One for the money, two for the show

So Paolo Bettini is champion of the world and Italians are happy. It's about time because decades...

Tales from the peloton, September 26, 2006

Paolo Bettini proudly waved his homeland's flag after being crowned world champion in the Elite Men's Road Race last weekend but, as Les Woodland recounts, patriotism at the worlds hasn't always been on the forefront of competitors' minds.

So Paolo Bettini is champion of the world and Italians are happy. It's about time because decades can pass without Italy being wholly content about what goes on at the world championship. Either the wrong man won, or the right people rode for the wrong man, or an Italian didn't win at all. But believe me, this is nothing compared to how it used to be in France.

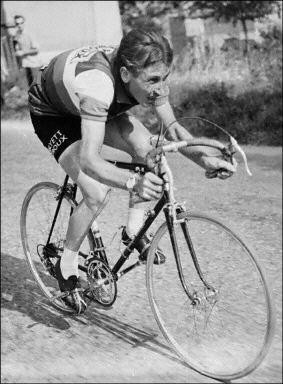

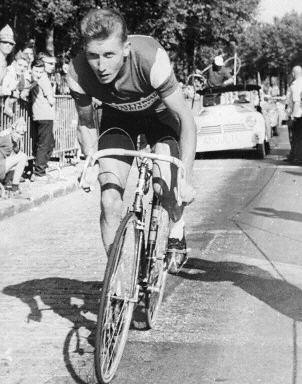

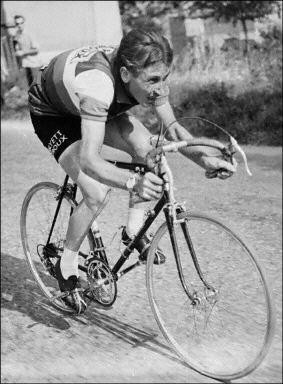

Fast-wind back 40 years. There are still good Italians but the focus of international cycling is further north. Belgium has the classics winners and big sprinters, like Rik van Looy, and a rising talent in Eddy Merckx. France has the Tour winner, Jacques Anquetil, and his perpetual runner-up, Raymond Poulidor.

Time and again, the French enrolled Anquetil and Poulidor for the world championship without either of them winning. Poulidor won widely-spaced bronzes - two of them - and a silver, but Anquetil never once stood on the rostrum... until 1966, when he stood in second place with Poulidor beneath him.

And yet either man should have won. And Poulidor would have had it not been for Anquetil. If you think it smells of skulduggery, you're dead right.

The race was on the Nürburgring car circuit in Germany. Poulidor and Anquetil were at the height of their duelling in the Tour de France and their hostility was as personal as it was professional. Anquetil disliked Poulidor more than Poulidor disliked Anquetil but the war was real enough that for a while the pair would communicate only through their wives.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Come the world championship, both men were in the winning break. They had dropped the local favourite, Rudi Altig, who had come second in the same race the year before. But neither Frenchman was going to cooperate with the other to ensure their break stayed away, still less that one or the other should win the championship of the world.

As the break faltered, up from the back came that same Rudi Altig, better than either of them in a sprint finish. More worrying than that was that he was being towed by another Frenchman, Lucien Aimar. Altig knew all three Frenchmen well and guessed at the civil war raking their team. Gambling on that, he attacked 300 metres from the finish.

Poulidor looked at Anquetil and Anquetil looked at Poulidor. And neither man moved. Poulidor wasn't prepared to chase Altig and be outsprinted by Anquetil and Anquetil, who never had much interest in single-day races anyway, would rather a German won the gold medal than see Poulidor, another Frenchman, get it. No matter that Anquetil had a decent sprint, especially for a time-trial specialist: he just wasn't going to take the risk of being beaten by his own team-mate. So, why?

Maybe the answer lies in what in those days happened after each Tour de France. We are still a long way from bike riders, even stars, getting salaries high enough that they can concentrate on just the few races that interest them. Many domestiques had no salary at all. So, to win your money each year, you raced. You raced for prizes and you raced for appearance money.

The greatest appearance money from the round-the-church-tower races that filled Europe went to the winner of the Tour. The trouble was that although Anquetil won the Tour five times, he rarely got paid any more than Poulidor, who never won it at all. Anquetil lacked charisma in public and he made the Tour as unexciting as possible so he could win it with no more effort than necessary. Poulidor, on the other hand, had the air of the slow-talking country boy that he was, a man who'd never even been on a train until he was called up as a soldier.

In the peloton, Poulidor was considered a moaner, as selfish and as a man to tell his grievances to the press rather than resolve them privately. It was Anquetil that the riders respected. But things were the other way round in criteriums and even if Anquetil and Poulidor asked the same sum to start (a fact which already irritated Anquetil), promoters were prone to slip Poulidor a little extra under the table.

The two men got the same start money, or close to it, because they had different agents. Anquetil used Daniel Dousset, a short, dark man of slightly gangster appearance who operated from a room of his sister's bar in Paris. Poulidor used Dousset's exact opposite, the quieter, more gentlemanly, better-dressed and fair-haired Roger Piel. Both agents were former riders and between them they had all French and much of European racing sewn up. The pair, but especially Dousset, were like gangsters defending their turf. Each yearned for dominance and fought for it as he could, to the extent that Dousset was prepared to wreck the careers of riders who crossed him by simply negotiating no more contracts for him. If that rider then transferred to Piel, it wasn't out of the question that the whole Dousset stable would ride against him - or even refuse to ride at all.

When you see that Federico Bahamontes of Spain won the Tour in 1959, that Henry Anglade came second and Anquetil third, you have to read it in the light of the Dousset-Piel war. Anquetil had no interest in having his criterium contracts bettered by Anglade who, as well as being disliked by many riders, also rode for Piel. Remedy: let the outsider Bahamontes win. Bahamontes couldn't even go round corners or downhill properly so he was hardly going to count in the criterium wars.

Back, then, to the world's of 1966. Anquetil (Dousset) is away with Poulidor (Piel). Altig (Dousset) has been dropped, but he is towed back up by Aimar (Dousset). Altig and Anquetil don't ride for the same trade team but Aimar and Anquetil were numbers 1 and 2 in the Ford team in that year's Tour, which Aimar had won. Two good reasons that Aimar had won were that Anquetil had dropped out and that half the rest of the field were happy to see his team-mate rather than Poulidor win. The previous year, they had ridden even more blatantly against Poulidor to let Anquetil win the Dauphiné Libéré and, more specifically, to stop Poulidor. Remember that Poulidor was popular with the crowd but not with the bunch.

Who knows if Aimar planned to tow Altig along with him? It's hard to think that he didn't at least know that it was happening. But did he care? Did he guess that Altig would outrace everyone or was did he think three Frenchmen in the break would outgun a single German? If he did, he was wrong.

Maybe somewhere in the shadows stood the Corsican figure of Daniel Dousset. We are, Altig once said, not sportsmen: we are professionals. And for professionals, money counts above all.