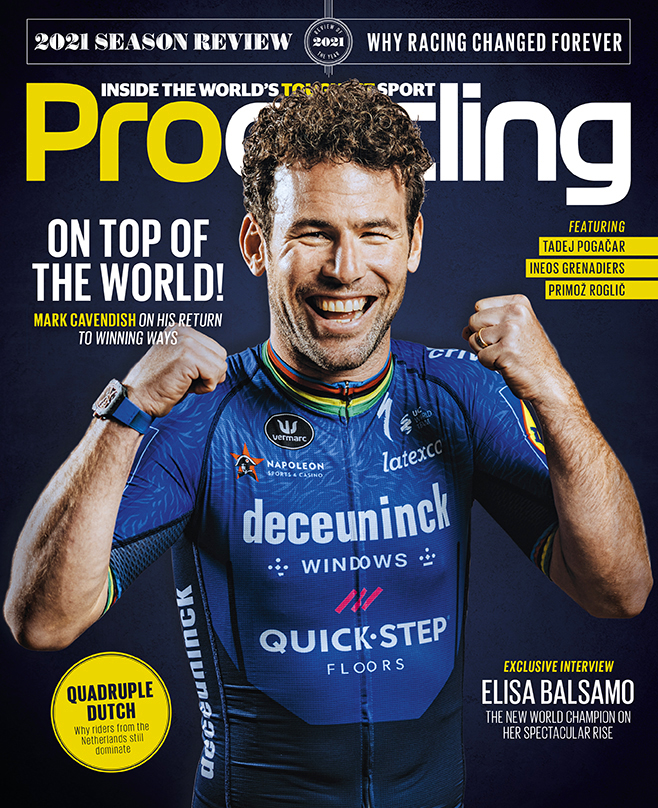

Mark Cavendish: The fire within

In an interview with Procycling, the sprinter explains how he returned to winning ways in 2021

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Everybody assumed Mark Cavendish was finished as a top-level sprinter after four very difficult seasons. Everybody, that is, except Cavendish himself. His extraordinary comeback to win four Tour de France stages was one of the defining stories of 2021. He tells Procycling how he did it.

Most, if not all cycling fans must have watched the steady cooling of Mark Cavendish's sprinting career over the last four or five seasons and concluded that the days of Tour de France stage wins were long gone. Cavendish has famously never been a 'numbers' guy, which is just as well for him, because the numbers told the story starkly: one win in 2017; one in 2018; none in 2019 and 2020.

Even if the data weren't the whole story, there was plenty of circumstantial evidence that the process was also misfiring. Cavendish was pulling up well before the sprints properly started in the 2018 Tour, his Dimension Data team didn't even take him to the race in 2019, and 2020 was a write-off. The younger Cavendish fizzed and burned with energy, while the careworn thirty-something of the reluctant post-race postmortem through the late 2010s looked beat. Quantitatively and qualitatively, his career looked over. The fire appeared to have been extinguished.

However, any firefighter will tell you that smouldering embers can suddenly reignite and cause another blaze. While the rest of us were raking over the ashes and thinking back to the white-hot intensity of Cavendish's earlier career, Cavendish himself was about to start another fire.

It would be easy to say that Cavendish's unlikely journey through 2021 was a case of stars aligning, or steps, each leading to the next. He leveraged his heft as a previous star of the sport to bring a sponsor to Deceuninck-Quick Step and sign for the team. He got up and running, coming second to Tim Merlier at the GP Monseré in March, a result that looks better now than it did at the time. Second in a stage of Coppi e Bartali. Third in Scheldeprijs.

Then came the wins at the Tour of Turkey. A win at the Tour of Belgium. He was on an upward trajectory, with results in small races, then wins in small races, then a win in bigger races. We started drawing a line from where he'd been to where he was. If you projected forward, you could make a good case for predicting that next would come a result in a grand tour. And there was only one step higher than that.

At the same time, Sam Bennett, QuickStep's most successful sprinter of 2020, got injured, and fell out with the team's management. To paraphrase Ernest Hemingway, events happen in two ways: gradually, then suddenly. It was only late June when it was announced Cavendish would go to the Tour; within a couple of weeks, he'd won four stages.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Cavendish, who sees the world differently from most people in almost every instance, also sees this differently. We fetishise process a lot in cycling and life, and process played a big part in the Manx rider's success this year, but he also describes his trajectory through 2021 thus: "Imagine there's a path, with a wall at the end. I was riding full speed at it, hoping a door would open. As a pro, that's all I had to do, and ultimately as a pro, it's my job to be in good condition in case of that scenario. But on an emotional level, I just hoped the door would open. It would either open up," he concludes, "Or I'd bang my head."

