Marco Pantani's Giro d'Italia fall from grace at Madonna di Campiglio

A look back to 1999 and the missed chance to make a change

The following feature concludes our ‘I love the 1990s’ series, as Stephen Farrand recalls Marco Pantani’s dramatic expulsion from the 1999 Giro d’Italia. It was the culmination of cycling’s era of excess, but it was also a missed opportunity. Pantani responded with denial, repeated again and again until his tragically premature death in 2004. His entourage responded with a silence that endures to this day. Two months later, Lance Armstrong dominated the Tour de France, and the cycle began all over again.

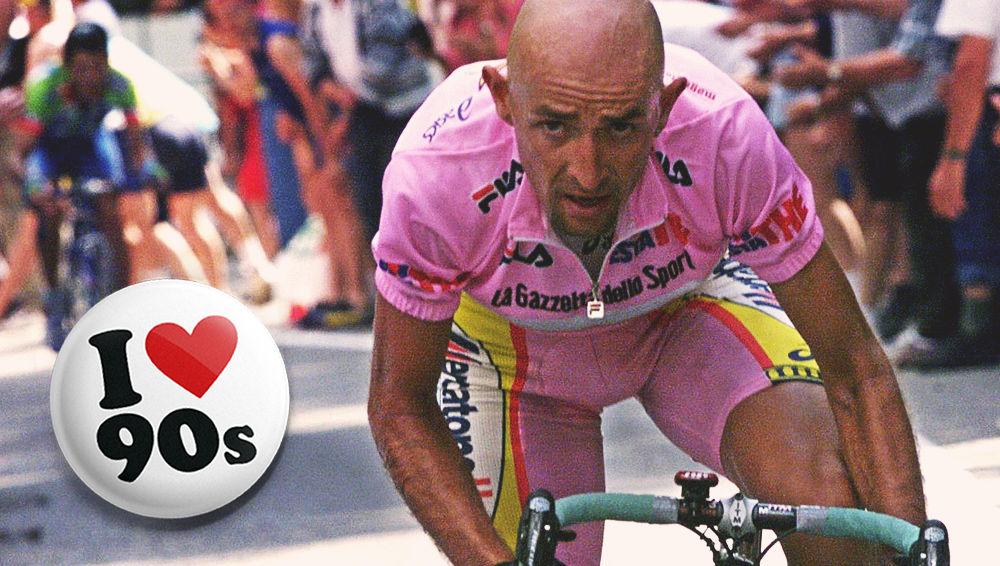

When Marco Pantani left the 1999 Giro d'Italia in disgrace, after being disqualified for a blood haematocrit above the 50 per cent limit, his final words on the steps of the Hotel Touring in Madonna di Campiglio, surrounded by police and media, were emblematic of the huge moment in his career and the decade that was coming to an end.

"I've started all over again after serious accidents before but morally this time we've touched the bottom. Now I just want some respect," Pantani said emotionally, before climbing into a car to try to escape the whole scandal that was about to engulf him and change his life forever.

He was shocked and confused. He had seemingly cracked and was ready to quit the sport but refused to confess to his sins.

It was a huge moment in Italian cycling, a chance for change. If Pantani had told the whole truth about what had happened; about his wildly fluctuating haematocrit, the blood values hidden away in Professor Conconi's clinic, about the EPO abuse in professional cycling in the nineties, he could have set a new course for Italian cycling.

Instead he followed the path of omertà and of denial by suggesting there was a plot, that someone was out to get him, and somehow save the others, because he was too good. It was a denial that is still hurting Italian cycling.

Some doubts and details still remain, but the full picture has emerged over time and became definite in 2016 when Italian police closed the investigation that his mother had pushed so hard for. By then Pantani was dead, consumed by mental illness, cocaine abuse and the anger that had tormented him since that fateful day in Madonna di Campiglio.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Pantani always decided his own destiny throughout his career – he was stubborn that way, despite being frail and skinny as all climbers are. He earned millions thanks to his success. Yet like so many other riders of the time, he was arguably a victim of the system, a victim of the nineties, when riders were openly encouraged to use EPO, protected and assisted, with little chance of being caught.

Pantani was a cycling Icarus, encouraged to climb higher and faster and then convinced that he had never done anything wrong, or at least nothing more than his rivals were also doing.

June 5, 1999: a long and dramatic day

I was at the 1999 Giro d'Italia. I can remember the moment the news emerged that Pantani had failed a haematocrit test. It sent shock waves through the race, Italy, the sport and the world.

By then doping cases, stories of EPO abuse, police raids and the other scandals had sadly become regular occurrences. But this was still huge. Pantani was leading the Giro d'Italia, wearing the pink jersey and was the idol of millions of tifosi who had fallen in love with cycling thanks to this quietly-spoken, balding kid from Cesenatico, who won with solo attacks in the mountains of the Giro d'Italia and Tour de France.

