Racing below the breadline: The women’s cycling omertà

The tragedy of Rebecca Twigg’s homelessness and the problem of poverty in the women’s peloton

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Around this time two years ago, an article in VeloNews dropped a distressing piece of information at the end of a paragraph, like a stone into a pond. When the Seattle Times amplified the story with an interview a few weeks later, the shock ripples spread throughout the cycling world.

The news in question was that Rebecca Twigg, one of the great champions of women’s road racing from the 1980s and early 1990s, was homeless.

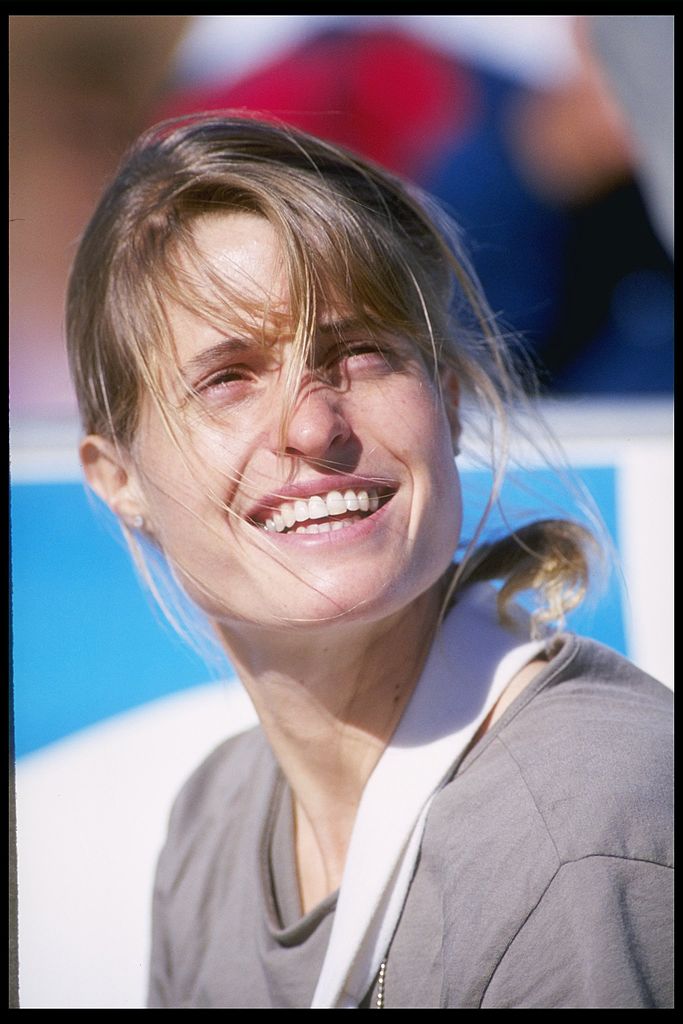

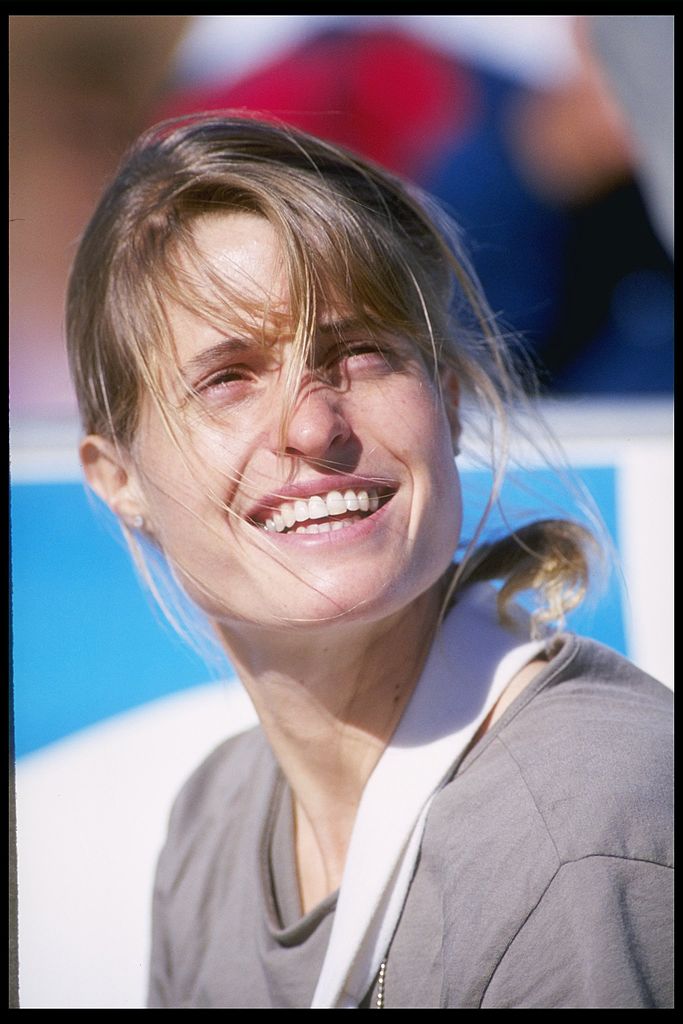

Rebecca Twigg’s story seems like an American fairy tale that went horribly wrong. She was a child prodigy who went to university when she was only 14 and began racing shortly after, winning medals right from the start. She famously came second in a photo finish to her older teammate and rival, Connie Carpenter-Phinney, at the first-ever women’s Olympic Games road race in Los Angeles in 1984. Equally gifted on the track, she won no fewer than six World Championship gold medals in the 3,000m individual pursuit. She broke world records. She won the Coors Classic and three consecutive editions of the Ore Ida Women’s Challenge—stage races that were an American version of the Tour de France.

“She always impressed me with her supple pedalling style—perfectly round, fluid, even silky, her head and shoulders steady,” recalls Peter Nye, the author of Hearts of Lions: The History of American Bicycle Racing. “The word poise comes to mind. Whatever speed she was going she made it look easy.”

He recalls one particular circuit race in which Twigg sat at the back of the peloton, “cruising like she was passing time”. As the race reached the final laps, “she disappeared from the rear, threading the needle through the pack. At the bell lap, she held a good position and the peloton was strung out. Within sight of the finish line, she spun away from all the supporting players like she owned the race.”

