'No further information available': ONCE, McEwen and the 1995 Mount Buller Cup

Remembering the first race covered by Cyclingnews and its impact on Australian cycling

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The first race report ever to feature on Cyclingnews was nothing if not concise. The event was the Mount Buller Cup in Victoria, the winner was Neil Stephens, and, in February 1995, that was as much as any of the website’s earliest readers were going to find out about it via their dial-up internet connections.

Mount Buller Five Day Tour of Victoria

Australia, February 1995

Final G.C.

1. Neil Stephens (Australia)

No further information available.

A quarter of a century on, there is only marginally more detail to be unearthed amid the recesses of the worldwide web. A scan of an online archive of Australian newspapers reveals some perfunctory reports in the Canberra Times about a Canberran’s overall victory. In Stephens’ adopted Spain, a sidebar in a digitised edition of Mundo Deportivo mentions the ONCE man’s success in what it calls the ‘Vuelta Summers de Australia.’

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Cycling Archives, as is so often the case for races from the pre and early internet eras, offers more firm details than anyone else, providing dates (January 28-February 1), a list of stages (six), and the top three finishers in each. It’s a precious resource, but the results sheet only provides the final word; it doesn’t tell the full story. Bike races, or at least their memories, live in the spaces between the rows and columns of names and times.

Rupert Guinness, the dean of Australian cycling journalists, has been filling in those gaps since the 1980s, and he is the obvious first port of call when seeking the further information that was unavailable a quarter of a century ago. Currently at home in Sydney and in training for the Virtual Race Across America, Rupert responds to say that he wasn’t on hand at Mount Buller, which briefly begs an existential question: If a pro bike race was held in Australia, and Rupert Guinness wasn’t there to report on it, then did it take place at all?

Fortunately, Rupert is immediately able to point us in the direction of someone who can help, and the philosophical conundrum is swiftly resolved: Yes, but only if John Trevorrow organised it.

The journalist Robert Caro has used his multi-volume biography of Lyndon Johnson as a prism through which to refract the history of 20th century America. To start recounting the history of Australian cycling, one could do worse than compile a biography of John Trevorrow.

Whenever the Sun Tour came to Gippsland in the 1950s, riders were put up at the Trevorrow house in Morwell and the young John was quickly inspired. Aged 20, he took bronze in the 1970 Commonwealth Games. Two years later, he competed at the Munich Olympics where fellow countryman Clyde Sefton claimed silver.

A professional career followed, though in that era, an Australian rider was not compelled to travel to the northern hemisphere to pursue it. The strong local scene provided rewards not altogether removed from those available at that time in Europe, all while allowing riders to work and build their lives at home.

Before Phil Anderson’s stint in the maillot jaune in 1981 changed everything, Australian professionals tended to flit between hemispheres rather than settle in Europe. Trevorrow’s talent carried him to three overall victories at the Sun Tour and three Australian pro titles, as well as a series of fine but frequently unfortunate cameos in Europe – including a Giro d’Italia appearance in 1981 – that earned him the affectionate nickname of ‘Iffy’. If only.

On hanging up his wheels, Trevorrow wrote about cycling for the Herald – and later, for Cyclingnews – and moved into race organisation. His first major promotion came in January 1989 with the inaugural Bay Classic, held in the suburbs of Melbourne. “The idea was to bring the racing to where the crowds were,” Trevorrow tells Cyclingnews.

The Bay Classic took place in January, at the height of the Antipodean summer, and this, too, was a novelty. In Australia, road racing took place in winter and track racing in summer, meaning that the road season concluded in October, just as it did in Europe. “I got a lot of pushback from some officials and people in higher places who said I was going to ruin track racing, but I said that’s stupid,” Trevorrow says.

The alignment of the Australian and European seasons meant that Phil Anderson didn’t race on home roads for the first 14 years of his professional career, a sequence only broken in January 1994, when Trevorrow persuaded him to line out at the Bay Classic ahead of his final season in Europe.

The success of Anderson’s belated homecoming made a case for more January road racing, and Trevorrow duly expanded his portfolio in 1995. To the Bay Crits, he added the Melbourne Classic one-day race – which doubled as Australia’s pro road race championship – and the inaugural Mount Buller Cup. Together, they were billed as the ‘Summer of Cycling,’ which helped to sell the idea to sponsors, including Jayco, owned by a businessman called Gerry Ryan who had entered cycling sponsorship by backing Kathy Watt in 1991.

