Pidcock's dad and Wiggins' son: The future of bike racing

We ride in the team car at Kuurne Juniors and see hard knocks, sticky bottles, young dreams and an old hand

Hanging around by the start of Kuurne-Brussel-Kuurne Juniors, after seeing the elite race off, I spot Giles Pidcock, boss of the Fensham Howes-MAS Design team and father of Tom. He’s busy getting the car ready ahead of the roll-out, but I introduce myself anyway.

“Oh hi,” he says. “Do you want to get in?”

“What?”

“Come and see the race if you like. You’ve got 30 seconds to decide.”

My day was shaping up like any other at the Classics: set up in the press room, work on a couple of stories, and tuck into the free sandwiches.

I get in the car.

“So, what do you want to know,” Giles asks.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

I tell him that I’d heard he was bringing a team over from the UK, and that one of his riders was a certain Ben Wiggins. A team with Brad’s son and Tom’s dad – sounds like a good story.

“Oh right,” he says, disappointment emphasised by the awkward silence.

“We’re trying to avoid the whole thing about him being Brad’s son. He’s already had loads of people coming up to him and it’s not really helpful. We want him to be Ben Wiggins, not Bradley’s son.”

Likewise, it’s not hard to sense that Giles is not going to be entirely comfortable in the role of ‘Tom’s dad’. But I’m now locked in for the next three hours.

As we barrel through the Flemish countryside, up cobbled climbs and across narrow concrete tracks, what emerges is a story much less superficial than the one I’d envisaged. It’s a story of a bike race, but also one of hard knocks and learning curves, of adventure and friendship, of young dreams and an old hand helping them come true. It’s also about the future of the sport.

Départ

The neutral zone is around five kilometres long. Fensham have drawn the lucky number 1 in the convoy lottery, so we zoom past all the other team cars and slot in behind the race director’s and doctor’s vehicles.

Simon Beldon, an old racing acquaintance, is in the back amid clanking spare wheels: mechanic for the day. He’s one of three support staff who’ve made the trip over from the UK, the other being Giles’ wife, Sonja. Simon’s wife and daughter also came over to watch but have been roped in to help and are waiting with Sonja at the feeding zone ready to hand up bottles. They’re all there on a voluntary basis, giving up their time and energy to help five young riders make what could be a first step towards a career as a professional cyclist.