She was strikingly attractive, her radiant good looks appearing in adverts and on magazine covers, immortalised most memorably in an Annie Leibovitz shoot for Vanity Fair. She was kind to other riders and to her fans, especially young girls who dreamt of turning pro. If the message boards of cycling forums are anything to go by, she was the crush of just about every straight American male cycling fan of the time.

It would be hard to imagine a more perfect ambassador for the sport, and it’s difficult to comprehend now how the life of someone so talented, intelligent and captivating could go so badly awry.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

But Twigg’s life wasn’t quite so perfect as it appeared on the outside. She took a career break when she was 26 after burning out from overtraining. She had two marriages that ended in divorce. She had a few bad crashes and concussion. She walked out of the 1996 Olympics—and the following year her career—after clashing with her coaches over having to use a ‘superbike’ she didn’t get on with.

After she retired, she dropped off the radar. What had become of her was a mystery. A famously-private person, she seemed to have become a recluse.

Those who did know about her situation were burdened with having to respect her request for privacy, unable to call on the large network of friends and fans who could have activated a GoFundMe campaign or set up other helpful initiatives.

Twigg finally agreed to be interviewed by the Seattle Times in 2019, she said, because she wanted to correct the assumption that homeless people are all drug addicts, and to show that the struggle to get or hold down work, or indeed just make sense of life, can also happen to the kind of high achievers we like to assume are life’s winners.