Everything was in place, bar one vital detail. With Anderson now retired, another recognisable name from the European peloton was required. Trevorrow knew just who to ask.

Australian riders of Neil Stephens’ generation felt obliged to burn their boats if they were to succeed on the Old Continent, and for most of his career, he had fought against the very idea of going home. It was almost synonymous with defeat.

“I remember pulling out of a race in England and sitting down beside a river and just crying because I didn’t want to get back on the plane and fly home because that was the end of the story,” Stephens, now a directeur sportif at UAE Team Emirates, tells Cyclingnews. “It cost you maybe $2,000 to get a plane ticket, so if you went home, it wasn’t a comma or a semi-colon; it was a full stop. And I bloody wasn’t going to do that.”

Stephens had come to England in 1984 on the invitation of Shane Sutton, though the promised contract took time to materialise. Indeed, Sutton didn’t even show at the airport, seemingly forgetting that he had invited his countryman to make the trip. “I had my suitcase in one hand and my bike in the other and he bloody wasn’t there, was he?” Stephens laughs. Undeterred, he made his way to Birmingham and rode out the season for the ANC team.

The death of Stephens’ father meant that he spent 1985 in Australia. He raced a little but spent the bulk of the year driving his late father’s truck. “I basically kept the business going while it was for sale,” he says. In 1986, John Trevorrow’s friendship with Gianni Savio got him a place on Santini and a ride in the Giro d’Italia, though it was a chastening experience. “I got a bit of a flogging and I thought, shit, I’m not that good,” Stephens says. “So I thought I’d hang it up.”

The trouble was, he didn’t know how. In 1987, Stephens was selected for the Villach World Championships and he prepared by racing again in England. That earned him a place on the Zero Boys team for 1988, a makeshift squad whose selling point was the blank space on its jersey, which – in theory – allowed it to solicit local co-sponsors everywhere it raced. “It was a great concept,” Stephens says, “but it didn’t work.”

It at least got him a ride in big races, and helped to secure a paying contract with Caja Rural the following season. Stephens settled in the Basque Country and carved out a reputation for himself in Spanish cycling over the next three years. He was on the point of moving to Amaya for 1992 when he felt emboldened enough to approach Manolo Saiz at the start of a race to offer his services to ONCE.

“I thought, fuck it, this is just the team I wanted to be in,” Stephens says. “I told Manolo I’d take half of what I was already on to be on his team. He wanted someone with passion, and he said he’d pay me what I was already on, and so, after years on little teams with no money, I got to ride the Vuelta, Giro and Tour in one year. If somebody had said to me at the end of 1992, ‘Listen, Neil, we haven’t got a spot for next year,’ I could have stopped cycling a happy man.”

By early 1995, Stephens was a mainstay of an ONCE team that, in the popular imagination at least, existed as the iconoclastic counterpoint to Miguel Indurain’s more orthodox Banesto outfit. It rode to blow races apart rather than hold them together. It was a Spanish team with foreign leaders in Laurent Jalabert and Alex Zülle. It had a manager, Saiz, who had never raced a bike but who pushed for every marginal technological innovation. “This team is different,” he once claimed, “because it has a soul.”

Saiz has been persona non grata in professional cycling since Liberty Seguros, the successor of ONCE, morphed into Astana in June 2006 following his arrest as part of the Operacion Puerto doping inquiry. Just last week, Saiz insisted that his teams had been “the cleanest in cycling.”