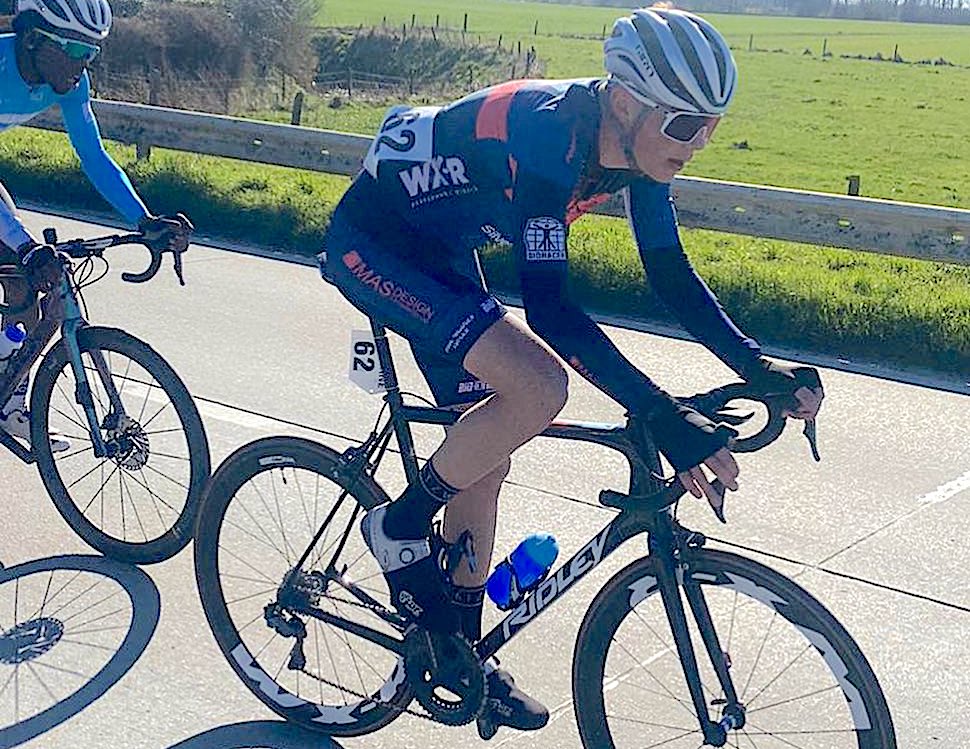

The Fensham Howes-MAS Design team line up as follows for Kuurne-Brussel-Kuurne: Jacob Bush, Alex Beldon, Matthew Brennan, Jed Smithson, Ben Wiggins.

Brennan is a fast finisher, Bush is a lightweight climber, but there’s no real hierarchy or overarching tactical plan. They’re all 16-year-old first-year juniors and what comes next is going to hit them like a ton of bricks.

In the pre-junior youth ranks in the UK, racing is effectively limited to purpose-built circuit-based events, so this is not only their first taste of Belgian racing but also their first taste of proper road racing full stop.

“This just feels like the right place to be,” Pidcock says. “The most important thing for these boys at this stage in their careers is getting the experience and getting noticed. The races with UCI recognition are so vital in that respect.”

Indeed, a glance down the honours list of Kuurne-Brussel-Kuurne juniors proves the point: Remco Evenepoel, Ethan Hayer, and Cian Uijtdebroecks are all among the recent winners.

“Mark my words, some of the kids in that bunch are going to be racing against each other for the next 15 years.”

An early crash

The flag is waved and the race kicks off, although no one succeeds in breaking away for a good few kilometres. The Wielerzone Nederland team are hit by a spate of punctures, and we drive past three of their riders stopping for mechanical assistance in the space of a few kilometres.

“What on earth is he doing just stopping?” Giles exclaims. “I’ve told our lads, if you’ve got a problem, try to keep riding at the back of the bunch and we’ll come to you. If you just stop and stand there waiting, you’ll give yourself too much ground to make up.”

It’s the first in what will turn out to be a long list of hints and tips from an old sage to these fresh-faced youngsters. Talent is one thing – and they all have it – but without this know-how, it will be impossible to apply it. And the only way they’re going to get that know-how is by throwing themselves into this maelstrom right here, and by soaking in everything Giles throws at them.

“Ben’s at the back. Look. That’s him. What's he doing at the back?”

This observation is proved prescient just two kilometres down the road, when Wiggins juts out of the bunch and crashes into a grassy ditch. He’s fine, and back on his bike quickly enough, but the adrenaline is already flowing.

“Some chopper took me out,” he says as he pulls up alongside the car.

“Well you shouldn’t have been at the back then,” Giles barks in instant riposte. “Now get back in and move up!”

Giving back

It’s already abundantly clear that Giles Pidcock has a razor-sharp eye for a bike race, and this one is looking relatively settled as it heads out towards the hills, so it feels like a good time to ask about his background in the sport.

“I used to race all the time growing up, but I stopped doing it seriously after university,” he says. “I’ve stayed involved in the sport in one way or another ever since.”

That involvement has seen him run clubs and teams, coach, and organise races, not to mention driving his sons, Tom and Joe, up and down the country as they made their first steps in the sport.

As for how he ended up here, the Fensham Howes-MAS team had been set up by Yorkshire businessman Neil Hendry but when he decided to step aside in 2019, Giles and Sonja volunteered to step in. Tom and Joe had ridden for the team a few years previously and the Pidcock name has proved a key selling point in terms of getting all-important race invites on the continent.

The team runs on an annual budget of around £30,000, with the funding coming from sponsorships and charitable donations, including from the Rayner Foundation that offers support to so many young Brits. The kit is supplied by Ineos Grenadiers sponsor Bioracer – another perk of the Pidcock name – and the Ridley bikes are supplied on loan by Paul Milnes Cycles, a local bike shop.

“We find we can run a really good system on that budget,” Pidcock says. “We’ll race across the UK in the national series as well as plenty of trips over to Belgium.”

Pidcock doesn’t make a penny from all this, so why does he pour so much of his time and energy into it?

“This sport has given me so much over the years, so many great experiences,” he says. “I feel like I owe it something."

Sticky arm warmers

Crash!

