Marco Pantani: A Valentine's day to remember

A decade since the death of 'Il Pirata'

Later this week marks a decade since Marco Pantani, one of cycling’s most flamboyant characters, was found dead in a Rimini hotel room. His fantastic successes at a time of the sport’s greatest excesses have produced a vibrant yet tarnished legacy. This is the first in a week-long look back at the Italian rider's career. This article originally appeared in ProCycling magazine.

On 14 February each year, most celebrate St Valentine’s day with a gift of flowers as a display of love to someone important in their lives. For the tenth year in a row, it will be a day of grief and remembrance for Tonina and Paolo Pantani as they visit their son’s grave in the Cesenatico cemetery.

They will not be alone. Each year, 50 thousand people visit the white stone grave the Pantanis had built near the back of the cemetery. It may be 10 years since Marco Pantani died of a cocaine overdose but ‘Il Pirata’ has never been forgotten.

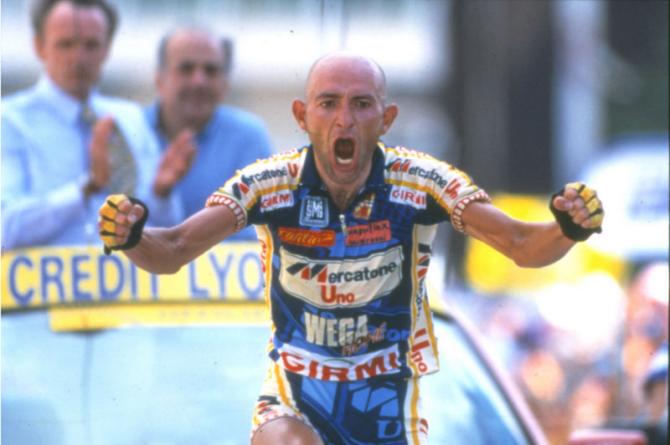

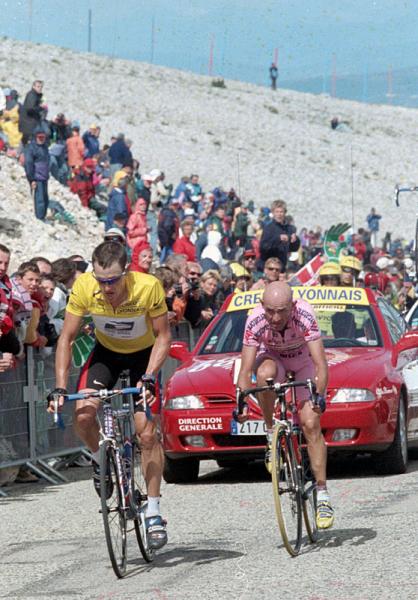

The tiny Italian climber who won both the Giro d’Italia and Tour de France in 1998 somehow touches people’s hearts far more than other riders did. His fragility was endearing, his audacious attacks were inspiring and his melancholic eyes made it possible to empathise with his sadness.

Pantani’s professional career lasted from 1992 until 2003. It was a rollercoaster of heady successes, terrible accidents and remarkable comebacks that was derailed by a failed haematocrit test while he led the 1999 Giro d’Italia. He would never fully recover from that day in Madonna di Campiglio and began a long descent into addiction and depression that ultimately resulted in his death in the Le Rose hotel in Rimini.

Ten years on, the accusations and evidence of doping remain, blighting Pantani’s place in cycling history. It is now almost certain that he used EPO for much of his career but despite seven police investigations and damning evidence from Professor Francesco Conconi’s research files, Pantani never confessed. He took his version of the truth to the grave.

For many, especially in Italy, he remains a victim of the system, a fall guy for a generation of dopers, a man whose pride stopped him from speaking out and led to his inner demons destroying him.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Pantani would have been 44 on 13 January this year. He could have been part of the solution to professional cycling’s problems. Instead, his obituary is a damning review of the wild doping of the 90s and one more reason why it must never be allowed to happen again…

I interviewed Pantani several times during his career. I was on the Champs-Élysées under the podium when Felice Gimondi raised Pantani’s hand in celebration of an Italian victory. I covered the 1999 Giro d’Italia, the dramatic events at Madonna di Campiglio and Pantani’s denials and lies in the aftermath.