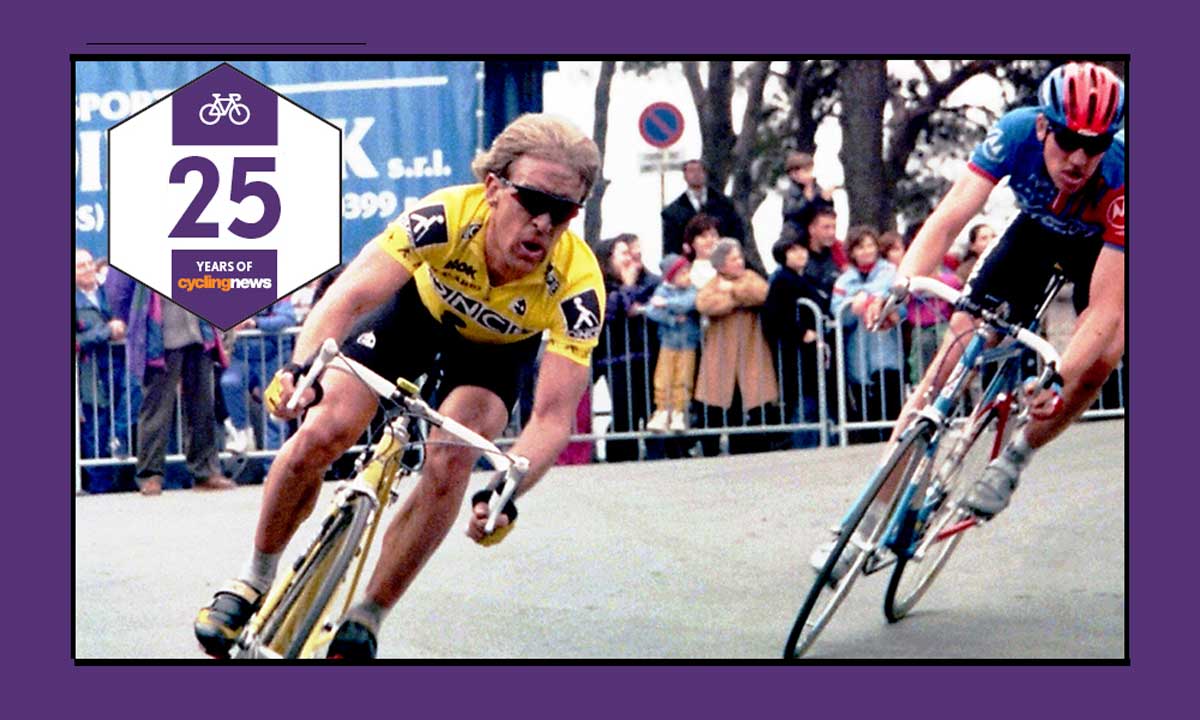

In 1995, before the watershed moment of the Festina Affair, such ethical considerations were perhaps moot for the cycling public. ONCE were known simply as the most glamorous team of the era. The distinctive yellow jerseys were a fixture at the head of the peloton, and Stephens had established himself as a most deluxe domestique. With Anderson retired, he was also now the most famous Australian rider, and the obvious choice to be the marquee name at Trevorrow’s Summer of Cycling.

Finding a way to toggle between Australia and Europe certainly appealed to Stephens. He had always intended to return to Australia when his career was over, but, now 31, he had begun laying down roots in Oiartzun, near San Sebastian. He married Amaia later in 1995, and, a quarter of a century on, a corner of Gipuzkoa remains forever Australia.

“I met my wife in ‘92 and in ‘94, we were nearly going to break up, because I said, ‘Look, I’m definitely going to go back to Australia, so we’ve got no future,’” Stephens says. A compromise was reached. “She agreed that if I couldn’t get work in Europe at the end of my career, she’d come to Australia. I look at that now and I reckon it wouldn’t have happened. And, of course, she says she never said that either…”

While the 1995 Mount Buller Cup helped to bring Stephens’ two worlds closer together, he was joined in the ONCE squad that year by a man who had already spent his whole life straddling two continents. Pat Jonker was born in Amsterdam but grew up Adelaide, and that duality continued in his cycling career. When he first went to race full-time in Europe in 1988, he sought to emulate Anderson and Allan Peiper by riding for a club in France (Aubervilliers rather than ACBB), but he later passed through the Australian Institute of Sport before turning professional.

“I was probably the last Australian to turn professional after racing with a club in Paris,” Jonker tells Cyclingnews from Adelaide. “Later, I rode one year with the Australian Institute of Sport with Heiko Salzwedel, but you could actually credit a lot to Shayne Bannan. I spent time with him in the late 1980s in Italy. He got money together so that the Australian team could ride together there. He was trying to give riders a structure to turn professional.”

Jonker was in his third season as a professional when he joined ONCE in 1995. His results the previous year, including 8th at the Dauphiné, had helped, but a reference from Stephens carried at least as much weight with Saiz. “If it wasn’t for Neil, those results wouldn’t have been enough,” Jonker says. “Everybody wanted to ride for ONCE. We were ultra-professional, we had the best equipment… I think you could say we were the Team Sky of the 1990s.”

Major riders and teams had raced outside Europe before – notably in Colombia and the United States – but persuading a team of ONCE’s prestige to make the long haul to Australia at the beginning of the season was a new departure. “It was really was seen as the other side of the Earth back then,” Jonker says. “Tour de France riders didn’t come Down Under.” Even so, the financial outlay from the organisation was minor. “I think we just helped out with a place to stay,” Trevorrow explains. “It was Neil who convinced them to come out here, like a training camp.”

