Man-eating bears and walls of snow: How the Tour de France conquered the Pyrenees

How the great mountains of Southern France became a legendary part of the Tour

The Pyrenees have been the setting for many of the Tour de France's most legendary tales: Lapize on the Aubisque, Merckx attacking on the Tourmalet en route to Mourenx, Ocaña crashing in a storm on the Col de Menté, Indurain cracking on Hautacam, Froome visibly holding himself back for the sake of Wiggins on the climb to Peyragudes. The mountains themselves come with a legendary origin myth.

All of us know the story of how the Tour de France first came to tackle the Pyrenees in 1910.

How Alphonse Steinès badgered Henri Desgrange to include the high mountain passes of France's southern border. How Desgrange finally relented and sent Steinès south to scout a route for the Tour to follow. How Steinès had a nightmare experience on the Col du Tourmalet but still cabled his boss that all was well and the mountain was perfectly passable. And how Desgrange then announced the addition of the Pyrenees to the Tour's itinerary and how two dozen riders immediately abandoned the race, before it had even begun, fearing they would be eaten alive by the savage bears that inhabited the mountains of the region, mountains the locals dubbed the Circle of Death.

It's a fabulous story, one of the best we tell about the Tour's early years. But like so much of the Tour's mythic history, little if any of it happened the way we say it did.

The idea of taking the Tour into the Pyrenees had first been publicly mooted by Henri Desgrange during the 1909 Tour. The race had just passed its halfway point and the outcome was already a foregone conclusion: a runaway victory for François Faber. Looking for a way to make a more exciting race, Desgrange wrote in L'Auto that "next year we have to go to Tunisia and Algeria, and to tackle the Pyrenees head-on as we tackle the Alps."

Tackling the Pyrenees was the brainchild of Alphonse Steinès, whose responsibilities included drawing up the route of the race each year. The 36-year-old Luxembourger had in previous years succeeded in convincing Desgrange to take on the Ballon d'Alsace in the Vosges (1905), to tackle the Col Bayard in the Dauphiné Alps (1906), and to climb the Col de Porte in the Chartreuse Massif (1907).

Two months after the end of the 1909 Tour, the route of the 1910 race was announced in the pages of L'Auto. "The Tour de France will enter the Pyrenees, which it has only been touching the edge of," the paper announced. "The first stage will go from Perpignan to Bagnères-de-Luchon (289 km), and the second from Bagnères to Bayonne (325 km)."

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

While the exact cols to be crossed were not named, save for the Col de Port and the Col des Ares, sufficient details were given for readers with knowledge of the area – or access to a good atlas – to work out for themselves which mountains the race would climb.

Several times over the next few months the route of the race was revisited in the pages of L'Auto.

Starting in April 1910, Georges Abran – the Tour's Inspector General – set out to drive the full route of the race, a task that would take him two months to complete. Abran's job was to identify in advance any problems the race might encounter and to liaise with locals: glad-handing mayors, meeting L'Auto's local stringers and sorting out who would man the controls the riders would have to sign in at (to prove they were following the full route of the race and not taking shortcuts).

Between May 19 and 23 Abran crossed the Pyrenees. He was joined for this part of his journey by Charles Ravaud, one of L'Auto's editors. As had happened since he had left Paris on April 15, Abran's progress was reported in the pages of L'Auto.

The route of the first Pyrenean stage presented few challenges and L'Auto reported that Ravaud and Abran successfully crossed the Col de Port and the Col de Portet d'Aspet. The second stage presented more of a challenge. Ravaud and Abran were able to cross the Col de Peyresourde but their attempt to cross the Col d'Aspin was stymied by snow:

"There was only us and tall and cramped walls of snow," they wrote in L'Auto, "and we could not cross the summit where eight meters of snow was piling up. The road was gone!"

The next day they attempted to cross the Col du Tourmalet but again were turned back:

"The Col du Tourmalet, which pierces the sky at more than 2,100 meters in altitude, did not want to be violated any more than did the Aspin."

"It's an avalanche of broken brakes, of tyres torn off or punctured by flints"

The Col du Soulor, Col de Tortes and Col d'Aubisque – a three-for-the-price-of-one Pyrenean ordeal between Argelès-Gazost and Eaux-Bonnes – were also left unviolated.

L'Auto sought to reassure everyone that, despite Abran and Ravaud's failure to drive the full route of the stage, all would be well when the Tour reached the Pyrenees:

"At this time of year, it is normal for snow to remain on the high peaks. [...] However, if our comrade Ravaud and our inspector general Abran could not cross the Cols d'Aspin, Tourmalet and Aubisque, it does not follow that in July we will not cross them. No, these Pyrenean stages will certainly be tough, but they will not be impossible. On the contrary, good weather will bring good roads and the Tour de France – brushing the Iberian Peninsula, after having touched Belgium, Luxembourg, Lorraine, Switzerland, Italy and the Atlantic Ocean – will be the real Tour de France, the most colossal event in the world."

