Mark Cavendish: Indian Summer

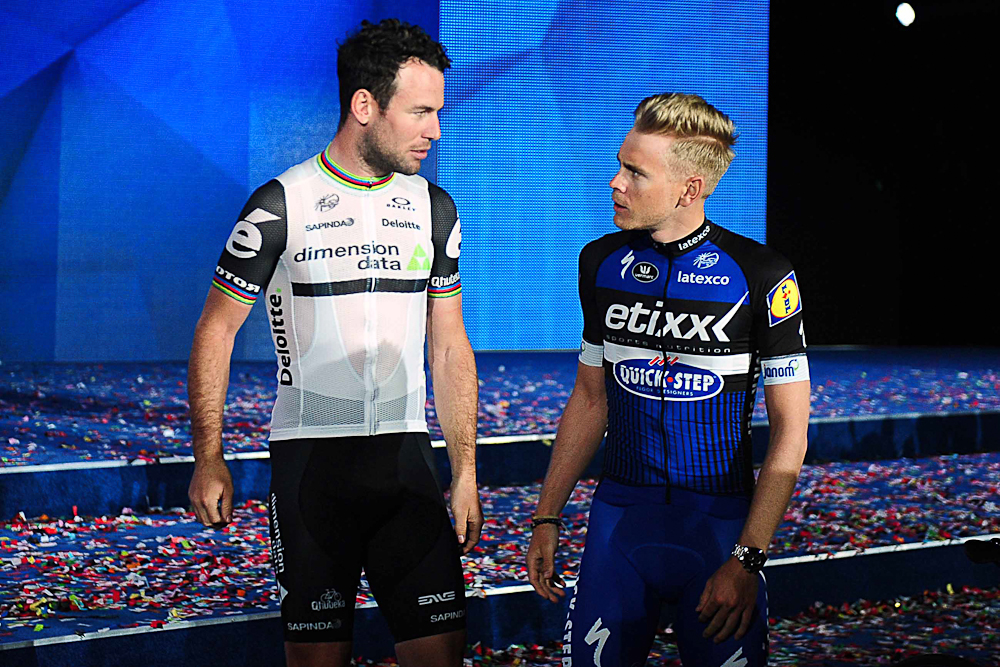

Mark Cavendish’s 10th full season as a pro is unlikely to alter his legacy.

This feature first appeared in Procycling magazine. To subscribe, click here.

Procycling’s Daniel Friebe, who knows Cavendish well, thinks it will tell us what’s left to gain for the Manx Missile.

After the breakthrough, beyond the rise and over the peak – but just before the point where twilight begins to cast its shade – there comes a moment in a sportsman’s life where thoughts begin to turn to the closing remarks.

Mark Cavendish turned 30 last May. For most professional bike riders, these are the salad days but, ever the realist, Cavendish is fully aware that the shadows on his monumental achievements have started to lengthen. When he said two years ago that the second half of his career may well be less successful than the first, it seemed an unduly bold statement. Today the same prophecy is an unfolding body of evidence, as it is for most precocious sports stars. Cavendish hasn’t needed blondes or knee injuries to fall victim to what might henceforth be known as “Tiger Woods Syndrome”; like Woods, he won too much, too young, to tee up anything other than an inevitable anticlimax in the end.

The truth is that crashing out of the 2014 Tour de France on the first day in Harrogate may have been the watershed and epiphany that Cavendish suggested at the time, though not necessarily in the way that he had hoped or expected. One of his oldest allies and mentors, the Danish directeur sportif, Brian Holm, said at the time, without malice, that it would serve him well to realise that, “this bike race and professional cycling can carry on without him, that he is not the centre of the world.” The previous January, coincidentally, Tony Martin had foretold the same kind of serendipity, if not the unfortunate way that it came about. When Cavendish turned to Martin on a training ride and admitted that he was tired – of the yearly grind, the relentless pressure, the travel, of having to win five Tour stages just to persuade the world he wasn’t washed up – his German team-mate suggested that perhaps he needed to sit out a Tour just to appreciate how much that race, and his job in general, meant to him.

