RED-S and cycling: Red flags, role models, and recovery

The dangers to your body of this infrequently discussed condition, and the dangers to performance too

I’ve tried to be as open as possible about my relationship with food and cycling when the opportunity presents itself. My relationship with my own body weight has been pretty problematic in the past, exacerbated greatly by just believing I was ‘just being a cyclist’. I am happy to say that things are much improved, though I do feel it’s one of those things that is managed rather than ‘cured’.

I no longer note the caloric expenditure of my riding, and I’m certainly making a more concerted effort to eat better before, during, and after riding. I was however, until recently, unaware of the syndrome/condition/situation knows as RED-S, or relative energy deficiency in sport. The short version is that it is an ongoing imbalance between calorific expenditure and intake; either too much of one, or too little of the other. As you can imagine in a sport like cycling, where regular high calorie output days are often the norm you can see how it might be easy to unexpectedly slip into conditions like this.

What follows is a conversation I had recently with Pippa Woolven, founder of Project RED-S, a collaborative initiative that brings together athletes, coaches, supporters, healthcare professionals, and other sport stakeholders in a shared mission to increase awareness, prevention and recovery. She is a former elite athlete, a distance runner both before and after her experiences with RED-S. We sat down for an open chat about our own experiences; hers with the knowledge of the condition, and mine from a standpoint of only a passing awareness. For those that may find discussions of disordered eating difficult, consider this a trigger warning.

For context, the main image for this article was a picture I snapped while visiting a Would Tour team camp. Riders would routinely weigh their meals, but under the guidance of team doctors and nutritionists. That's not to say it isn't problematic, and has negative outcomes as we'll get into, but emulating these behaviours without the benefit of expert advice is where things get really dangerous.

Will Jones

I guess the best place to start is ‘What is RED-S?’

Pippa Woolven

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In its most simple sense, Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport is essentially a mismatch between energy consumed and energy expended, and when there is this mismatch it can affect every single bodily system, and your body will always prioritise movement over non-essential bodily functions. By non-essential, I mean things like the reproductive system, the immune system, male and female hormones... anything that isn't fighting to keep you alive. This has many knock-on consequences to all sorts of bodily systems, understandably, and it can occur by two main ways.

So even though you arrived at [RED-S] unintentionally through an illness, you then consciously decided to continue restricting your calories in order to meet the standards of sports culture and the dangerous toxic culture in cycling. Or you can enter into it simply by underestimating the energy requirements of your activity. A lot of people are just misinformed about how much fuel they need for their next exercise. They might know what they need to eat, but they just can't get enough. If you're cycling 100 miles a day, it's very difficult to compensate for that with your energy intake unless you're consciously really on top of it. Does that make sense?

WJ

Absolutely. I think a lot more people will be familiar with things like anorexia, where it's a deliberate restriction of calorific intake, and [RED-S] just sounds a kind of passive accidental thing that people don't realise is going on? Are there any key differences between the two?

PW

Regardless of the entry into the energy deficit, physically, the outcome is the same. Psychologically I think things are worlds apart. So as you know the harmful consequences mentally of intentionally restricting your food intake, over-exercising, or having an exercise addiction kind of takes over your life. It makes things very difficult socially, it can cause you to become withdrawn and distracted, and have difficulty concentrating. Whereas if you're simply just not quite getting the balance right, it might not impact every aspect of your daily life psychologically so badly.

Actually though, often there is just this interim where I think the term would be ‘disordered eating’ rather than eating disorder, because, yes, people can suffer from this with full-blown anorexia or bulimia, or exercise bulimia, there are also lots of disordered habits that could be classed as ‘disordered eating’ that might not meet the full clinical criteria for something like anorexia.

WJ

I'm feeling like it's potentially a lot harder to spot; harder to realise that it's something that is occurring? Or even if it is occurring, it's because of the setting in terms of it being part of sport. if you're in an environment where low body weight is idealised, more so than general society where it's idealised anyway, it's a lot easier to justify your disordered eating as trying to gain a performance advantage.

PW

Exactly, yeah. And so many disordered eating and exercise behaviours are normalised within sport settings, which makes it harder to identify when you've crossed that line between striving for excellence or performance, health, whatever, and being overly disciplined, disordered. Whatever you want to call it.

I actually think cycling, and male cycling, is one of the worst sports for this culture. Because, yes, there is a power-to-weight ratio and yes, to some extent your weight does matter, but the measures cyclists will take to achieve that are so shocking and so, so normalised. People talk about fasted rides as if that's a healthy thing to do.