In the middle of June, two groups of riders – from the Alcyon and Legnano teams – set out to reconnoitre the Pyrenean stages and on June 20 they joined together, forming a 13-strong group of riders that attempted to cross the Col du Tourmalet. They were accompanied by Alphonse Baugé, the Alcyon directeur sportif, and the previous day L'Auto had published a letter from him to Charles Ravaud, reporting his crossing of the Port and the Portet d'Aspet over the previous two days:

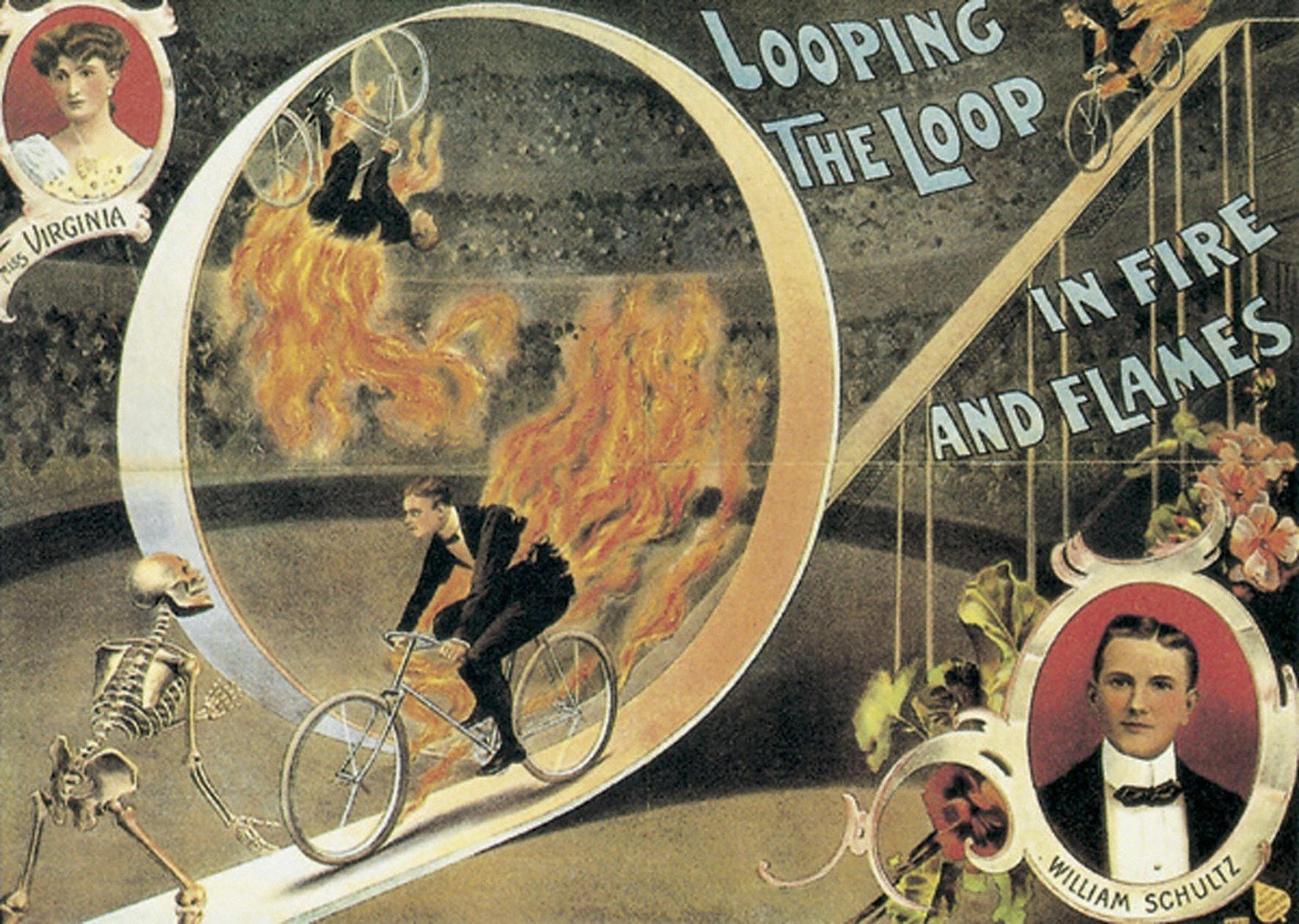

"Ah! my friend, where the hell does Mr Desgrange take us? In truth, it's frightening, and I'm convinced that never has a professional cyclist got himself into shape on similar roads. What hills, and especially what descents! It's 'Looping the Loop'; it's a beautiful 'Circle of Death', it's an avalanche of broken brakes, of tyres torn off or punctured by flints, in two words: it's frightening! And, it seems, Luchon to Bayonne is even worse!"