Pitfalls of retirement

We know that even the most successful athletes can go off piste when they retire: Charly Gaul, one of the legendary climbers in the Tour and the Giro in the 1950s, spent a long period shunning human contact and living like a hermit after his racing career ended; Alexi Grewal, who on the same day Twigg took silver at the Olympics, won the men’s gold medal in the road race, is said to have endured a period of homelessness; Marco Pantani, who won the Grand Tour double in 1998 of the Giro and Tour, died tragically young of a drug overdose.

Any number of factors can exact a heavy mental toll on elite sports people as they transition to ‘civilian’ life. But female cyclists retire with an additional burden compared to their male counterparts, since the vast majority of women leave the sport with no savings, no pension scheme, and a lot of debt.

Even Twigg, who at the peak of her career never lacked for team contracts and advertising deals, never earned more than $50,000, she told the Seattle Times (in 1993, this would have been equivalent to about $90,000, or €74,000 in today’s money). It didn’t really leave anything to fall back on and was certainly nothing compared to what male riders of her standing would have earned.

Racing below the breadline

What’s even more shocking is that $50,000 even today (roughly €41,000 at today’s exchange rates), some 30 years later, would make a female rider one of the higher earners in today’s peloton. A survey conducted in 2017 by The Cyclists’ Alliance, which campaigns for female riders’ rights, revealed that only 8 per cent of the women’s peloton at the time was earning more than €40,000. Even worse, half the peloton was earning €10,000 or less and 17 per cent of pro riders earned nothing at all.

The last few years have seen tremendous changes in women’s racing, not least with the introduction of a women’s minimum wage and the introduction of paid maternity leave at UCI WorldTeam level, which came into effect last year. There was much discussion as the UCI’s plans were revealed as to whether the women’s sport could handle the new budget requirements, or whether teams would fold.

But despite the unprecedented disruptions to last season with the coronavirus pandemic and its resulting economic aftershocks, there are now nine women’s teams with a UCI WorldTeam licence, which means that all their riders at the very least will receive a wage of €20,000 this year. Next year, the minimum wage will rise to €27,500 and in 2023 women’s UCI WorldTeam licensed teams have to match the minimum wage of the men’s Professional Continental Teams.

Trek-Segafredo has upped the ante this year, ensuring that riders on their women’s team receive at the very least the same base salary as the men, which is €40,045. Some of today’s female superstars can even be described as wealthy: Annemiek van Vleuten has seen her salary rise from €125,000 riding for Mitchelton-Scott in 2020, to €250,000 with Movistar this year.

To make the comparison, however, a good domestique in one of the top men’s teams will earn between €100,000 and €400,000. Stars like Alejandro Valverde, Julian Alaphilippe and Vincenzo Nibali were all earning over €2 million last year, while Chris Froome and Peter Sagan take home more than double that.

The women’s minimum wage is a welcome change that’s been a very long time coming, but we still have a situation where another 48 Continental women’s teams get to call themselves professional with apparently no obligation to pay their riders anything at all: and there are still many that don’t.

Some even make their riders cover their own expenses. “You have teams that say, we’re going on training camps, everyone has to pay €300,” says Iris Slappendel, Executive Director of The Cyclists’ Alliance. Or riders “have to go to races and they have to take their car or they pay their own costs, they have to pay their own lunch. That still happens.”

The reality for most women in today’s peloton is that they are obliged to take on extra jobs in order to make ends meet.

“It’s really only a small handful of riders who—whether it’s thanks to sponsorship, salaries or a national team stipend—can bridge the gap,” says retired pro and campaigner Kathryn Bertine, whose book “Stand: A Memoir on Activism. A Manual for Progress. What really happens when we stand on the front lines of change,” published earlier this year, details her journey campaigning for parity in women’s and men’s cycling.

In 2016 Bertine set up The Homestretch Foundation, a charity that offers riders up to six month’s rent-free accommodation at a communal house in Arizona, where they can train in optimal conditions. While the project is laudable, its very existence is a shocking indictment of the state of women’s racing today.