People talk about fasted rides as if that's a healthy thing to do.

WJ

I was just thinking back to when I was much more regularly riding for ‘chasing performance’. I regularly go out before breakfast or go to work without breakfast. I get home and I'd be hungry, and I think well, that's great. That's a good thing. That's what I'm meant to be doing. And then I'd still eat. I'd still eat dinner, but I go to bed hungry. I think, well, I've had my dinner. I've had my three meals a day, I can't possibly be having a problem with food. I'm just hungry because I'm a cyclist.

PW

Exactly, [it’s] almost encouraged. And this is across all levels of cycling; I'm sure the elite athletes probably talk to nutritionists, but even they have seriously disordered eating behaviours that trickle down the recreational riders.

WJ

This is, I think, the big problem. I remember seeing an interview, I think with Geraint Thomas, and he was talking about how he used to go to bed hungry. And that's when I was like “okay, if he can do it, I can do it”. Maybe it's just a memory that I made up, but it's what I used to justify things to myself.

PW

It is so easy to do that; there is always this justification of the behaviours, which encourages them to continue. But, ultimately, it shouldn't be that way, and I wish that they were setting a better example.

WJ

What are the signs and symptoms, and how to spot it? From my point of view, as a bit of context, it took me completely stopping riding for two years because of a slipped disc to reset my relationship with cycling. When I came back to cycling, I couldn't initially ride the pace, or I couldn't ride for hours and hours, and so I was riding just for the fun of it, and not thinking about what I was eating, which was quite a change. What should we be looking out for?

PW

That kind of relationship with food and exercise can be both a precursor to and a symptom of this condition. So when you are in a state of low energy availability, you can start to become preoccupied with food and training, and that becomes the focus of your day. You might enter into this state completely unintentionally, but all of a sudden it sort of becomes an obsession.

The physical symptoms to be looking out for are low energy, low moods, any indication that the essential (or I guess you'd call them non-essential) bodily systems aren't functioning properly, because all of your energy is being directed towards the activity. For women, the main big red flag would be a missing menstrual cycle or an irregular menstrual cycle. For a man that might look like low libido, loss of morning erections, which is not something guys like talking about, but probably a lot of them experience. A poor response to training, poor response to overcoming an injury, and [more frequent] illness and injury is a big warning sign because you're not recovering properly.

For women, the main big red flag would be a missing menstrual cycle or an irregular menstrual cycle. For a man that might look like low libido, loss of morning erections, which is not something guys like talking about

WJ

From from my point of view I always seem to find myself with a bad knee, or a bad hip, or a bad ankle, or just little kind of niggles fairly regularly, but they're always easily attributable to something else. It was never ‘am I eating enough?’. It's ‘am I doing too much?’

PW

And to some extent, in sport, you expect to feel tired, you expect to get injured, and to get ill. But it's when these things become too frequent or too persistent. And you might also get the sense that something isn't quite right, and it becomes harder and harder to explain it away.

WJ

I guess that must be a fairly common pitfall? I'm thinking from the male perspective; obviously, as you said, from a female perspective you've got a missed menstrual cycle - that's a fairly obvious sign. I was wondering if this is potentially why it may be underreported in men, because a lot of them don't realise it's happening because there isn't such an obvious sign, or a reluctance to discuss erections.

PW

There's that stigma, and then there's the stigma that this condition is often associated with eating disorders, which guys will typically find it harder to fess up to or to admit that they're struggling, because, you know, they're guys; they shouldn't suffer from things like that.

WJ

Because eating disorders generally are feminised in the media?

PW

Totally. But then women face the added barrier of using something like the contraceptive pill, which will mask the missing period thing. So I think both guys and girls will have barriers, which is what makes us so difficult to identify on top of the fact that nobody wants to stop training, or eat more, and nobody wants to admit to a potential psychological problem.

I think we're starting to talk about this more as a metabolic injury. So just as you would get a knee pain, this is a systemic metabolic problem where all of your energy systems aren't working, right? And I think that kind of terminology makes it easier.

WJ

We're all fairly attuned to saying: I've got a knee injury. It's a lot smaller of a leap from knee injuries to metabolic injury than from knee injury to eating disorder or disordered eating or something like something of that nature.

So you wouldn't necessarily say it's more common in female athletes? It's just, you know, systemic throughout, but just underreported generally?

PW

I think so, yeah. I think we're really struggling to quantify the issue in both males and females. Females face added challenges in that being fasted for too long alerts the female hormone system that you're not in a position to procreate. And because you're the child bearer, it has worse consequences. It's more complicated in women, but I think just as many men suffer from it.

