Moment of truth – The Puy de Dôme and the Tour de France’s greatest duel

Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor go elbow to elbow in 1964

In Paris in the summer of 2001, the Luxembourg Gardens served as the site of an exhibition showcasing the greatest sports photographs of the 20th century. 100 images were displayed along its green railings, from fencing to football, from Alain Prost to Zinedine Zidane, but one picture drew more footfall than any other: Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor, elbow to elbow on the Puy de Dôme, locked in combat for the 1964 Tour de France.

Each evening, the pavement around the perimeter of the gardens was blocked by the masses who found themselves inexorably drawn to the image, pausing to gaze at the two figures in hushed silence as though contemplating a religious icon. In some ways, perhaps they were.

The photograph has a prose counterpart in the oft-cited words of race director Jacques Goddet after he had observed the contest at close quarters: “Their breath, their sweat, and the wool of their jerseys mixed.”

Much in like epic poetry, hand-to-hand combat has provided much of the most enduring passages from Tour history, and Anquetil and Poulidor’s contest outshone all others, reaching its apotheosis in the most striking way imaginable, on the extinct volcano of the Puy de Dôme just two days from Paris.

Over the years, it became an article of faith that Anquetil versus Poulidor was the Tour’s perfect duel and 1964 the race’s greatest edition. In 2004, a panel led by former Tour director Xavier Louy deemed it to be just that, and no other edition of the race has inspired quite the same mountain of prose as Anquetil’s fifth overall victory (or, depending on your point of view, as Poulidor’s most famous defeat). Barely a summer goes by without a new addition to an already extensive library. For so many French authors, writing of Anquetil and Poulidor mirrors how their counterparts across the Atlantic tackle Ali or DiMaggio. They are rarely writing about sportsmen so much as about a country and a place in time.

In 1964, France was a whole divided in two parts, one of which was occupied by anquetilistes and the other by poulidoristes. Their divergence in style and reputation of their two idols was mirrored in the clash between their nicknames. In one corner, the hauteur of ‘Maître Jacques.’ In the other, the more everyman charms of ‘Poupou.’

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Both were of farming stock, but it was the differences between them that always stood out: Anquetil was slender, blonde and reserved, Poulidor robust, dark-haired and affable. Anquetil’s Saint-Raphael team was managed by the era’s innovator, Raphael Geminiani. Poulidor served under the more traditionalist Antonin Magne at Mercier. Anquetil was a serial winner, winning the first of nine Grand Prix des Nations at 19 and landing his first Tour as a 23-year-old debutant in 1957. Poulidor would retire as ‘The Eternal Second’ after placing on the Tour podium no fewer than eight times.

Inevitably, the two rivals came to serve as symbols of their times. “Politically, and without it being necessarily rational, Anquetil was the incarnation of the realist and triumphant right,” the Jacques Augendre wrote in Anquetil-Poulidor, Un Divorce Français. “Poulidor reflected the left, more popular but less successful.”

Almost six decades on, Anquetil and Poulidor’s respective legacies are long since set in stone, frozen in time like the image atop this page. In the summer of 1964, however, Poulidor, two years Anquetil’s junior, was riding only his third Tour de France, and the cement on his reputation as the great nearly man of cycling hadn’t even begun to harden into fact.

Although Poulidor had taken a sound beating at Anquetil’s hand in the 1962 Tour, most notably he was caught and passed in the Lyon time trial, his star was still on the rise when he arrived in Rennes for the Grand Départ two years later. That spring, after all, he had taken victory at the Vuelta a España.

Anquetil, on the other hand, had already won a record four Tours, and in June 1964, he had claimed his second Giro d’Italia. Now he was seeking to emulate Fausto Coppi by becoming only the second man to pull of the Giro-Tour double, but his exertions in Italy had left him in a rather more vulnerable state that he would care to admit in July.

In hindsight, the 1964 Tour would mark something of a turning point in the history of the race, arriving at the very tail-end of the sepia-tinted ‘golden age’ of the post-war years. In that era, news of the action was relayed primarily by newspapermen and radio commentators. Even though limited live television coverage had been rolled out by 1964, for most of France, the Tour was still an event more imagined than witnessed.

Therein, perhaps, lies some of the enduring appeal of the 1964 Tour. The defining duel was already compelling, and the margins were remarkably tight, but the epic dimensions of the race were still permitted to take root in the mind rather than find themselves cut down to size by the tyranny of hours upon hours of television coverage.

Poulidor’s existence as the sine qua non of star-crossed Tour contenders began in earnest on stage 9 to Monaco where he made the error of sprinting for victory a lap too early, only for Anquetil on the final circuit of the track to claim the stage win and, with it, a one-minute time bonus.

