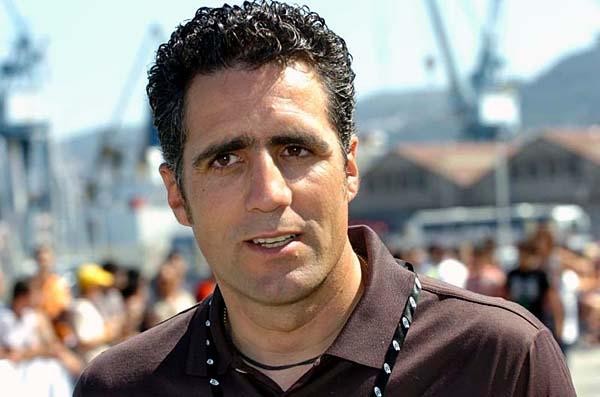

Olympic Moments: Indurain's last hurrah in Atlanta 1996

70 days to go until the London 2012 Games

With just 70 days until the start of the London 2012 Olympic Games, Cyclingnews continues its recap of some of the greatest moments in Olympic cycling history by taking you back to Miguel Indurain's win in the Atlanta time trial in 1996.

Indurain shares impressions in Australia

Indurain sees globalisation as major change in cycling

Indurain: I would have struggled on 2012 Vuelta a Espana route

Olympic Moments: 1992 - Boardman wins in Barcelona

Olympic Moments: 1948 - Godwin realises his dream

Olympic Moments: 2008 - Team GB rewrites the record books

Olympic Moments: 1984 - Grewal edges Bauer in thriller

No clear Tour de France favourite according to Indurain

Olympic Moments: 2000 - Nothstein, the last great American sprinter

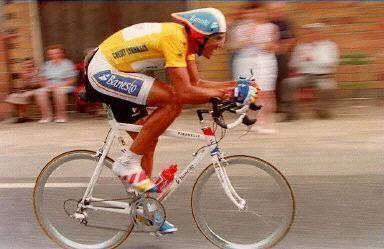

El Rey dominated stage racing in the early to mid-90s and he set records galore during his career. He was the only rider to win back-to-back Giro-Tour doubles, the first man to win five straight Tours, and the first winner of the Olympic time trial when the event made its debut at the Atlanta Games.

But two weeks before his win in Atlanta, the immovable rock had been moved, tossed, thrown like a pebble on a beach, when Bjarne Riis crushed the Spaniard with a series of impressive rides at the Tour de France. For the first time since 1990 (although you could perhaps count the 1994 Giro) Indurain had taken a kicking, finishing 11th in a race he had previously won with metronomic ease.

“He’d been on a downer since the beginning of that year’s Tour,” said writer William Fotheringham, who covered both the Tour and Atlanta Games that year.

“It meant that the Olympics had this rather intriguing aspect to it. We didn’t know if Indurain was finished or if he’d bounce back. We all knew he was an incredible rider against the clock but with Indurain you never really knew what he was thinking.”

Indurain’s Tour time trials had yielded mixed results. On a gloomy night in Holland at the start of the race he’d lost valuable seconds to his rivals in the prologue. As he slumped against his Banesto team bus perhaps he already knew that he remaining weeks would see him slip from his Tour throne. At Val-d’Isere he could only manage 5th, but on the penultimate stage he reminded everyone of his class by taking second. A baby-faced Jan Ullrich won the stage.

With Paris behind them the contending chrono gladiators set forth on their campaign to America. Indurain, Riis, and Boardman were among the headliners but there was a deep supporting cast. Evegini Berzin, winner of the Val-d’Isere time trial made the transatlantic crossing, so too world road champion Abraham Olano. Laurent Jalabert and Alex Zülle from ONCE were present, while a precocious Lance Armstrong, and stalwart Maurizio Fondriest added youth and experience. The first ever Olympic time trial for professionals promised to be a battle royal.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The 52.2km long Buckhead cycling course comprised of four laps. The roads were wide, but the main obstacles came through the conditions. Setting off in waves which had been decided by seedings, the early pace setters had to contend with heavy rain which left the course drenched and water levels high.

“It was hot humid, with huge rain storms. I think we had nearly 100 per cent humidity,” says Boardman, who started in the final and fourth wave of riders, which included Indurain and compatriot Olano.

“I just couldn’t deal with the heat,” Boardman says, but he still romped to an early lead on the first lap. The British rider had endured a horrendous time in the mountains of the Tour and had been unceremoniously dropped on every mountain stage, struggling home to 39th in Paris. Still, the time trial was Boardman’s domain and as he set out on the course he only had gold on his mind.

