Megan Fisher's Unbound Gravel message: 'We are all more capable than we know'

Decorated Paralympian returns to contest grueling 200 miles through Flint Hills of Kansas

Decorated para-cyclist Megan Fisher will be one of the hundreds of athletes taking the start line to contest Unbound Gravel in Emporia, Kansas. The dual American-Canadian citizen is a 10-time world champion, four-time Paralympic medallist and the first person with a physical impairment to finish in the 200-mile Kansas event in 2019.

She returns this year, not just to race, but with a message for those who doubt their ability to tackle something as notoriously challenging as Unbound Gravel 200.

"I say, 'you can do it.' If you want to do it, make a plan, and do it. We are all more capable than we know."

Fisher's story is one of pain and loss, hope, perseverance, determination, strength and inspiration. In 2002, 19 years old and a sophomore tennis player at the University of Montana, Fisher was involved in a horrific car accident while travelling from Chicago to Missoula, resulting in a brain injury and a lower-left leg amputation. Her best friend, Sara Jackson, died in the accident.

"Our car was full of everything, including our hopes and possibilities," Fisher says. "I think of Sara every day. I don’t know if there is an afterlife but I don’t want her loss to be a loss. I want there to be something good that came from all of what happened."

Fisher underwent two separate surgeries on her left leg, the first to remove her foot (below calcaneus) directly following the accident. The second, a revision surgery, happened a year later to remove her leg from below the knee (transtibial). She could no longer play tennis, but she returned to the courts determined, at first coaching players while seated in an office chair until doctors fitted her with a prosthesis.

Fisher says that she experienced many changes in her life following the accident. Learning to embrace her injuries and a new community was an essential part of her recovery.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"I grew up being athletic, and that's how I related to people, those were my friends, and that was my community. Having my abilities drawn into question was very hard. At first, I couldn't sit up on my own, and I had a hard time talking, I couldn't walk, and I was in a wheelchair," Fisher says.

"It also changed my friend group. Everyone went to college and left, and all of a sudden, I was still stuck at home with my mom helping me to the bathroom or making food for me. I was very dependent, and that transition was hard. I had to make new friends. I had a new, different personality because I had been shy, but now I'm not - frontal lobe injuries will do that to someone's personality.

"I have two chapters of my life. I went from being a tennis player to not knowing what or who I was anymore. What was I? A lot of people struggle with finding identity, and I didn't want to be disabled, nobody does, and so learning to embrace it and finding a community in that was important."

Perspective

During her recovery process while regaining independence, Fisher found her way into cycling. She says it was primarily thanks to her service dog Betsy, who joined her as a companion on long trail rides. "I blame all the good things on my dog," Fisher says.

"At one point, I was told that I would never walk again. I had a service dog named Betsy, 'The Wonder Dog'. She could do many things with me and for me, but she required me to get outside and play, too. I couldn't walk enough to make Betsy tired, and you can only throw a ball so many times. I saw people mountain biking with their dogs, and I thought maybe I could figure that out. She had a lot of energy and mountain biking was perfect for her, and we had a lot of trails around Montana."

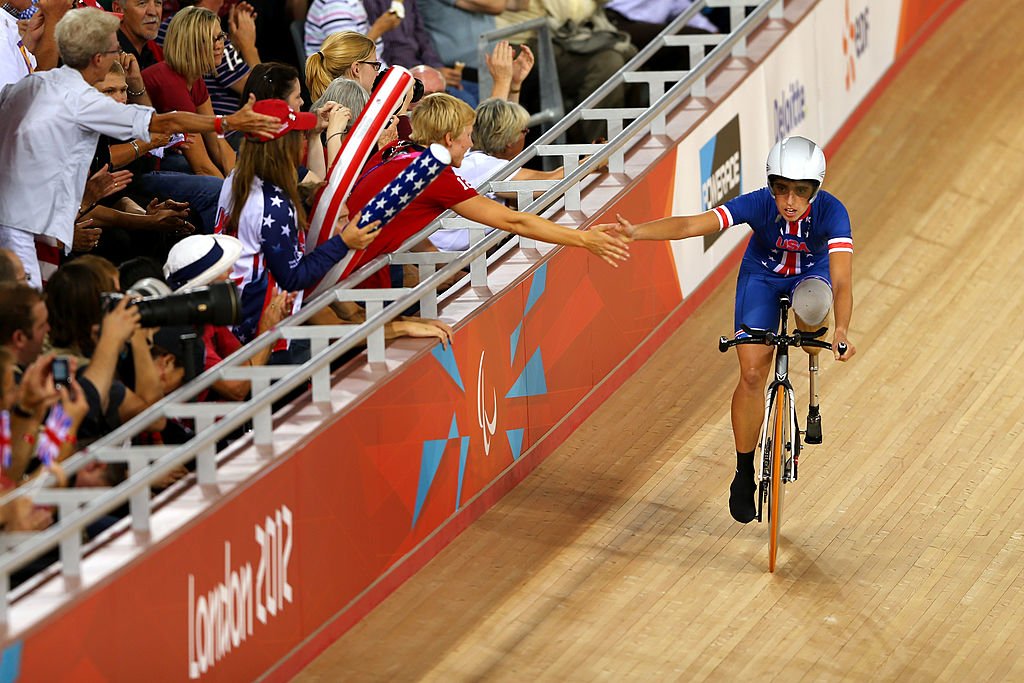

It wasn't long before Fisher entered her first triathlon in 2004, and she moved on to XTERRA triathlon in 2008 and then joined the Team USA para-cycling programme in 2010. In the two decades that followed the accident, she secured 10 world titles, gold and silver medals at the London 2012 Paralympics, and silver and bronze medals at the Rio 2016 Paralympic Games. She competed in the WC4 classification and specialised in the individual pursuit, road and time trial.

