Morzine and the Col de Joux Plane

A fitting finale for the 2016 Tour de France

So here we are then. It comes down to this. One last day in the Alps. You'd be hard-pressed to design a better stage for a thrilling finale to a Tour de France – the only problem is the fight for the yellow jersey has long since lacked any real suspense.

Or has it? Chris Froome crashed in the rain yesterday and had to dig in deep on the final climb having taken a bash to his knee. With more climbs, more descents and more downpour on the menu this afternoon, it might not, after all, be over until it's all over. Up until yesterday, it had become increasingly clear that this Tour has been ridden 'à deux vitesses'. Froome, as Eddy Merckx noted on Thursday, has been in a league of his own – the strongest man in the race and the man with the strongest team in the race.

He still has a lead of more than four minutes, and this is still ostensibly a race for the podium, but it is nevertheless uncertain how the hangover will be after the mini ordeal yesterday. In any case, the action in the shadow of Mont Blanc seemed to reawaken a Tour that had been in danger of sleepwalking its way to Paris after the second rest day.

An open contest, a dash of tension, and a sense that anything could happen are certainly ingredients the race directors had in mind when drawing up the parcours for today's climax.

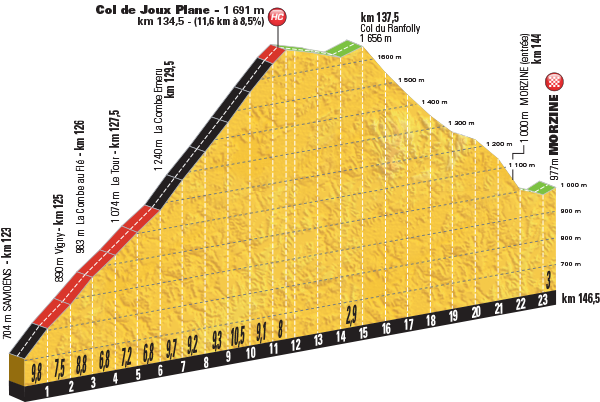

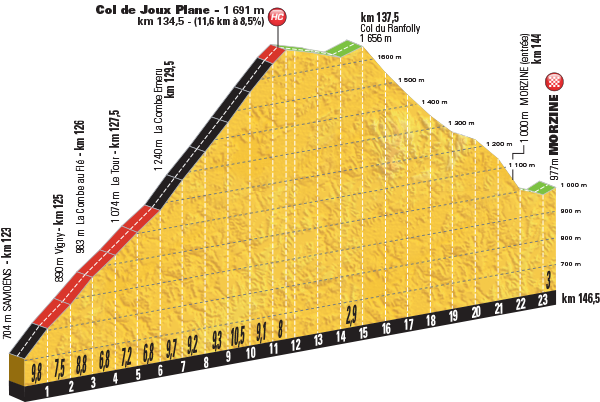

It's a short and potentially explosive mountain stage – as seems to be the fashion these days – with a descent to the finish. 146.5 kilometres linking Megève and Morzine, it takes on some pretty serious mountain passes in the form of the Aravis, the Colombière, and the Ramaz. But it's the final hors-catégorie climb of the Col de Joux Plane and the subsequent white-knuckle descent into Morzine that's the centrepiece here.

The Joux Plane-Morzine combination is something of a classic, despite only having featured in the Tour 11 times. It made its debut in 1978 but wouldn't really be seen until two years later, as the weather closed in and prevented the television images from being transmitted. Christian Seznec won that day but a 23-year-old Bernard Hinault was on his way to the first of five Tour de France titles – two more of which would see him cover the same roads.

More on this article:

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

- Quintana, Morzine and the echoes of 'Lucho and Parra'

- Tour de France: Chris Froome survives crash, finishes on Thomas' bike

- Tour de France 2016 Stage 20 preview: Megève - Morzine, 146 km

Many more memorable storylines have followed. Marco Pantani skipped away from Jan Ullrich in 1997 to set the record time for the climb – a scarcely believable 33 minutes – and raise his arms in Morzine, though he would have to wait another year to get his hands on the yellow jersey.

In 2000, French housewives' favourite Richard Virenque pulled off the same feat, hurtling down the mountain while the climb was playing host to a rare sight of that era – Lance Armstrong cracking.

There are nothing but unhappy memories for Pedro Delgado, who lost 25 minutes suffering from stomach problems in his first-ever Tour in 1983, and broke his collarbone on the descent the following year. In 1987, wearing the maillot jaune, he was dropped on the descent, losing 18 seconds to Stephen Roche in what was a portent of the swinging balance of the race. The Spaniard would win the Tour for the first and only time the following year and, though there was a finish in Morzine, there was, mercifully, no Joux Plane.