When fate duly conspired to take him out of the Grande Boucle in sight of the first finishing line, Cavendish waited for a lightbulb to flicker. He thought this bitter experience would make him more hungry and, in a way, he was right; proof could be seen in the way that he defied initial prognoses to race again that season and even win twice at the Tour du Poitou Charentes. But it wasn’t his appetite for victories that had been revived; what had rebounded with a vengeance, as Tony Martin had suspected it would, was the pure love of being a professional cyclist, and his desire to stay in that trade for as long as his legs would allow. This is what Cavendish now tells friends, family and peers: he only wants to train, race and be part of a successful team. Ask him now whether he is mainly chasing records, recognition or the dreams that his long-time coach, Rod Ellingworth, always told him to follow, and he responds with a blank look: he simply doesn’t know, or hasn’t dwelled on the matter enough to formulate a reply.

The question that doubters may ask is whether the evasiveness isn’t also a shield or, worse, a cop-out. Just as Cavendish wowed a generation of fans with his slingshot accelerations – a motion picture that belongs in the professional cycling canon alongside a Pantani uphill attack or a Merckx victory salute – then so could the rawness of his ambition shock them. Him of all people saying now that really accolades don’t matter, nor being the best, and that he’s just still there for the sheer fun of it, surely stretches the bounds of credulity. Doesn’t it?

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Sceptics would be right in the sense that Cavendish does still care deeply about outcomes. He is still volatile. Part of him still can’t quite fathom why rivals get sympathy for their illness and injuries, whereas his have been brandished as evidence of terminal decline. He hasn’t yet understood why the others receive such acclaim for lacklustre seasons redeemed by one royal flush. Or, for that matter, how he can raise his arms 44 times in the three years he spent at his last team and still be deemed a flop. “Ach, f*ck ’em,” he’d say, either to himself or aloud. Which, again, some would argue, sounds a bit too much like faux nonchalance, feigning indifference when in fact it stings his every fibre to see André Greipel win four stages at the 2015 Tour, just as Marcel Kittel’s four victories the previous year burned.

Perhaps only Cavendish sees the complete picture. But what we can say without any fear of contradiction is that time has changed him. Defeats once ate him alive not only because his relationship with cycling was so visceral, so entangled in complicated emotions, but also because they were so rare. Now, marriage, kids, age and experience have phased in some perspective, and the losses are also a far more common occurrence. In 2009, Cavendish was beaten – truly outsprinted, not outmaneuvered – just twice in an entire year, at Tirreno-Adriatico and at the Giro; in 2015, it happened nine times. Quite simply, he has learned over time that losing is a part of life. Like it is for all of us.

He perhaps surmised his evolution best in an interview for Rouleur in 2014 with Edward Pickering: “I don’t understand my logic before. I really don’t understand what the f*ck was so important before. Who was I winning for? Who was I trying to impress? I can’t even remember or think what it was all for. It had to be for something. Did I want material gain? I don’t know. I have no idea what my drive was.”

So, no, never again will a sprint seem like a matter of life and death. For this reason – and not only because he has completed the transition from young upstart to establishment figure – it is rarer nowadays to hear other sprinters blaming Cavendish for causing danger or crashes. Similarly, in interviews, he is more likely to mumble platitudes than throw poisoned darts; again, there are more important things in life than telling the world they’ve got it all wrong, even if they have. There are better and more valuable uses of his energy.

What all of this means for the remainder of Cavendish’s career is anyone’s guess. Ellingworth still thinks that the racer’s instinct, suppressed for years, but which made a cameo reappearance at last year’s British National Championship road race, could be the spark for an Indian summer. At the very least, the alpha impulses that have challenged many a directeur sportif, team-mate and mechanic over the years, but also contributed hugely to the collective success of every one of his teams, make him ideally suited to the role of tutoring young riders and inspiring a still fledgling team such as Dimension Data. That is, if it’s a responsibility that Cavendish truly wants.

This article appears in the current edition of Procycling magazine, February 2016. To read Procycling’s in-depth and exclusive interview with Mark Cavendish, which runs alongside this feature, buy the magazine, which is available in UK newsagents now, and click here to Subscribe.