Baugé was right about Luchon-Bayonne being even worse. It was much worse.

"The road on the Tourmalet does not exist"

Despite a report in L'Auto saying the Tourmalet was open Baugé's car was stopped by snow before reaching the col. "The road on the Tourmalet does not exist," Baugé wrote. "It is lost under six to eight metres of snow." The riders pressed on and then had to descend to Barèges by sliding down the mountain with their bikes held behind them acting as brakes. Georges Cadolle, slipping on the snow, almost fell off a precipice. Louis Trousselier, winner of the 1905 Tour, fell into a swollen river. It took the riders four hours to travel 13 kilometres, most of them downhill.

The next day the riders took on the three-in-one climb of the Aubisque via the Soulor and the now disused Tortes: "Our riders had to cling to Baugé's car to climb it," L'Auto reported. "They covered 36 kilometres in seven hours."

The start of the Tour was just over a week away, July 3, and the race was due to cross the Pyrenees between July 19 and 21. Despite the earlier assurances that all would be fine come July, a panic now set in in the offices of L'Auto. As well as the trials and tribulations of the Alcyon and Legnano riders, the paper had also received letters criticising their plans to take the Tour through the Pyrenees. The possibility of needing to change the route of the race was publicly conceded. But first Steinès was dispatched to the mountains to see for himself the true state of the roads to be used by the Tour.

Steinès arrived in Bagnères-de-Luchon on June 27 and across five days – June 28 through July 2 – L'Auto carried detailed reports of his journey. As well as driving over the cols to be climbed by the riders Steinès met with more than half-a-dozen engineers responsible for the roads of the region, getting assurances that all would be well come the third week of July.

Before setting out to cross the Peyresourde and the Aspin, Steinès sent a message back to Paris: "I will telegraph you this evening the result of our explorations but as of now I can tell you that much has been exaggerated this way and that with claims that it was easy to pass when others said it was impossible. It is neither impossible nor easy, it is simply doable."

"I nearly paid for this reckless folly with my life"

The next day, L'Auto received a message from their stringer in Barèges, the town situated near the base of the descent from the Tourmalet:

"BAREGES, 28 June – Alphonse Steinès crossed the Tourmalet on foot last night at 10 o'clock – Lanne-Camy"

On July 1, L'Auto published Steinès's account of his night in the Tourmalet. "Were I to live to be a hundred," Steinès wrote, "I would always remember the adventure of my struggle against the mountains, the snow, the ice, the clouds, the ravines, the darkness, the cold, against isolation, against hunger, thirst, against – in a nutshell – everything. All that Baugé wrote, all that the riders told Ravaud, is accurate. Nothing was exaggerated. As it is now, it is madness to try and cross the col."

It was early in the evening of June 27 that Steinès, aboard a 16 HP Dietrich driven by Isidore Estrade-Berdat, had set out to drive over the Tourmalet, accompanied by one of L'Auto's recently appointed stringers in the area, Paul Dupont, who would be helping with the stage finish in Bagnères-de-Luchon

Two kilometres before the summit, the road was blocked by snow. A shepherd was tending a herd of cows nearby. Steinès quizzed him on the state of the pass. Deciding that the shepherd's responses were too vague he resolved to find out for himself. Leaving Dupont and Estrade-Berdat to take the Dietrich back down the mountain Steinès, guided by the shepherd, set out on foot for the summit. It was seven o'clock in the evening. "I had promised our Director to see for myself, and I wanted to get through at all costs; I nearly paid for this reckless folly with my life."

What followed has become a legend, embellished and exaggerated. Elements of the Alcyon and Legnano riders' travails on the Tourmalet have become part of Steinès's travails. A passing comment in Steinès's report for L'Auto about bears from Spain has been transformed into imaginary editorials written by Desgrange warning riders in the 1910 Tour to be wary of ursine predators.

His time on the mountain that night has been stretched into the following morning despite the fact that, without the assistance of the search parties sent out to look for him, Steinès had arrived in Barèges at ten o'clock and was eating a meal in his hotel by ten-thirty. Not least, the message telegraphed to Paris by Lanne-Camy has been rewritten and attributed to Steinès himself.

Such is cycling's mythic history, in which facts give way to fables.

Such are the Pyrenees: legendary mountains, with a legendary origin myth.