We’re right behind the bunch and it’s clear one of the Fensham riders has gone down. It’s Bush, and Simon is ordered to get out of the car and see if he needs anything. Tangled in the wires of the race radio, it’s anything but a quick service, but the handlebars are eventually bashed back into alignment and Bush is on his way.

Giles was not impressed at the time but soon sees the funny side. “You were like a fat man getting out of a pie shop,” he quips in his Yorkshire drawl.

There’s a problem, though. Bush is off the back and the race is about to hit the first climb. He has taken the opportunity to remove his arm warmers and he’s putting them in his pocket. “Give them to me,” Giles shouts as we pull up alongside.

“I’m good.”

“No. Give, your arm warmers, to me… Right, now hold on to my hand. Hold on!”

It dawns on me that these riders have never had a sticky bottle (or sticky arm warmers) before, and it must be a heart-racing experience. Bush gets a boost into the turn that leads onto the climb, and he’s good uphill so he moves through some dropped riders, but we’re heading downhill on a wide road now and he’s struggling to get back on. He springs out of the saddle on the flat – it’s almost a full-scale sprint – and he makes up ground but the back of the bunch draws nearer and then pulls away, draws nearer and pulls away.

“Times like this I wish I could get out and pedal for them,” Giles says.

Eventually, after 15 minutes of painstaking effort, he regains contact. Giles is relieved, but not so impressed: “He made a right meal of that, didn’t he?”

Planting

The race calms down again as two riders break away from range, and we pick back up on that idea of giving back to the sport. It’s an ethos Tom has clearly inherited from his parents.

“The plan is for this team to morph into Tom’s cycling academy,” Giles reveals. “A bit like Kwiatkowski did with his Polish team. He’s going to invest and use his name to help it grow.

“Tom feels a sense of responsibility to try and make sure younger riders have the same opportunities he did. He got so much support from so many people in the UK and Belgium, and he wants to give some of that back.”

It’s clear his social conscience doesn’t stop at that, either. “Tom’s on a mission to set the world to rights. You know how interested he is in saving the planet," Giles says, referring to Pidcock's support for environmental charities, which recently included a project to plant 1,000 trees.

"We had to plant the bloomin' trees for him," says Giles, clearly immensely proud of his son, but perhaps keen to avoid coming over too soppy. "It was at the cycle park in Kent, which is a) a thousand billion miles away from home and b) built on the old M2 motorway. It was right mission, that. I don’t know what Tom was doing – probably swanning around New York at the time."

Getting back to the serious stuff, domestic racing in the UK has taken a battering in the pandemic, and it was hardly in the healthiest of states before. British Cycling still runs its Academy programme, split between road and track, with nine spots available at junior level.

British Cycling have a five-man team at Kuurne, but in addition there are two independent British teams, with Backstedt Bike Performance – set up by former Paris-Roubaix winner Magnus – also here.

“There are probably about 20 riders in the country at junior level who have the talent to make it as a pro,” Pidcock says. “GB can’t take all the riders who can make it. The Academy is track-focused and might go even more track-focused. My view is we need to work together to make sure that road riders who don’t make it on GB still get opportunities through projects like this.

"There’s some good support out there at junior level, but COVID almost killed off the domestic elite scene, and the U23 scene. It might turn out that a whole generation of riders has been lost and so it's really important, I think, to re-build from the ground up.”

Doing your time

The race is really starting to ignite now as the climbs come thick and fast. We head onto the Kruisberg, and it’s lined with fans. They’re here to see the pro race in a couple of hours but don’t mind roaring these kids up the steep cobbled incline.

For the riders, it’s another reminder of why they’re here and where they’re trying to get to.

“Riders are going pro earlier and earlier these days,” I note.

“Yeah but it’s wrong,” Giles snaps back.

“It might be working out for a few talented guys at the top, but you can’t base a whole development system on a few guys. You need the grassroots. You need them to be able to get this kind of experience, then do it again at the next level. Without this, there is no WorldTour.

“Look at Tom, he did his time. He came here, he moved through the junior ranks, he went to U23, and then he stayed two years in U23. He could have gone WorldTour much earlier but he chose to follow the process.”

That process is one of grounding as much as anything. “Dura-Ace,” Pidcock says, thinking aloud, as we pass a rider on the highest-spec electronic groupset money can buy.