Stephens’ standing at ONCE was such that he already had Saiz’s blessing to spend the entire off-season in Australia. “I went to the January training camp once or twice, but then I started to skip it because I could train better in Australia,” Stephens said. It helped to have a manager who placed such trust in his riders. After two years under Peter Post’s constant surveillance, this was altogether new to Jonker. “If his people hadn’t seen you out training on the roads in Belgium or Holland, he’d be ringing up to know where you’d been,” Jonker says.

In December 1994, Stephens and Jonker trained in Canberra and Adelaide, respectively, before linking up in Melbourne with the Spanish contingent: a mechanic, soigneur and directeur sportif, as well as two riders, Herminio Díaz Zabala and the young talent Mariano Rojas, who would be killed in a car crash the following year at just 23 years of age. The five-man ONCE squad was completed by a local guest rider, Eddy Salas, and they are listed in the Canberra Times account as the ‘Abom-Mount Buller’ team. “We had a bit of a composite team and asked Eddy to come in with us,” Stephens says. “He was a great young bloke.”

Although ONCE had a flatter leadership structure than most teams at the time, there was a distinct hierarchy for the Summer of Cycling. “Neil was the number one Aussie with the most experience, so we did everything we possibly could to help him win,” Jonker says. The opening event, the Bay Classic, could hardly have gone better. Stephens won three races and the overall standings, marking himself out as the favourite for the following Melbourne Classic. The man who won the final leg of the Bay Classic, however, had other ideas.

Robbie McEwen probably should have been a pro rider by January 1995, but the rhythms of Australian cycling were changing. A man could now be blooded in European racing while still operating within the structures that were being erected back home.

In 1994, McEwen had travelled to Europe with the Australian national team and notched up a hat-trick of stage wins at the Peace Race, before adding another at the Tour de l’Avenir for good measure. The biggest teams were aware of his talent, but he stayed for another year in Salzwedel’s AIS set-up before making the step up with Rabobank in 1996.

After beginning in BMX and then being cut from the AIS track programme in 1992, McEwen had fashioned himself into the coming man of Australian road cycling. A blistering finisher with preternatural race craft, the 22-year-old’s ability had not gone unnoticed by Stephens, who often trained with the young AIS cohort in Canberra during the off-season.

He got to observe McEwen at closer quarters in the Melbourne Classic, where the Australian professional title was also on the line. The event started in the Botanic Gardens before heading for the hills around Geelong and then returning to Melbourne by way of the West Gate Bridge. “That had never been allowed before,” Trevorrow says proudly. ONCE proceeded to shred the peloton in the crosswinds approaching the West Gate Bridge, and McEwen, who had just returned to the bunch after suffering with intestinal issues, was the only man able to follow Stephens and Díaz Zabala when they punched clear.

“Racing against them I was like an excited kid,” McEwen told Trevorrow’s DeTour podcast recently. “Well, I was an excited kid.” Even so, he had the sangfroid of a veteran. He sat on the ONCE duo all the way into Melbourne, deftly parried their attacks on the two laps of the Botanic Gardens that followed, and then dispatched them in a sprint.

“I ended up just pipping Díaz Zabala in the sprint – by about fourteen lengths,” McEwen deadpanned, though the national title went to Stephens, the best-placed Australian professional on the day.

“Robbie won the race, but I was the national champion because he wasn’t a pro rider,” Stephens says. “But that was the thing – this young fella was obviously going to set the world on fire.”

The Abom Mount Buller Cup, held in north-eastern Victoria, was the final instalment of the Summer of Cycling, and the dramatis personae was the same as in the previous events in the hinterland of Melbourne, with ONCE again facing the best domestic professionals and promising amateurs in Australia.

Some familiar names populate the 70-strong start list. As well as McEwen, Stephens and Jonker, competitors included future Mitchelton-Scott directeur sportif Matt White, future Giro d’Italia stage winner David McKenzie and future Olympic Madison champion Scott McGrory. But for injury, future SBS Tour de France commentator Matt Keenan would also have raced.

“I rode the Summer of Cycling the year before and the year afterwards,” Keenan tells Cyclingnews. “We didn’t realise it at the time, but it was a significant turning point for Australian cycling. Before that, road cycling was in our winter, and the races were Aussie against Aussie. So to have ONCE come in 1995 was the equivalent of Ineos landing today on the doorstep of a country that didn't have much international cycling."

