Peter Sagan's triple: Three years on top of the world

A look back at the Slovakian's record-breaking World Championships run

This year, Cyclingnews celebrates its 25th anniversary, and to mark such an important milestone, the editorial team will be running 25 pieces of work that look back at the sport over the last quarter of a century.

Here, we take a look at Peter Sagan, one of the biggest stars of modern cycling, and his unprecedented achievement in winning the World Championships road race back-to-back-to-back from 2015 to 2017.

Run down through a list of men's road world champions and you'll find a number of multiple time winners – 12 of them, in fact. Paolo Bettini and Greg LeMond are among the two-time victors, while five men have donned the rainbow jersey three times.

In 2017 in Bergen, Norway, Peter Sagan entered that select group, joining Alfredo Binda, Eddy Merckx, Rik Van Steenbergen and Óscar Freire as the only men to win three Worlds road races in 84 years of the event. What separated them was Sagan's feat of taking the rainbows three times in a row.

Several men – Ronsse, Moser, Argentin, Bugno, Freire – had come close before Sagan, but the Slovakian star's winning run has no parallel, and remains one of the greatest achievements of the past 25 years of the sport.

We'll take a look back at that historic run, going through the races themselves in Richmond, Doha, and Bergen, as well as the context of the wins within Sagan's career.

The build-up to Richmond

Sagan was, of course, already a superstar of the sport long before he'd donned his first rainbow jersey, piling up 74 wins – 31 of them in the WorldTour – during the first six years of his career after exploding onto the pro scene as a neo-pro prodigy with two stage wins at the 2010 Paris-Nice.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

By the 2015 Worlds, he had four Tour de France green jerseys in his cupboard to go with four stage wins at the race and at the Vuelta a España, while Classics wins at Gent-Wevelgem in 2013 and the E3 Harelbeke in 2014 were among other notable successes, which also included a long list of stage wins at the Tour de Suisse and Tour of California.

Although already a top sprinter and Classics rider by 2015, Sagan did have something of a reputation as a nearly-man at the biggest races of them all. There were fourth and fifth places at Milan-San Remo and the Tour of Flanders in 2012, followed up by a pair of second places the next season, and then sixth at Paris-Roubaix in 2014, while his Worlds outings in Copenhagen, Limburg and Tuscany from 2011 to 2013 saw him take 12th, 14th and sixth.

His 2014 Tour green jersey came after four second places and four more top-five placings, but by the time he kicked off his 2015 season, the 25-year-old hadn't tasted victory since his National Championships road-race win back in June.

Sagan would break his duck at Tirreno-Adriatico that March, following a pair of runner-up spots apiece there and at the Tour of Qatar. His win in Porto Sant'Elpidio was the first of his time at Tinkoff-Saxo, with a reported €4 million contract the reward for his exploits at the folding Cannondale team.

"How many second places did I get? 15 or something? That's a lot…" he said after that win. "First would have been better. But I took not winning as experience for life: sometimes you are up and sometimes you are down. That's life, it's OK."

Once again, though, he played the nearly-man at the Classics, taking fourth at San Remo and Flanders before a broken shifter put paid to any chance of success at Roubaix.

The results signaled the start of a fractious relationship with team boss Oleg Tinkov, who said he was "not super happy" at the winless Classics campaign, adding that "there is never enough pressure" on his riders to perform.

The following month, the Russian only added to the polemica, writing in his Cyclingnews blog: "Peter is a difficult case. It seems he's lost something." Sagan duly replied with two stage wins and the overall in California, including that famous performance on Mount Baldy.

Wins in Switzerland and a double at his National Championships meant a successful build-up to the Tour, but once again he fell short of victory in France, taking five second places and six further top fives en route to yet another green jersey.

Tinkov's response? "I've actually got mixed emotions… He was no doubt the strongest guy… I just wish he'd won at least once."

