Olympic Moments: 2008 - Team GB rewrites the record books

80 days to go until the London 2012 Games

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With just 80 days until the start of the London 2012 Olympic Games, Cyclingnews continues its recap of some of the greatest moments in Olympic cycling history by taking you back to the Beijing Olympics of 2008.

Brailsford: "We'll win fewer than eight golds"

Cavendish wins BBC Sports Personality of the Year award 2011

Brailsford nurtures shoots of growth as Great Britain march towards London Olympics

Wiggins bridges 45-year gap at Paris-Nice

Pendleton wins sixth world sprint title after rollercoaster semi with Meares

Dominance in sport is measured mainly in two ways: firstly, by complete and consistent superiority over the opposition during a specified time period; and secondly by the smashing of records and the rewriting of the history books.

For a two-week period at the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, Great Britain's cycling team swept all before them. Individual and cumulative records tumbled and stars were born. And, when it was all finished, fans, journalists and ex-pros were left scratching their heads in wonder at how such a rapid and comprehensive transformation in a nation’s cycling fortunes was achieved and doubting that they would ever see the like again. This is the story of how it all unfolded.

Preparing for success

The seeds of Great Britain’s unprecedented achievements in Beijing, where the team won eight gold medals and 14 in total (both records) can be traced back to the period between the Sydney Olympics of 2000 and the Athens Games of 2004. In Australia, Jason Queally raced to gold in the 1km time trial and Great Britain supplemented his success with one silver and two bronze medals.

Part of the Team GB squad for Sydney were two men who would go on to become lynchpins of the drive for even more glory at Athens and then Beijing. Chris Hoy and Bradley Wiggins, 24 and 20 years old, respectively, and silver and bronze medal winners respectively, cut their competitive teeth on the Olympic stage, showcasing both their talent and potential.

In the years between Sydney and Athens both men would win world championship gold medals and enjoy success at Commonwealth level. But it was the appointment of David Brailsford as performance director, in succession to Peter Keen, in the run-up to Athens that provided added impetus. Brailsford immediately set about revolutionising professional cycling in Britain and started assembling the best coaching staff in the world to give the likes of Wiggins, Hoy, Queally and the rest the best opportunity to improve.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The results in Athens only showed marginal improvement. Hoy and Wiggins each took individual gold medals but the overall medal haul showed progress only in colour and not in numbers. Team GB again boarded the plane home with four cycling medals – two golds, one silver and one bronze. Brailsford declared himself satisfied with the team’s performances but in the background work was already underway to move the squad of riders up to the next level.

Brailsford’s team evolved further and they identified regular use of the Manchester Velodrome as a key tool in its bid to overtake their rivals. The Team GB backroom staff by now included Shane Sutton and Rod Ellingworth, who were universally recognised as two of the best coaches in the world, and 1992 Olympic gold medallist and multiple world champion Chris Boardman, who acted as a consultant. In Athens Australia had won a record six golds and four years earlier Germany had won 10 cycling medals overall, and these two nations set the benchmark as Team GB worked tirelessly to bridge the gap in the four years between Athens and Beijing. Attention-to-detail was the buzz phrase. Nothing was left to chance and months of persistent lobbying led to an increase in funding for the sport.

During this time, more young talent emerged to aid the likes of Hoy, Wiggins and Queally. The likes of Mark Cavendish and Geraint Thomas produced eye-catching performances on the track at world and Commonwealth level in the inter-Olympic years, while a 20-year-old Jason Kenny was in the process of forcing himself into contention for selection for Beijing.

In the women’s sphere, the talented but disillusioned road racer Nicole Cooke had been brought into the fold via Brailsford’s careful man management and Victoria Pendleton had matched the exploits of Cavendish and Thomas to raise her profile to that of team talisman. Another woman showing remarkable progress was Rebecca Romero, who had made the decision to move from rowing (where she had won Olympic silver for Great Britain in 2004) to cycling and was tearing up the track in the months leading up to the departure for Beijing.

So as Brailsford and his team boarded the plane for the long flight to Beijing, confidence was high. Almost five months earlier, at the UCI Track World Championships in Manchester, Britain had won nine golds and smashed several world records in the velodrome that had been so crucial to their progress, so the prospect of improving on results from Athens was the least that the team and an increasingly engaged British public were expecting. But the record-breaking run that followed exceeded all expectations and would have far-reaching consequences for the sport of cycling in Great Britain.

Record breakers

Team GB’s first success, almost ironically given the headlines of the previous few months, came not in the velodrome but on the road. Cooke powered to victory in the women’s road race in dreadful conditions to get the entire British Olympic squad off to a flying start with its first gold. Cooke had finished fifth in Athens and in the aftermath had been vocal of her disillusionment with the structure of British Cycling. Her success was testament to her talent, the sweeping structural changes put in place and the management skills of Brailsford and his team.