The ONCE cohort immediately installed themselves atop the classification in the short, opening time trial at Mount Buller. Stephens claimed the stage, 10 seconds ahead of Díaz Zabala and 14 up on Jonker, with Marcel Gono (later of Credit Agricole) taking 4th. That afternoon, the first road stage saw the peloton drop towards the finish on the Wangaratta velodrome, where McGrory’s track nous carried him to victory ahead of Dutchman Harm Jansen. “It was a bit like the Paris-Roubaix finish,” Trevorrow says.

A quarter of a century on, Stephens can’t quite recall whether he lost the overall lead to his teammate Díaz Zabala in Wangaratta or the following day at Mansfield, where McEwen won, but his memory of the circumstances is perfectly clear. Inevitably, McEwen was the catalyst: rather than endure ONCE’s likely collective onslaught, he elected to anticipate it by attacking early. “Robbie’s such a smart bloody bike rider,” Stephens says. “He made sure he got Herminio in the move with him, too, and the break hung on to the finish.”

Stephens returned to the overall lead in Yea on stage 4 after punching clear to win from McKenzie and White, but McEwen continued to put up unwelcome resistance to ONCE’s dominance. “Little McEwen kind of pissed us all off,” Jonker laughs. “I think that was a sign of things to come, really…”

On stage 5 to Marysville, McEwen once more found himself off the front with ONCE’s strongmen for company, though again, the scant published information doesn’t entirely tally with the memories of those involved. Jonker definitely won a stage of the Mount Buller Cup, but neither he nor Stephens seem sure if it was this one, despite what Cycling Archives and the Canberra Times say. Stephens is certain, however, of what befell McEwen when he rode towards Marysville with two – or three – ONCE riders for company.

“The way I remember it, it was just Herminio and me. We were trying to one-two Robbie again at the finish,” Stephens says. “But because Robbie’s a smart guy, he thought, right, I’ll control it from the front. Then we came down this hill and there was a marshal in the middle of the road at the bottom clearly indicating we had to go left, but Robbie went right. Herminio and me kept quiet. We just laughed and went left…”

ONCE claimed the stage – Cycling Archives has Jonker winning by 37 seconds from Díaz Zabala and Stephens – while an incandescent McEwen was left to complain to the commissaires when he eventually found his way home. “I can still remember him, he was going ballistic,” Trevorrow laughs. Sympathy was in short supply at ONCE. “We wouldn’t have felt sorry for him,” Jonker says. “All the amateur riders wanted to show how good they were and beat us. It was probably harder than racing against other pro teams. In a way, we were happy to go back to Europe.”

Before they did, there was one stage of the Mount Buller Cup remaining. Nobody, not even McEwen, could dare to dream of weathering ONCE’s assault on the 15km haul up Mount Buller itself. “They tore us apart,” McEwen said. “They were one, two and three on the stage.”

Díaz Zabala triumphed at the summit in the same time as Stephens and Jonker, and that trio also stood atop the final podium. Stephens sealed overall victory, 30 seconds ahead of Jonker, with their Spanish teammate third at 52 seconds. ONCE’s Australian expedition had been a resounding success. They would continue in the same vein all year, culminating in Jalabert’s dominance at the Vuelta a España in September.

As its faint internet footprint demonstrates, the 1995 Mount Buller Cup didn’t alter the sport overnight, but, 25 years on, the significance of its role as a catalyst can be seen in rather sharper focus.

Just as most of the makers of Manchester’s 1980s music scene were among the sparse crowd at the Sex Pistols gig at the Free Trade Hall in June 1976, it is striking that so many of the protagonists of Australian cycling in the 21st century were involved in the Summer of Cycling in 1995, either as riders, organisers, coaches or sponsors.

“When you look back at that race, its impact on Australian cycling was huge,” says Stephens, who traces the genesis of both the Tour Down Under and the Mitchelton-Scott team to the event. “It was the first big road race in the middle of the summer in Australia and that later led to the Tour Down Under. And, as far as I’m concerned, it was the first event that turned into what later became Mitchelton-Scott.”

Trevorrow downplays his own role in the development of the Gerry Ryan-backed GreenEdge project – “Officially, I’m team mascot” – but he concedes that the Summer of Cycling built momentum for what followed. Ryan’s involvement intensified after 1995: he began sponsoring the Australian Institute of Sport, and the Summer of Cycling expanded to incorporate a new event, the Jayco Tour of Tasmania. In 1998, a mountain biker called Cadel Evans beat Stephens to the overall title in Tasmania, before turning full-time to the road at the turn of the decade.

