Olympic Moments: 1984 - Grewal edges Bauer in thriller

Our countdown to London 2012 Games continues

With just 60 days until the start of the London 2012 Olympic Games, Cyclingnews continues its recap of some of the greatest moments in Olympic cycling history by taking you back to the Los Angeles Olympics of 1984.

Background: Cold War tensions

The long and politically-charged build up to the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles started way back in January 1980, when US President Jimmy Carter issued an ultimatum to the Soviet Union. With Cold War tensions at their highest for more than a decade, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979. This act of aggression was condemned by the United Nations and the West, and Carter declared that if Soviet troops did not withdraw within one month, America would boycott the 1980 Summer Olympics, which were to be hosted in Moscow.

Carter's one-month deadline passed and his promise of a boycott stood, with America and many of its key allies opting out. Four years later, in retaliation to the US boycott and in protest against the explicit anti-Communist agenda of the Reagan administration, the Soviet Union and its Eastern Bloc allies responded by boycotting the Los Angeles Games. For two consecutive renewals, the summer Olympics had been used as a tool by politicians.

In 1980, Eastern Bloc countries had dominated the medal table in unprecedented fashion, with competition weakened by the absence of the West. The exact reverse would occur in 1984, with the USA capitalising on the absence of its main ideological and sporting rival by winning a record 83 gold medals. Somewhere on that artificially-inflated list is the name of Alexi Grewal, who became the first American to win gold in the Olympic road race. Like all other medallists in 1980 and 1984, there is always the boycott footnoted to his success. But it wasn't without plenty of drama both in the lead up to the event and in the way the race and the aftermath played out.

Suspension and appeal

Unsurprisingly, the top six in the 1980 Olympic road race were all from Eastern Bloc countries and none of them would be making the journey to Los Angeles to compete over the 12-lap, 190km course along the Pacific coast. In 1984 rules were still in place that banned professional cyclists from competing at the Olympic Games and that, combined with the boycott, had pundits scratching their heads as to who would be the favourite to take gold.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The challenge from the home team centred around two Colorado natives - Grewal and Davis Phinney. In the run-up to the Games it was Phinney who was the more fancied of the two riders, despite the relatively undulating course that a few detractors said might not suit his skills. Phinney was best known as a sprinter first and foremost, and as a time trialist second. Many observers believed that the course was set up more to Grewal's strengths as a climber but their main misgivings centred around his state of mind heading into the Games.

Just 10 days before the race, Grewal tested positive for the stimulant phenylethylamine at the Coors Classic, which was won by his US teammate Doug Shapiro. The US Cycling Federation immediately imposed a 30-day ban on Grewal, which meant that he was to miss the Games. Desperate to compete in a home Olympics on a course that favoured him - a once-in-a-career opportunity - Grewal staked everything on an appeal. His argument centred on his asthma, a condition for which he legally took the drug albuterol. His legal team successfully countered that it was impossible to differentiate between the two drugs and Grewal saw his ban overturned and arrived at the start line exonerated.

High drama and history in California

What kind of a frame of mind Grewal was in at that start line was anyone's guess, the media said. The events of the previous few days were certain to have affected him in some way. Would they lead to Grewal under-performing? Or would the last-minute reprieve inspire him to channel his relief positively and use it in his favour? It was impossible to tell. In the eyes of the home fans the smart money was on the consistent and metronomic Phinney rather than his unpredictable, maverick rival. Also in the picture was Canadian rider Steve Bauer, who had won three consecutive national road race championships between 1981 and 1983.

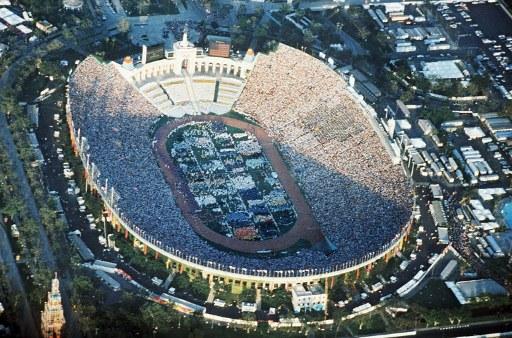

300,000 spectators lined the roads, desperate to see an American victory in the road race for the first time. Nationalist fervour was reaching fever pitch, even by American standards, with sport seen as a vehicle to promote political supremacy and prosperity. At 1:00 pm local time, under a blazing Californian sun, 135 riders from 43 countries set out from the start in Los Angeles in conservative fashion, with the finish in Mission Viejo 45km south east of the city some 190km and five hours away.

Several kilometres in, the riders started the first of their 12 laps that would ultimately lead to the finish. With three laps and under 30 miles to go, a leading group of seven had pulled clear of the main peloton: Grewal, Phinney, Bauer, Thurlow Rogers (USA), Rogelio Arango (Col) and the Norwegian duo of Morten Saether and Dag Otto Lauritzen.

With under two laps to go Grewal attacked and the only man who could keep with him was Bauer. The pair built up a 30-second lead over the Norwegian duo and were set for a battle to the line. Phinney had no answer and his dreams of a medal were dashed.

With less than 10km to go Grewal appeared to be struggling. His uphill solo attack into a headwind looked to have taken its toll and Bauer was by this point looking comfortable in front, carrying the air of a man who had an extra gear up his sleeve should he need it.

The pair took turns leading and drafting respectively before a final, dramatic sprint to the line. Bauer made the first move and looked to have done enough. But his American rival - a year younger at 23 - sat patiently and swooped on Bauer's inside to secure an historic victory by the length of a wheel that a few days prior had looked impossible. Down the road, some 21 seconds back, was Lauritzen, who pipped his compatriot to the bronze medal. Phinney could only manage fifth, almost a further minute in arrears.

What happened next?

After the most emotional and draining of victories, Grewal turned professional in the aftermath of the race. His professional career never lived up to the promise of his win in Los Angeles and was not without controversy. He struggled to forge a career in Europe and a low point came at the 1986 Tour de France, when he was thrown off his 7-Eleven team for spitting at a cameraman. Injury and ineffective performance plagued him for the following few years and he announced his retirement from cycling in 1993. In 2008, he admitted to doping throughout his amateur and professional career and claimed that it was widespread throughout the peloton.

Phinney also turned professional after the race and his career was much more decorated. He put the disappointment of finishing out of the medals behind him, winning stages at the Tour de France in 1986 and 1987 and coming second in the points classification the following year. He was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease in 1999 and is the father of current BMC rider Taylor Phinney.

Bauer finished tenth overall at the 1985 Tour de France. Three years later he went even better and finished fourth overall. He spent time in the yellow jersey that year and also in 1990.

But the most successful professional career forged by a rider who took part in the 1984 Olympic road race was that of Miguel Indurain. At the tender age of 20, the Spaniard failed to complete the race in Los Angeles, but would go on to win Olympic gold 12 years later and become the first man to win the Tour de France five consecutive times between 1991 and 1995.

Mark joined the Cyclingnews team in October 2011 and has a strong background in journalism across numerous sports. His interest in cycling dates back to Greg LeMond's victories in the 1989 and 1990 Tours, and he has a self-confessed obsession with the career and life of Fausto Coppi.