Anquetil, the epitome of consistency, proceeded to win the time trial two days later, while reputation as a bon vivant and penchant for superstition came to the fore when the race broke for its rest day in Andorra. At the suggestion of Geminiani, Anquetil eschewed a rest day ride and attended a méchoui organised by Radio Andorra, posing for a photograph with an enormous leg of lamb and a glass of wine.

That decision looked to come back to haunt Anquetil when he was distanced on the opening climb of the Envalira the following morning, while popular legend insists that his initial reticence on the descent was triggered by the prediction of a ‘seer’ named Belline that he would die in a fall on the stage. Aided by some choice words from Geminiani, however, Anquetil spluttered back into action on the descent, swooping down the other side to save his Tour challenge.

By day’s end, Anquetil would even have gained 2:36 on Poulidor, who suffered a disaster in two acts in the finale of the stage, first by breaking a spoke and then crashing immediately after changing the wheel. Still, a solo victory at Luchon the next day brought him back to within just nine seconds of Anquetil, but there was still more misfortune to follow. In the Bayonne time trial on stage 17, Poulidor suffered a puncture and then endured a comedy of errors during his bike change.

And yet Poulidor still did more than enough to keep himself in the hunt. Even with the mishaps, he somehow limited his losses on the stage to a mere 37 seconds leaving him just 56 seconds behind an apparently flagging Anquetil in the overall standings. Despite his spate of misfortune, Poulidor increasingly gave the impression of being the stronger man and, two days from Paris, he had a shot at victory on what effectively amounted to home ground – the Puy de Dôme.

Stage 20 of the 1964 Tour was some 237km in length, but in reality, the day was mainly a long preamble towards the moment of truth awaiting the two protagonists atop the dormant volcano brooding over Clermont-Ferrand. The wait for the duel to commence only heightened the anticipation.

The Puy de Dôme is a short climb, just 6km in length, but the sheer relentless of its gradients means that time seems to slow down on that narrow and wickedly steep road. “The last kilometres seem to last as long as the whole stage,” Goddet wrote afterwards.

Time was of the essence for both men, with another time trial to come in Paris on the final day, and most observers reckoned that Poulidor needed at least half a minute or so over Anquetil ahead of that 27km test. In reality, maybe there was no need to overthink it: the jersey was the thing. If Poulidor managed to wrest the maillot jaune from Anquetil by any margin, the Tour was his to lose.

Such were the stakes when the climb began, with Anquetil and Poulidor immediately to the fore in a front group that also featured Julio Jimenez and Federico Bahamontes. The rest of the group began to melt away once Jimenez and Bahamontes began trading accelerations on the lower ramps of the ascent, and the Spanish duo would eventually forge clear. 3.5km from the summit, Anquetil and Poulidor were finally alone together.

Rather than defend himself by sitting on Poulidor’s wheel, as one would expect in modern cycling, Anquetil opted to place himself to his rival’s right-hand side. He was following the advice of Geminiani, who maintained that the psychological ploy was of greater benefit to Anquetil than the shelter of Poulidor’s wheel, and they would remain locked in those positions for more than two kilometres, pedalling side by side as they battled grimly against the gradient.

