Nelson Vails: The Harlem kid who became US cycling's first Black Olympic medalist

Track sprinter would like to see legacy live on with the recognition of a new generation of talent

February is Black History Month in the United States and Cyclingnews will be featuring stories both looking back at Black accomplishments in the sport and toward the future. In this feature, we check in with Olympian Nelson Vails.

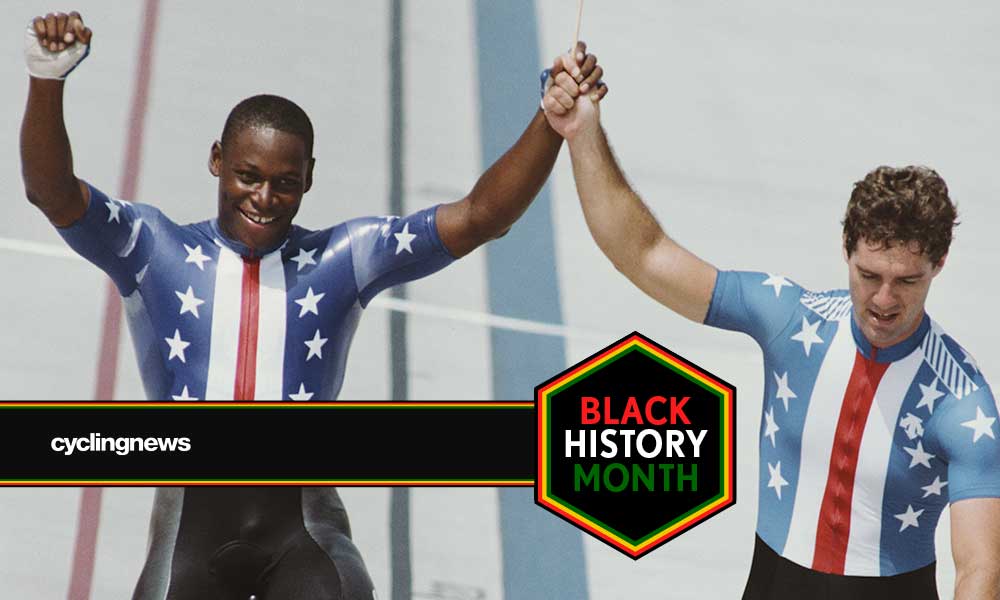

In the world of cycling, Olympic medalists are rare, and medalists from the United States even rarer. But Nelson Vails is a one of a kind: the first, and only, Black Olympic medalist from the USA in cycling, with silver in the individual sprint behind teammate Mark Gorski in Los Angeles in 1984.

The 60-year-old still spends his days trying to motivate people of all colours and ages to stay active by hosting bike rides and sharing the story of his remarkable rise to fame.

Vails, the youngest of 10 children growing up in Harlem in New York City, overcame great odds to find his calling on the bike. Just a few months before his birth, his older brother was murdered on the family's front steps.

Vails admits he grew up "a spoiled brat" as a result but he also had a close-knit family who looked out for him. He grew up during the civil rights movement but says he remained shielded from racism and discrimination, forging a laser-focused trajectory from Central Park to the Los Angeles velodrome.

"As a young African American kid growing up in Harlem, people live to tell their sad stories of discrimination. Anyone who was looking after me made sure that I didn't see that, it's like parental guidance on TV channels for your kids," Vails explains to Cyclingnews.

"You just don't want them to go there. I think I was always removed from any bad energy of discrimination growing up."

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Vails says he was a "bad kid" but that all changed when he got his first bicycle from members of a motorcycle gang he hung out with: a Peugeot that he then rode every day in Central Park. At 17, he got a job as a bicycle messenger, spending every day darting through New York City traffic, honing the very skills that he would soon use on the velodrome.

His success seemed to come overnight. Before long he was racing on the Kissena Velodrome and being bused to Trexlertown to race, winning local criteriums and road races. He joined the Toga Tempo Thunderbolts team sponsored by Manhattan bike shop owner Gaylen 'Lenny' Preheim, and was kitted out in the distinctive green and gold colours of that team. He became the New York State sprint champion, earning a berth at the national championships.

From there, his talent brought him to the Olympic Training Center in San Diego in 1980, where Eddie 'B' Borysewicz took his raw talent and moulded it into a champion's form and mentality.

Borysewicz had a knack for bringing out the untapped potential in his athletes and knew just how to steer them toward success, Vails says. "He'd send you to races where you build confidence... he'd send people to races where you should win because of the training he put you through. Then you have hope and confidence.

"That's where I really developed from his mentality of teamwork. Although you're an individual, you do your job and the whole team is [cohesive] together because everybody on the team is doing their job."

