Monte Zoncolan: A ride to resurrection - Preview

'It leaves you tired but buzzing with emotions' says double winner Gilberto Simoni

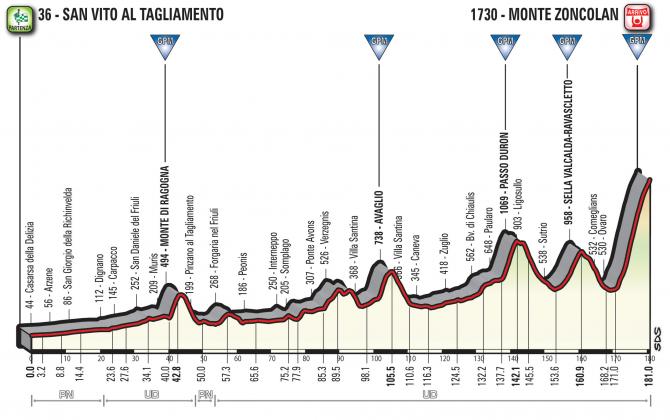

After two sprint stages on flat roads from central Italy to the northeast, the Giro d'Italia heads deep into the mountains on Saturday with the terrible Monte Zoncolan as the first part of a weekend double whammy of climbing.

The locally called 'Kaiser' dominates the Carnia mountains in the Friuli region close to the border with Austria and Slovenia. It is neither long nor high, but it is steep – very steep – with the 11.9 per cent average and sections at 20 per cent earning the Zoncolan the title of hardest climb in Europe.

The Zoncolan will test the riders' strength, climbing ability, and determination. For many, it will be easier to quit than to ride on, with the riders of the gruppetto making it to the finish thanks to 'help' from the tifosi that pack the roadside, ready to give anyone who needs it a bit of a push.

With everyone at their physical limits, there is little room for race tactics amongst the overall contenders. Any time gaps may not be huge, but the Zoncolan will have, like always, a significant impact on the 2018 corsa rosa.

There are 100,000 people expected to watch the stage on the steep slopes, with many packing the open-air natural stadium created by the mountain slope that overlooks the final 500 metres of the climb. It is a celebration of professional bike racing.

The Giro d'Italia will climb Monte Zoncolan for only a fifth time in its history on Saturday during stage 14, but it has already become legendary.

Fabiana Luperini first conquered it in the 1999 women's Giro Rosa. Gilberto Simoni was the first man to win at the top after climbing from the 'easier' Sutrio side in 2003. Simoni won again in 2007, climbing from the harder and steeper Ovaro side, which was also covered in 2010 (won by Ivan Basso), in 2011 (Igor Anton) and won by Michael Rogers in 2014.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

This year's 180km stage ends with the climb from Ovaro but also includes the short but steep Passo Duron with 40km to go and then the Sella Valcalda Ravascletto. A fast descent via Comeglians takes the riders to the foot of the Zoncolan. The final two hours are a roller coaster of pain.

"It's a very hard stage, because even though the climbs are not high, they are steep. It's the first real test of the final battle of this year's Giro d'Italia," race director Mauro Vegni explained.

"The Duron is only four kilometres long but climbs at an average of nine per cent, and the first kilometre has a section at 18 per cent. Ravascletto is seven kilometres long at seven per cent. The Zoncolan is 10 kilometres at 12 per cent, with several points at two per cent.”

The Giro d'Italia race book, much like weather forecasts, uses shades of yellow and orange to highlight the gradients. The Zoncolan is a long strip of dark red, with only brief easier sections at the start and near the finish. A four-kilometre first section climbs at 15.4 per cent, with a further two kilometres at 13.9 per cent. Only the final two kilometres ease with the gradient in single figures but still at 8.9 per cent as the finish line appears.

At the start of the Zoncolan, the riders pass under a sign that reads 'Benvenuti all'inferno! – Welcome to Hell!'. The suffering only ends after the final tunnel 500 metres from the finish when the bright light of the mountaintop appears like a sense of resurrection.

Riders are forced to use ultra-low gears with most opting for a compact crankset with 36 or even 34-tooth chainrings and huge cogs down the back. Chris Froome is expected to use a 32 cog so that he can somehow spin his legs in the hope of limiting his losses to race leader Simon Yates (Mitchelton-Scott) and his now biggest rival Tom Dumoulin (Team Sunweb).

Yates suggested that time gaps could be small due to the climb becoming an individual fight against the gradient. However, Froome suggested that time gaps could be big, especially if some riders suffer on the Duron and Sella Valcalda Ravascletto. Rain is likely and could add further difficulty to an already terrible day.

Simoni: I went on the front and never looked back

Simoni became a national hero in Italy when he won on the Zoncolan and went on to win the Giro d'Italia in 2003. Now 46, he will return to ride the Zoncolan, 230km from his home in Palu di Giovo near Trento, and celebrate in Ovaro at the foot of the climb. Like thousands of others, he hopes to ride to the finish before the professionals do.

Simoni has coined a simple but effective way of explaining just how hard the Zoncolan is: "The easiest part equals the hardest climb of the Tour de France."

"It's not the Pordoi, it's not the Stelvio and not even the Mortirolo, the Finestre or the Angliru," Simoni explained to the Corriere della Sera newspaper, making it clear that the Zoncolan is incomparable with any other climb.

"It's a forest track; it's fascinating, and yet is a place where tactics count for little. I just went for it, without thinking. I went on the front and never looked back.

"I reached the final tunnel with my heart in my mouth. When you come out into the light, it's a spiritual feeling. The dark is terribly dark, and then the light is violent, but you're welcomed by an immense cheer from the crowd. I can still hear it now. It's like scoring a goal in a packed football stadium. It leaves you tired but buzzing with emotion."

Stephen is one of the most experienced member of the Cyclingnews team, having reported on professional cycling since 1994. He has been Head of News at Cyclingnews since 2022, before which he held the position of European editor since 2012 and previously worked for Reuters, Shift Active Media, and CyclingWeekly, among other publications.