Retirement chronicles: When Philippa York met Nicolas Roche

'If everyone is telling me I’m too old, then maybe I should realise the sport is changing and I should look at other things' say Irishman

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The professional bike rider has, to some extent, a say in how they arrive in the paid ranks but at the end of their career, that’s usually far from the case. For some, like Alejandro Valverde, time seemingly goes on forever whilst for others, they fade gently into the past having retained a certain amount of dignity and happiness.

Ideally, as a rider, you want to exit the sport with few regrets, a limit to your mental and physical scars, and some kind of future waiting for you. In a normal job that would mean a leaving party with balloons and a gold-plated carriage clock for the mantlepiece, but in the cycling world just leaving nicely is often more than enough.

At the recent Rouleur Live event in London, I got the chance to sit down with three retirees to talk about their experience on leaving the WorldTour and navigating their futures. First up, Nicolas Roche.

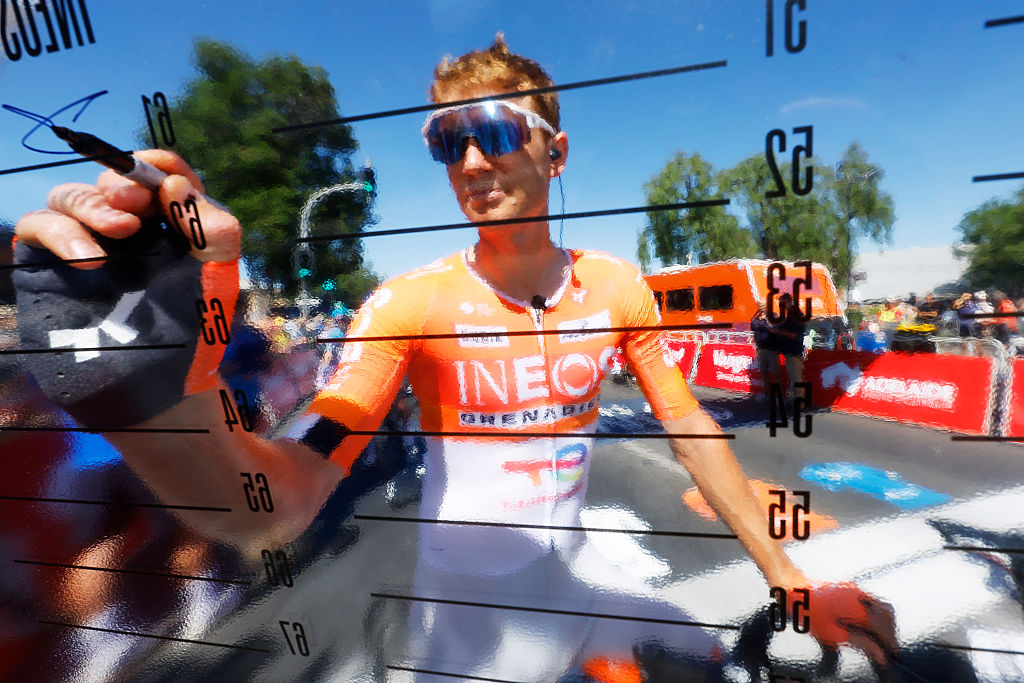

The 34-year-old Irishman had a long and successful career that spanned three decades and a number of the biggest teams in the world. He won stages in Grand Tours, had top-10 finishes in the Vuelta a España, and worked alongside and for some of the biggest names in the sport including Alberto Contador and Chris Froome.

In this exclusive interview, Roche opens up about the tough moments that led to his retirement, how the sport has moved without him, and his future.

Philippa York: What made you decide this was going to be your last year?

Nicolas Roche: It was a really tough one, and it wasn’t a clean call. It had been in the back of my mind since July, and at the Giro I felt I was still competitive and was thinking maybe I could do another year or two. I was enjoying riding and felt competitive but the long period between the Giro and the Olympics was two months without racing and then I learned the team wasn’t going to resign me. It was a bit of a shock. Suddenly that changed how I saw the next year.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

At first, I wasn’t too worried but when I called other teams they said age was the main problem. Eight times out of ten we never talked about salaries. Usually, it was just about how they were investing in young guys.

PY: Do you think it could be partly down to everyone looking for the next big rider?

NR: Everyone is afraid about missing out on the next [Tadej] Pogačar or Remco [Evenepoel] but they’re going to be there for a while so good luck to the new 19-year-olds. They have some challenges ahead. The team felt they didn’t need me. They said I had too much experience, but it wasn’t the type they wanted. I had the knowledge they needed but they didn’t necessarily need my opinion, which I would sometimes give. They wanted someone to follow their ideas without any questioning.

PY: From my experiences that isn’t always what Dutch teams want to hear, how did that work out?

NR: In the races I always did as I was told but I always asked why. That became a problem. It doesn’t always go down too well in some teams so there was a conflict because DSM work in a very specific way, and I’m not saying it’s right or wrong, but they have a plan and they stick to the plan.

I was brought up trying to win races or help others to win races and sometimes it wouldn’t fit because I’d be reading the race to get the best result whilst sometimes DSM would be focusing on some kind of protocol. For example, getting the lead-out right regardless of the result, where sometimes that just didn’t work for me. I’d think maybe we can miss one guy from that lead-out and get a better chance for him.

