No more second chances as Tour de France hits the Alps – Preview

First place and sixth place on GC separated by just over two minutes

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In recent years, when there have been just four days of racing left to go at the Tour de France, there's been excessive certainty about who will be handed a microphone for the victory speech in Paris on the final Sunday. But this year, just the opposite is true.

Brailsford: There are two races in this year’s Tour de France

Alaphilippe defiant and ready for Tour de France yellow jersey defence

Luke Rowe and Tony Martin expelled from Tour de France

Team Ineos looking to appeal against Luke Rowe's expulsion from Tour de France

Rowe and Tony Martin apologise for Tour de France incident in joint statement - Video

As things stand, Julian Alaphilippe (Deceuninck-QuickStep) has the upper hand, time-wise, with a 95-second 'cushion' between him and second-placed Geraint Thomas (Team Ineos). And there are plenty of prior Tours that have been won or lost by less, with the 1989 Tour – currently being cited with increasing regularity as the only modern-day Tour comparable in terms of last-minute tension – being a case in point.

But quite apart from Alaphilippe's inexperience as a Grand Tour contender, and the doubts over whether he can remain in contention in the approaching high mountains, there's also no lack of rivals within shouting distance of yellow who are itching to oust him from the top spot overall.

Aside from Alaphilippe's advantage, a further 39 seconds are all that divide Thomas from the other four main GC rivals: Steven Kruijswijk (Jumbo-Visma), Thibaut Pinot (Groupama-FDJ), Egan Bernal (Team Ineos) and Emanuel Buchmann (Bora-Hansgrohe). Rarely have the words 'everything to play for' been so applicable to so many different riders so late in the game.

The Tour has three stages in the Alps to resolve this particular conundrum of who wears yellow in Paris. But will it have to wait until the final stage? As the only full-length day in the mountains, stage 18's 208 kilometres across two Hors-Catégorie ascents of the calibre and renown of the Col d'Izoard and the Col du Galibier is undoubtedly the hardest on paper – and it could decide the race.

The Galibier is officially 23 kilometres long at 5.1 per cent, combining with the much gentler ascent of the Col du Lautaret to the point where the race veers right and onto the climb proper. Double Tour de France winner Bernard Thévenet, who lives in nearby Grenoble, recognises that the southern ascent of the monster Alpine climb is not the harder of the two. But as Thévenet also points out, there's more than enough climbing terrain to do real damage.

The Tour de France peloton climbs the Izoard (Bettini Photo)

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"The first part up the Lautaret is really gentle, so it's just the last seven or eight kilometres of the Galibier where we'll see big differences emerge," Thévenet tells Cyclingnews. "And this year, as well, the race descends down the opposite side of the Galibier to the finish in Valloire.

"But if you're a rider at three or four minutes in the overall right now, you could attack on the Izoard like Andy Schleck did in 2011 and really do some damage. That's particularly true if you've got teammates waiting in the valley from an earlier break who can haul you up the Lautaret, like Schleck had, too."

However, as Thévenet says, the rider in yellow at Valloire being the same rider in yellow in Paris "is just one of four or five scenarios I can see playing out".

"Things could be decided much later in the Alps as well, as Thibaut Pinot has predicted," he says.