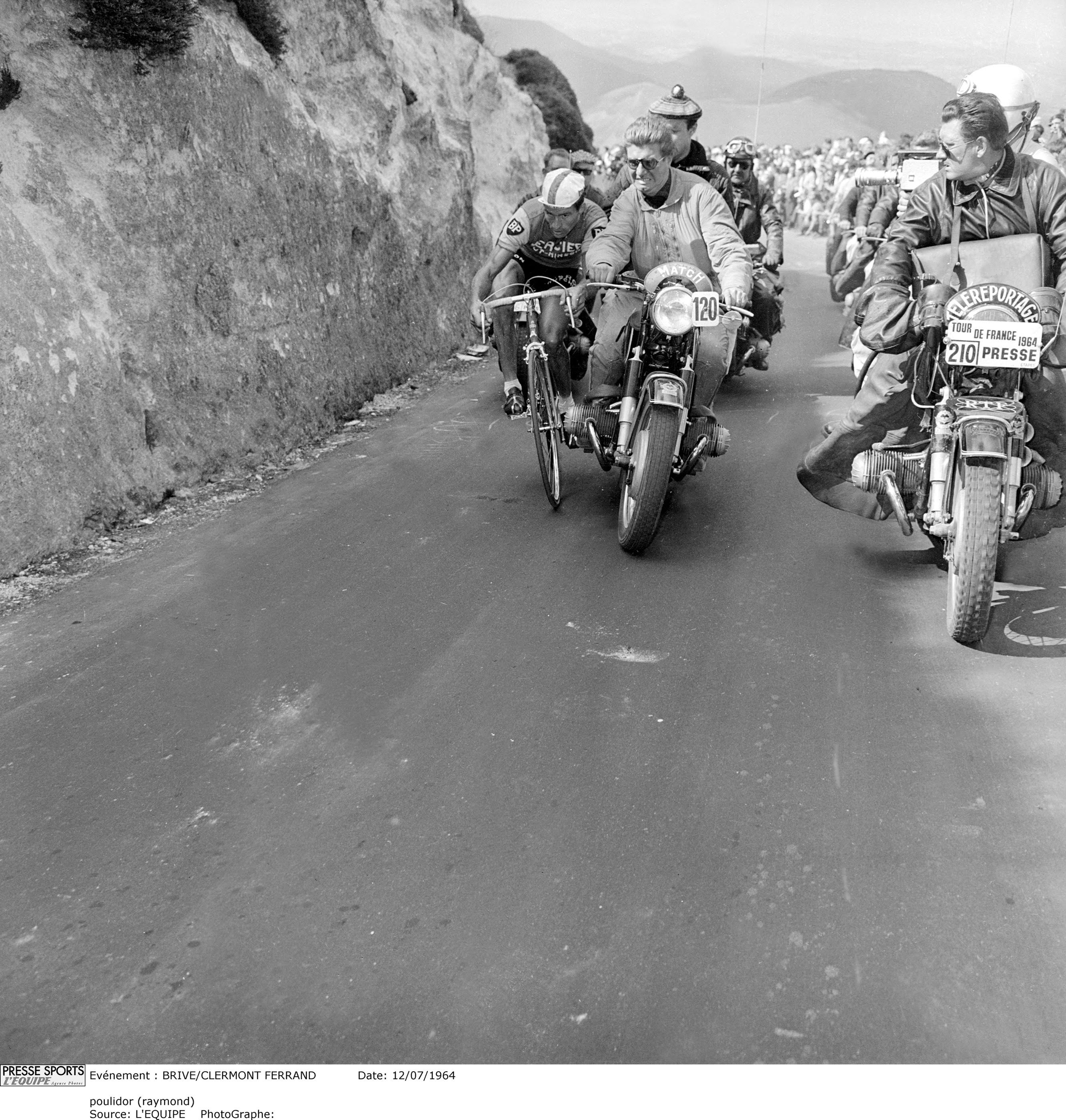

The crowds grew deeper as the climb drew on, while a flotilla of press motorbikes stalked them all the way, but each man seemed oblivious to everything but the ten metres of road in front of him and the rival at his elbow. 1,500m from the top, those elbows briefly came into contact, but still Anquetil and Poulidor stared ahead, as though each man believed acknowledging the other’s presence to be tantamount to a concession of defeat.