Fisher says that she idolised speed skater Bonnie Blair and tennis player Lindsay Davenport when she was a child. Still, she never expected to become a top-level athlete herself, nor to achieve so much success as a para-cyclist.

"No way, never. All of a sudden, you hit college, and you realise, 'Wow, I'm not as good as I thought I would be', and so you kind of let that ship sail. We all watch the Olympics and think how cool it would be to wear your nation's colours and hear your national anthem or represent your community and family," Fisher says.

"I didn't know this was a possibility for me. I didn't know my disability qualified me for the Paralympics because I didn't see that around me at first. Learning that it was OK to be disabled - we are all a little bit impaired, to be honest - but my impairment sits on a classifiable spectrum by the International Paralympic Committee.

"I speak as a physical therapist, too, when I say that nobody is perfect. Our lives are all about compensations and recoveries from injuries. At the time, I didn't know that I would ever get the chance to wear our nation's colours or to hear our national anthem.

"I can't believe it's been my life. Like many people, we tend to belittle our qualifications or downplay them and view them as being not that exceptional. I turned the corner on that because … it was a big deal."

Most importantly, Fisher says her sporting career helped her gain a new perspective on life and that she hopes people can relate to her story in the future.

"People reach out to me to say they look like me, and they see their journey reflected in my own," Fisher says. "We all have scars, and some people wear them more visibly than others, and so I can't hide mine, and I don't want to because I want people to be able to see their stories in mine. The human experience is more similar than it is different."

Never give up

Fisher retired from an exceptional career in para-cycling and has gone on to earn her Doctorate in Physical Therapy. She now works as a physical therapist for the Giant and Liv Co-Factory Off-Road Team. She also owns and operates a physical therapy, sports medicine, and coaching business in Montana, when she's not travelling with the athletes and team abroad to UCI Mountain Bike World Cups.

She is a lover of off-road racing and spends her free time training for long-distance gravel and mountain bike events - Unbound Gravel, LeadBoat Challenge, and Rebecca's Private Idaho Queen Stage Race.

She competed in Unbound Gravel two years ago, where she was the first person with a physical impairment to finish the 200-mile event. She covered the distance in 18 hours and 45 minutes. She pushed through the gravel and over the climbs while also stopping to help encourage other riders not to give up along the way.

"I never give up. I always have hope, for better or worse, and I don't give up on myself, and I don't give up on other people. It's a privilege to help motivate people out on the course, ride with people, be friendly, and give out snacks. Also, if a one-legged girl passes you, well, you can probably find another gear."

Fisher built her bike with a miss-matched crankset, 165mm on the left and 170mm on the right, and her custom prosthesis directly mounts to her left pedal.

"My prosthesis is specially made, and the cleat placement is, more like, underneath my heel or arch of my foot, and the pylon is a little bit longer so that I can reach the bottom of the pedal stroke. The left crank arm is shorter so that I don't have as much knee flexion at the top of the pedal stroke because too much flexion causes blisters behind the knee."

Fishers says that additional considerations include the pedal stroke and power output differences on each side. She also needs to be careful not to pull out of her prosthesis on the upstroke.

"Everyone gets sweaty. Your legs don't fall off when they get sweaty; mine does. I have to stop every so often to readjust my leg, but my foot never goes numb or swells, so I don't have to worry about that, but I would not say that it's an advantage," Fisher says.

"I ride with a power meter, and my left leg does not do as much work as my right leg. My right leg is about 70 per cent, and my left is about 30 per cent. If I pull up too much, then I pull myself out of my prosthesis. I can only push down, no sweep across the bottom, and very little pull up, no sweep across the top, either."

Training for long-distance gravel races involves spending a lot of time in the gym. Fisher explains that surgeons removed a section of her abdominal muscles following the accident to transplant it to another area of her body. She now needs to maintain her baseline strength and resiliency.

"I move differently through the world, we all do, we all have compensations. To do long stuff, I need to be strong, so I go to the gym," Fisher says.

Fisher says that it's in the challenges we choose for ourselves and the setbacks that we can't plan for when we realize our strength and resilience.

She will line up on the starting line at Unbound Gravel with the knowledge that no one ever arrives feeling 100 per cent prepared, not at a bike race, and likewise, not in life.

"We are never going to feel like we are ready, and yet we still succeed. Another day comes, and we try again. It's a lot harder to give up than it is to keep going," Fisher says.

"I want people to recognise the trauma, heartaches and setbacks that they overcome, and use my energy, strength or story to help them tackle whatever lies ahead."

Kirsten Frattini is the Deputy Editor of Cyclingnews, overseeing the global racing content plan.

Kirsten has a background in Kinesiology and Health Science. She has been involved in cycling from the community and grassroots level to professional cycling's biggest races, reporting on the WorldTour, Spring Classics, Tours de France, World Championships and Olympic Games.

She began her sports journalism career with Cyclingnews as a North American Correspondent in 2006. In 2018, Kirsten became Women's Editor – overseeing the content strategy, race coverage and growth of women's professional cycling – before becoming Deputy Editor in 2023.