'I can do my job'

Clearly, Mark Cavendish was the sprinter of 2021. The waters get a bit more muddied if you look at it more subjectively – you could argue that the opposition at the 2021 Tour was weak, comparatively. Bennett was out of form and out of favour with Patrick Lefevere, Caleb Ewan crashed out on stage 3, Dylan Groenewegen was a DNS.

Of the rest, Arnaud Démare was not at his best and the principal opposition was the ProConti duo of Jasper Philipsen and Merlier. But the evidence still supports Cavendish's case – four Tour stage wins is four Tour stage wins, and Philipsen and Merlier are no slouches.

There were also the facts that Cavendish has never stopped believing in himself and is the greatest sprinter ever. In an interview with The Cycling Podcast in late 2020, he pushed back against the evidence that suggested he was finished. People were looking at the results, he insisted, but not at the reasons. There was the long struggle with Epstein Barr. He was facing mental health issues. He wasn't aligned with his teams, both at Dimension Data and Bahrain. He wasn't on the right bike. Sort all those problems, he said, and he knew he was as good as he ever was.

What people didn't realise as they assumed he'd been given a place on QuickStep for old times' sake, was that he'd sorted all these issues: "At the start of the year, I knew," he says. "If I could have gambled, I would have gambled on me winning this year.

"I was on a bike that fitted me. That's fundamental. That was the start. I was thinking, 'I can do my job.'

"I was in an environment I loved being in last time," he continues. "With that formula I know I've got the best opportunity to win. And I know from the past that when I have the best opportunity, I can convert that."

Bike racers are good at racing bikes for all kinds of reasons. Some are physically gifted and rely on their strength, or their cardiovascular efficiency or their recovery. Some mitigate for deficiencies in any of these areas by working hard. Some work clever – knowing how to save energy, read people and understand race strategies goes a long way. Cavendish, despite the early propaganda saying his physical gifts were the least of his assets, is strong in all these areas.

But beyond even all that, the most remarkable thing about him is his self-belief, which may be the foundation of everything he has achieved. He used to express his self-belief a little less subtly and much more naively than he does these days, and people used to find him cocky, but I think it is the central, most pure expression of what makes Mark Cavendish Mark Cavendish. If you're looking for the glowing ember that reignited his winning career, it is that.

For most people, four years' worth of beatings at bike races would be enough to extinguish any remaining ambition, but it barely touched Cavendish. He was losing races. He was disappointed. He was frustrated. But he still believed. Even when one of the central figures in his career, Rod Ellingworth, his coach at the BC Academy, Team Sky and latterly his manager at Bahrain, wobbled.

"Nobody believed me, did they?" he says now. "But that didn't affect my belief in myself. Like, the public, if they believe or not, it doesn't affect me. The hardest thing emotionally was when Rod stopped believing in me. I think that was the only one emotionally that really really hurt."

Cavendish won't go into details about Ellingworth. When pressed, he only shrugs and repeats, "You can't change someone else's belief in your ability."

The Tour of Turkey

The penny dropped at different points in the year for everybody, regarding when they realised Cavendish was back in Tour stage winning form. For many, it wasn't until he actually won in Fougères on stage 4. Some might have looked at the four stages he won at the Tour of Turkey and realised that something special was brewing.

For Cavendish himself, it came with a disappointing-looking fourth place on stage 1 in Turkey. Fans might have watched the sprint, looked at the results, seen that he was beaten by Arvid de Klein, Kristoffer Halvorsen and Pierre Barbier, a distinctly C-List hierarchy of sprinters, and concluded that 2021 would pass much as the previous four seasons had. But that day was when Cavendish knew he was going to win races.

"That sprint was one of my best of the week," he says. "From that moment I had no questions at all. I'd had some results earlier in the year and was happy with how I'd been sprinting. But in Turkey, that's when I knew I could win at the highest level. Not just winning bike races, but at the highest level.

