Philippa York and French expectations at the Tour de France

The home nation may not end their long drought in 2020 but they can still dream

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

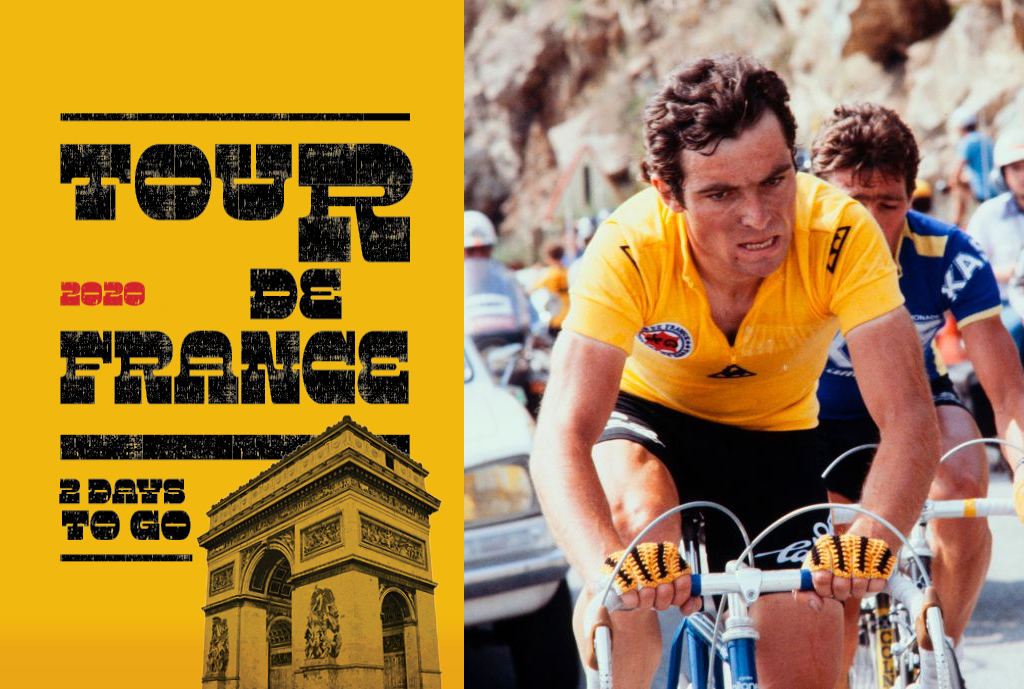

It's been 35 years since a French rider stood on the top step of the podium in Paris, and that's a very long time for a country that sees the Tour de France not just as a bike race but as a representation of everything that's good about France.

The race is more than a showcase that says ‘look how beautiful our country is’. It's so coveted, followed and respected that they don't even need to say where it is as it's simply known as ‘the Tour’. The French like being important.

Understandably then, the home riders are expected to be at the forefront of the race, and it’s even better when they’re resplendent in yellow and hailed as a saviour for national pride in the face of a foreign challenge.

Julian Alaphilippe could have been elected President last summer if they had decided to have a snap election while in the yellow jersey and it's no surprise to find Tommy Voeckler as national coach because being a maillot jaune wearer when you're French is about as good as it gets for a rider.

Only one thing trumps that and it's actually winning the Tour. Alas it's a while since the days of Bernard Hinault and Laurent Fignon back in the 1980s and ever since there's been a succession of potential French riders who could have won but didn't.

Jean-François Bernard and Laurent Jalabert suffered from the pressures and ended up on foreign teams to escape the expectations, and after that it's a story of surprises like Jean-Christophe Peraud suddenly popping up from nowhere.

More recently the focus has appeared on two names that the home public can cheer for to stimulate their dreams of glory again: Thibaut Pinot and Romain Bardet.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

These two have swapped places in the minds of the French media as the one who might since 2013, with Pinot being the more spectacular but Bardet ultimately bettering that by being a more regular visitor to the front of proceedings.

However they aren't the characters that Hinault and Fignon were; they're not as arrogant or dominant or on occasion downright rude as the last two French winners could be, and so their relationship with the public has more warmth and compassion to it.

Hinault wanted to crush his rivals and though the French public like a winner they also quite like just a touch of humility too. The Breton badger only discovered that in his last year or racing and even then there was the feeling that it was through gritted teeth rather than being his natural tendency. Hinault was respected and admired for his dominance but I don't think he was taken to the hearts of the public until many years later and he had stopped pinning on a race number.