Sagan's Vuelta saw him grab that victory, beating Nacer Bouhanni and John Degenkolb in Malaga on stage 3, although his race would be cut short just six days later. It wasn't a planned abandon as was the case a year earlier, though, but one caused by a race motorbike that hit him while attempting to pass the peloton. Not an ideal build-up to the Richmond road race just 28 days later…

Victory in Virginia

Sagan had suffered bruises and contusions in the crash, but thankfully no fractures before the trip to the USA. However it was also far from what he had planned ahead of his sixth crack at the elite road race. Training camps in Colorado and Utah would follow, although he'd head to Richmond uncertain of his form.

A disastrous team time trial for Tinkoff-Saxo a week before the road race certainly wasn't in the plan, as Mick Rogers and Michael Valgren crashed early on and a potential medal challenge ended with the team finishing last, over eight minutes down.

The duo avoided broken bones, while Sagan had a lucky break too, avoiding the carnage. Perhaps swayed by superstition, he studiously avoided talking himself up in the days before the race, and wouldn't name any other rider, either.

"It doesn't matter what I can see or not because it's just losing time," he said. "Every year is different, and every year it's been not the favourite riders. I think it's for nothing, thinking about the favourites."

Come the race, and Sagan was a quiet figure, hidden away in the peloton for much of the 260-kilometre battle. He had only two teammates – Michal Kolar and brother Juraj – for company, making for a relatively weak Slovakian team against the nine-man powerhouses of the likes of Belgium, Spain and Italy.

"We are not a national team for making the race, no?" he said before the race.

Moves came and went at the front of the race, with stronger nations controlling the peloton and the likes of Tom Boonen, Michał Kwiatkowski and Bauke Mollema jumping away three laps from the finish.

Entering the final lap of the Flandrian-style finishing circuit, which included the part-cobbled climb of Libby Hill and the steep ramps of 23rd Street and Governor Street before a false flat finish, that powerful group was caught as Tom Dumoulin led the way up front, while Italy also charged down a number of late attacks.

With three kilometres to run, Sagan made an appearance, stuck on Greg Van Avermaet's wheel as the Belgian powered his way onto Libby Hill and the peloton split behind. Sagan quickly moved to the front, putting clear air between him and fellow Classics specialists Van Avermaet and Zdenek Štybar over the top.

It was the decisive move of the race. Over the remaining two kilometres, there was nobody that could come close to Sagan. The challengers behind faded into the charging peloton, but Sagan held his advantage, riding in an aero tuck down the descent and draping his hands over his bars on the flat run to the final hill.