WJ

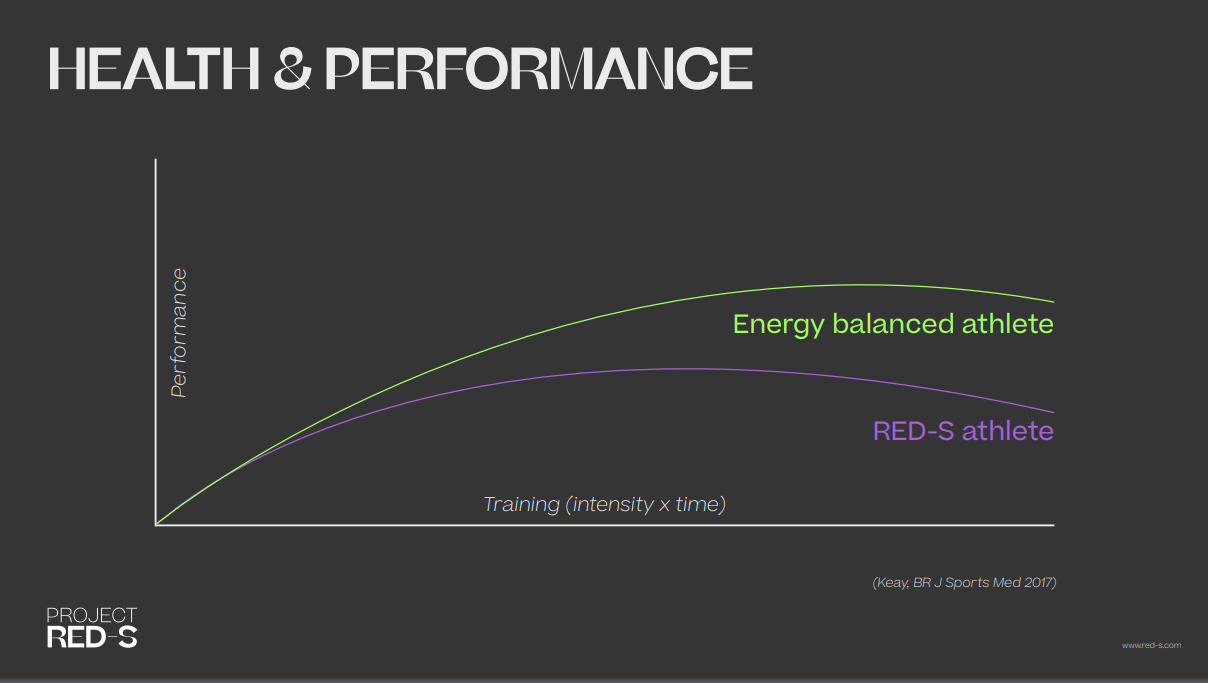

We're all chasing performance, and as much as anything else this can be a huge hindrance to performance, from what I can gather? If you're trying to get lighter to improve your power-to-weight ratio it feels like [you’re] doing the right thing, even though you're not necessarily doing the right thing. I guess, if the health impacts aren't enough to highlight this to people, then maybe the fact that it can actually be holding you back will be.

As a case study, I would always be chasing sort of the set average speed, and I kind of got to a plateau and it couldn't seem to get any faster, no matter how much I restricted my intake, or increased my volume of training load; I just couldn't get past it. Now I've started deliberately eating more I could quite easily go beyond that plateau having done far less training - incredibly frustrating to start with, but it’s a good illustration.

PW

I think you're absolutely right, in that a lot of us athletes are more concerned about performance than we are about our health; and that is just sports culture in a nutshell. It's like this win-at-all-costs mentality, you don't stop to consider the long-term consequences of what you're doing necessarily, you just want to be better in the moment. But ultimately health and performance will go hand in hand, and unfortunately, often with something like this, as you will have experienced when you start out on this process.

You're super light, your body hasn't yet caught up with the consequences of being in this deficit, and you can experience an initial performance boost. You haven't had the knock-on consequences on your hormones, or bone health or injury status, so you're riding this high for a while, and then it becomes ingrained in you that in order to perform that way, you have to do this, you have to eat this, you have to train this way. And when you've got all the media perpetuating that idea, it can become very difficult all of a sudden, when you reach this plateau, or decline, to believe that that's not the right thing to do.

So then you're in denial, you resist the advice that you're being given by a medical professional, or somebody who knows what this problem is. Ultimately, the only way around it is to eat properly, is to rest properly, is to change your training significantly, often. And unless you experience some kind of reward from doing that, it's so easy to give up on this new way of life, until you start to see the effects.