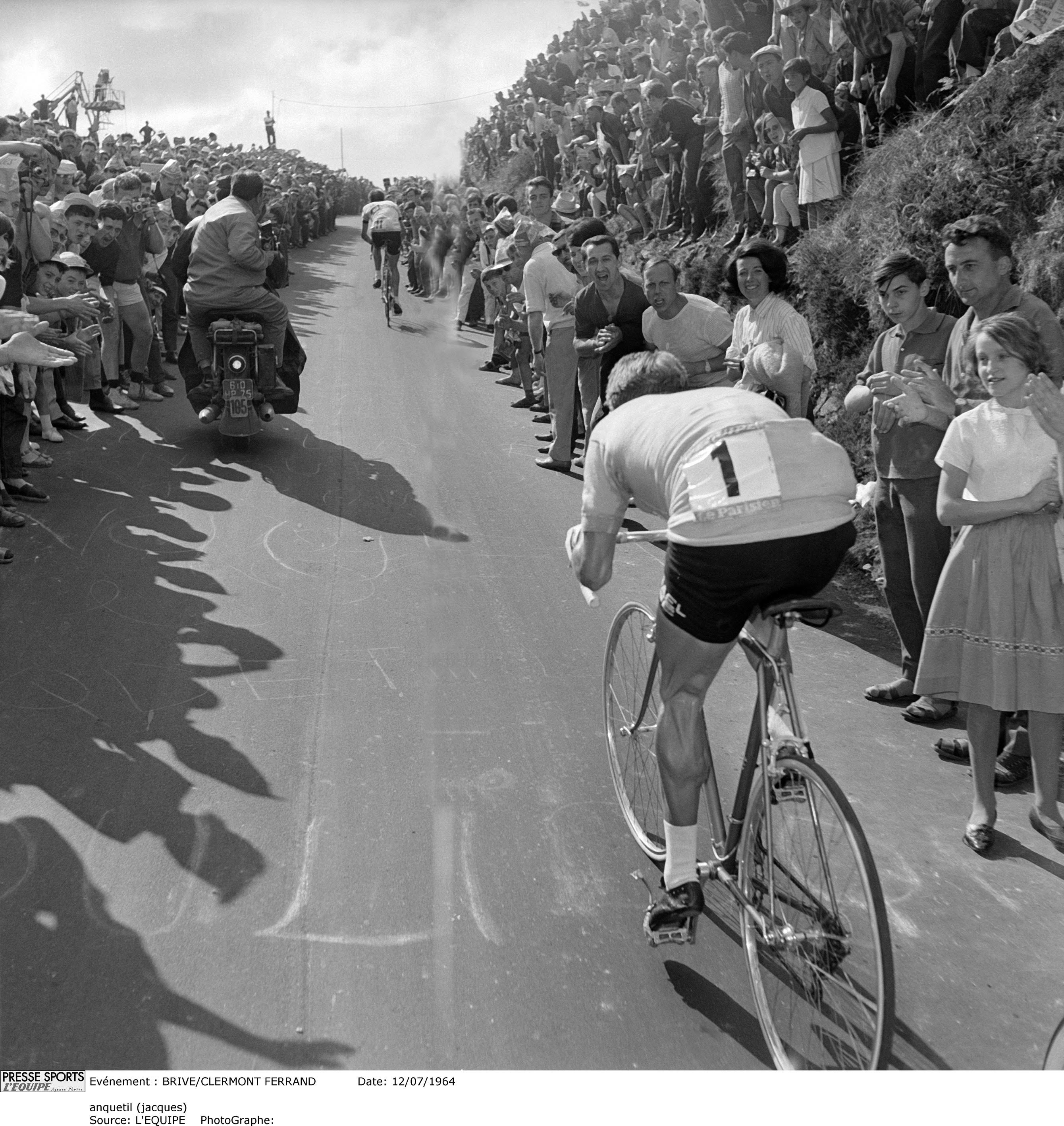

Shortly afterwards, however, Anquetil began to betray his first obvious signs of discomfort, as they approached the final kilometre, Poulidor began to ready himself for the attack. Poulidor’s acceleration finally came 900m from the top, and Anquetil could resist only for 50m or so before sitting heavily into his saddle and letting his rival go.

Anquetil’s pedalling slowed as he slumped over his handlebars during a final kilometre that seemed to last an eternity. Poulidor inched his way out of view, roared on by the multitudes who lined the upper reaches of the mountain. Anquetil, slowing further, was caught and passed by Vittorio Adorni. Poulidor crossed the line third on the stage, and then waited for the verdict of the mountain.