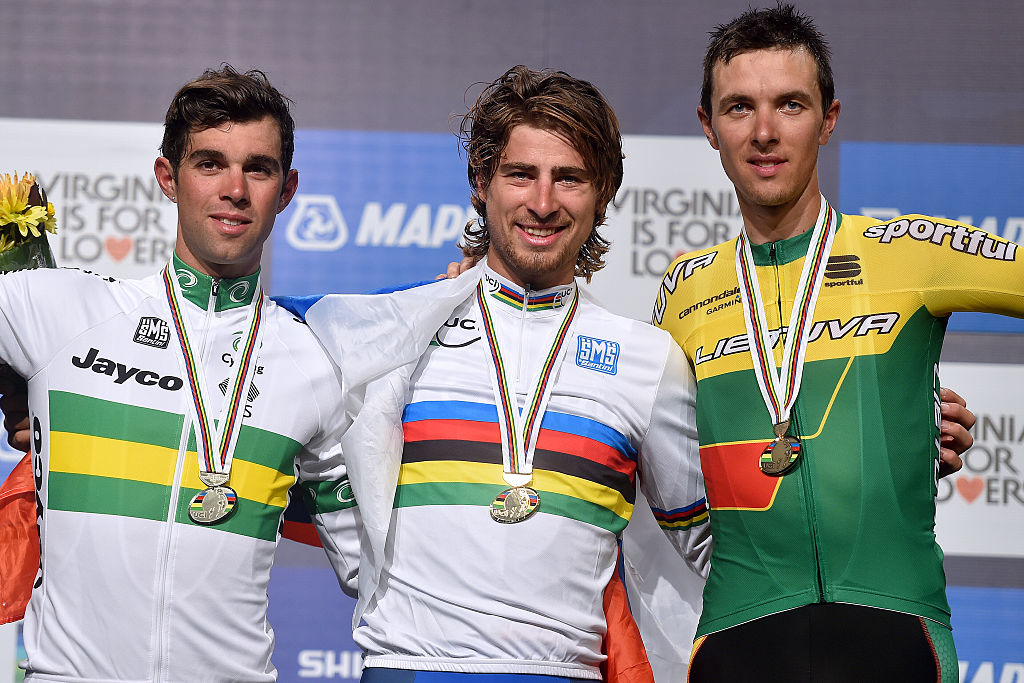

The run to the line was a coronation, as Sagan pushed on along the false flat, sitting up to celebrate 25 metres out as Australia's Michael Matthews led the sprint for second, three seconds back. After the criticism, the near-misses, and the moto crash, he had done it.

In the mixed zone immediately after his win, nestled among the thanks to his teammates and evaluation of the finale, Sagan took the time to cite the refugee crisis in Europe as his motivation for the race.

It was a somewhat unexpected topic to bring up after the biggest moment of his career, but showed a gravitas and sensitivity that isn't always apparent, as well as a desire to use his platform to inspire change.

"I was finding motivation in the world," he said. "I think it's a big problem in Europe. I want to just say this was a very big motivation for me… I just want to say to all the people: change this world.

"I wanted to tell because I don’t see inside the politicians on this stuff. But I wanted to tell about the people because I was thinking about it and how we can change the world.

"One man is nothing, but we are more. We can change. It’s about the future. I am very happy for this, but I want also for another generation to be here."

A second in the sands of Qatar

In contrast to a 2015 campaign that was tough for Sagan, his 2016 was vintage – arguably his best year on a bike so far, and a riposte to the idea of a 'curse of the rainbow jersey'.

Following his win in Richmond, he took to his role as world champion to speak once again about the refugee crisis and global warming at the Abu Dhabi Tour. Meanwhile, at the UCI's end-of-season gala, he was in his signature playful mode, wearing a leather jacket to the black-tie event and breaking the glass on his framed rainbow jersey to don it for photographs at the end.

The start of his 2016 season was once again full of top placings, including second at the Omloop Het Nieuwsblad and fourth at Strade Bianche after sparking the winning move – although once again Sagan would have to wait to win.

Those wins, when they came, were big. Sagan followed a second place at the E3 Harelbeke with his second Gent-Wevelgem victory, beating a small group including Sep Vanmarcke and Fabian Cancellara to the line. Less than a week later, he was once again on top of the world, soloing to his first Monument victory at the Tour of Flanders amid transfer-market rumours after Tinkov had announced his pulling out of the sport at the season's end.

Fate conspired against him at Roubaix, but more wins came in California, Suisse, and – most importantly – the Tour. Three stages in yellow early on were accompanied by three stage wins after a two-year drought – including a thriller in the wind in Montpellier – as well as his fifth green jersey.

By the Tour's end, focus was already on the Rio Olympics – where he'd race in the mountain bike cross-country – and a Worlds defence, with Tinkov by that point striking a different tone: "I believe he is the best cyclist in the world. It makes my decision to close the team even harder."

There was a different route to the Worlds, too, coming via wins at the GP Quebec, the inaugural European Championships, and the Eneco Tour, where he sealed a WorldTour rankings victory.

Come the Worlds, which had been bizarrely awarded to Qatar four years earlier, and Sagan was once again among the top favourites, although a pan-flat 257.5-kilometre course (which was, for the most part, devoid of spectators) would favour purer sprinters such as 2011 world champion Mark Cavendish or Marcel Kittel.

