Magnani: An American in the Giro d'Italia - Excerpt

The forgotten story of the Illinois native, concentration-camp survivor and cycling champion from Heart of Lions, The History of American Bicycle Racing, 2nd edition

In professional road racing's Golden Age in Europe in the 1930s-40s, Magnani was the lone American racing against Fausto Coppi, Gino Bartali, and the rest of the boys in the band.

The Giro d'Italia, yet another victim to the coronavirus sweeping the globe, won't be held this year for the first time since 1946 when the Giro had finally resumed after five-year hiatus imposed by World War II. The 1946 Giro started on June 15 in Milan with a field of seventy-nine starters – all Italian, except for Joseph Magnani, an Illinois native and the first U.S. rider in the Giro d'Italia [1924 Giro winner Guiseppe Enrici was born in Pittsburgh but raced as an Italian -ed].

Magnani rode on the seven-rider Olmo team, sponsored by his friend and rival Giuseppe Olmo, who had retired from racing in 1938. Olmo had won a gold medal in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics 100-kilometer team time trial followed by a professional career in which he won numerous Giro stages, twice captured the Milan-San Remo spring classic, and reigned as Italy's road race champion. For his new Olmo Biciclette, Olmo adapted the Giro's pink and white colors of the leader's maglia rosa for not only his squad's racing colors but also for Olmo Biciclette, which continues in his home town of Celle Ligue.

Magnani was born in LaSalle, Illinois, a coal-mining town in the middle of the Prairie State. He grew up in the village of Mount Clare, between the state capital in Springfield and St. Louis, according to his youngest brother, Father Rudolph Magnani, a Catholic priest in Bethesda, Maryland.

