Remembering Poulidor and his enduring presence at the Tour de France

Frenchman attended every edition of the race since 1962

Finding Raymond Poulidor on the Tour de France was never difficult. You simply went where the fans were. Pretty much every morning, Poulidor could be found in the village départ, holding court at the Crédit Lyonnais stand, signing autographs and catching up with old friends. He was a difficult interview, largely because people never left him alone.

Justifiably, he was described as the most popular cyclist in France, and he won hearts in a way that only Fausto Coppi might match. After retirement, if he drove the Tour route, the applause was always effusive among the murmurs of, 'Poupou, voilà Poupou'; so, too, each day when he arrived at the finish.

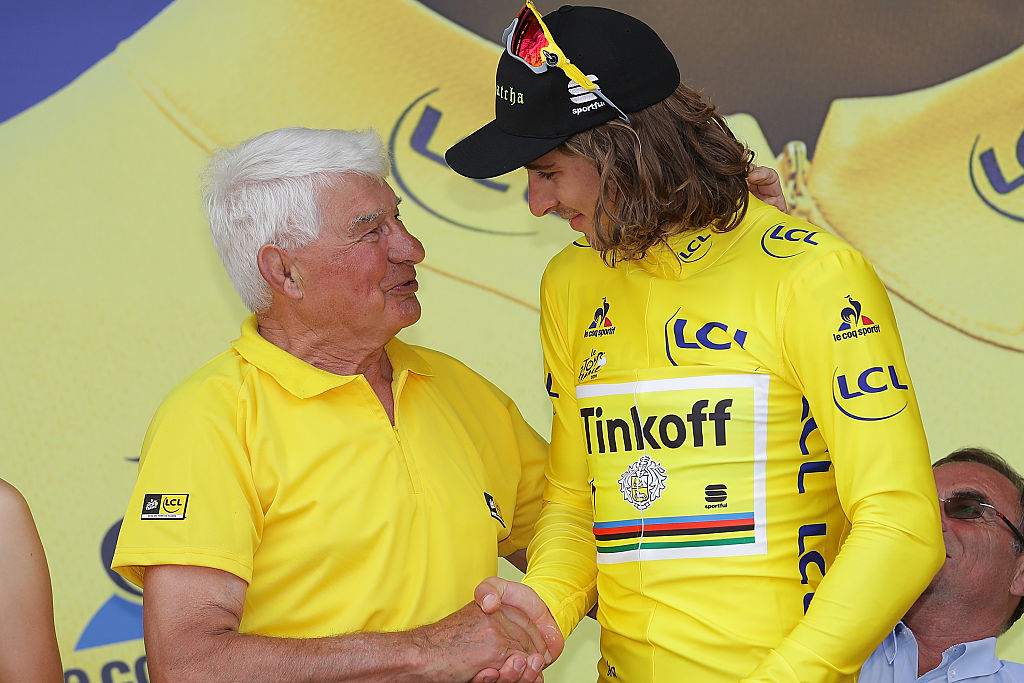

The deliberate irony always made me smile: the man who was celebrated for never wearing the yellow jersey earning good money in retirement for publicising the jersey's sponsors.

Even this year, as his health failed him, Poulidor was still that presence on the Tour. As he said in 2016, he couldn't imagine his life without it. And, after his death, this is where most people within cycling will miss him: he had been on every race since his first start in 1962, which means that by the end of his life he predated pretty much everyone else. No one in the caravan had been on a Tour without Poulidor being present.

For that reason, he will leave a far larger gap than a bevy of greats who boasted far more distinguished race records, although here it should be noted that Poulidor was a successful rider, especially in his early career. In the modern era, most cyclists would hang up their wheels contented with a palmarès that includes a Vuelta a España (1964), Milan-San Remo (1961), seven Tour de France stage wins and over 150 other victories.

Poulidor's Tour de France record of 12 finishes in 14 starts, with a lowest placing of 19th, is astonishing, and his eight finishes on the podium remains a record.