He was fastest at the first time check, while up ahead Lance Armstrong, out of the saddle and looking ill at ease on a time trial bike, was cheered on by the home crowds.

By this point most of the competitors had finished. Maurizio Fondriest, who hadn’t ridden the Tour, led with a time of 1:05:01. A medal looked likely but with Indurain warming up, and Abraham Olano about to take the start ramp, the Italian was left to wait nervously at the finish.

Berzin was the next rider to start. The diminutive Russian, dubbed Mozart on pedals, had the frustrating ability to be mesmerising one day, but woeful the next. Which Berzin turned up in Atlanta was anyone’s guess.

The reliable Uwe Peschel, who finished third behind Indurain and Olano in the worlds time trial the year before, was the next. A winner of the team time trial in 1992, he powered down the ramp just as Olano, his florescent Briko glasses peaking out above his nose, settled onto his Colnago and inched towards the time keeper.

Boardman continued to eat up the road, his sleek position on the bike giving him the aerodynamic position his rivals craved. However there was a problem. The heat and the humidity were taking their toll. The helmet was quickly thrown to the ground, and his water bottle soon followed. His shoulders, which were always motionless, began to rock.

Olano started and Indurain, the last man, took his position on the start ramp. Whereas Zülle had looked twitchy and Berzin petrified, the Spaniard appeared colossal. He was a rock once more.

After the first lap Boardman was 17 seconds up on the Spaniard but a lap later the advance had been cut to just 3 seconds. On the long sweeping descent towards the start of the third lap, the British star crouched further over the bars, tucking as low as possible to save every second he could. Minutes later Berzin swept through the same corners, cautious, and off the pace. Like Boardman, he too was suffering in the heat and had discarded his helmet.

At the halfway point Indurain was ahead, his tall physique churning through the gears as those of in front continued to wilt under the pressure. By the time Indurain started his third lap his advance had pushed out to 13 seconds.

Olano, sensing blood, forged ahead as well, cutting through Boardman and securing second.

Indurain crossed the line in a time of 1:04:05, 12 seconds ahead of Olano, with Boardman having to settle for 3rd. Riis limped home in 14th, Berzin 15th, and Zülle 7th.

Indurain punched the air in a rare show of emotion but asked if he would trade his gold medal for a Tour de France victory, Indurain did not hesitate to say yes .“For any professional cyclist, winning the Tour is the pinnacle of their career, whereas winning the Olympic title is purely symbolic," he told reporters.

It marked Indurain’s last hurrah and his last win as a professional. His relationship with Banesto had began to turn sour at the tail end of 1995. During the Worlds in Colombia Indurain had put together plans to secure victory in the time trial, road race and then a bid to regain the hour record. He only won the time trial and allegedly slammed his hotel door in his bosses' face after learning that they’d blocked telephone calls from his wife.

Failure at the Tour followed, but the final nail in the coffin came in the shape of the PR disaster when Banesto twisted his arm into riding the Vuelta in September. He quit on stage 13, and although a number of teams enquired about his services for 1997, he retired on January 2, 1997, at the age of 32.

Almost 17 years and 3 Olympic Games later it’s hard to put Indurain’s Olympic ride into context. After the defeat at the Tour his gold medal only partially made up for July’s Tour loss. But that’s understandable. Unlike now, where professional riders lust after Olympic medals, in the mid-90s the Tour was the pinnacle, and the Games, which had until then been open to amateurs, was seen as just another race on the calendar. Fotheringham describes the 1996 Games as ‘somewhat experimental’ for the riders.

And while an Olympic medal offers fame and status as a national hero Indurain had reached that point well before the Games. Spain voted him the greatest athlete of the 20th century and when he retired El Pais wrote “look through the list of Spanish heroes and heroines and you will find nobody like Miguel.”

Never brash, never arrogant, the Spaniard always appeared humble and polite. Cycle Sport recounted that during his long career he lost his temper just three times, and one of those episodes came after Jesper Skibby ran over his foot.

On the day he retired Marca’s front page displayed a huge tear but while they mourned the loss at least they had his final hurrah in Atlanta.

“I thought the Olympics would be the perfect way to bow out,” the great man said at his final press conference. They should have been.

Daniel Benson was the Editor in Chief at Cyclingnews.com between 2008 and 2022. Based in the UK, he joined the Cyclingnews team in 2008 as the site's first UK-based Managing Editor. In that time, he reported on over a dozen editions of the Tour de France, several World Championships, the Tour Down Under, Spring Classics, and the London 2012 Olympic Games. With the help of the excellent editorial team, he ran the coverage on Cyclingnews and has interviewed leading figures in the sport including UCI Presidents and Tour de France winners.