As was the case in previous years, Sagan only had two men – Juraj and Kolar – with him up against the might of the nine-man sprint squads other countries could employ, and once again he kept quiet for the vast majority of the race, staying out of trouble and saving energy for the final.

Belgium were particularly active, putting the hammer down in the crosswinds to split the peloton in the opening 100 kilometres, a move that Sagan said he was the last man to get across to.

But with the remainder of the race posing fewer obstacles, it was all on the nailed-on sprint finish. Italy led the way in the final kilometre, hoping to launch Giacomo Nizzolo, while the likes of Sagan, Cavendish, Michael Matthews and Tom Boonen lurked further back.

Sagan was on Edvald Boasson Hagen's wheel when the sprint was launched from just over 200 metres out, and jumped down the right up against barriers as the top sprinters spread across the road. To the left, Cavendish was bursting past Matthews as Sagan outdragged Nizzolo and Boonen, the pair meeting in the centre metres before the line.

The victory, though, was clear. Sagan had beaten Cavendish, winner of 30 Tour de France sprint stages, including four earlier that year, in a flat-out sprint. If his win on the short, sharp hills in Virginia a year earlier was impressive, then this was equally so, albeit it in a different way. Sagan had won the lottery of the sprint, he said later.

"In the end, I said we'd go for the sprint and it was a lottery for sure. I started sprinting on the right side and I was lucky they didn't close me on the right side. It was a lot of good luck for me, I think maybe destiny. It doesn't happen every day that you can sprint like this," Sagan said.

"You never know what's going to happen in a sprint, especially one like this with a lot of sprinters in the group. What wheel are you going to choose? It's always a lottery, something can happen, so you just go to do your best. I had nothing to lose.

"I thought to myself it would be stupid to attack and I decided to go for the sprint. If I was first, second or 10th it didn't matter, I had nothing to lose. It just happens. It's very strange but I'm very happy."

Number three in Norway

With 2017, his second year in the rainbow jersey, came a new team for the second time in his career. Bora-Hansgrohe was the destination, the German team moving up to the WorldTour and making a splash with it as they signed up Sagan as well as his Tinkoff teammate, Grand Tour leader Rafał Majka.

Despite the big changes, Sagan's goals for 2017 remained the same – Monuments in the spring and the green jersey in July – but unlike 2016, the year wouldn't be an annus mirabilis. A Kuurne-Brussel-Kuurne win and two stages at Tirreno-Adriatico signalled a strong start, but his main goals of the spring came undone one-by-one.

He made the race at Milan-San Remo with an attack on the Poggio but lost out to Michał Kwiatkowski at the finish, crashed at the E3 Harelbeke, lead the peloton in for third at Gent-Wevelgem, crashed out of the chase at Flanders after snagging a spectator's jacket, and suffered several punctures at Roubaix.

Despite the now-customary wins in California and Suisse, the Tour didn't get much better, either. He took his eighth win on stage 3, but was out of the race the next day, disqualified after edging Cavendish into the barriers in Vittel, his bid for a fifth green jersey swiftly over.

After leaving the Tour under protest, he once again took a different route to the Worlds, which for 2017 would be held on a hillier course in Bergen in western Norway. He was back to winning ways at the Tour de Pologne and BinckBank Tour, also knocking out the GP Québec once again.

While Sagan may not have enjoyed the sparkling year he did in 2016, he was heading into the Worlds in another rich vein of form, although an illness suffered shortly beforehand saw him miss the TTT and downplay his chances of a historic third title in a row.

Slovakia's rider allowance of six – still including Juraj and Kolar – would help, though. It was once again a waiting game for the reigning champion, hiding in the shadows somewhere near the rear of the peloton over the 12 laps and 267.5-kilometre course.

There were splits when Julian Alaphilippe and Gianni Moscon attacked 10 kilometres out over the Salmon Hill climb, and for a time it looked as though the Frenchman could be on to a winner, even as attacks flew behind.

