McKenzie's big day out: Linda McCartney at the 2000 Giro d'Italia

A look back at how the British team of vegetarians fared in their only Grand Tour

In 2020, Team Ineos stands at the top of professional cycling, a Grand Tour behemoth which has transformed British cycling since its creation in 2010.

Seven Tour de France titles, two editions of the Vuelta a España, and one at the Giro d'Italia have followed since. The latter race has provided the most complicated challenge for the team through the years.

Back in 2000 the Linda McCartney team was a far cry from the Team Ineos powerhouse that we know today. Burning brightly and extremely briefly, the British squad disappeared from the sport less than a year after making their Giro d'Italia debut, with a lack of sponsors and rising debts leading to the painful end of the team.

But the 2000 Giro d'Italia was the moment the team got to show what they could do on one of the biggest stages in cycling. They hit the zenith of their short existence.

Max Sciandri was Linda McCartney's best finisher in the Vatican prologue with 30th, but things improved as the race as the race headed south, before reaching Basilicata and then moving north up the Adriatic coast into the second week.

New recruit Sciandri was among the most experienced members of that team, the then 33-year-old having enjoyed spells at Motorola and FDJ in the 90s, winning stages at the Giro, Dauphiné and Tour de France along the way.

The other major name on the squad was another new addition, Pascal Richard – the 1996 Olympic gold winner and four-time Giro stage winner – in what would be his last year as a professional. Ex-Amore e Vita rider Maurizio De Pasquale was the lone Italian, while Matt Stephens, Tayeb Braikia, Bjørnar Vestøl, Ciarán Power, Ben Brooks and David McKenzie rounded out the team.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Richard and Brooks quickly left the race though, forced out after coming down with a virus after the opening day.

After that rocky start, the results improved throughout the opening week. The Dane Braikia acquitted himself well with an eighth-place sprint finish in Terracina on stage 1, while another sprint on stage 3 saw Power grab a top five finish, and then Braikia made the top ten once again on stage 4.

Stephens, meanwhile, was fighting on after a crash on stage 2 saw him finish alone and outside the time cut before receiving a reprieve from the race jury. He eventually made it through several days in the mountains and to stage 15 to Brescia before withdrawing due to a chest infection.

Through the opening week and the first British team at the Giro appeared like a typical case of plucky Brits abroad – even if only two of the nine-man squad were British. The team management had little Grand Tour experience and it showed day after day.