Laurent Fignon, on the other hand, had some more likeable traits but he was Parisian and not from the peasant stock that had been the staple supply chain for most of the previous great French champions, so he was always compromised in how much love he received.

Much like Jacques Anquetil, he was seen as something of a calculated bike rider, who was too educated and appreciative of the good things in life to be a bike rider. The French like their heroes to be slightly flawed. Sometimes they even like them despite them not ever winning the Tour hence the popularity of Raymond Poulidor.

It's been so long since a Frenchman won the Tour that even the mere hint of one of them pulling it off brings the national to an almost fever pitch level of rejoicing.

And that's the dilemma that Pinot, Bardet and even Guillaume Martin now face when they line up in Nice on Saturday with the hopes, expectations and prayers of a nation wishing that they might end the drought that is hanging over cycling in France.

A home victory for the French would be a massive thing to happen, in a similar way to the reaction in Britain when Bradley Wiggins became the first British rider to win the Tour de France and then go onto Olympic success in 2012.

Imagine that but amplified a few times more and that's the impact a French win would have.

Instantly there'd be more people out riding, more interest from sponsors and French industry to be involved not just in cycling but in all sports. There'd be no more complaining about the dreariness and the complications of normal life because they would have won the Tour and everything else would be forgotten for a while.

The French are known for their love of culture but they love sport too and the Tour allows them to indulge in both, that's why Pinot, Bardet and Martin become so important.

They are carrying not only their dreams but also the dreams of a nation, so it's understandable how each of then reacts to that pressure.

When you look at Thibaut Pinot's Tour participations it's apparent if everything falls into place then good things happen. However these last couple of years he's been convinced by the enthusiasm of team boss Marc Madiot that he can, he ought to and he will win a Tour de France and that it's just a matter of circumstances and being in the right place at the right time.

He's talking himself up more too but there's always that feeling with Pinot that he's like a thoroughbred race horse, chomping at the bit; can't wait to go fast; and then it's either very spectacular or ends emotionally.

Romain Bardet isn't quite the opposite but he definitely looks frailer, which belies his results at the Tour as he's been way more consistent than Pinot and way more successful with two appearances on the podium in Paris.

However, the expectations have been getting to him and though he's still winning stages and last year’s Mountain classification, the fact that he's moving away from a French team say that he's had enough of the pressures of being one of the French hopes. A hardly stellar Dauphine which was essentially a mountain climbing test showed he isn't up there with Roglic, Bernal and Pinot and that can't be good for his sometimes fragile morale.

The Dauphine did produce another name to add to the potential home grown winners, so step up Guillaume Martin of Cofidis.

Third place overall at the Dauphine when all around him fell or failed, confirmed the steady progression of his career despite being part of Wanty Group-Goubert until 2020, who aren't exactly known for their stage racing credentials.

Entering into what could be his best years, this could be the time when Martin improves again and continues on a path that has seen him finish his first Tour de France in 23rd spot, the second in 21st and last year in 12th position.

That seems to say he's figuring it all out and doing the right things. Now he and the other French hopefuls have to deal with the pressures and focus of their own ambitions and a nation's dreams.

Philippa York is a long-standing Cyclingnews contributor, providing expert racing analysis. As one of the early British racers to take the plunge and relocate to France with the famed ACBB club in the 1980's, she was the inspiration for a generation of racing cyclists – and cycling fans – from the UK.

The Glaswegian gained a contract with Peugeot in 1980, making her Tour de France debut in 1983 and taking a solo win in Bagnères-de-Luchon in the Pyrenees, the mountain range which would prove a happy hunting ground throughout her Tour career.

The following year's race would prove to be one of her finest seasons, becoming the first rider from the UK to win the polka dot jersey at the Tour, whilst also becoming Britain's highest-ever placed GC finisher with 4th spot.

She finished runner-up at the Vuelta a España in 1985 and 1986, to Pedro Delgado and Álvaro Pino respectively, and at the Giro d'Italia in 1987. Stage race victories include the Volta a Catalunya (1985), Tour of Britain (1989) and Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré (1990). York retired from professional cycling as reigning British champion following the collapse of Le Groupement in 1995.