“What’s the point? You get onto a development team and then you’re down on bog-standard Ultegra. It’s not necessary for juniors to have the best gear.”

The Fensham Howes riders are on more modest – but still high-end – bikes, which are provided by a local bike shop in Yorkshire. They return them at the end of the season and they’re sold on at a cut price. One initiative Pidcock has introduced is that the riders put a deposit down on the bikes when they take them out at the start of the year.

"It’s an important lesson. We try to teach them that if they look after their bike then their bike will look after them. Since we’ve been doing that, the bikes have all gone back to the shop spotless.”

Dropped

We’re in the heart of the Flemish Ardennes now. It’s as if those climbs have served as a portal, and now we’re in the rolling countryside, forests rising to our right, towns visible at the end of the sloping fields to our left. Downhill and we hit flatter ground, zig-zagging along 90-degree angles on a warren of narrow roads that slice through this exposed landscape.

The roads are barely wide enough for one car at times, and often lined by deep ditches. We come alarmingly close to ending up in one of them as Giles muscles his way past another team car on the cobbles, and I hold my breath again as he throws us through right-angles bends and brushes past dropped riders, horn blaring.

It’s not hard to see where Tom gets his famed bike handling skills from.

“It’s a bit like riding a bike but without the hassle of pedalling,” he says. “It’s all the things I like: driving and bike racing.”

As I nervously clutch my door handle, I wonder what qualifies him to do this mad activity.

“I guess I’ve spent a lot of time in bike races over the years."

The riders hit the Kluisberg. It’s serious stuff now. Things have stretched to breaking point, with the small breakaway within a minute and attacks pinging from the bunch. As we crest the climb and turn off, Wiggins is right there, off the back. If Bush’s chase earlier in the race felt long, this one will be excruciating.

For the best part of 20km, we accompany this 16-year-old on a brutal journey. He skilfully weaves his way in and out of the various cars, using the convoy to his advantage. When he emerges into the wind, there are big accelerations, but the lactic acid soon rushes back into his legs. He finds company from one or two other dropped riders but he’s not getting any closer.

“He’s done,” says Simon.

“Yeah but if we can just get him back in…”

We pull up alongside Wiggins. “Grab a bottle, Si… Right, Ben, hold onto this and when I say sprint, sprint… SPRINT!”

But Wiggins does not sprint. Instead, he fumbles the bottle into the cage on his bike before eventually bursting out of the saddle, but by then the momentum from the car’s acceleration has seeped away.

“Don’t worry about the fucking bottle!” Pidcock yells. A couple of minutes later, he sees the funny side: “He thought we were actually trying to give him a bottle.”

Despite this misstep, Wiggins is getting closer. He’s mere metres off a small group that could be his lifeboat, with what’s left of the main group visible a few turns up ahead. After 30 minutes of fighting with everything he has, he makes it. He’s not in the bunch, but he’s back in a group for the first time in a long time.

However, it doesn’t last long. The road tilts uphill for another subtle climb and Wiggins is dropped. After what he’s just been through, this is terminal.

“Unlucky mate. Just ride to the finish,” Pidcock says as we pass the forlorn rider.

Three minutes later, the group he was in comes back to the main bunch, which itself reels in the breakaway. That’s the race. It’s a cruel sport.

Never give up

One down, attention turns to the four Fensham riders left in the race with 40km to go. Almost immediately it is back into damage limitation mode. We catch sight of Bush, and he’s been tailed off the back.

“This is getting hard work.”

Bush is given the drafting treatment and makes a better first of the sticky bottle treatment, but he’s clearly suffering. The final climb is coming up, and the lightweight rider manages to steady the ship, but the route soon hits a brutal cobblestone sector exposed to the wind. Pidcock spots that it’s coming from the left and tells Bush to use the cars and keep them on his left.

“You can get back in here! That’s the front of the race! You’ll hate yourself all week if you don’t!”

“He’s gone, mate,” comes the call from the back seat.

“He’s not. We’re not going to let him go.”

But it’s no use. Bush is dropped for good. “Just ride to the finish.”

A few kilometres later, we come across Jari Prins, a Dutchman from the JEGG-DJR team, who was chasing with Bush a while back. He’s still going and still looking strong. Giles and Simon, clearly impressed enough to put aside team allegiances, wind down their windows and roar him on.