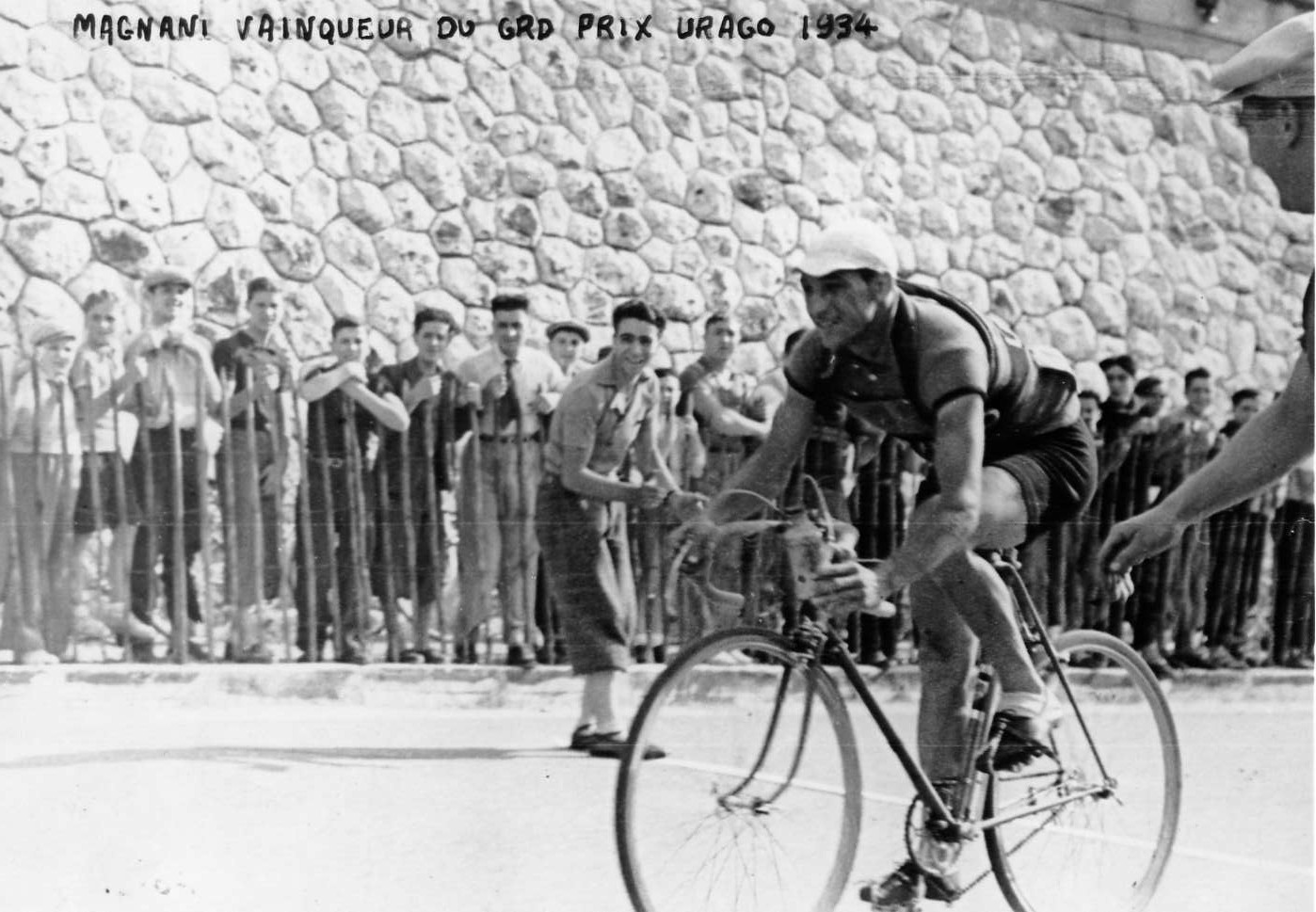

During Magnani's career, road racing in the United States consisted of local amateur clubs holding events. (The Amateur Bicycle League of America, predecessor to USA Cycling, wouldn't introduce the national road racing championship until 1964). He moved at age sixteen in 1928 to a small town near Nice, within sight of the purple-colored Maritime Alps bordering Italy. He joined the amateur Club Cyclo-Touristes, sponsored by Urago Cycles, a family-owned business in Nice. In 1934, Magnani won the Grand Prix Urago against a field of eighty-five. In fifteenth place was his Italian friend Fermo Camellini, destined to win Paris-Nice, Flèche Wallonne, and two Tour de France stages.

Magnani stood an inch under six feet tall with sturdy shoulders. The French press described him as thin and strong. He had a wide forehead, a small chin, and a thick mat of dark hair parted in the center and combed back.

Two dozen other French bicycle companies – among them Peugeot, Terrot, and Automoto – supported professional teams. Thousands of hopefuls vied for only a small number of berths. "Getting a contract for one of the pro teams was tough," his widow, Mimi, told me.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In winter months, Magnani chopped firewood and shoveled coal for hours before hauling loads around for deliveries, which strengthened his upper body while earning money during the Great Depression. He told an interviewer that he prepared for the next racing season early by training for four thousand kilometers (about 2,500 miles).

In 1935 Urago Cycles offered him a coveted pro contract. Entry-level pros like Magnani received bare basics: a bicycle, a set of wrenches, an allowance of tires, a couple jerseys and shorts inscribed with the sponsor's name. Neo-pros lived on their prize money. Sometimes sponsors paid a small bonus for victories – if press coverage mentioned the brand, or if the rider's photo in his team jersey appeared in the newspaper. Pros with victories could negotiate appearance fees, which promoters doled out to drum up pre-race publicity.

One of the first regional spring classics along the French Riviera was the 125-miler from Marseille to Nice. Dating from 1897, Marseille-Nice winners included French Gustav Ganay, mentioned in Ernest Hemingway's memoir, A Moveable Feast, and 1920s Italian superstar Alfredo Binda, three-time world road champion.

In the final kilometers of the 1935 Marseille-Nice, five hours after departing from Marseille, Magnani slid back through the peloton and dropped off the rear unobserved before he jinked, squirrel-like, and rushed up the outside, faster than the peloton. He escaped and bowled up the road as though he could see the finish line. Alone, he gambled. If the peloton caught hm, his legs would have little left for the dash to the finish line in the harbor in Nice. All he needed was to stay away for about ten minutes. He sliced the tangents of turns faster than the peloton could manage. Spectators lined the road and yelled encouragement. Every quick turn of the pedals took him closer to the finish until at last he flew across the line in a solo triumph.

He became the first American to win a professional road race on the Continent. Marseille-Nice was last run in 1959, yet it is still listed in VeloPlus, the Belgian cycling record book, citing the 1935 winner: Joseph Magnani (USA).

That season Magnani won the Grand Prix Waldorf in Nice. In 1936 he joined Urago teammates in the seven-day Tour of Switzerland, up and down the Swiss Alps on a 1,070-mile course. Its topographical profile resembled a row of shark teeth. On the fifth stage, he scored third place. He finished the Tour of Switzerland in eighteenth place in general classification, based on total elapsed time.

Magnani impressed French journalists. L'Auto (predecessor to L'Equipe) published a feature about him by José Meiffret, himself illustrious for setting motor-pace records into his late forties as the fastest cyclist in the world. Meiffret exclaimed to readers: "Attention! Follow this man! Urago has on its hands a rider of great quality."

"There wasn't much money in the 1930s," Mimi told me. "The Great Depression was on. What kept him racing was that he was making a pretty good living."

Earning a good living meant persevering despite horrendous weather, such as his 1938 victory in the 149-mile Marseille-Toulon-Marseille Riviera classic held during a torrential rainstorm. All but four of eighty entrants quit.