I was at much of the 1998 Tour de France and later reported on the police blitz after a stage of the 2001 Giro in San Remo and the subsequent strike by riders, including Pantani, but 1999 and Madonna di Campiglio was a far bigger moment. Only Pantani's death and funeral in 2004 left a deeper scar on me as a journalist and a cyclist, due to the sheer sense of tragic loss that could and should have been avoided.

I was travelling with hugely experienced journalist Mike Price at the 1999 Giro d'Italia. He was there for the Reuters news agency, I for Cycling Weekly. We had slept down the valley from Madonna di Campiglio the night before the stage and were ahead of the race when a phone call from photographer Graham Watson told me that Pantani had failed a haematocrit test. I almost crashed the hire car we were in and had to stop to fully understand the enormity of it all.

As soon as the news that Pantani was out of the Giro d'Italia was confirmed, we filed some initial reports and then high-tailed it to the finish of the stage in Aprica to set up base. We knew it would be a long, dramatic day.

The stage was won by Roberto Heras but few cared and even fewer will perhaps remember. The day was about understanding what had happened to Pantani and why. It was a turning point for the sport.

The wider picture was very complex; this was about more than just Pantani's haematocrit. The presence of UCI president Hein Verbruggen in Madonna di Campiglio raised suspicions amongst many in Italy, fuelling the idea of a complotto against Pantani.

During the 1999 season, the Italian Cycling Federation had also tried to introduce a series of blood and urine tests before and during the Giro d'Italia, but many riders had opposed the so-called ‘I don't risk my health’ tests, apparently afraid of what they might reveal. The UCI had also tried to block the extra tests, claiming they were responsible for any testing at international races.

Pantani was never afraid to speak out for his fellow riders and usually accepted his role of leader of the Italian gruppo. He made it clear that he was against the regular controls. However, the peloton was divided. The Mapei team owner Giorgio Squinzi and staff were in favour of the tests after their own problems with doping in the nineties. Squinzi insisted that his riders broke ranks with the peloton and underwent the tests.

That angered Pantani, and he went as far as bullying Andrea Tafi during stage 8 of the Giro. Laurent Jalabert was in the pink jersey during the first part of the Giro, with Richard Virenque winning stage 13 to Rapallo. He had constantly denied that he had doped during the 1998 Tour de France despite claims by his soigneur Willy Voet. On the same day Virenque won the stage, he was informed that he had been charged for his role in the Festina Affair.

There were doping allegations and doping stories everywhere at the 1999 Giro d'Italia.

As Pantani drove to a private clinic for blood tests that he claimed showed his haematocrit was below 50%, Squinzi was appearing live on Italian television. He didn't hold back, feeling it was a huge moment in the fight against doping in cycling.

"There is divine, and human justice, at last," Squinzi said. "This phenomenon had to explode sooner or later. I warned Verbruggen four years ago. We can't go on with this deceit and hypocrisy. The haematocrit levels of my riders are on average five per cent lower than when they left [the Giro start in] Agrigento. Don't let them talk crap. If they have around 50 per cent, two days from the end, it means they've taken top-ups."

Squinzi had tried to clean up his own team and was hoping people would agree it was time to clean up the whole sport. He was wrong, perhaps a decade ahead of his time. Of course, history shows that he soon walked away from the sport, leaving it to its destiny. Squinzi’s decision came, incidentally, after Mapei’s Stefano Garzelli – a teammate of Pantani in 1999 – tested positive while wearing the pink jersey at the 2002 Giro.

In Italy, the media was somewhat divided and took different stances on Pantani's case. La Gazzetta dello Sport expressed its anger and disappointment but other national titles and especially most television channels were more supportive of Pantani. None had the courage to accuse Pantani of doping or EPO use, preferring a populist approach.

I have no memory of the final stage of the 1999 Giro d'Italia or Gotti's victory in Milan. It soon emerged that he and many of the other riders in the top ten had haematocrit values close to the 50 per cent limit. Many would eventually be caught up in doping scandals.

Pantani became encamped at home in Cesenatico in the days after the Giro d'Italia. He eventually agreed to give a press conference on June 9 in the same country retreat where he had launched his famous Pirata nickname a few years earlier. It was broadcast live on television.

He somehow found the nerve and courage to deny any wrong doing, preferring to fuel the belief amongst the tifosi that there had been a plot against him, perhaps from the UCI or the Italian Federation. Claims that the Naples mafia wanted to him lose the Giro d'Italia due to large bets on his victory also surfaced and would be repeated for years. Any kind of plot was considered to avoid looking for the truth.

Pantani, his family, his team and many others in Italian cycling refused to accept any wrongdoing and thus shed any light on why Pantani's haematocrit was 53% after three weeks of hard racing at the Giro d'Italia.

The sport moved on without Pantani. Lance Armstrong won the Tour de France for the first time that July, starting a whole new decade and new era for the sport.