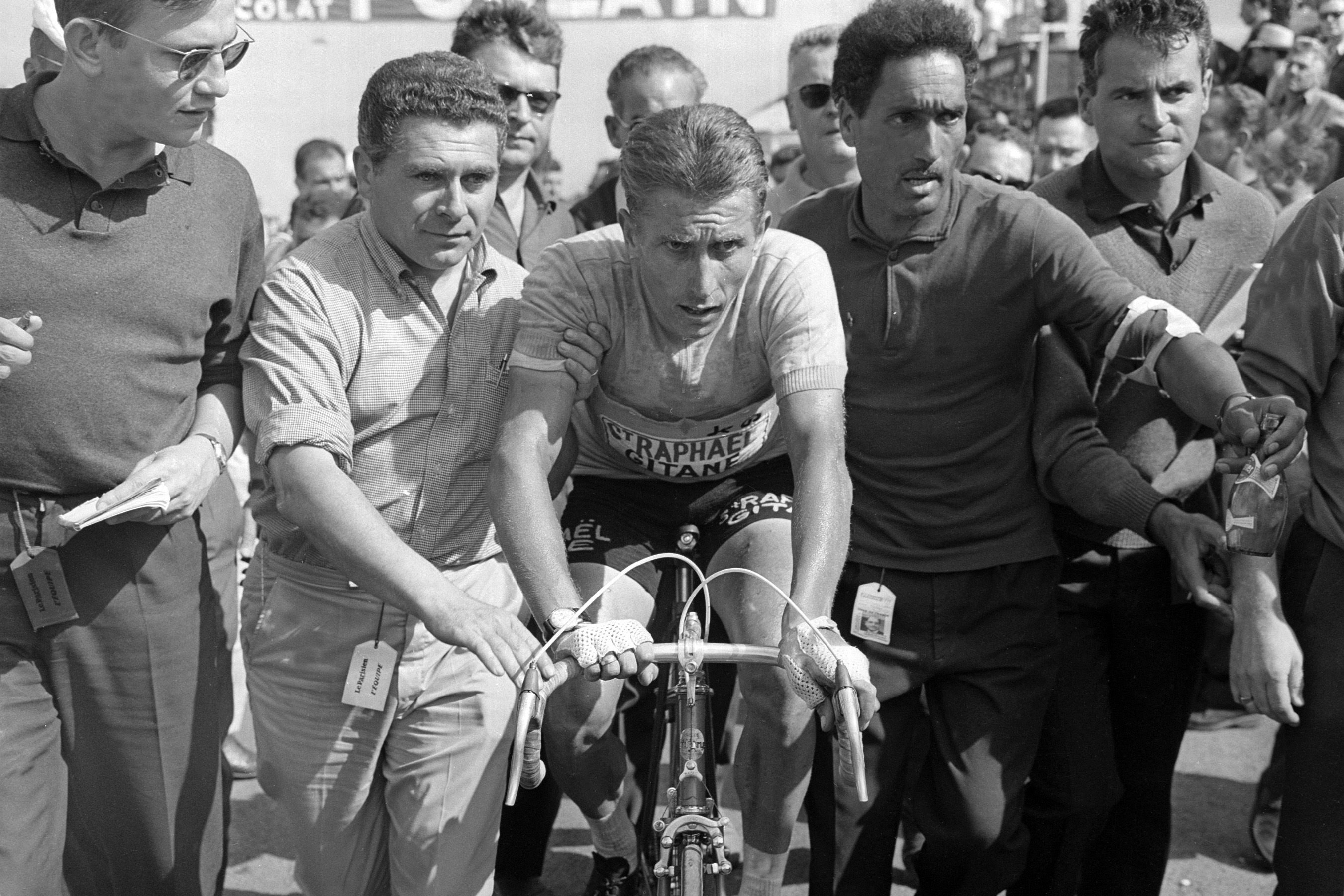

Some 42 seconds passed by the time Anquetil all but slumped across the line, his haunted eyes betraying the fact that he didn’t yet know his fate. When Geminani told Anquetil he had saved his maillot jaune by 14 seconds, his answer was succinct: “That’s 13 more than I needed.” The jersey was the thing.

The Tour was won. Even if the tightness of the margins and the extent of Anquetil’s collapse in the final 900m of Puy de Dôme gave some poulidoristes reason for hope in the final time trial, the man himself knew his chance had passed him by. “The Tour is over,” Poulidor said at the finish.

He was right. Anquetil, inevitably, sealed his fifth overall title in the concluding Bastille Day time trial, but the race of truth at this Tour had already taken place on Puy de Dôme. The tone of the post-mortem was set in the moments after Poulidor had finished, when three-time Tour winner Louison Bobet issued a gentle word of admonishment: “You went too late.”

Poulidor agreed, but only to a point. His attack came too late to win the Tour, true, but only because he wasn’t able to accelerate any sooner. “If I only dropped him 900m before the finish, it’s because I wasn’t able to do it before then,” he said later. “It’s easy to say I should have attacked earlier, but you don’t drop Anquetil just like that.”

That view was corroborated by Anquetil, who pointed out that both men were, by the time they reached Puy de Dôme, rinsed of all energy after a tumbling, spin cycle of a race where they had each flirted with disaster along the way. “The truth is that at Puy de Dôme, we didn’t see a great Poulidor or a great Anquetil,” he said. “The race had been very testing, physically and mentally. We were both tired.”

And yet, the idea took hold in the popular imagination that Poulidor had ultimately frittered away his chance of winning the Tour, spooked by Anquetil’s half-wheeling bluff. Poulidor, so that line of thinking went, had the legs to claim the yellow jersey that afternoon, only for Anquetil’s sangfroid to win the day.

Over the years, that notion has only heightened the mystique of that sweltering afternoon on the Puy de Dôme. It’s what draws people back again and again to look deep into that image for all the threads that made up the Tour’s greatest duel. Man against man. Man against mountain. Man against his own doubts. No wonder we can never look away.

What’s in a Cyclingnews subscription? We use our subscription fees to be able to keep producing all our usual great content as well as more premium pieces like this one. Find out more here

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.