By then, the gap between Australia and the rest of the international calendar had been bridged more permanently with the establishment of the Tour Down Under, held for the first time in 1999. Just three years after Díaz Zabala and Rojas blazed a trail by boarding a flight to Melbourne, ten European teams followed in their path by travelling to Adelaide. Since 2009, Michael Turtur’s race has been the first event on the WorldTour calendar. It might never have happened had Trevorrow’s Summer of Cycling not shown what was possible.

“It proved to European teams that they could go to the other side of the world and have good preparation for the year,” says Jonker, who brought the curtain down on his own career by winning the overall title at the 2004 Tour Down Under while riding for the UniSA–Australia squad. “I won the Route du Sud and some smaller stage races, but nothing compares to winning at home."

McEwen echoed that thought when he landed the first of his dozen Tour de France stage wins on the Champs-Élysées in 1999. A familiar voice piped up from the scrum of journalists that tightened around him at the finish. “How does this compare to winning the last stage of the Bay Crits?” asked Trevorrow. McEwen smiled: “Nearly as good, John. Nearly as good.”

When McEwen retired in 2012, it was in the colours of GreenEdge, where Stephens was part of the management team. Stephens’ racing career effectively ended with his implication in the Festina Affair on the 1998 Tour de France, when he admitted to French police that he may have been administered EPO but claimed it was done without his knowledge. “It was going to finish sooner or later. With what happened in 1998, it did finish then,” Stephens says now.

He raced just once more after that Tour, for Australia at the 1998 Commonwealth Games in Kuala Lumpur, where he was selected by national coach Shayne Bannan despite public objections from figures such as Australian IOC member Phil Coles. Stephens says he never considered leaving cycling after the Festina Affair. “No, I didn’t. At the end of ‘98, I was in a bit of limbo,” he says. “But cycling is something I always wanted to be a part of, and I also wanted to be involved with Australia.”

Bannan helped to keep Stephens involved in the years that followed, handing him a position – unpaid at first – as a conduit between the Australian cycling federation and the European-based professionals. He continued in the role during his stints as a directeur sportif at Liberty Seguros, Astana and Caisse d’Epargne, before resigning when he and Bannan worked to establish GreenEdge ahead of their debut season in 2012.

When GreenEdge entered the peloton that January, their first races were on home roads, beginning with the Bay Classic, still organised by Trevorrow. If the ‘Summer of Cycling’ tag was no longer in use, it was only because it was by then redundant: every summer in Australia was now a summer of cycling.

The wider cycling world, meanwhile, has grown both larger and smaller since 1995. The peloton travels further to race than ever before, but the distances from one cycling culture to the next have been shortened immeasurably as a result. The Mount Buller Cup played its part in that process. Information about the event was in short supply a quarter of a century ago, but it left a legacy all the same.

Mount Buller Cup. January 28-February 1, 1995.

| # | Rider Name (Country) Team | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Neil Stephens (Aus) | 0:04:46 |

| 2 | Herminio Diaz Zabala (Spa) | 0:00:10 |

| 3 | Patrick Jonker (Aus) | 0:00:14 |

| # | Rider Name (Country) Team | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Scott McGrory (Aus) | 3:04:14 |

| 2 | Harm Jansen (Ned) | |

| 3 | David McKenzie (Aus) |

| # | Rider Name (Country) Team | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Robbie McEwen (Aus) | 3:18:52 |

| 2 | Harm Jansen (Ned) | |

| 3 | Scott McGrory (Aus) |

| # | Rider Name (Country) Team | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Neil Stephens (Aus) | 3:18:37 |

| 2 | David McKenzie (Aus) | 0:00:31 |

| 3 | Matthew White (Aus) |

| # | Rider Name (Country) Team | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Patrick Jonker (Aus) | 4:31:48 |

| 2 | Herminio Diaz Zabala (Spa) | 0:00:37 |

| 3 | Neil Stephens (Aus) |

| # | Rider Name (Country) Team | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Herminio Diaz Zabala (Spa) | 3:57:11 |

| 2 | Neil Stephens (Aus) | |

| 3 | Patrick Jonker (Aus) |

| # | Rider Name (Country) Team | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Neil Stephens (Aus) | 18:50:30 |

| 2 | Patrick Jonker (Aus) | 0:00:30 |

| 3 | Herminio Diaz Zabala (Spa) | 0:00:52 |

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.