Mechanical revolution

There's a sudden fashion in America for 'fixies' - bikes with no gears, no freewheel but just a...

Tales from the peloton, June 16, 2007

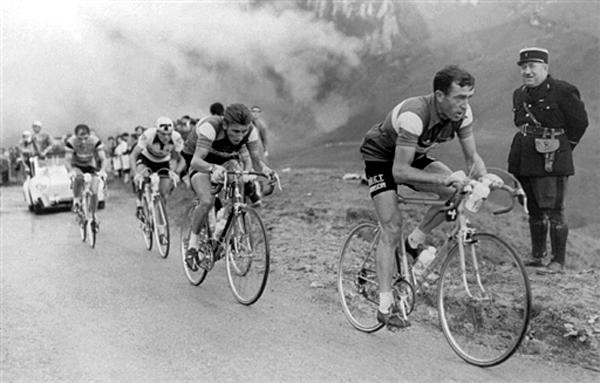

Who has what 'gear' is an important topic in the world of cycling. Les Woodland reflects on the important role the gear has played in the sport's history.

There's a sudden fashion in America for 'fixies' - bikes with no gears, no freewheel but just a direct connection between pedals and the back wheel. A track bike, in other words, but with brakes to make them legal. They were the talk of the Seattle bike show.

'Simpler is better' was the catch phrase there - although doubtless few who claim it would go back to the simplicity of solid tyres as well.

The time was, of course, when everyone rode a fixed wheel. Even after freewheels became available - a mechanism and a word given to the world by cycling - many enthusiasts believed there was a superiority both mechanical and athletic in riding a fixed wheel.

In Britain, where everything in cycling headed in the opposite direction from everywhere else, the sport pretty much limited itself to lone racing against the clock and organisers of early-season events often committed participants to ride on limited gears. Often the rule was imposed for the good of the riders, who in those days used to suffer from the now-vanished ailment of 'Easter knees'. The cycling journals of the 1950s were full of Easter knees.

You'd think the field would creep along, but it was nothing like that: the best could turn a 48 x 18 gear at 125rpm to finish a 25-mile race in less than an hour. To put that in context, and to show how things have developed in 50 years, Lance Armstrong averaged around 108 rpm in flat time-trials in the Tour, turning a gear half as big again (53 x 13).

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In France, and the rest of the European continent, riders hadn't raced on fixed wheel on the road almost from the day the freewheel was invented. It was the Tour de France that clung to rules insisting riders had single gears but that was the whimsy of Henri Desgrange, who disliked multiple gearing because, in his view, it detracted from a pure competition between legs and lungs.

When Antonin Magne won the first Tour de France individual time-trial in 1934, he therefore did it on a single gear of 49 x 16. With the ability to turn legs at that speed, it was pedalling speed rather than thigh strength that was seen as producing bike speed. Then gears were allowed in the Tour just before World War II and the speed leaped.

After the war, in 1952, another Frenchman, Louison Bobet, slammed his bike into 52 x 14 - pretty much the highest gear that machinery would provide - when he reached the wind-blown final stretch of the Grand Prix des Nations in 1952.

A blonde, 19 year-old whom few had heard of watched with interest as Bobet came from behind to take the podium, thanks to that gear. The next year Jacques Anquetil fitted a single 52-tooth chain ring and a one-step, five-speed freewheel that gave him 14-18.

If any one rider became associated with high gears, it was Anquetil. He made high gears look good. Unlike the others, he stayed in them all the time. Unlike everyone else, he could turn them with a silky smoothness that only the showers of sweat that he shed showed wasn't effortless.

The development shook the components industry. In the 1950s, the derailleur was still less than perfect. Lucien Juy of the French company, Simplex, had made the first modern derailleur in 1938, one on which the jockey wheel moved in and out and backwards and forwards, like a modern gear. But enter a speck of dirt in a vital place and it jammed. Nevertheless, Juy's design became standard in the Tour the moment the ban on derailleurs was lifted.

Simplex then lost ground to Campagnolo, whose gears worked better because Italian engineers thought to offset the pivot of the roller cage so that it could handle a wider range of gears.

Now all that stopped riders was the strength of their legs.

Roger Rivière used 53 x 13 to win a rolling time-trial in the Tour of 1959. By 1963, Raymond Poulidor was riding 53 x 13 - and winning.

Eventually British time-triallists caught up with abroad and they went still higher. Poulidor was one of the strongest riders in the world but quite ordinary British amateurs began to think a chainring three teeth larger was the least they could use. Where time-trials were won once at 125rpm, they were now topped by 56-tooth rings turned at just 80rpm.

Peter Valentine, a coach who devoted his life to a campaign for fast pedalling, used to complain that time-triallists used gears so high that they weren't so much pushing the pedals down as pushing themselves up from the saddle. Bizarrely, not until Freddy Maertens used 55 x 13 in 1976 did Continental professionals get anywhere near what British club riders were using on Sunday mornings.

The 11-sprocket is now here for those who can turn it - although, in the way these things never go in the same direction, the highest gears are available just as professionals have begun to learn the benefits of pedalling. Armstrong started it, out-accelerating Jan Ullrich and the rest of the world in the mountains of the Tour - and only the stupid didn't rethink their habits. If they had reached the limit of their speed by pushing, what were they to lose by trying once more to pedal?

The outcome, coincidental or not, is that speeds have got even higher. Somewhere in another world, Peter Valentine and the ghosts of the 1930s will be rubbing their hands and saying "We told you so!".