They had a very specific way of working. I was very much performance orientated and not just following a process. When I went to a bike race I was thinking about winning it because that’s how I was brought up, and I was competitive. The whole strategy was about following the process and I didn’t fit in with the management because they said I was asking too many questions.

PY: So this performance process was sometimes more important than the result?

NR: The ideology was regardless of the riders you have, if the process was right then it was always repeatable. Having been in some of the best bike teams I was used to winning.

PY: Did having your opinion or view maybe influence the decision not to keep you?

NR: Things like asking early on in my time with the team why were we doing altitude training camps that were 23 days long whilst everyone else was doing 15 or 18 days, was maybe not seen as a good thing. That was seen as questioning the strategy, but I was just curious as to why. Was there a specific reason? I thought I had a good relationship with the young riders and they were appreciative, saying I’d made a difference when they raced with me. I would give them some of my knowledge and experience that I’d accumulated over the years because that’s where I got my satisfaction.

At first in my career, I got satisfaction from winning, then from helping GC guys win, and then from helping the young guys progress. There were different steps in my career, and I went through each role. I know that DSM have had a lot of stick in the media with guys leaving but they’re actually not a bad team. I wanted to stay there so I was disappointed they weren’t keeping me.

PY: Didn’t that cause you to think it might be time to move on and retire?

NR: There was a moment where I felt it would be difficult to get offers from different teams, and I did get offers, but that caused me to question was this, maybe, the moment. If everyone is telling me I’m too old, then maybe I should realise the sport is changing and I should look at other things.

I did Eurosport/GCN commentary at the Vuelta 2018 and loved it. I absolutely loved it and I’ve been doing that every year since. This year, I went directly to GP Plouay from doing commentary, at end of August, and when I woke up on the morning of the race and I felt that I didn’t want to be there that was the first time that I felt I didn’t want to be there. I was always looking forward to racing.

I was fed up with all the calls, the negotiations, the racing, other little things but there was a moment when the racing wasn’t enjoyable. I still wanted to ride my bike but I was tired of the stuff outside the racing. I had more fun doing the TV stuff than the last few races and realised that was something I would like to do if given the chance. I’ve nothing confirmed but I’ve had approaches, and that’s exciting because I liked doing that. I got personal satisfaction from being involved in that.

PY: How has this season been now that racing has recovered slightly from the 2020 restrictions?

NR: Racing has changed dramatically since Covid. Every race has been like it might be the last event. There seems to be no tactics, no energy saving. I got used to it but I got fed up with being told by 25-year-old sports scientists just out of university that I’d been making mistakes all my career, that my training was wrong, and I needed to do more of this type of training or less of that.

It seems a small thing but I didn’t like that and the phone calls asking why haven’t stuck to the training, because with the change to young riders also came with younger trainers, sports scientists and directors. They’ve arrived with their revolutionary ideas from a textbook but I’ve been trained by some of the best people in the business and have figured out what works for me. That cracked me a bit this year, making my training more complicated but it didn’t suit me.

PY: Were the final races difficult?

NR: The hardest bit was in between when I’d decided I was stopping. The TV thing made me realise there was more to cycling than just the racing. During Covid, as long as the Tour de France happened I was OK but I gradually realised that there was other stuff outside of the sport. Cycling was a big part of my life but a small part of life.

PY: The biggest fear for a lot of people is about what to do next.

NR: I have a lot of options but which one to choose, some might conflict with timing, so although I’m not spoiled with offers I’ve also created my own choices. Investment in a bike shop in London, a couple of restaurants, a bike shop in Ireland, and I’m trying to open a second one there.

I have a lot of projects already built so I was ready when I stopped but there’s the question do I want to do TV? Also, do I want to work with a team, not as a sports director because that would be the same conflict position as when I was racing because most of the time is looking a GPX files in the briefing, going over road furniture, corners, roundabouts, etc., than talking about the actual race?

PY: Will you miss the excitement, the ups and downs of competition?

NR: I jumped out of a plane last week so I definitely have a bucket list of things. I know I’ll need some competition, I’ll need the excitement. I’m still doing one to two hours of exercise a day but I realise that I’ll miss the highs and lows of racing.

As a pro bike rider, every day has been different, and I realise that I won’t have that. I’m not saying I’m not afraid of that but realising that is a start. The difficult moment will be when I start seeing training camps in December. That’ll be hard, however, I have something coming up early next year which will take me out of my comfort zone and challenge me.

Philippa York is a long-standing Cyclingnews contributor, providing expert racing analysis. As one of the early British racers to take the plunge and relocate to France with the famed ACBB club in the 1980's, she was the inspiration for a generation of racing cyclists – and cycling fans – from the UK.

The Glaswegian gained a contract with Peugeot in 1980, making her Tour de France debut in 1983 and taking a solo win in Bagnères-de-Luchon in the Pyrenees, the mountain range which would prove a happy hunting ground throughout her Tour career.

The following year's race would prove to be one of her finest seasons, becoming the first rider from the UK to win the polka dot jersey at the Tour, whilst also becoming Britain's highest-ever placed GC finisher with 4th spot.

She finished runner-up at the Vuelta a España in 1985 and 1986, to Pedro Delgado and Álvaro Pino respectively, and at the Giro d'Italia in 1987. Stage race victories include the Volta a Catalunya (1985), Tour of Britain (1989) and Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré (1990). York retired from professional cycling as reigning British champion following the collapse of Le Groupement in 1995.