"I know Turkey's not the highest level but remember Jasper Philipsen was the most consistent sprinter of the year. He's a fucking good bike rider, that kid. André [Greipel] was there and he's not shabby. It wasn't the Tour de France, but it doesn't matter who's there. You know from how you are sprinting, well, I do, if I can be competitive and at what level. I knew there that I couldn't just win bike races, but I could take scalps.

"I took that confidence from the first day to the second day. Even when the gap opened on the second day, I stayed calm, used André to move up, went round him, didn't panic and I knew I could do it. Before, I didn't know I could do it and that's when you hesitate."

At the Tour of Turkey, it was clear Cavendish was back. At the Tour, that became unarguable. For the man himself, it was simply a case of the natural and proper order of things being put back in place.

"This has not come from nowhere," he says. "It's been dogged persistence. A lot of people talked about the stars aligning, but finding a sponsor, taking minimum wage, coming to a team you know you're going to perform at, that's not stars aligning, that's you putting things where you want.

"Things started to go out of place, and unfortunately there were people who kept putting them further out of place. I was trying to frantically get everything back together while continuing to ride my bike. Fortunately, I managed to get it back together how I liked it.

"But you've got to remember, I've been on my bike, competing at the highest level since I was a junior. I turned 18 and was world champion the year after. I did the Tour in my first year, the Giro and Tour in my second year, the Giro and Tour in my third year. What you get from that has an effect on your career later.

"So, when I started to build up again, I had a base I didn't have when I was younger. Am I the same rider as 2011? No. But with all respect I don't need to be, to win. I won by so far in those days, I don't need to do that."

It's the only time in the interview he sounds like he did in 2011, as well. Cavendish has more ownership of his unique psychology than he did in his early 20s, a point which he illustrates by talking about the relationship he has quickly built with his new coach, Vasilis Anastopoulos.

"We spent the last year working on basics, just being fit, and now we're working on training to sprint, rather than training to arrive at a sprint. But the feedback from Vasilis... I love it. He's doing every pedal rev with me. He's invested, so passionate. Fuck, I wish I'd met him 10 years ago."

He pauses and adds ruefully: "I said that to Patrick [Lefevere], and he said, 'If you'd met him 10 years ago you wouldn't have listened to him.' It's a good point. But I wish I had. He gets so much out of me."

Cavendish sums up how he perceives the last few years and how he started winning again when he lined things up: "I was trying to catch fish with holes in my net."

Winning at the Tour

We'll begin with the stage that Cavendish didn't win. Number 35 in Paris was the one that got away. Perhaps it was fatigue from a long Tour, or maybe the other teams had just had enough of being bossed around by QuickStep, but the Belgian team was swamped at a bad moment in the last two kilometres, and Cavendish never really recovered. He fought his way back to the front but started the Champs-Elysées in a box and never left it. Wout van Aert won, and Cavendish barely sprinted, though he came third.

"I ran over it in my head a lot," he says. "And we're not talking for hours. It was days, weeks…"

Cavendish's perception is that Philipsen's leadout man Jonas Rickaert deliberately boxed him in. It ensured Cavendish lost (and also, to Cavendish's mind, also ensured defeat for Philipsen).

"I've come to the conclusion that there was nothing I could do. If somebody comes in to make you lose, you can't factor that in. I don't regret it because there's nothing I could have done."

But Cavendish's primary memories of the Tour are the stage wins, numbers 31 through 34, which put him equal with Eddy Merckx as the all-time record holder. Not that he's any more willing than he was in July to compare.

"It's… back to normal. Maybe that's the wrong phrase, but what I used to do was win," he says. "I knew we had the best chance of anyone. With the team and leadout we had, the condition I was in, I had the best opportunity of anyone. It doesn't necessarily mean you win, but I knew there'd have to be someone better. I had the best tools to try and succeed.

"I think about the Tour a lot," he continues. "Always have, always will. It was just nice to be back, whether I won one or 21 stages. Of course, I'm excited to have won 34 stages, but that's because I've won 34 times, not because somebody else has or hasn't won that many. I really care that I've won 34. But I'd care if I'd won 20. I know more than anybody else how fucking hard it is to win a Tour stage."

Mark Cavendish thinks and looks back to the summer of his extraordinary resurgence, one of the great sporting comebacks of all time, and to the first of his four stage wins, and for a moment, he is back in Fougères.

"If I close my eyes," he says, "I can see the big red Vittel banner over the finish line coming. It gets closer, and nobody comes past. The most incredible feeling."