Preview: Giro d’Italia enters uncharted terrain on the gravel of Campo Felice

Evenepoel and Bernal lead the billing but summit finish can recast the GC

Uncharted territory. Remco Evenepoel (Deceuninck-QuickStep) had never raced for more than seven consecutive days before passing that landmark on the road to Guardia Sanframondi on Saturday. The Belgian now faces into more undiscovered country on stage 9 of the Giro d’Italia, when the race climbs to its highest point to date with the novel summit finish at Campo Felice, which features 1.6km of gravel road at the top.

The ski station above Rocca di Cambio is the second biggest in southern Italy after that nearby Giro staple, Roccaraso. Among its proudest boasts is that it was the preferred winter holiday destination of Pope John Paul II. Evenepoel, the man whose every move on this Giro is being relayed back to his native Belgium in the same detail as a papal visit, acknowledged on Saturday that the stage through the Apennines to Campo Felice would be the most demanding of the race to date.

“I think tomorrow will be more hard than today [stage 8], and I think guys like Egan [Bernal] and Ineos have a plan for tomorrow. A lot of GC guys will try to attack,” said Evenepoel. “I expect changes in the GC.”

After Evenepoel matched Bernal’s acceleration in the finale at San Giacomo on Thursday afternoon, it became tempting to begin couching this Giro as a straight duel between those two marquee names, given that they currently occupy second and third in the overall standings, 11 and 16 seconds behind maglia rosa Attila Valter (Groupama-FDJ).

Yet for all that Evenepoel and Bernal have impressed thus far – the Belgian in particular, given his long absence from racing – the top end of the general classification remains tightly packed. João Almeida (Deceuninck-QuickStep), Jai Hindley (Team DSM) and George Bennett (Jumbo-Visma) have conceded heavily, but there are still 11 riders within a minute of the pink jersey.

Simon Yates (Team BikeExchange), ninth at 47 seconds, bled seconds at Sestola and San Giacomo, but there is as yet no evidence that this constitutes anything more than a flesh wound to his overall prospects. Aleksandr Vlasov (Astana-Premier Tech), fourth at 24 seconds, and Hugh Carthy (EF Education-Nippo), fifth at 38 seconds, are well positioned. Giulio Ciccone of Trek-Segafredo in seventh at 41 seconds and Israel Start-Up Nation's Dan Martin in eighth at 47 seconds look like men on the rise. Valter himself has spoken of keeping the jersey.

Campo Felice will undoubtedly serve to confirm or rebuff some of the Giro’s early trends, and it might settle issues such as the leadership of Trek-Segafredo, where Vincenzo Nibali (16th at 1:43) already appears to be resigned to the current direction of travel. “We have Ciccone who is going strong, it's right to stay close to him and to support him as a team,” Nibali said on Saturday.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

This Giro, which has interspersed sodden, climbing stages with stressful days on the flat through its first week, has been attritional thus far. It would be no surprise if another lofty name slipped out of the race for pink on Sunday, where the road climbs for most of the final 40km, and where the last mile of racing takes place on gravel roads.

“It might be fun, but it might be a thrill for nothing. If you get a puncture there, it can have serious consequences,” Evenepoel said on Saturday. “Does that have to happen in a mountain stage? No, I don't think so. It could do a lot of harm to your Giro.”

The terrain

It’s not just about the final 1.6 kilometres of dirt road that rise to the finish at Campo Felice, of course, but everything that comes before it. With some 3,400 metres of climbing crammed into 158 kilometres, and with rain a distinct possibility, this is a stage with the potential to force gaps greater than the handfuls of seconds won and lost among the strongmen at Sestola and San Giacomo.