A bit further on, we see him regain contact. “Hope he’s not a decent sprinter,” Pidcock jokes, before adding: “That right there is a brilliant example we can give to Jacob. He was with him. Now that lad’s in with a shot of a result. It’s just a lesson that you should never give up.”

Arrivée

The race hits Kuurne for the finishing loop. There’s a group of nine in the lead but the gaps are small and anyone in this sizeable main bunch has a shot at glory. Three Fensham riders remain and have largely flown under the radar given the attention paid to Wiggins and Bush. Brennan is said to be the fastest in a sprint, while Smithson and Beldon are more of all-rounders.

However, in the distance we catch a glimpse of a Fensham rider sprinting off the front, and it’s Brennan. It seems that perceived specialities at UK youth level count for little here.

“Nah that’s good,” Pidcock says when I question the tactics. “I told them all last night, the last hour is going to be full-gas, get involved. He’s getting involved.”

The nine-man group stays clear, and in there is Sente Sentjens. The big Belgian stomps clear and only moves further into the distance. A few kilometres from the finish, it’s clear it’s all over and it’s a deserved victory. With the win out of sight, a spate of attackers clip off the main bunch in a disorganised final few kilometres. We turn off the deviation and head back to the car park, in the dark about how the final kilometre is playing out.

We arrive at the same time as Wiggins, who’s the first to have the post-race chat with Giles. He stays quiet and nods his head. The disappointment is palpable.

“Knackered,” Wiggins says when we ask him how he’s feeling. “Just that first hour… my first junior race, and I forgot to eat. I felt good through the first few climbs but then I just went. Coming out of youth racing, we’ve never had to think about all this before. We were told before the race but when you’re in it and everything’s going on around you, it’s kind of hard to remember everything.”

The riders appear one-by-one. Smithson is banged up on his right side and it turns out he crashed after a touch of wheels. No one quite knows exactly where they finished but the results sheet will have Beldon and Brennan in 38th and 39th in the main group, with Smithson down in 62nd after his crash.

Riders from the GB and Backstedt teams pop over and they compare notes, war stories, exaggerated claims of attacks, plus guesses at just how big that guy who won was.

“It’s so different,” Bush says. “It just ebbs and flows the whole time. The biggest thing was the importance of always moving up. If you’re happy with your position, you shouldn’t be, you can always do more. That’s the biggest takeaway for me.”

There’s no big debrief here, but Giles makes his way around talking to all the riders in turn, listening sympathetically. He’s less animated now, but he chips in with his initial observations and suggestions. In any case, there’ll be plenty to chew over on the long drive back to the UK.

Future

As I walk away, with just enough time to grab one of those sandwiches from the press room before the finish of the elite race, I’m reminded of the story I’d initially set out to find that morning. Tom Pidcock has said himself that he was inspired by Bradley Wiggins, and Ben Wiggins has said that he’s inspired by Tom Pidcock. This is all neat enough but the generational handover doesn’t happen by inspiration alone. It happens because of people pouring their heart, time, and money into making it happen.

At a time when the whole system is creaking and swaying, these people are the glue that’s just about holding it together. Instead of asking where the next Bradley Wiggins is going to come from, we might as well be asking where the next Giles Pidcock is going to come from.

And perhaps that’s the point of all this. The stated aim is, of course, to propel these youngsters to the professional ranks, but it’s not the be-all and end-all. It has become clear that this school is far broader in its scope – no shortcuts, no cheat codes, just a 360-degree grounding in bike racing. If it yields one pro, fantastic, but if it yields two people who properly care about the sport, even better.

The riders stick around for the finish of the elite race, and they watch Fabio Jakobsen triumph in a bunch sprint. Eight years ago, the Dutchman finished 42nd at Kuurne-Brussel-Kuurne Juniors. It’s another reminder of the life that’s up for grabs, but it’s also a reminder of the purpose served by these races and the people that make them happen.

After all, a tree is only as strong as its roots.

Patrick is a freelance sports writer and editor. He’s an NCTJ-accredited journalist with a bachelor’s degree in modern languages (French and Spanish). Patrick worked full-time at Cyclingnews for eight years between 2015 and 2023, latterly as Deputy Editor.