The treacherous descent was unhappier still for Carlo Tonon, who crashed and spent two months in a coma, suffering permanent brain damage and taking his own life 12 years later.

But one episode stands out above all others: Floyd Landis in 2006.

It's 10 years since the American produced one of the most staggering performances the Tour has ever seen – that's the longest the race has ever gone without the Joux Plane-Morzine combo since its debut, and perhaps it has needed that space to recover from the scarring impact of what proved to be a farcical, drug-fuelled day in the Alps.

Landis' race was in tatters; he had started the previous day in yellow but cracked in dramatic fashion on La Toussuire and lost over 11 minutes. His race was over. What he did next defied logic.

Going solo from some 120km out, he picked off the breakaway riders as he furiously made his way over four Alpine climbs. By the time he hit the Joux Plane, there was real panic in the eyes of race leader Oscar Pereiro, but it wasn't just the dithering of the yellow jersey group that made the feat possible; Landis had nearly four times the permitted testosterone levels coursing through his blood stream and he tackled the Joux Plane as if it wasn't there. He hit the line in Morzine several minutes ahead of the favourites: Back from the brink.

The resurgence paved the way for Landis to take yellow in the time trial and top the podium in Paris, although one of cycling's most memorable comeback fairytales was proved to be just that – nothing more than a fiction – as the American was exposed just four days later.

10 years since one of the episodes most emblematic of cycling's ills – there may not be any significance to the round number, but it's about time the Joux Plane and Morzine were purged in some way of the association.

Up and down

Col de Joux Plane: 11.6 kilometres at an average gradient of 8.5%

Although the Tour has its climbs of greater fame and legend, Daniel Friebe, in his book Mountain High, discusses whether the Joux Plane is among the toughest, and he quotes Peter Winnen, who won in Morzine when the climb was used in 1982, as saying it's "the nastiest climb in the Alps".

The southern ascent starts out from the Savoyarde town of Samoens and immediately signals its intent with pitches that enter the double digits.

The roads are narrow, cut into the meadow as they wind up through the mountainside. Besides a brief respite after the early sting, there's no real let-up to speak of, and it's not as if the riders can settle in for a steady grind because the gradients change regularly.

The second half of the climb is the hardest, with a five-kilometre stretch where the average gradient is nearly 10 per cent. This is where the road enters the trees, through which glimpses of Mont Blanc begin to appear on a clear day.

There's a lake at the summit and the road begins to dip down, but it actually kicks back up again before the start of the descent proper, with riders having to get out of the saddle once more to hit the Col de Ranfolly.

From there they'll peel off and head down what in the winter is a leisurely blue ski slope through the trees, called 'Le Choucas' (The Jackdaw') – read into that whatever metaphor you will.

On a bike and on the tarmac, It's a white-knuckle ride, not your run-of-the-mill hairpinned descent, but a fast and technical affair, full of irregular bends – some swooping, some tight, some blind – and long straight sections where you really pick up speed. One story – fact or urban myth? – has it that Sean Kelly once clocked 124km/h.

The road dips down even more vertiginously as it nears the town centre and no sooner than it levels out has it kicked up again for a leg-sapping dash up to the finish line at Morzine's tourist office.

There are multiple points on every Tour route that adopt the adage of being places where a rider might not be able to win the race, but can certainly lose it. Joux Plane-Morzine is one such example. If ever there was a descent that warranted a reconnaissance, coming as the final act in the Tour, it is this one. Indeed, Froome and most of the other GC contenders took the time to check it out ahead of July and Nairo Quintana will have very clear memories having taken his first WorldTour win here at the Dauphiné in 2012.

But will there be enough pressure on Froome to make a spectacle of it?

You sense that to get the best out of Joux Plane-Morzine you'd ideally have a race that was balanced on a knife-edge, with high stakes and much to gain. If Froome crests the climb with everyone else then he'll be able to approach the descent with a relative sense of calm. Over to the others, then, to take the race to Sky and test Froome well in advance.

It may seem unlikely that the maillot jaune can be wrestled from Froome's skeletal frame, but stranger things have happened, and let's not forget that the last two Grand Tours have seen victory snatched from the jaws of defeat.

Patrick is a freelance sports writer and editor. He’s an NCTJ-accredited journalist with a bachelor’s degree in modern languages (French and Spanish). Patrick worked full-time at Cyclingnews for eight years between 2015 and 2023, latterly as Deputy Editor.