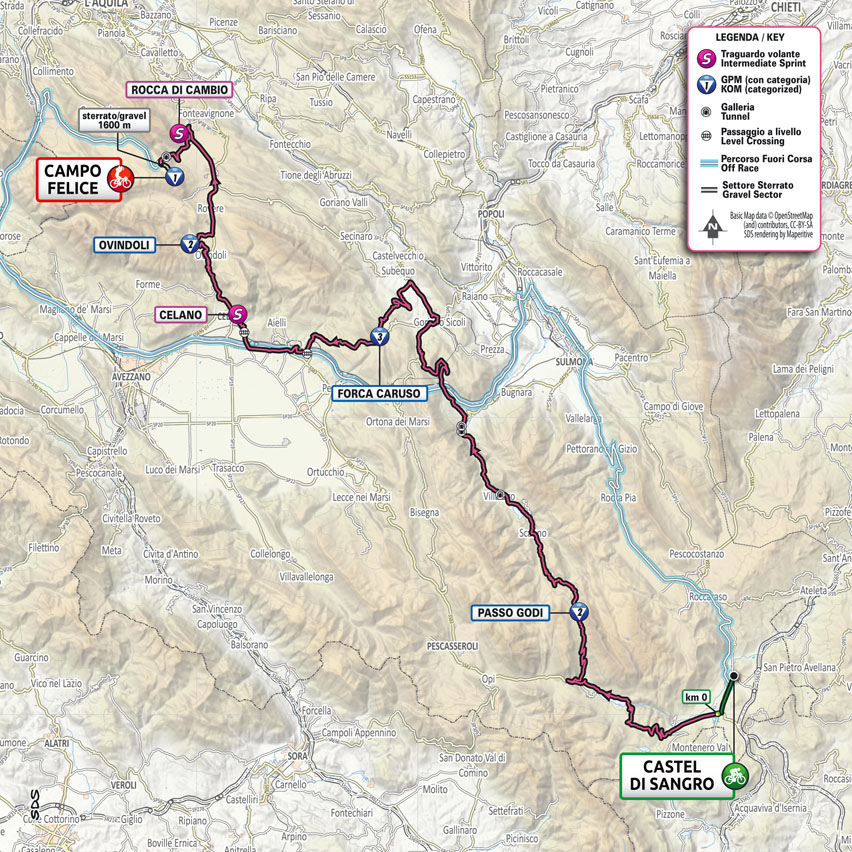

Stage 9 gets underway in Castel di Sangro, site of the late Joe McGinniss’ Miracle of Castel di Sangro, and the road climbs immediately from kilometre zero, with the gruppo taking in the gentle, unclassified Colle della Croce before tackling the category 2 Passo Godi (14km at 4.1 per cent).

Another uncategorised ascent, the Fonte Ciarlotto, follows. This terrain is fertile for the early break and unlike to cause immediate distress in the pink jersey group, but the cumulative effect will begin to tell by the time the stage enters its final hour after tackling the category 3 Forca Caruso (12.7km at 4.3 per cent).

The most obvious difficulty comes in the closing 40km or so. After the first intermediate sprint at Celano, the road begins its long, two-part ascent towards the finish at Campo Felice. First up is the category grind to Ovindoli, which climbs for 12.4km at an average of 5.1 per cent and with pitches of 10 per cent.

There is precious little in the way of respite from here on. At the summit, 1457 metres above sea level, the peloton treks along the plateau towards Rocca di Cambio, where Paolo Tiralongo won on the 2012 Giro. The town is the site of a bonus sprint, which serves as prologue to the stiff final climb to the finish.

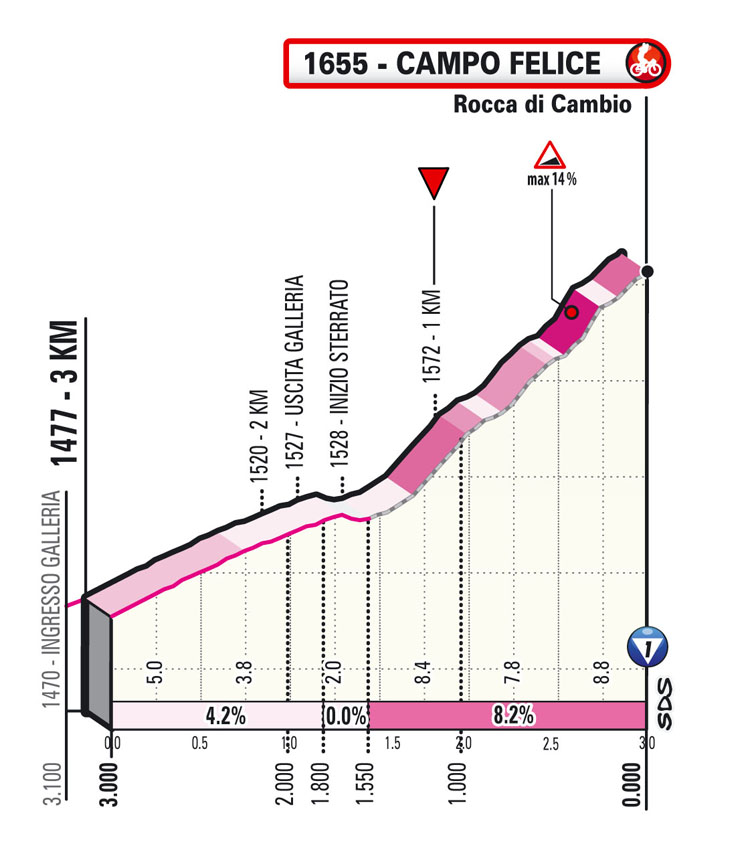

The ascent to Campo Felice is 6.6km long at an average of 5.8 per cent and, crucially, its toughest sections come right at the top. The concluding gravel section averages 8.6 per cent but includes ramps of 12 per cent as the Giro climbs to the highest point (1655 metres) on route from here to the Zoncolan next week. Milan won’t be visible from the top, but this is a taste of the hardships to come.

“I checked the rest of the stages in the Garibaldi today,” the pink jersey Valter said on Saturday evening. “The race hasn’t even started yet.”

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.