His Paris-Roubaix record is also one of the best, reflecting the fact that the greats of cycling once viewed this race as essential to their careers: he finished the race 13 times between 1960 and 1977, finishing 10 times between 13th and fifth. His cameo appearance angrily waving a flatted wheel in Jørgen Leth's film A Sunday in Hell shows him on a day when he punctured multiple times and was probably strong enough to fight for the podium.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

His career remains one of the longest in professional cycling, beginning in 1956 and ending with a cyclo-cross race in 1977 when he was 41; a year earlier he had finished third in the Tour de France to Lucien Van Impe. He raced from the last days of Fausto Coppi and Louison Bobet, outlasted both Jacques Anquetil and Eddy Merckx, and hung up his wheels when Bernard Hinault was just beginning to make waves.

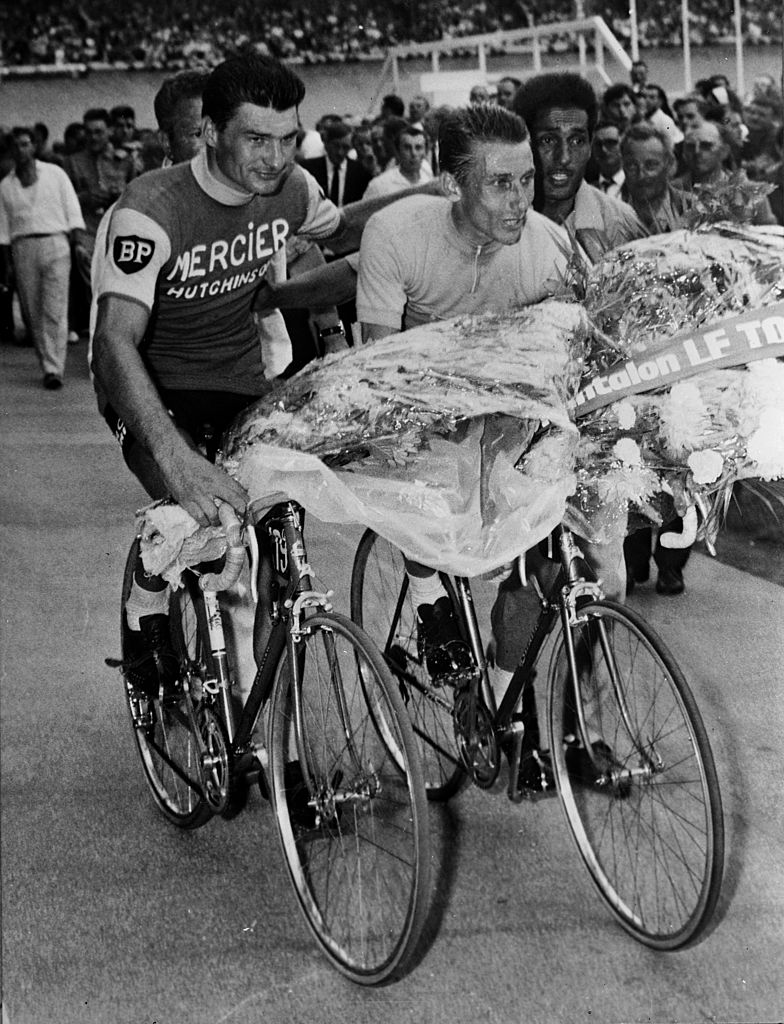

Within that time, his rivalry with Anquetil lasted only half a dozen years, and – at the Tour de France at least – always saw Maître Jacques triumph, but it defined the race for a generation of French fans, including the current race director Christian Prudhomme.

The photograph of Anquetil and Poulidor with their elbows locked on the climb of the Puy de Dôme is one of the iconic images of the sport, on a par with Coppi and Bartali swapping that bidon or Hinault and LeMond crossing the line at Alpe d'Huez arm in arm.

The Poulidor-Anquetil rivalry was real, albeit stoked by their respective agents, Roger Piel for Poulidor and Daniel 'Rockefeller' Dousset for Anquetil.

Each carefully nurtured their images: Anquetil the sophisticated man about town with a touch of the dilettante about him, Poulidor the homespun peasant with the accent of his native Limousin, who tried his hardest yet would be thwarted by malign fate and the clever guy from up country.

