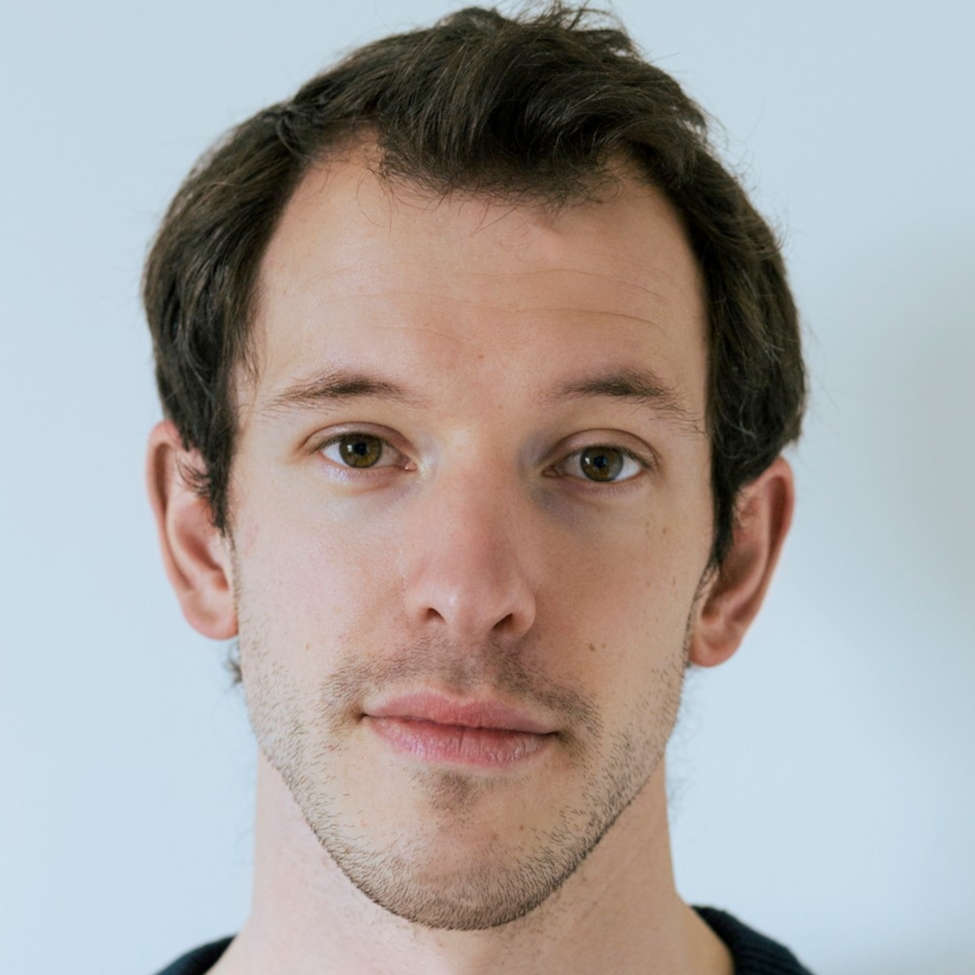

Pedal performance: How Matteo Jorgenson re-learnt the art of pedalling

When the American moved to Visma-Lease a Bike, he knew the superteam's big budget would accelerate his development, yet he didn't plan on having to re-learn how to pedal

When Matteo Jorgenson moved to Visma-Lease a Bike from Movistar at the end of 2023, it was a step-up in budget, all-around team quality and attention to detail. A driven master of self-improvement had found his perfect match, quickly going from promising talent to one of the peloton’s stars.

There are umpteen factors behind the rise of Jorgenson, such as more focused altitude camps, a FoodCoach app with tailored nutrition, eye-catching aerodynamic helmet gains and more wind tunnel testing. No stone was left unturned in driving performance gains and helping the American to become a Dwars door Vlaanderen winner and two-time Paris-Nice champion.

But there was one drastic, surprising change at the start of the process which has made a “world of difference” to the American ace – re-learning how to pedal.

"After I’d signed with this team, they sent me to their biomechanist who lives in Bilbao," Jorgenson told me for Alvento in October 2024. "He basically sat me down with this footage from the Tour de France he’d captured of me and was like ‘your pedal stroke is one of the least efficient I can find. We can improve this if you invest in this.'

"‘You have to want to change it because it’s going to be really hard and annoying to do so. You have to break this muscle memory that you have. If you can do that, you’re gonna make huge strides in which muscles you’re firing at certain times’. Because I spent 18 years, or whatever, pedalling in a certain way."

Cyclingnews understands Jorgenson worked with leading bike fitter and biomechanist Jon Iriberri, a consultant to the Dutch team for over a decade, though the Spanish expert did not respond to several requests for comment. Visma-Lease a Bike confirmed they work with Iriberri on a freelance basis, but indicated they "never have interviews with experts on specific domains."