It needs to be reiterated that professional riders on UCI-accredited teams are expected to devote at least 20 hours a week to training, their weekends to racing and be present and correct at all the key events on the calendar. They are ‘professional’ in every sense of the word, other than the one that gives it its meaning.

What is it like, in day-to-day terms, to be an under-paid professional cyclist?

Doris Schweizer is a four-time Swiss national champion who, like so many pro riders, does an additional part-time job to pay the bills. Given the training hours and the irregularities of the racing season, the sorts of jobs riders can do on the side tend to be “student jobs”, she explains.

Before the pandemic arrived last year, Schweizer was working for McDonald’s, which has its advantages and disadvantages. “They are really kind because they like sports,” she explains, “so they make it possible for me to take time off, even two months. And I’m also flexible in saying that I want to work in the evening, or in the morning.” On the other hand, the job meant she was constantly on her feet.

“Sometimes it’s really exhausting because the day has only 24 hours, and if I’m away for two months I have to work more when I’m here. So, when I’m not racing, I basically train and work and sleep: that’s it. You can manage it physically, but you get really tired mentally: you cannot recover. You wake up and it’s like; breakfast, training, and then you eat and go [to work], then come back and sleep. And I think this is maybe the most challenging part.”

Schweizer isn’t totally negative about having to take on extra work. Indeed some riders argue it instils a resourceful mind-set, which stands them in greater stead when they retire than male pros that have spent their careers in a bubble devoted only to racing.

But there is no ‘off season’ for an underpaid female rider, who can never take any time off, let alone go on holiday. “I think it affects you,” says Schweizer; “sometimes you have to take a day off from training because you’re too tired.”

The last 12 months with the ‘on/off’ pattern to lockdowns have dramatically disrupted these norms, of course. Schweizer still works for McDonald’s but like many in the restaurant industry, she has endured frightening periods of no work at all, followed by intense 50-hour work weeks. Currently contracted to a US team, she is unable to race for the moment because of travel restrictions but has appreciated more than ever the distraction and sense of well-being she gets from being able to train. She had planned to start a part-time university degree in September but that has now been put on hold.

“The pandemic has taken away all my life plans,” she says. “In the big picture we all just lost a little part of our careers - but it also gave us a chance to think about what we really want in life and what matters to us.”

Why ‘just enough’ is not enough

At the peak of her career, TCA's Slappendel says she earned €24,000 a year riding for Rabobank and Cervélo, which she says was, in cycling terms, a very good salary. But trying to live off that sort of money came with many sacrifices.

“For maybe eight years I never went on vacation,” she says. “You don’t go out for dinner, you don’t treat yourself with luxury stuff or go shopping... You’re just very, very careful with how you spend your money.”

Slappendel knows many riders in today’s peloton that are having to live off unemployment benefit and points out that if you’re earning less than €10,000 a year, “there’s no way you can rent a house and just take care of yourself,” adding that many riders, “make the choice to live with their parents for longer, or off the support of their husbands or boyfriends.”

“That’s a solution, not the answer,” says Bertine, who at one point following a divorce, moved back in with her father and took on two additional jobs to support her racing career.

Many teams will put riders up in team houses during the racing season, but if a rider doesn’t have a salary, Slappendel points out, they still, “have to use their savings to buy groceries. They don’t have transport, they don’t have a car, they have to go everywhere by bike.”

“Some friends have to count their money so they can buy enough food until the end of the month,” Schweizer says.

Mental well-being is a constant issue. For a rider on a salary that is ‘just enough’, “it’s stressful every day”, Schweizer explains, because “if something happens, then you have nothing.”

Those ‘somethings’ can include a team not honouring its contracts and paying its riders, a depressingly common occurrence. In her memorable retirement speech Nicole Cooke talked of going to court four times in her 11-year career in order to get her wages paid – including in 2012, when she was reigning Olympic Champion. Imagine for a moment being a young woman from Australia or South America, say, living in Europe during your first professional racing season and suddenly your salary stops coming through. “What do you do?” asks Slappendel.