That year Magnani drew considerable press attention in the 940-mile Tour de L'Est Central, sponsored by Dubonnet wine. It boasted a hefty prize-list of 90,000 francs. On stage 5, from Vichy to Saint Étienne, Magnani shot off the front of the peloton up the last hill after 110 miles and time trialed the remaining few miles to the finish on the Vélodrome de l'Etivalliè. He won by a minute. That boosted him to second overall, which he kept when the race concluded three days later.

One enduring result came in the 1938 Paris-Nice. Since it starts in chronically overcast Paris and heads south for eight days to the sun-splashed Riviera, it is called the Race to the Sun. On the last stage, Magnani attacked up a hill and into a headwind with five others to forge a successful breakaway. The time he and cohorts gained on the peloton that stage lifted him to finish ninth overall.

He also competed in the Italian classic, Milan-San Remo, for the second time in 1938, when its winner was Giuseppe Olmo. Magnani finished a respectable twenty-ninth. He won the two-day Circuit of Lourdes, featuring steep climbs up the highest peaks of the Pyrenees bordering Spain, and treacherous descents at breakneck speeds down narrow, snaking dirt roads hugging cliff edges. He also set a new hour record for the Nice velodrome, pedaling forty-two kilometers (26.2 miles). The monarch of the Nice track was L'Américain.

In 1939 Magnani, 27, was riding at the top of his game as a member of the Terrot-Hutchinson team, headquartered in Dijon, famous for mustard. He won the first leg of the 11-stage Tour of Southeast France, which went 1,250 miles. He pulled on the leader's blue jersey, the color of the sponsoring newspaper's pages. He also claimed third place in stage 3. After he first week, he lost the lead and finished seventh overall. He also won the Lyon-Saint Étienne one-day race.

Elsewhere on the Continent, however, German soldiers supported by tanks invaded Poland. Hundreds of thousands of civilians fled with belongings they packed on a moment's notice. Great Britain declared war on Germany, mobilized its military, and drafted tens of thousands of young men into service to fight across the English Channel. In the spring of 1940 German tanks blitzed across northern France and overwhelmed the French army. German troops marched into Paris and seized government buildings.

The German military moved the Union Cycliste International headquarters from Paris to Berlin. The crisis cancelled the UCI world championships set for Italy, wiped out the Summer Olympics scheduled for Japan, and scrapped all three of the Grand Tours.

On December 7, 1941, Japanese planes bombed the U.S. Naval base in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared war on Japan. Then Germany and Italy declared war on America. The U.S. armed forces rapidly ballooned to more than 12 million men and women serving in uniform in Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific.

Then thousands of German troops stormed southern France. Their occupation turned severe. Magnani became a marked man. To outward appearances, he appeared inconspicuous, spoke French like a native. But he carried a U.S. passport. To armed German occupiers, he might as well have been wearing a bull's eye on his chest and back.

"The Germans arrested Joe because he was an American," Mimi said. "They put him in a concentration camp in the north of France."

"Joe was practically starved in the concentration camp," said Joseph's younger brother, Father Rudolph Magnani. "Our family sent him care packages with food, but we had no way of knowing how much got through to him. His weight dropped from 170 pounds to 98 pounds."

On June 6, 1944, the biggest armada invasion in world history began with 160,000 U.S. and British troops assaulting northwest France. On August 24, Allied Forces rolled into Paris, liberating the City of Light. A short while later, Magnani was rescued. He joined his wife in Nice. Their son was born in July 1945, named after Joseph's brother, Rudolph.

Magnani was hired onto the France-Sport team. He raced in a busy 1945 schedule along the Riviera and around Paris. His comeback was noted by Giuseppe Olmo, who signed him to ride in the pink-and-white colors of his Olmo squadra for the 1946 season.

Italy's three-week Giro had been suspended for five years, making the 1946 Giro a passionate theater for all Italian teams. Olmo picked Magnani to ride the Giro. Magnani rode support for the team captain and his friend Fermo Camellini, noted for his swiftness up mountains and the punch he had in his legs for sprinting. Camellini was a contender against previous winners and national icons Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali.

During the second week, Camellini wore the race leader's maglia rosa jersey for three stages. Then Magnani fell heavily in a pileup. "He banged up his knee and couldn't race because of infection, so he came back home to recover," said his wife.

Camellini lost the leader's jersey while Coppi and Bartali dueled, with Bartali victorious.

Magnani pulled out of the Giro, but he added that Grand Tour to his lengthy list of firsts for U.S. racers on the Continent. In 1998 he was inducted into the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame.

Excerpted from Hearts of Lions: The History of American Bicycle Racing, second edition (University of Nebraska Press), by Peter Joffre Nye. Save 40 per cent with Code 6AS20, on the publisher's link here. Nye is a prize-winning author of nine books, and a magazine editor and journalist who has contributed to the Washington Post, USA Today, Sports Illustrated, and Humanities Magazine.

Peter Joffre Nye is author of the updated second edition of Hearts of Lions: The History of American Bicycle Racing (University of Nebraska Press).