Robby Ketchell: Garmin-Sharp's secret weapon

Winning means planning and analysing to the nth degree

This article originally published on BikeRadar

Garmin-Sharp's upward trajectory has included a team time trial win in the 2011 Tour de France, an even more dominant performance at this year's Giro d'Italia with another team time trial win plus the overall victory with Canadian Ryder Hesjedal.

While time trials arguably remain the ultimate test of pure athletic prowess, Garmin-Sharp's sports scientist Robby Ketchell has broken it down into a complex – and in some sense, predictable – equation.

Ketchell began his aerodynamics work in 2008 at the Colorado Premier Training wind tunnel in Fort Collins, Colorado, where the team then known as Garmin-Cervélo conducted most of its drag testing. Ketchell eventually became a full-time employee of the team and has been on staff for the past 2 ½ years.

Wind tunnel testing yields mountains of data but instead of drowning in it, Ketchell wholeheartedly immersed himself in it, ultimately breaking down the physical nature of time trials into a mathematical algorithm. According to him, Garmin-Sharp's particularly notable success in team time trials is no accident.

"There are nine guys out there instead of one so everything is increased by nine-fold," he told a group of journalists gathered for Mavic's recent Cosmic CXR 80 launch in Geneva, Switzerland. "Everything from equipment from the sponsors and their preparation, from the riders' preparation, the mechanics, soigneurs, the directors, everything – there's so much that goes into it."

Don't discount the gear

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

According to Garmin-Sharp sports scientist Robby Ketchell, these days the most significant gains are made through equipment

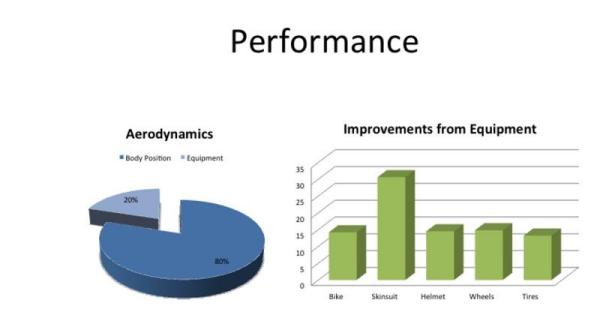

Ketchell himself admits that the rider produces the bulk of the total aerodynamic drag – roughly 80 percent, in fact. But while common sense would then suggest that rider position should be the main focus in the wind tunnel, Ketchell says the opposite is true. Given the UCI's increasingly stringent rules regarding such minutiae as arm and saddle angle, equipment optimization has actually increased in importance, particularly for time trial specialists whose positions are already highly refined.

"Equipment is really where we can pick and choose and make sure we have the right bearings, make sure that crank length is correct, make sure wheel and tire choices are right, handlebar and water bottle placement, everything," he said.

According to Ketchell, the five most important equipment categories are the frame, clothing, helmet, wheels, and tires, with nearly 30 percent of recent gains coming from the team's latest skinsuits on account of the enormous surface area involved. The other four categories in total combine for another 50 percent or so with other smaller factors filling in the remainder.

Weatherman Ketchell: "Today in Cleveland…"

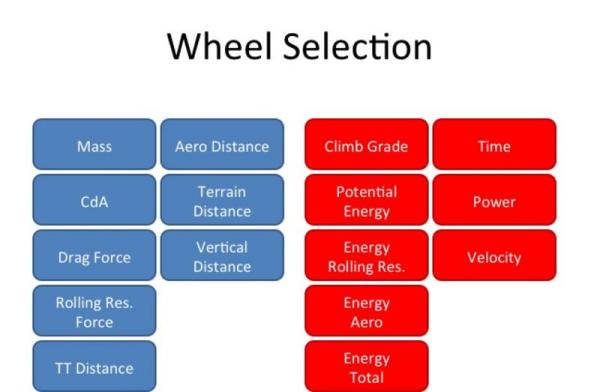

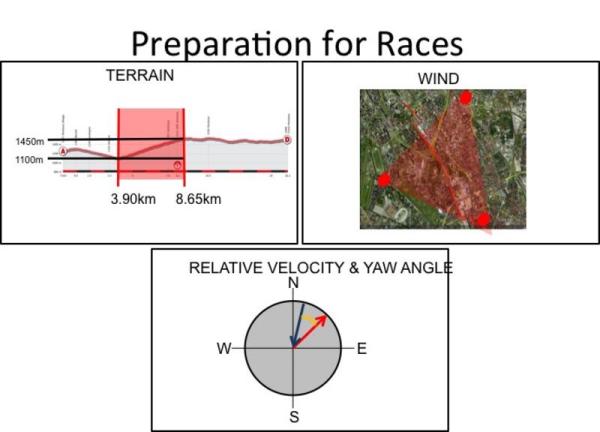

As do most top teams, Ketchell previews key courses firsthand – he drove the time trial course in Milan three days prior at 2am – but his preparations go far beyond that. Naturally, he didn't reveal to us his exact formula but even just a brief overview of some of the terms involved is enough to blow your mind: the exact course profile, wind direction and speed, air density, percent gradients, aerodynamic drags of various components, rolling resistance, potential energy, total energy expenditure, rider and equipment weight, and more.

Ketchell doesn't just look at recorded wind data from those previews or weather forecasts. He studies historical weather patterns – from the past thirty years – from nearby weather stations in an effort to predict the wind directions and speeds at the exact time a rider will be on course.

"We find weather stations throughout the world, create a triangle around the course, and collect data from the past thirty years leading up to the time trial," he said. "We look at within one month the race performs and we look within the timeframe that the race is taking place and we calculate what the air density is going to be, what the wind speed will be, and what the wind direction will be. From that information we can apply correction factors based on the area we're in such as a city versus coastal region."

Even rider size is factored in – after all, a bigger rider is less affected by crosswinds and can usually handle a deeper wheel. Assuming no unusual circumstances, Ketchell can predict finishing times. If information can be gathered at the beginning of the season, he can actually go to the team's sponsors and request specific equipment ahead of time.

"Trust the math"

Ketchell's distinctly scientific approach has occasionally dictated equipment choices that went against the grain. For example, key riders such as Christian Vande Velde used a specially prepared Cervélo R5ca for last year's USA Pro Cycling Challenge time trial instead of the more common full-blown aero rig. Conversely, the team used time trial bikes for this year's Tour of Romandie time trial while many others selected road bikes.

Ketchell admits he occasionally encounters some resistance to his suggestions but history has worked out in his favor and with such narrow margins these days, even the slightest edge can be significant: Garmin-Sharp (then Garmin-Barracuda) won its Tour de France team time trial in 2011 by just four seconds; the Giro d'Italia one by only five.

"Trust the math," Ketchell says, and now more than ever, the equations are working out in Garmin-Sharp's favor.