Lizzie Armitstead: The busy life of a new world champion

Best of Procycling in 2015

This feature first appeared in Procycling magazine. To subscribe, click here.

Procycling’s cover star for the December edition of the magazine was freshly-minted world road race champion Lizzie Armitstead. As soon as she crossed the finish line, we started making plans to interview her and get her on the cover as soon as possible, which resulted in a coveted hour-long slot in her newly busy schedule and a feature interview well before any other cycling magazines got a look in.

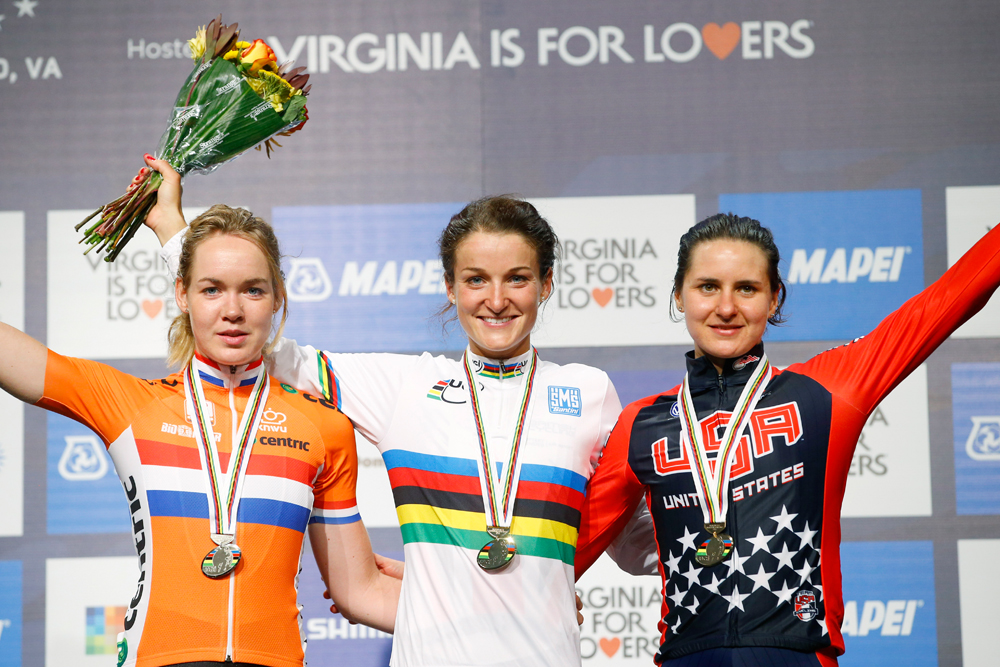

Despite two overall wins in the women’s World Cup and numerous international victories, Lizzie Armitstead was developing a reputation for near misses in the very biggest events. But she removed what she described as a “monkey” from her back when she dominated the World Championships road race in Richmond, Virginia, with an attacking ride and superb sprint for gold. Armitstead is the fourth British woman to wear the rainbow jersey. Procycling went to meet her to find out what makes Lizzie tick.

Lizzie Armitstead, all hectic energy and busy cheer, shoves an armful of shopping bags – H&M, River Island and Harvey Nichols – containing clothes, more bags and a leopard-print shoebox, at me. “Here, hold these please,” she says, and then disappears off with the photographer from The Times.

Life just became a bit busier for new world champion Armitstead, the sixth British rider, and fourth British woman, to win a senior road race rainbow jersey. There’s media (“I won’t finish until seven tonight”), shopping (“I hate shopping”), a holiday (“I don’t even know where I’m going yet – got any ideas?”), a family diamond wedding anniversary which has taken precedence over a trip to Abu Dhabi for the UCI’s end-of-season gala and a wedding to Team Sky rider Philip Deignan to plan. You might think that fitting all this around everyday life might be complicated but this is everyday life for Lizzie Armitstead now.

Not that she was prepared for it. Armitstead’s focus on winning the world title involved detailed planning over a period of months and a perfect imposition of tactics and physical presence on the race itself. That focus and planning went all the way up to the end of the race in Richmond, Virginia, but it didn’t extend to the other side of the finishing line.

Tell us about being the world champion, Procycling asks Armitstead on her return from being photographed.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“It’s still quite surreal. Because I wasn’t prepared for it,” she says. “I didn’t think at all about afterwards. The off-season was an afterthought. I was just focusing on that day.