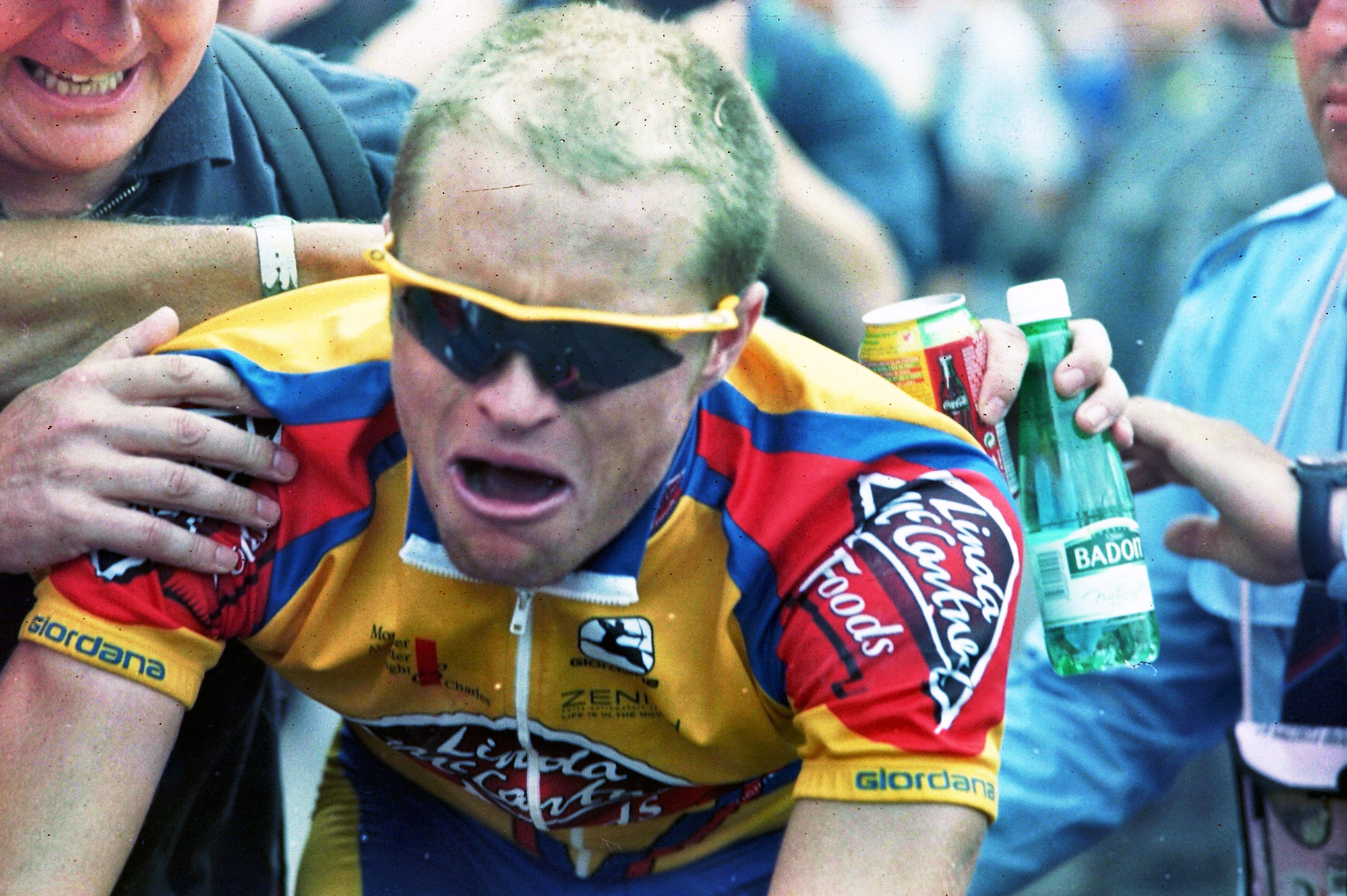

David McKenzie's solo ride

But stage 7 changed all that, the rolling 182km stage in Abruzzo, hugging the Adriatic en route from Vasto to Teramo and offering a chance of breakaway success.

After 15km of attacks flying to make the breakaway, it was Australian David McKenzie who managed to escape the grasp of the peloton and get away. The 25-year-old had won several stages of the Herald Sun Tour in the 90s, racing for home squad Giant-AIS as well as Italian team Kross-Selle Italia before moving to Linda McCartney in 1999. The Giro d'Italia was his first and only shot at the big time.

"The first six days of the Giro, I just felt like I was riding alone in the bunch, getting dropped on the last climb, making the gruppetto," McKenzie told Cyclingnews a year later.

"I thought to myself, I can go another two weeks of this and just be another statistic in the Giro, or I can at least have a go. Instead of watching attacks go up the road, I can be the first guy to attack and maybe start something, at least put myself out there, give myself a chance. That's basically what I did."

McKenzie was over just 50 minutes behind the race leader Matteo Tosatto when he set out on his lonely voyage up Italy's east coast. As a result, there was little resistance to his solo raid. Well, raid would have been a euphemistic term for what is usually a mission of no-hope with almost 160km of rolling roads left to cover.

"It was just one of those days," McKenzie said. "I don't think you get them very often in cycling anymore – everything is so competitive. But there's always one day in Grand Tours where one rider attacks and they just let him go and he slowly builds up a lead.

"Everyone was just happy to ride along for the next three hours. That's when I thought: 'this is it! This is my opportunity to do it!' I wasn't real interested in going on my own, but once I got over two minutes, I knew it was going to be a long day."

McKenzie built up a 12-minute advantage out front, riding with just the television motorbike and commissaire's car for company, plus veteran directeur sportif Keith Lambert in the Linda McCartney team car. Team Polti's Eddy Mazzoleni rode alone minutes down the road, attempting in vain to make it across.

"At the time, I thought [12 minutes] was nowhere near enough," remembered McKenzie. "I remembered watching the Tour on TV and seeing guys build 20 minutes and still get caught. So, I just said, well at least I'll make a name for myself - give the team a bit of publicity anyway."

In fact, the Australian didn't think about the possibility of actually winning the stage until well into the day, over three-quarters of the way into the stage.