Other teams expect riders to pay for their own health insurance, which can result in riders having inadequate coverage when they race in other countries. “Sometimes for me it was: ‘I hope I don’t crash,’” says Schweizer, “and if you think like this, it’s difficult, because racing means crashing.”

Inequality and the two-speed peloton

Inevitably, if half the riders in the peloton can’t train and recover in optimal conditions, then no matter how talented they are, they will be at a significant disadvantage to those who can. Though it’s provocative to say so, and it’s hardly the fault of the riders, it’s tempting to draw a comparison with performance-enhancing drugs that allow an athlete to recover faster and train harder. It is abundantly clear that those who have the financial resources to concentrate on their racing full time have an enormous advantage over those haven’t.

“You can’t put your best effort in to your athletic career when you have so many hurdles in front of you,” Bertine explains. “The proof is on the podium. Homestretch women are doing well because we have relieved them from the burden of paying their rent.”

Similarly, those who can live rent free thanks to their families or partners have a significant advantage over those who can’t, which creates conditions for a lack of diversity in the peloton.

It’s not dissimilar to the internship system, where young hopefuls are expected to accumulate unpaid work experience before they can hope to get a proper job, or the freelancers’ bugbear of ‘exposure’ in this age of online everything, where creatives are expected to produce content for free, which will then bring them a ‘shop window’ that, supposedly, will bring in paying work. If you can’t afford to do those things, then you most likely won’t get ahead in those worlds, no matter how talented you are.

“It is an expensive sport,” Slappendel points out. “Already when you start out you need a bike, you need wheels, you need equipment, then you crash, and you start all over again. I’ve always been cycling without support from my parents but especially to reach a certain level, if you’re not picked up by a team [that pays its riders], then it’s pretty hard.”

Making the choice

Of course, no one is obliged to become a racing cyclist. It’s a choice riders make, in the full knowledge that it won’t make them rich. And it’s only in the last 30 years or so that women’s racing has been professionalised at all.

For most riders, their love of the sport outweighs the financial hardships they take on. “If it were more stressful than the enjoyment I get from it then I would stop,” says Schweizer.

And who hasn’t fantasised about waving goodbye to the desk job and embracing a simple, monastic life of devotion to the bike? Many people would pay good money for such an experience.

“You don’t have a lot of expenses,” Slappendel points out. “It’s quite a cheap life as well: you don’t have to go to parties every weekend, you don’t have to buy beer, you don’t have to buy new clothes, you just wear your kit all the time.... It could be a pretty cheap lifestyle.”

You’d be living the “counter-culture, vagabond cycling life” as Connie-Carpenter Phinney described her racing years in her memorable contribution to Ride the Revolution: The Inside Stories from Women in Cycling.

“Until a few years ago I would always say, the great thing about women’s cycling is that that nobody’s in it for the money, we all do it out of passion,” says Slappendel. “Yeah, of course that’s great, and it’s true, but there is a certain point that we should also start thinking, how far can passion take you?”

“In any profession it’s normal that you struggle at the out start,” says Bertine. “You ‘pay your dues’. If you go to medical school you take on debt, but there’s a job at the end of the tunnel.”

In women’s professional cycling, however, upward mobility is the exception for a lucky few, not the norm.

The women’s omertà

The inevitable question many might ask here is why aren’t women shouting from the rooftops about this? Why isn’t this considered a scandal? Talking about poverty in cycling seems to be as big a taboo as discussing doping.

“No one really wants to talk about it. But I think a lot of riders are struggling”, says Schweizer.

“I don’t know but I think it’s… maybe it’s you don’t want to be weak, in a way,” she offers. “You’ll probably speak to your friends at home about it but not to your teammates.”

“I think they feel ashamed about it,” says Slappendel. “Because on the outside they want to be, ‘Hey, I’m a pro cyclist, I race for this XYZ UCI team’.”

And then, of course, nobody wants to lose their job. “Every year I have riders calling me with complaints: they have no salary, they don’t get their prize money, they have to pay for their own expenses. Very often a team manager tries to rip them off,” Slappendel says.