...a lot of us athletes are more concerned about performance than we are about our health; and that is just sports culture in a nutshell. It's like this win at all costs mentality, you don't stop to consider the long term consequences of what you're doing necessarily, you just want to be better in the moment.

WJ

We need an incentive to do it, a lot of us, which is not an ideal situation. Like you said, when I started racing cyclocross, that's when I really started sort of upping my volume. And initially, it was great, and I got better and better, and then I just didn't get any better. What's going on? Why isn't it wasn't continuing to work? I must just not be doing enough. Yeah; train harder!

PW

That is one of the most common pitfalls is thinking it must be lack of fitness; it must be something I'm doing wrong. I need to work harder. It's very frustrating. For an athlete or someone who's used to you putting a lot into something, it's really hard to be told to ease off.

What we lack is these positive role models, or people who have been there and successfully overcome this condition to reach the highest level of sport again, and even if you're an amateur, you want to look up to people who are doing this professionally.

WJ

Are there any treatments to this beyond “just eat more” or “just exercise less”?

PW

This isn't a very positive message, but just as you've described, for me, I had to reach this rock bottom, so fatigued I couldn't function, state of health before being willing to accept that what I was doing was no longer working. And that is the most common scenario that I see.

It's often the same with eating disorders and other mental health issues, which is so sad. But I think role models, this education, this awareness of what the condition is, will help with that. If you see a way out, a positive alternative to what you're doing - you might be more likely to test it. I didn't really have that. I had no one to show me: Look, you can overcome this and reach a decent level of health and performance in future.

But ultimately, it's eat more, do less, and there's no dodging it. It's a journey of learning how your body works when it's telling you that something's not quite right, and how to respond to that. And, I mean, it took me years to get that nailed down.

WJ

Do you think a cultural shift is far more effective than an individual diagnosis?

PW

Totally. There's definitely a place for a diagnosis because for me, I was sort of suffering on and on with this not knowing what it was, and once I was able to identify with a condition as like: Ah, okay, RED-S, that's exactly what this is - I've got a name for it, which means I can do something about it. So that is important, as is a dietician to say “look, you should be eating this many carbohydrates, this much protein”, but the whole point of Project RED-S is to bring together this community of athletes, coaches, healthcare professionals, everybody, every sport stakeholder, to try harder to market this as a problem that needs solving.

WJ

Seems like a good point to tell us more about Project RED-S.

PW

Yes. So the answer, the easy question is to find it, you go to red-s.com. The basic premise behind it is to form this collaborative initiative, which brings together athletes, coaches, parents, supporters, partners, healthcare professionals, officials, governing bodies, to be talking about this, raising awareness, sharing experiences in order to improve prevention, and increasing recovery outcomes by directing athletes to the right medical specialists, to the right dieticians who aren't telling them to cut out dairy or carbohydrates or gluten or whatever, but [ones that] understand this problem. More importantly, we're just trying to talk about this; we're trying to break down barriers, stereotypes, and we're trying to be as inclusive as we can, because we know how many people this affects.

It’s worth noting that, while raising awareness is incredibly beneficial, it’s also possible for change to come from the top down too. Norwegian riders, under the jurisdiction of the Norwegian olympic committee, can be denied racing if they are showing symptoms of conditions such as RED-S, such as missed periods. This commitment to rider safety is admirable, and hopefully something that will be taken on by other governing bodies.

Given the subject matter it's prudent to also provide you with some links for where to go, beyond the Project RED-S website, if you are struggling with, or need further information on eating disorders of any kind

U.K.

Beat - The UK's eating disorder charity is the place to go for information and support, or you can find the individual phone numbers and email helplines for England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland on a separate page.

U.S.A.

NEDA - The National Eating Disorders Association is your best bet for a first port of call if you need information. Contact details are available too, for an online chat, a phoneline, or a text chat if you need more immediate support.

Will joined the Cyclingnews team as a reviews writer in 2022, having previously written for Cyclist, BikeRadar and Advntr. He’s tried his hand at most cycling disciplines, from the standard mix of road, gravel, and mountain bike, to the more unusual like bike polo and tracklocross. He’s made his own bike frames, covered tech news from the biggest races on the planet, and published countless premium galleries thanks to his excellent photographic eye. Also, given he doesn’t ever ride indoors he’s become a real expert on foul-weather riding gear. His collection of bikes is a real smorgasbord, with everything from vintage-style steel tourers through to superlight flat bar hill climb machines.