He often referred to himself in the third person during interviews and liked to provoke his rivals, especially Lance Armstrong, but his sensitive, frail nature was easy to perceive. He was strong in the mountains, where he danced on the pedals, yet he was actually as fragile as a sparrow and became engulfed by his own fame and popularity. Being thrown out of the 1999 Giro after riding so well broke his wings forever. He would never be the same despite several comebacks and visits to rehabilitation clinics.

Former 1998 Tour de France team-mate Mario Traversoni often went fishing and hunting with Pantani. He believes ‘Il Panta’ could have and should have been saved from his early death. “The only thing that I’ve kept and that interests from my career is the yellow jersey Marco gave me after the Tour ended in Paris and we’d all dyed our hair blonde,” Traversoni recalls now.

“He was special. He was focused on his objective, so he wasn’t a great leader but he didn’t need to be. He was so inspiring, we knew what we had to do just by catching his glimpse for a second.

“It was tragic what happened to him. I’m convinced he could have been saved, that he could be with us now, if he’d been surrounded by the right people who really knew to put Marco’s interests first. Unfortunately, the world of cycling is very ungrateful and full of people who only think about winning and not about their friends.

“Marco always stuck up for people and helped them but nobody was there when he needed help. And I point the finger at the Tour de France organisers, too. Marco saved the 1998 Tour after the Festina affair. We were ready to all quit the race and go home but he stayed on, went on the attack in the Alps and ensured the race made it to the finish in Paris. Yet in 2003, when Pantani needed a hand and an invitation for the Tour to stay on the straight and narrow, the organisers turned their backs on him. He was devastated.”

When Pantani announced his retirement in September 2003, it marked the point were he was no longer able to climb out of his pit of misery and addiction. He seemed to accept his fate and did little to try and stop it taking his life, paying the ultimate price for his mistakes, his pride and his secrets.

Ten years on, little has been learnt about what caused his tragic downfall. Cycling has not yet tried to understand the devastating effects doping has on riders. So much could be learnt from Pantani’s life and his death. But most people who knew exactly what he did during his career – the drugs he took and the pain they caused – remain silent.

Directeur sportif Giuseppe Martinelli refuses to talk about the subject, preferring to bask in the glory of Vincenzo Nibali’s career at Astana. Former team-mates gathered to recall the Mercatone Uno team in December but no one wants to lift the lid on what they did while wearing the yellow jersey and riding for ‘Il Pirata’.

A decade after his death, Marco Pantani deserves a better legacy.

A mother’s tale - Tonina Pantani’s decade-long road to recovery

Tonina Pantani has always strenuously defended her son’s name and honour. In the years immediately after his death, she suffered from depression and hit back at anyone who made allegations about Pantani’s career and problem with drugs. She subsequently investigated his death and the months leading up to it.

While Matt Rendell’s book The Death Of Marco Pantani remains the definitive biography of Pantani’s life. Tonina’s book In The Name Of Marco, co-written with Italian journalist and self-acknowledged Pantani fan Francesco Ceniti, tells the story from her point of view. In it, Tonina finally concedes that her son may have used EPO during his career.

“I honestly don’t know if Marco took that stuff, perhaps he did some times. Perhaps he thought ‘I’m not going to be the only idiot not to do it’” she writes.

“However, after what happened at Madonna di Campiglio, he had decided to tell the whole truth. But they wouldn’t let him. He should have listened to his instinct. He would have got a huge weight off his shoulders and helped reveal the truth.”

In remembrance of her son, Tonina has created two teams for school children in Italy and Croatia and helps organise the annual Pantanissima Gran Fondo in the Dolomites each summer. She continues to receive letters from people all over the world who were touched by Pantani’s career and his death.

“People tell me all the time that no other rider has ever given them emotions that Marco gave them when he went on the attack. ‘We saw how he went past his physical limits to win.’ ‘He beat everyone: doping or no doping.’ ‘Everything is just envy’” she writes.

“It makes me cry when I hear comments like this. I realise that Marco could have been here to enjoy all of this affection. Instead, they destroyed him.

“He loved cycling. And I’m sure that Marco would have fought for clean cycling if he’d had the chance. He can’t now but I want to do it if I can.”

Stephen is one of the most experienced member of the Cyclingnews team, having reported on professional cycling since 1994. He has been Head of News at Cyclingnews since 2022, before which he held the position of European editor since 2012 and previously worked for Reuters, Shift Active Media, and CyclingWeekly, among other publications.