Receiving that advice was a shock to Jorgenson’s system. "I didn’t believe him. It was horrible, terrible. For a while, I denied it – I can’t be this good if you’re telling me that I’m losing that much," Jorgenson recalls, smiling.

There is potentially a lot to be gained from improving one’s pedal revolutions and the torque generated. Iriberri told Road.cc in 2024 that there is a performance gain area of seven to eight percent to be made.

The biomechanist put Jorgenson’s foot on an indoor trainer and took it around the pedal stroke at certain angles for an hour to show him where gains could be made.

It took the American the rest of the season with Movistar and the 2023 winter to work at it and get his calves strong enough to adapt to the new technique. Ultimately, the most efficient pedal strokes are principally down to good genes and strong hip, hamstring and knee angle ranges, as well as regular strength and conditioning work.

What happens when we pedal?

Using the clock face analogy for convenience, torque can be made from one o’clock down to five o’clock on a pedal stroke.

The quads and glutes, two of the body’s strongest muscles, supply around two-thirds of the power. They drive the downstroke while the calf, ankle, and foot subsequently transfer power to the pedal. As the foot travels towards the bottom of the pedal stroke, the hip extends and then flexes as the foot returns to the top.

During winter, I visited the London studio of Cyclefit, industry leaders with decades of experience who fit numerous pro cyclists to get deep into the science of pedalling and performance.

An hour before my visit, they had a leading WorldTour pro cyclist (who will remain anonymous for privacy reasons) through their doors for a fitting.

Co-founder, bike fitter and author Phil Cavell talked through optimal technique using camera footage of the cyclist and their Polar View graph up on screen, which measures the force being put out.

It’s easy to assume that professional cyclists are among the best at the repetitive act of pedalling. As Jorgenson’s example shows, that’s not true, but this specimen was more efficient.

"What you want is congruency of function and masses of torque around maximum mechanical advantage from the crank at 90 degrees," Cavell says. "The power comes on, it hits that 90-degree mark [of maximum torque] - bang! - massive amounts of torque, then just let it cascade off."

"Then there’s a gap, then bang, on the pedal stroke. All the power is in extension and virtually nothing in inflection. All in the downstroke, nothing in the upstroke...he’s producing power in a staccato fashion, which is exactly what you want."

Cavell explains it should be functional, not just in the power being produced, but ideally with a 50-50 symmetry: this rider’s left and right pedals were mirror images of one another.

Chasing perfection in an unnatural act

Is there a perfect pedal stroke? "There’s a perfect pedal stroke for each individual, in the sense [that] there’s a pedal stroke which doesn’t give that person a problem," Cavell says.

Easier said than achieved: harking back to human beings evolving as bipedals, we are best on two feet, not dropping 'wattbombs' on two wheels. Our quads, glutes and calves are dominant, but more accustomed to producing power in the toe-off phase, in extension.

"Pedalling is very different to running and walking, and it's very difficult for people to maintain good pedalling at 95rpm at 360 watts," Cavell says. "Because there's no resemblance to running tempos whatsoever. So it's very difficult to propriocept those actions, and not propriocepting them properly is a big cost. Because suddenly, you back yourself into dysfunction."

If you see a rider fighting the bike or with their knees sticking out, it usually correlates to bodily adaptations to a sub-optimal setup.

Of course, pedalling technique is just one piece of that puzzle when it comes to expressing optimal power. One’s bike position plays an essential role and that also factors in upper body position, Q factor, foot position, saddle height and angle, seat tube angle, crank angle and handlebar height, shoes and orthotics.

Matteo Jorgenson’s successful amendments underplay the difficulty of changing this cycling fundamental. Employing different muscles takes months of patient strength and conditioning work to elongate ranges. "We’ve worked with pro athletes sometimes who have less [hip range] than my mum, because she does yoga," says Cavell.

Making adjustments taxes the mind as well as the body. Detraining the motor pattern is difficult, given that pedalling is a repetitive act most cyclists do without thinking. Single-legged pedalling at a slower revolution can help to rework it.

The shorter crank revolution

Crank length should generally be proportionate to leg length, but 170mm cranks used to be the go-to for leading racers, with relatively little thought given to them. In recent years, there has also been a micro-revolution in going shorter.

Lidl-Trek star Lizzie Deignan went down to 165mm ones back in 2020, looking to alleviate hip issues. Many Visma-Lease a Bike team members, including Jonas Vingegaard, have also adopted shorter cranks, between 150 and 165mm, influenced by the expertise of Jon Iriberri. Tour de France champion Tadej Pogačar switched to 165mm cranks from 170mm in 2024.