“And I say, OK, shall we go to the UCI or their federation to file a complaint? They say, ‘no, I don’t want to file a complaint because then I won’t get a spot on the team next year’. I mean for me, then I’m also a bit like, you know, what do you want?”

Slappendel cites, as an example, winning a lawsuit on behalf of a Canadian on an Italian team who didn’t get paid for four months. “And I know they didn’t pay any other rider,” says Slappendel, although this particular rider, “was the only one who wanted to make a case out of it.” As a consequence of her action, “the team also tried to sue her for loss of sponsorship.”

When teams behave unscrupulously and riders are cowed into not talking about it, this starts to resemble an abusive relationship.

At the same time, the current generation of riders is social media savvy, and instinctively understands that no one wants to hear ‘moan-y stories’. Female riders feel a sense of responsibility with regards to promoting their sport and making it exciting for fans (something that is not always evident amongst their male counterparts). So their Instagram feeds are upbeat and entertaining and full of inspiring imagery. Complaining about being badly treated is strictly off-message.

Sponsorship: The eternal debate

Cycling is a commercial sport, and the economy of women’s racing is infinitely smaller than that of the men’s. It’s all very well to talk about a minimum wage, one might argue, but who’s going to pay for it?

Schweizer believes many teams would willingly pay their riders better, if they had the means. “They would like to pay more but they just can’t. Also, a lot of staff aren’t paid well, it’s not only the riders, it’s the whole team.”

Unpacking the reasons as to why there’s less money in women’s racing could fill a book, filled with contributions from riders from the noughties, a decade which began with a vibrant scene and ended with a mass extinction of races and sponsorship.

But even if we just focus on the here and now, it really doesn’t take a degree in marketing to understand that if you televise women’s races, you will engage an audience and attract sponsors, and if you don’t, you won’t.

For years naysayers have argued that ‘no-one’s interested in watching women race’. That argument is becoming increasingly tenuous, especially on the occasions when men’s and women’s versions of the same event are being televised. The statistics we are now getting show that women’s viewer figures are shooting up year on year, in direct correlation with the amount of exposure they’re getting. There are even occasions when women’s viewing figures eclipse the mens’, as the Dutch sports economics researcher Daam van Reeth often points out, most recently following this year’s Amstel Gold Race.

A recent edition of Rouleur Magazine – the first time the magazine has ever devoted entirely to women’s racing – was the fastest-selling issue in its 14-year history, selling out twice and going into three print runs. Perhaps just as significantly, all the adverts within its pages starred women in their action shots.

Women’s racing is hot, and it’s growing.

So why isn’t there the money to pay female professionals enough to live off? Slappendel and Bertine argue that it’s out there, but that cycling culture is stuck in the past.

“There are still so many old-school people in cycling,” says Slappendel. “And they just think that you go to the local flooring shop or whatever and you ask for a bag of money and then you’re done for the year, and you hope they pay it.”

“One of cycling’s major downfalls,” Bertine points out, “is that it’s the managers, who have come up through the ranks of cycling, usually as an ex pro, who are also the people trying to run the business and drum up sponsorship.

“The teams need to hire marketing directors whose role is to look for sponsorship and investors, who should be hustling all the time,” she says.

“There are many teams with a roster of 10 pro women. To receive a proper base salary of $40,000 for 10 riders that’s $400,000. That’s a fraction of what some men earn in this world. The money is there.”

What happened to Rebecca Twigg?

We like to think that being a great athlete is an excellent experience to bring into the ‘civilian’ workforce. In America, it’s the lacrosse team ‘jocks’ at college who traditionally get the plum jobs at Wall Street. In France, you can’t get into certain elite universities that act as incubators for the country’s ruling class without passing a sports test.