Sagan was in the chase group, although it was Denmark and Italy leading the chase as Moscon was dropped five kilometres out. Alaphilippe was eventually caught before the final kilometre, as was a late attack by Magnus Cort, and then it was all up to the sprinters.

Just like in 2016, Italy led things out, while Alexander Kristoff sat on Alberto Bettiol's wheel, with Sagan in a much better position than the previous year, sat directly behind home favourite Kristoff.

In the end, it was a two-man shootout for the win, with the two Classics men-slash-sprinters pushing each other to the line. Once more it was Sagan, just about edging it on the line. Not that he had a plan – Sagan said afterwards that he thought he'd be racing for fourth or fifth.

And as in 2015, he had a message to deliver, even in the wake of his unprecedented achievement, dedicating the victory to Italy's Michele Scarponi, who had died earlier that year after being hit by a driver while out training.

"He was a special person, not only in cycling but in the world. He was always smiling and always gave off positive energy.

"I'm not sure if it will change anything in the world but it's nice," he said of his third title.

"Every World Championships that I won is special. They're different: different parcours, different city, different style of race, but the title is always the same and every moment from each race is really special.

"The first one was not expected, the second for sure was not and this time everyone expected it up front, but it was not easy. It was a special day.

"Even if it's 267km, you have to move just once; you can attack, go in the break or sprint. What do you do? Until the last kilometre, we didn't know if it was a sprint. That's why it's special."

And that was that. Since that day in Norway, Sagan has raked in more big wins – Paris-Roubaix, a third Gent-Wevelgem, four more Tour stages, and two more green jerseys among them – but they're undeniably becoming scarcer as the years pass.

Today, debate rages about Sagan, about his abilities and his desire, and whether he'll again hit those soaring heights as he did in 2016.

The moments of magic still come – you only have to rewatch his solo Giro stage win in Tortoreto to see that – but even if they're ever rarer, and whatever lies in store for the 30-year-old, that Worlds triple will forever be in the history books.

Cyclingnews at 25

How the internet and EPO changed the reporting of professional cycling

25 cycling personalities of the past 25 years

After the gold rush: The rise and fall of the Tour of California

Burst bubbles and blurred lines: British Cycling, Team Sky, and the cost of success

Fuente Dé: Contador's Revolution

Mark Cavendish: From fat banker to sprinting GOAT

The Marianne Vos effect: 2012 Olympics-Worlds and the elevation of women's cycling

When the Tour de France meets Paris-Roubaix

'It's real, mate' – When Hayman conquered Boonen at Paris-Roubaix

Behind the scenes: How Cyclingnews reported on the Genevieve Jeanson story

The 25 most memorable races of the last 25 years

Feed the beast: Covering Lance Armstrong for Cyclingnews

'Happy New Year. When you want, I'll begin' – The moment Miguel Indurain retired

'No further information available': ONCE, McEwen and the 1995 Mount Buller Cup

Dani Ostanek is Senior News Writer at Cyclingnews, having joined in 2017 as a freelance contributor and later being hired full-time. Before joining the team, she had written for numerous major publications in the cycling world, including CyclingWeekly and Rouleur. She writes and edits at Cyclingnews as well as running newsletter, social media, and how to watch campaigns.

Dani has reported from the world's top races, including the Tour de France, Road World Championships, and the spring Classics. She has interviewed many of the sport's biggest stars, including Mathieu van der Poel, Demi Vollering, and Remco Evenepoel, and her favourite races are the Giro d'Italia, Strade Bianche and Paris-Roubaix.

Season highlights from 2024 include reporting from Paris-Roubaix – 'Unless I'm in an ambulance, I'm finishing this race' – Cyrus Monk, the last man home at Paris-Roubaix – and the Tour de France – 'Disbelief', gratitude, and family – Mark Cavendish celebrates a record-breaking Tour de France sprint win.