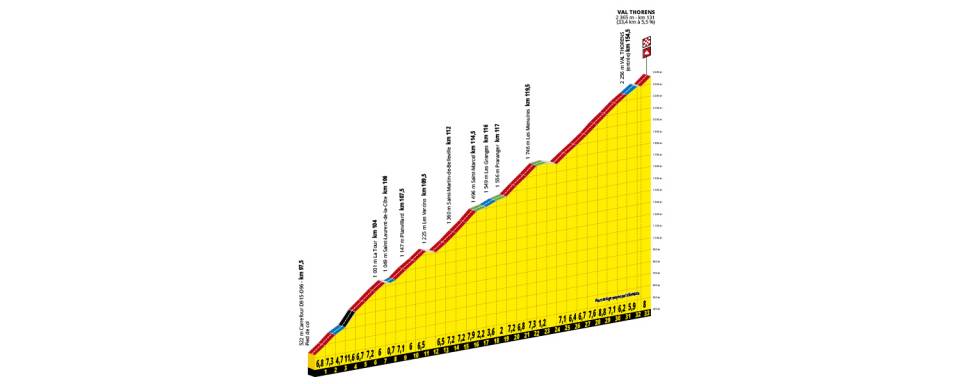

Speaking on Monday, Pinot insisted the overall will not become clear before the final Hors-Catégorie ascent of the race: the agonisingly long, if shallow, drag up to Val Thorens on Saturday. But Friday's short, punchy stage over the Col de l'Iseran and then a quicker ascent to Tignes could also prove to be a turning point.

Essentially, with no team in full control of the Tour, and no one rider clearly dominating, there are too many possible plot lines to risk making full-scale predictions.

"The race could, easily, be on a knife-edge all the way to Val Thorens," says Thévenet. "Maybe it'll be decided before then, but certainly that could happen, too. Right now, you just can't tell."

Part of the problem – and the intrigue of this year's race – is how similar in strength each rider seems to be, and how uneven their form is, too.

"One day, one guy looks stronger then another does, and even in the same stage, these same contenders give you another impression," says Thévenet. "For the last week, we all thought Alaphilippe would lose the jersey before Nîmes, and in fact he's still got a good gap."

Thévenet, let it be said, is enjoying this particular battle immensely.

"This is my 47th Tour, and I don't think I've seen such a hard-fought Tour from the first day in my life. It's out of the ordinary – hors norme," he tells Cyclingnews.

Nor is it just the GC battle that is making this such a hard race to predict. As Thévenet points out, the lack of transition stages and large numbers of teams and riders in need of clinching some kind of success means plenty of the Tour's secondary actors are still desperate to make an impact.

"Back in my days as a racer, it's true that there would be a slower start to stages. But another key difference between now and then is that in those days if you weren't feeling good, you'd give it everything you could to finish in the main peloton even so, because getting dropped was really bad for your reputation. It was viewed as a real disgrace.

"Nowadays, people get dropped or even ease back themselves on stages where they're not going to fight and nobody really cares anymore," he continues. "They live to fight another day. So as a result of this different attitude to my era, you've got 130 riders who are way off the GC, and although they've had one or two bad days, they're still strong because they haven't tried so hard to stay in the bunch, so they can attack and affect the race."

Bernal, Alaphilippe and Thomas on the Tourmalet (Bettini Photo)

Further fanning the flames of a high-powered trek through the Alps for the Tour this year is the fact that only a very small proportion of teams have won this year.

"There are lots of teams who have nothing," says Thévenet. "And they have to go for it. So that's why you're getting such big breaks as well – like that day when we had 42 off the front, and another with 36. It's very unusual."

Rather than breakaway racers or attitudes to getting dropped, the bedrock to this exceptional Tour finale, though, is that the riders are going into the Alps with everything to play for on the GC. Beyond the Alps, there are no reasons to hold back, no second opportunities, one last-chance saloon. With so many players around the yellow jersey table, it's very hard to see how the cards will fall.

"Last year, four days before the final stage, you could be 85 per cent sure who was going to win," Thévenet concludes. "Either Geraint Thomas or Chris Froome, in theory, but you could be pretty sure it was Thomas. This time, we've got no idea."

The balance of power is so delicate that if the slightest error is made by anybody, they're out of the fight, says Thévenet.

"And if the best-known names watch each other too closely, someone like Buchmann could easily shoot off the front and get ahead," he said of the Bora-Hansgrohe rider who is currently sixth overall.

"That's what's so extraordinary at this Tour: we've been fighting flat out for nearly three weeks and we've still got five riders who can win. Normally, when there's a fight like that, there are two or three still up there with a chance of winning, at most. This time, it's not like that at all – which, for the spectators, is great."

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.