Cooke had lit the blue touch paper. Five days later Hoy, Kenny and Jamie Staff avenged a world championship defeat five months earlier by beating France in the final of the team sprint to open Britain’s account on the track.

"To win as part of a team is a totally different feeling from the 1km time trial in Athens," told BBC Sport after clinching gold, offering an insight into the closeness of the squad. "Our friendship has been so dominant in the last few years. As part of a team, you can't let anyone down. There's still plenty in the tank. At the end of the week, if I get three [gold medals], I'll do a dance for you and that's a promise."

Hoy’s promise proved to be a rash one. The following day he added gold in the men’s keirin, and his hat-trick was completed three days later when, in the last track event of the Games, he defeated his teammate Kenny in the final of the individual sprint. In the process he became the first British athlete in a century to win three individual gold medals at an Olympic Games.

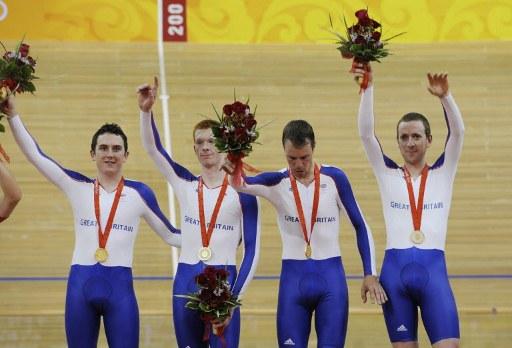

Astonishingly, there were four more golds in between. Wiggins and Romero secured the double for Great Britain in the individual pursuit events and Pendleton defeated Australia’s Anna Meares to win the women’s individual sprint, which marked the beginning of an enduring rivalry between the pair that is set to play out its possibly final defining chapter in London this summer. And 24 hours before Hoy won that final gold, the men’s team pursuit was transformed into a procession, with Wiggins, Thomas, Ed Clancy and Paul Manning thrashing Denmark by almost seven seconds in the gold medal race and smashing the world record.

“They are super-perfectionists,” one of the Danes was heard saying after they had been humbled in spectacular fashion. “Their equipment is always the best and they have the best coaches for everything.”

What happened next?

For Brailsford, those words were vindication of his methods, and music to his ears. His stock – not just in British cycling, but in British sport in general – rose exponentially in the months following the Games. After receiving offers to move into other sports and industries, he committed himself to cycling on two fronts – by extending his contract with British Cycling beyond the London 2012 Olympics and by allying himself to a brand new project as head of a brand new British-based road racing team with designs on Tour de France success. In 2009, Team Sky was born.

That fledgling team’s totemic figure is Wiggins, who decided to switch his focus from track to road after Beijing. In 2009 he equalled the best British performance in the Tour de France by finishing fourth overall, and after a couple of troubled seasons he has shown dramatic improvement in the last 12 months with victories at the Criterium du Dauphine, Paris-Nice and the Tour de Romandie. As a result he is now one of the big favourites for this year’s Tour. He was joined in Team Sky colours in 2010 by Geraint Thomas, who continues to switch between track and road and is aiming for further gold in London this summer.

Pendleton and Kenny have both enjoyed major success on the track since Beijing and are fancied to add to their tally of gold medals in London. All of the gold medallists were bestowed with honours from The Queen following their victories in 2008, most notably Hoy. He was knighted for his achievements and subsequently enjoyed two other huge honours – the BBC’s prestigious Sports Personality of the Year Award in 2008 and the naming of the Glasgow Velodrome, in his native Scotland, in his honour. At 36, he is hoping for a glorious swansong this summer.

As far as footnotes go, the forgotten man of Beijing mustn’t be discounted. Cavendish was the only member of the British squad not to win a medal. Yet he has put it behind him to become the most feared road sprinter on the planet. The 26-year-old from the Isle of Man is the current road world champion and the holder of the Tour de France green jersey, and his exploits in winning both enabled him to emulate Hoy by winning the BBC award in 2011 – becoming only the third cyclist to do so. Cavendish, who signed up to join Wiggins, Thomas and Brailsford at Team Sky in the 2011 off-season, can see his final redemption approaching fast. Gold in the 2012 Olympic road race in front of his home fans, an event for which is the overwhelming favourite, would finally lay his Beijing ghosts to rest.

Mark joined the Cyclingnews team in October 2011 and has a strong background in journalism across numerous sports. His interest in cycling dates back to Greg LeMond's victories in the 1989 and 1990 Tours, and he has a self-confessed obsession with the career and life of Fausto Coppi.