"Most pro riders now shorten cranks to control these angles, so they’re not trying to produce huge amounts of power in an aero position with very compromised hip and knee angles," Cavell says. "What they lose is a bit of torque because power [watts] is torque times revs [cadence] – reduce the crank length, you reduce the torque. But you make up for it in the fact that the pedal cycle is smoother, so you can pedal a bit faster."

There are gains to be made in terms of sustainable power during a six-hour race, marginally-improved aerodynamics and greater injury avoidance.

"You’re not losing any power because you start to get a niggle, pain or a problem, or you start adapting your pedalling around something," Cavell says. That’s pretty important when the average competitor will do approximately 1.5 million pedal strokes during a Grand Tour.

Different strokes for different folks

Tadej Pogačar is an interesting case study, possessing both fearsome power and excellent pedalling efficiency.

"Because his technique is completely special," Lidl-Trek biomechanist Aurelio “Yeyo” Corral, who worked with Pogačar at UAE Team Emirates, says.

The Spaniard says that there is a particular method that Pogačar employs, where he can go up very fast from his downstroke with his ankle.

"In that small degree, from 180 to 200 of the crank angle, when it is down and coming back, if the rider is able to push, not pull, the pedal efficiency increases a lot. And Tadej is one of the riders who is able to push a little bit more at the end of pedalling," says Corral.

Able to open his hips, fluid Pogačar uses slightly less energy than many other riders for the same amount of power.

There are also different pedal strokes for different folks. GC riders, chasing a long-term goal and at the front over Grand Tour mountains for days at a time, need to save as much energy as possible. Shorter cranks help with such efficiency, due to staying seated.

"But for example, strong riders who need to push high watts for a short time - sprinters, Classics riders. If you reduce the crank [length], you increase efficiency, but you lose the torque. Maybe you’re winning in one thing, but losing the key capacity to create high power. So it depends on the rider."

It is about achieving a balance rather than prioritising smoothness at all costs. "I analyse a lot of [amateur] riders in my lab [Macrociclo] with very high values for efficiency but no performance because they don’t push watts," Corral says.

"Efficiency is very important, for sure, but sometimes it’s better to lose efficiency and win effectiveness. The capacity to push faster, stronger."

Corral has seen a range of efficiency values in pro cyclists during his long career in the WorldTour, even riders with around 50 percent of normal values who are able to win prolifically. “It’s not all about efficiency,” Corral says.

Pro cycling’s smooth operators

Souplesse is one of the most pleasing words in the professional cycling lexicon. The French term, meaning ‘suppleness’, describes a powerful, aesthetically-pleasing pedal stroke, with an upper body in harmony.

Hear that word and the mind’s eye may fill with champions of yesteryear and their graceful rotary actions: Fausto Coppi, Stephen Roche, Frank Vandenbroucke, Bradley Wiggins.

However, the way great cyclists pedal has evolved over time and just because it looks smooth as butter does not necessarily mean it was totally functional.

"There was all this ankling," Cavell recalls. "Jacques Anquetil: Everyone loved the way his ankle moved, but he wouldn’t get started now. Flapping around in space, he wouldn’t be able to follow Pogačar for 15 seconds."

The ankle ought to remain neutral without excessive movement. "Nowadays, pro cyclists don’t move their ankles, they’re fixed at 15, 16 degrees and off they go," Cavell says. "They haven’t got time to: they’re producing huge amounts of power."

Cycling legend Bernard Hinault used to race with 172.5mm or 175mm cranks, disproportionately long given he stood at 5ft 8in.

Looking at his palmarès, that gambit did his results no harm but likely increased the closed angle of the knee and hip joints at the top of the pedal stroke, and, subsequently, his risk of injury.

"They pedalled around the problem, basically in spite of the equipment, because now it’s all tweaked to the individual," Cavell says.

That is certainly the case for Matteo Jorgenson, given the conscientious backroom at Visma-Lease a Bike. In the last 18 months, he has shown himself able to perform in a week-long, weather-beaten stage race and a spring cobbled Classic.

You might think months of fine-tuning his pedalling style would be draining, but Jorgenson seems energised by recounting the anecdote. After all, pedalling gains are just the tip of the iceberg for a young rider driven by self-improvement.

"There are a million things," he said. "If you’re open to learning in this sport, you realise that everything matters in your whole life, actually. Your sleep, your nutrition, how much stress you have on a daily basis, if you’re happy at home. I think I try to just add a layer that I can and maintain all the other ones."

If you subscribe to Cyclingnews, you should sign up for our new subscriber-only newsletter. From exclusive interviews and tech galleries to race analysis and in-depth features, the Musette means you'll never miss out on member-exclusive content. Sign up now

Formerly the editor of Rouleur magazine, Andy McGrath is a freelance journalist and the author of God Is Dead: The Rise and Fall of Frank Vandenbroucke, Cycling’s Great Wasted Talent

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.