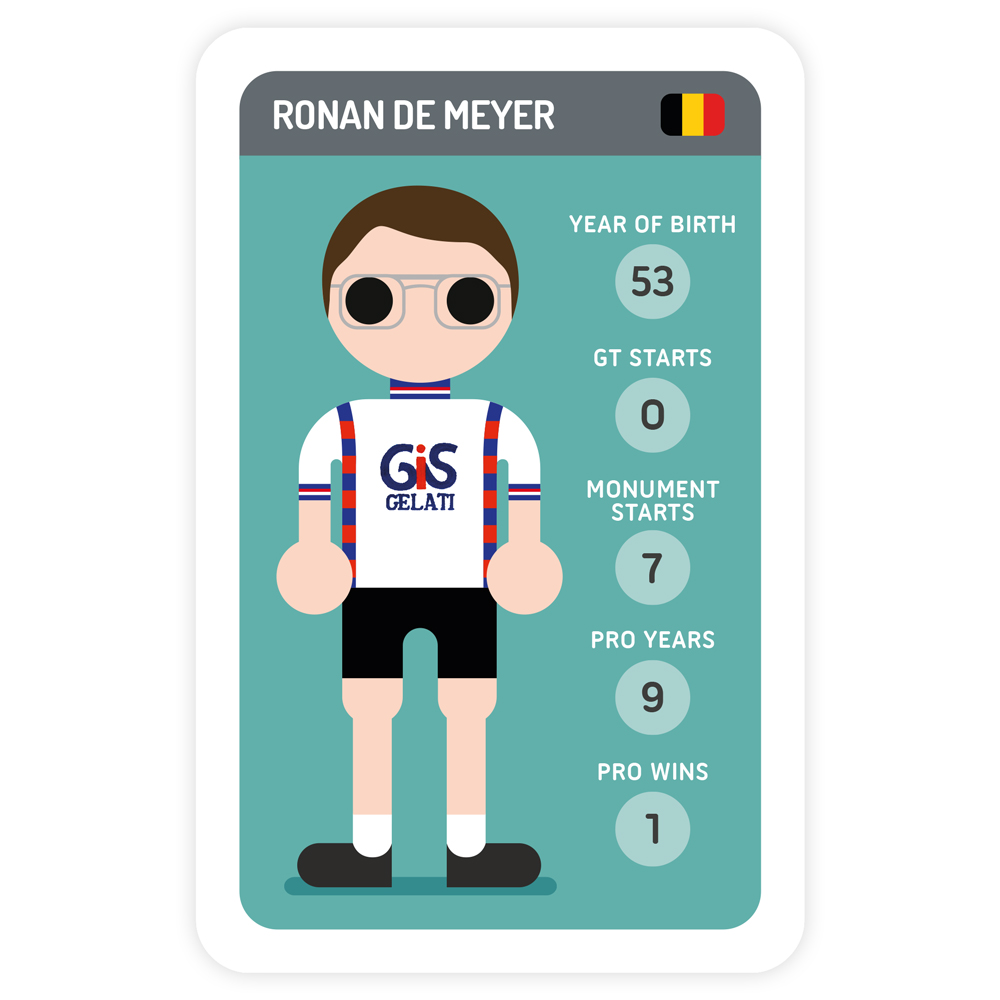

Ronan de Meyer - Flat domestique, joker

Ronan would be the guy for the jokes and the atmosphere. If he said something, it was always funny. 15 years ago, I had a TV show where I coached Zimbabwean riders, and Ronan was on that show as well because he added a bit of humour.

After Tirreno-Adriatico with Brooklyn one year, we rode an extra 180km back to the hotel in Rimini after the final time trial. It was a very hot day, so I told Ronan to just ride without a jersey on, and he did. My skin is ok with a lot of sunshine but when we reached the hotel, he was completely pink. He went to his room and was shaking in his bed. He was a total mess. He wasn't necessarily the one cracking all the jokes, but when Ronan was around you'd be guaranteed laughs.

He was not what you’d call a super-domestique but he always did what he had to do. He was only really good on the flat, so in Italy he wasn’t always super useful, but he’d be the guy for thee first 100 kilometres. If it was a hilly finale, he’d work on the flat in the first part of the race – a bit like Tim Declercq now for Deceuninck-QuickStep.

Attilio Rota - Climbing domestique

Attilio was the strongest Italian I rode with and he was my man for the very long climbs. Whenever I missed an attack, for example if Merckx went away and I didn’t respond immediately, Attilio could close the gap and would ride until he was totally cooked.

He was the best domestique I had in Italy, ever. He’d be by my side from the start to the finish. The only time he wasn’t by my side was if he was on a toilet break or if he went to get bottles. His own performance was irrelevant to him. I’d often say, 'Attilio, ride your own race today', and he’d say, 'No, I won’t'. He was the most loyal, most gentlemanly teammate I’ve ever had. He had all the good qualities.

All the other teams wanted to sign him, because he was so reliable. In order to keep him in the team, I would often give him some extra money. You can ask my foreign teammates; I was generous financially as well. I was mindful that riders who didn’t win themselves deserved a bit extra. For someone like De Witte, who could win races by himself, this would not be necessary, but in the case of Attilio, it’s important, as a leader, to give a little extra now and again.

Stefano Giuliani - Climbing domestique

Like Ronan, Stefano was a very funny guy, and, like Attilio, he was a good climber. He was around when I rode with Moser, and actually he was more linked to Moser, but we were often roommates, and I had all the fun in the world with him. His impersonation of a monkey was famous.

As a rider, he was strange. He was good uphill but terrible on the flat. At Sanson, we were one of the first teams to use heart rate monitors, and we’d do these exercises where we’d have to stay just out of the red zone. My heart rate was 165 before I went into the red, and Moser was a top performer as well. Stefano, on the other hand, would be in the red riding at 36km/h with his heart rate at 130.

He would be useless in a time trial or team time trial, but he’d be a very good uphill domestique in my dream team and, as I said, he’d be a real character.

Patrick is a freelance sports writer and editor. He’s an NCTJ-accredited journalist with a bachelor’s degree in modern languages (French and Spanish). Patrick worked full-time at Cyclingnews for eight years between 2015 and 2023, latterly as Deputy Editor.