But in truth, it’s not so easy for a professional athlete to transition to the daily grind of office life. You may be a model of self-discipline with a breath-taking work ethic, but if you’ve spent most of your adulthood focussed on your personal sporting goals, surrounded by coaches and team directors making decisions on your behalf, it may be very hard indeed to make the transition to a more quotidian existence.

The first time Twigg quit cycling, she went back to university to study computer science, then worked as a programmer. She struggled to conform to office life after racing, however.

“Once you’ve done something that feels like you’re born to do it, it’s hard to find anything that’s that good of a fit,” she told the Seattle Times.

After the International Olympic Committee announced it was introducing her specialist discipline, the 3,000m individual pursuit, at the 1992 Olympic Games, Twigg returned to cycling and after only nine months of training she took bronze in Barcelona.

When she retired for good in 1997, she went back to working in IT. Inga Thompson, an equally impressive rider who was a contemporary of Twigg’s, described some of the factors that can affect elite athletes trying to reintegrate the workforce.

“As a racer, you’re used to having a schedule kind of rotate around you because you can’t overtrain, you don’t want to under-train, and you’re able to say, ‘I’m not doing that today, I’m doing this today.’ And Rebecca, being so highly trained, and highly attuned, had the leeway of making those calls.”

Thompson, who set up a cattle ranch when she retired, and describes herself as “unemployable”, said, “What Twigg had is a great trait, unless you get into the workforce.”

In her interview with the Seattle Times, Twigg revealed that she has always had a rootless existence. Her mother kicked her out of their home a few months before she turned 16. As she became a cycling star she moved between friends’ houses and hotels and the Olympic Training Centre in Colorado Springs.

For all its romance, living the beatnik dream rarely ends well for poets, and it’s not so good for riders, either. You cannot live forever in your 20s.

If you have spent your racing career leading a hand-to-mouth existence, unable to put savings aside, set up a pension scheme or put down a mortgage on a house, it can cast a long shadow over the years that follow.

For women there is the additional existential question of whether to pursue a new career or start a family. If you’re starting from zero in your early 30s, with a 10-year gap in your CV, the challenge of pulling off both things successfully is tough.

Twigg told the Seattle Times that after she went back into IT work she would suffer from anxiety attacks. She would take unscheduled time off. She walked out of one job because she thought she was about to be fired when she wasn’t. She would apply for jobs and then find herself unable to respond to invitations for interviews. After turning 50, it seemed the jobs being posted in her specialist domain were no longer open to her anyway, but to younger college graduates.

About seven years ago she started living out of her car and in women’s shelters, while her 14-year-old daughter from her second marriage went to live with relatives.

Talking to those familiar with Twigg’s circumstances, it would seem her situation is not, straightforwardly, one of losing work and failing to keep up mortgage payments. It seems there are mental issues, too.

She has, on several occasions, refused help from friends who have tried to find accommodation and work for her. She talked to the Seattle Times about having had “unfair advantages” in life, and said, “I felt at one time that I couldn’t accept housing because there were all these other people who need it.”

“The point is not so much that I need help, it’s that there are a bunch of people who need help – 12,000 in this area, half a million in the country. Help should be provided for everybody, not just a few.”

Her story is also part of a bigger crisis affecting many wealthy nations, of escalating rents and house prices, which even before the arrival of COVID-19 coronavirus had been leading to an explosion in homelessness among low-income families.

Since the start of the pandemic, Seattle’s shelters have been shut, and it is thought Rebecca Twigg is staying with family.

For the vast majority of female professional riders, there is no career advice, no financial buffer that allows them a bit of time to find a job, or to work out what to do next.

Yet, those who have always had to work on the side are probably more able to navigate their way through the post-racing life. The sad irony of Twigg’s case is that perhaps she was too successful in her racing career.

The worry is that any female rider who is not supremely resourceful, who is at all vulnerable to depression or anxiety, is, perhaps like Rebecca Twigg, at risk of slipping between the cracks in later life.

USA Cycling has not responded to requests for comment on Twigg’s story, or on whether there are any structures in place to help riders in their transition to retirement.