Throughout his rise to the status of national champion, Pan American champion (1983), to Olympic medalist (1984), Vails says he was always welcome and never felt excluded because of the colour of his skin.

"Being an overachiever, I was always welcome. I was never excluded. I was always included," he says.

Some athletes might look at getting second place in the biggest event of their career as a failure, but Vails embraced the success as an Olympian and a medalist and an inspiration to his hometown and country. It didn't hurt that his loss came at the hands of a teammate, and he is careful to attribute his achievement to his team, his family and his upbringing.

"I went through my Olympic medal life where it wasn't just me, I shared it with everyone [and was] very touchable about it," he says. "Not only did I and my teammates perform, but it just made for a great day that the home team was winning. What me and Gorski did, Steve Hegg and [Lennard] Nitz (gold and bronze, individual pursuit) and you know, I can go on and on."

The US brought home nine cycling medals that year, including gold medals in the men's and women's road races. "That momentum carried on throughout the team."

The one day in Los Angeles gave Vails the title of Olympian, one that he takes seriously and carries with him every day.

"It was all part of the plan of achieving, once I learned that I had a talent... and learned to harness it, then it bloomed from there. Part of the programme was being prepared for overnight success. So you sign every autograph, you take every picture, you smile, even when you don't feel good."

Any sportsperson who doesn't want to go through the attention, interviews and autographs, he says, should just not win. "If you want to win, get ready. For example in the Tour de France, the stage winner and a yellow jersey holder, pretty much all the jersey holders, they get to the hotel last. They get to the dinner table last because they got to do all the interviews and press conferences, and talk to everybody from the podium, all the way to the hotel lobby before they can go change, get their massage, go get something to eat.

"It's hard. It comes with the success. That's part of the territory. And you can get burnt out, but then you probably need someone like me to talk you through it and say, 'Hey, stop winning.' Then, if you don't want to do that, smile, suck it up. Let's win some more. Let's train hard so you can keep doing this.

"I wanted to do the interviews. I wanted to get my picture taken. So if I train I can do this again and again and again. And that's what I did. For as long as it lasted."

Leaving a legacy

Vails continued to race, but after not making the 1988 Olympic team, he headed to Europe to race professionally on the Six-Day circuit and in Japan in Keirin racing until he retired in 1995.

He says he tried to get on the coaching staff at USA Cycling and had the support of former coach Chris Carmichael, who tells Cyclingnews, "I had known Nellie since 1978 and seen him develop into a great sprinter. Even more than that, he was a great person, had been a world-class sprinter for a long time, and he had an eagerness to learn. USA Cycling was looking at hiring a sprint coach from the Australian program, which was a very successful program at the time.

"My recommendation to USA Cycling was to bring Nellie on to learn and develop as an assistant coach under the Australian head coach for an Olympic cycle, with the long-term vision that Nelson would take over the sprint track program to develop the next generation of American sprinters. It didn’t seem like my idea was taken seriously, there just didn’t seem to be much interest in it from the people I talked to at USA Cycling."

Vails wouldn't go on the record on his opinions about USA Cycling's snub other than to criticize how the men's track sprinting programme – which carried on with riders like Marty Nothstein, Erin Hartwell, then Giddeon Massie (the last Black cyclist to race for the US in the Olympic Games cycling events in 2004 and 2008) – seems to have died away.

"I retired and left the sport, and didn't have an opportunity to work for USA Cycling during that time, to translate my talent to the next generation of Olympians. So, I left. I travelled the world, I went and did other stuff. So now I'm an old dude with a nice bike with my name on my clothes."

Vails fills his day with rides around his neighbourhood in southern California, and, before the pandemic, with public speaking and leading rides across the country. His last group event in Florida came as the pandemic began shutting down gatherings across the country, and he's not sure when he can get back to it.

"I don't want to involve myself in any group activities just yet, I would like to fill my calendar. I just learned some bad news last week that my New York homecoming Gran Fondo event has been postponed to 2022."

When asked what he would like his legacy to be, Vails expressed the only regret of the interview.

"I would like, maybe someday – since I haven't really pushed hard enough – to create a Nelson Vails cycling club or team," he said.

"I would like to see my legacy live with a new generation of kids of all colours and ethnic backgrounds to really harness their talent and recognise it at a young age and take advantage of it."

Laura Weislo has been with Cyclingnews since 2006 after making a switch from a career in science. As Managing Editor, she coordinates coverage for North American events and global news. As former elite-level road racer who dabbled in cyclo-cross and track, Laura has a passion for all three disciplines. When not working she likes to go camping and explore lesser traveled roads, paths and gravel tracks. Laura specialises in covering doping, anti-doping, UCI governance and performing data analysis.