Both actually shared roots in rural France, but as the son of a strawberry farmer, Anquetil came from slightly higher up the social ladder, while Poulidor's parents were métayers – crop-sharing peasants who had to pay a percentage of their output to a landlord in rental. And for all his stolid looks, Poulidor had the cunning of a peasant who wanted to earn his way in the world; his criterium fees were bigger than those of the far more successful Anquetil, and – my favourite story, this – he would set up a poker school at pre-season training camps and win enough money off his teammates to pay his hotel bill at the end of the week.

Could Poulidor have won the Tour with a little more luck?

Possibly, but he was tactically inept on occasion, according to teammates and rivals. He variously mistimed stage finishes, chose to take the money for a criterium rather than checking out that key finish in the 1964 Tour at the Pûy de Dôme – where he used the wrong gear rather than 'fess up to his manager Antonin Magne, and collided with a motorbike in the 1968 Tour, which was his best chance of a win with Anquetil out of the picture.

As it worked out, his massive, enduring popularity and comfortable lifestyle showed that a cyclist could achieve 'greatness without the yellow jersey', to quote the title of his first, best-selling autobiography.

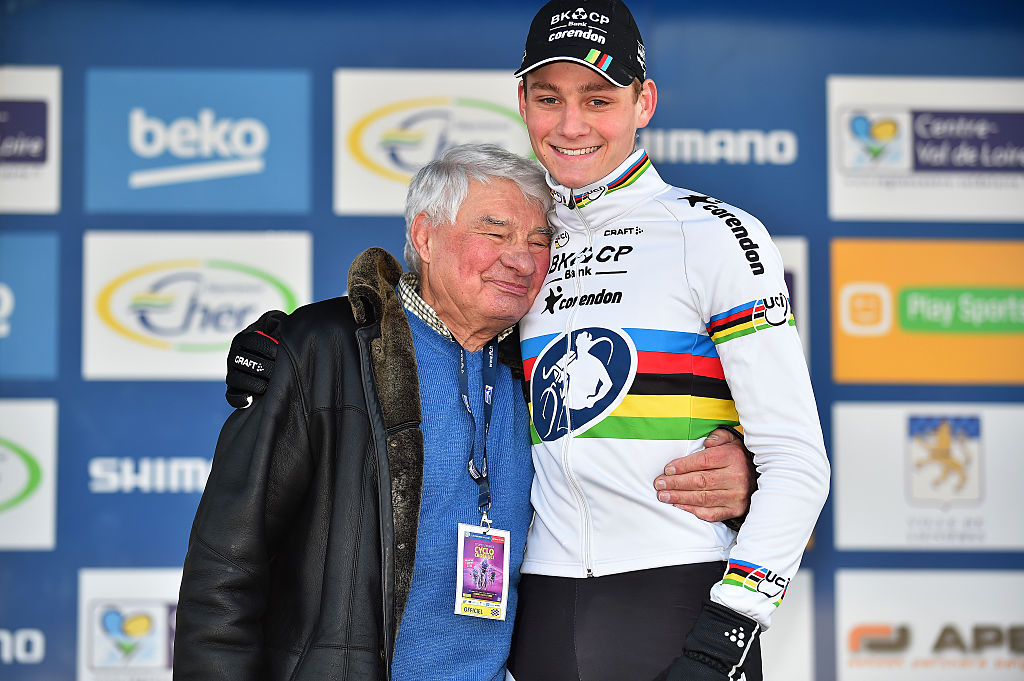

Poulidor leaves more than his Poupoularité and a name that in France is synonymous for continually missing out on the big prize. His two grandsons, David and Mathieu van der Poel, both race as professionals, with Mathieu having every chance of achieving a palmarès that could be the equal of his illustrious ancestor.

For a brief while in late September in Harrogate, Mathieu looked likely to take the road-racing rainbow jersey that eluded his grandfather; his valiant dramatic failure won him as many hearts as his wins, and was right out of the copybook in which Poupou inscribed so many courageous near misses.