"I guess it wasn't until the last 40km that I started to believe I could do it," he said. "Then I thought that it's only an hour – if I ride fast enough! All sorts of things were going through my mind."

The kilometres – and the time gap – ticked down as McKenzie pushed on. With 60km to race he had four minutes on Mazzoleni, with 20km to run it was 2:20. The peloton passed the 10km banner at 3:30.

The danger from the peloton was over by then, and Mazzoleni was only a minute up on them, too. Only a stroke of awful luck would stop a glorious debut Grand Tour for the British squad.

Ivan Quaranta's Mobilvetta team had taken up the chase behind, aiming for another stage win to go with his victory in Terracina six days before, but it was too little, too late – McKenzie had done it.

"As the gap started to come down and down, I kept thinking I was going to be caught in the last kilometre," said McKenzie. "I was thinking - oh well, at least people will be sympathetic towards me, but in the end it never happened.

"Even though it was only fifty seconds in the end, I got there easily in a way. I mean, you see guys win by 10 metres or less, so it was good to be able to sit up and enjoy it in the last kilometre."

Celebrating on the run-in to the line, McKenzie was quickly joined by ecstatic staff members, including PR man John Deering, who was jumping around wildly as the Australian sealed victory.

The plucky underdogs had gone to Italy and managed to grab a stage win in the unlikeliest of fashions.

"The critics said we'd never get a start in the Giro, that we'd never finish if we did," said McKenzie. "I guess people were going off the record of the ANC team in the 1987 Tour. Obviously, we all wanted to prove them wrong.

"Personally, I was proud to be part of the McCartney team. For us it was huge success. We went there with the goal of winning a stage and for me, it was a dream come true. In the back of your head you dream about it, but you don't actually tell anyone what you want to do, until it happens!"

McKenzie's miracle ride wasn't to be repeated for the remainder of the Giro, though Sciandri came the closest the very next day. The team leader took second on a tough, hilly stage to Prato, mixing it up with Filippo Casagrande and a young Danilo Di Luca on the final climb of the day.

Sciandri came across to the lead group on the descent to the flat finish in the town, but lost out to Mapei's Axel Merckx, the Belgian attacking late on straight after re-joining the lead group. Sciandri won the sprint for second just six seconds later.

Ciarán Power and Tayeb Braikia nabbed a few top-ten placings on the way to the race finish in Milan, too, but from then on it was downhill for the team, despite a Sciandri win at the Giro del Lazio in September.

The budget for the 2000 season had run out by the summer, with team owner Julian Clarke receiving an advance on the 2001 payments from main sponsor, Linda McCartney Foods.

The team somehow got through the 2001 Tour Down Under, with fake sponsors and broken promises keeping the dream and the team alive. McKenzie won the final stage but soon afterwards, it was all over. New sponsors Jaguar and Jacob's Creek may have been on the jerseys but were not actually paying anything – and in the case of the car manufacturer, had only held talks about possible sponsorship.

For the 2001 season, title sponsor Linda McCartney was simply a name and logo rather than a source of funds, too. By the end of January, the team was kaput, with anywhere between hundreds of thousands to millions of pounds missing.

In the end, the team was a castle built on sand. The brief dream of a top-level British squad flourishing in modern cycling began to unravel shortly after its peak.

Unlike Team Sky, Linda McCartney might not have won any pink jerseys or stepped on the podium in Milan, but the will be remembered in Italy for nailing the epic solo ride and winning a stage at the Giro d'Italia.

Dani Ostanek is Senior News Writer at Cyclingnews, having joined in 2017 as a freelance contributor and later being hired full-time. Before joining the team, she had written for numerous major publications in the cycling world, including CyclingWeekly and Rouleur. She writes and edits at Cyclingnews as well as running newsletter, social media, and how to watch campaigns.

Dani has reported from the world's top races, including the Tour de France, Road World Championships, and the spring Classics. She has interviewed many of the sport's biggest stars, including Mathieu van der Poel, Demi Vollering, and Remco Evenepoel, and her favourite races are the Giro d'Italia, Strade Bianche and Paris-Roubaix.

Season highlights from 2024 include reporting from Paris-Roubaix – 'Unless I'm in an ambulance, I'm finishing this race' – Cyrus Monk, the last man home at Paris-Roubaix – and the Tour de France – 'Disbelief', gratitude, and family – Mark Cavendish celebrates a record-breaking Tour de France sprint win.