A tragic missed chance

Over the months and then years that followed Madonna di Campiglio, Pantani became caught up in his denials and entwined in further police investigations. Pantani's difficult relationship with his Danish girlfriend Christina also ended, leaving him adrift with his personal emotions and little desire to ride his bike.

He gradually backed himself into a dark, dark corner, one which he was unable to escape, despite having medical treatment for addiction and mental problems.

Pantani raced on, often as a way to keep him away from recreational drugs and help his rehabilitation. At the Tour de France, he beat Armstrong to win the stage on Mont Ventoux. He won another stage to Courchevel, but then blew up on the stage to Morzine after making a solo attack. He would eventually quit the Tour with stomach problems.

"I tried to blow up the Tour but I was the one who blew," he said.

Pantani rode the Giro in 2001, 2002 and 2003, but was a shadow of himself and even suffered on the climbs. It would later emerge he was still using cocaine and other drugs, and was losing the fight for his sanity. He eventually died of a cocaine overdose in a hotel room in Rimini on St Valentine's Day 2004. By then he was a lost soul, tormented by his past, his addiction and his fragility.

It was a tragic loss and with millions of tears shed on the day of his funeral in Cesenatico. Yet few in Italian cycling seem to have learnt from the mistakes that lead to Pantani's death.

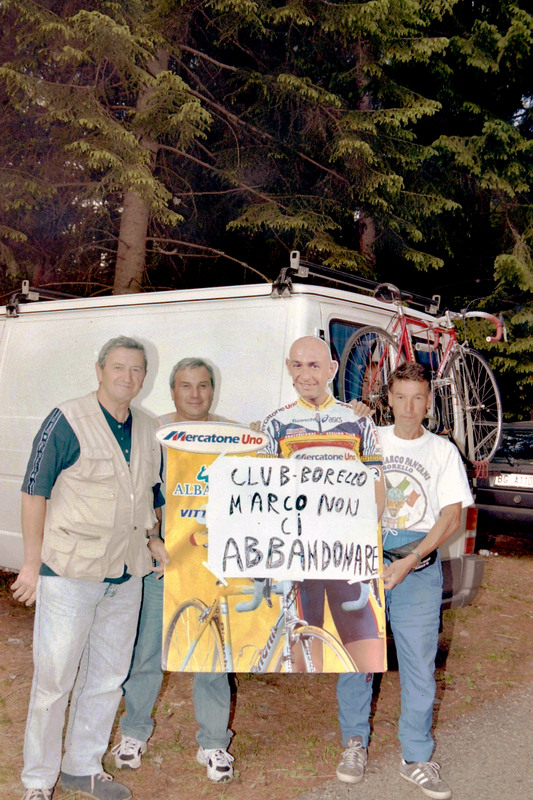

Some fans are still in denial much like Pantani and his entourage. Pantani flags, yellow bandanas and other souvenirs of the Pantani years can still be seen at the Giro d'Italia. Italian cycling failed to learn a lesson from the loss of one of their most successful riders.

At Pantani's funeral, someone read a kind of farewell message he had scribbled on his passport during a holiday in Cuba. It is full of paranoia and pain but sums up Pantani's final thoughts on what had happened to him during his career and life.

"There's not a job where you have to give your blood and where the families of your colleagues are woken up during the night. I was always afraid of being spied on at home, in hotels and by TV cameras. I ended up hurting myself to not give up my intimacy, the intimacy of my girlfriend and of other colleagues who also lost, of other families who, like me, were attacked," he wrote.

"Go and see what a cyclist is really like. How many people were involved in my sadness as I tried to make a comeback with my dreams as a man which were muddied by drugs, but after my life as an athlete.

"This document is the truth. My hope is that real men or women can read it and defend equal rules in sport for everybody. I'm not a liar, I feel hurt and everybody who believed in me has to speak out."

Sadly, silence prevailed after his funeral. Few in Italian cycling, those who know the truth, have found the courage to speak out and tell the full story about what happened to Pantani and why. After the workers had cemented the temporary tombstone in the Cesenatico cemetery, his former teammates and staff stayed silent. Many still work in the sport; they still like to be seen at the Giro, and express their sadness on the anniversary of Pantani's death.

Their silence remains nauseating.

Pantani's expulsion from the 1999 Giro at Madonna di Campiglio could have been a turning point for professional cycling; the huge moment could have helped clean up the sport after the EPO abuse of the decade before.

Sadly, Pantani, his teammates, his fellow riders, and those who aided and abetted him, stayed silent and carried on as usual. It is the tragic legacy of the nineties.

Stephen is one of the most experienced member of the Cyclingnews team, having reported on professional cycling since 1994. He has been Head of News at Cyclingnews since 2022, before which he held the position of European editor since 2012 and previously worked for Reuters, Shift Active Media, and CyclingWeekly, among other publications.