“I suppose the only time I really get to reflect on things is when I’m riding my bike. I’ve not done that yet, so maybe when I go out for a ride, I’ll see my rainbow stripes and feel better.”

Armitstead does have one reference point: the silver medal she won at the London Olympics. As Britain’s first medallist of the Games, she was briefly the centre of a huge amount of media attention but even given the difference between the scale of the two races, winning a gold medal is very different to winning a silver. On reflection, Armitstead says, she has begun to understand what she has done. “I did see it written down somewhere, Lizzie Armitstead, world champion, and that was a little moment,” she says. “I feel confident. I feel proud of myself. I feel… I don’t know…”

“Validated?” I suggest.

“Good word. Exactly,” she says.

For most of the women’s World Championships road race, all but about 10 metres of it, to be exact, I thought Lizzie Armitstead wasn’t going to win.

There were several good reasons for this, which seemed convincing at the time. I thought the dangerous-looking mid-race break was going to stay away – with riders from most of the strong nations represented, I couldn’t see who was going to chase it down. The television coverage hardly showed any time gaps, nor much in the way of pictures of the Dutch and German teams, who were actually pulling at the front of the peloton, off-camera. So it was a surprise when the telephoto lens shot before the climb of Libby Hill, with only four kilometres to go, showed the peloton looming just a few seconds behind the remains of the break, with two riders – Lauren Kitchen and Valentina Scandolara – dangling precariously off the front. (In terms of good quality television coverage, it was terrible. But paradoxically, the adrenalin shot of suddenly realising that the race was wide open, instead of the normal slow reveal of a reducing time gap and the anti-climax of the catch, made the race seem incredibly exciting, in much the same way as happened with Stephen Roche’s comeback in the 1987 Tour de France at La Plagne.)

After that, I still thought Armitstead wouldn’t win, because she accelerated on 23rd Street, without going away. Last chance, I thought. Then she attacked again up Governor Street, and while she stretched and then broke the peloton, it wasn’t enough to leave her on her own. Riders often talk about having one bullet to fire in a race. Armitstead had missed the target twice, by my reckoning. Actually, three times – she’d had a dig the lap before.

Up the finishing straight, and Armitstead was sat on the front of the group, which received wisdom will tell us is the worst place to be. From the final bend, at 700m to go, to about 300m, she led eight other riders, a tall poppy to be cut down.

Second places can be contagious – just ask Peter Sagan. Keen cycling fans might know that Armitstead has won the World Cup two years running (including three wins in individual rounds this year) but at successive World Championships and an Olympic Games, she’d come up short, and it was starting to become a bit of an issue. In London 2012, Marianne Vos was pretty much unbeatable (and Armitstead probably too inexperienced to imagine otherwise). But at the 2014 Worlds in Ponferrada, Armitstead had been the strongest rider, yet still only come in seventh. She’d forced a quartet of riders free over the last climb. But she’d also telegraphed her superior strength, so co-operation broke down and her group was caught before she came a dispirited seventh behind winner Pauline Ferrand-Prévot. I was worried that she didn’t quite have the tactical tools to turn race-winning strength into actual race wins, an eternal second, defined in the public eye by her Olympic silver medal and destined never to improve it. She had been beaten by Vos and beaten by Ferrand-Prévot, and beaten, in some ways, by herself.

On the finishing straight in Richmond, I thought she’d been beaten again, in a similar way to Ponferrada. Strong enough to dictate the race, therefore strong enough for her rivals to try nothing more than to follow, sit on and out-sprint her at the finish.

I tell her it looked like the race had slipped from her grasp.

She looks back at me, and says, “I was completely in control.”

Armitstead has said on more than one occasion since Richmond that in winning the World Championships, she had removed a monkey from her back. It should be pointed out that this monkey is not a British Cycling-style ‘Inner Chimp’ – Armitstead did plan her assault on the Worlds in every bit as much detail as BC applied to Mark Cavendish winning the men’s race in Copenhagen four years ago but it was mainly with her Boels-Dolmans coach Danny Stam. While she had success with the GB track team, she didn’t feel like the methods suited her temperament.

“I couldn’t have continued in that environment. I struggled with it, because I’m a perfectionist and a control freak. As a team pursuiter you’re doing the same training as three other people. And walking into the velodrome every day is exactly the same feeling as I get when I walk into a hospital. I have a physical reaction to it. It makes my skin crawl.”

During the course of our interview, I ask about Armitstead’s parents. The combination of an accountant father and teacher mother is an irresistible one for a journalist – surely the ability to crunch power numbers comes from her father, and the study of road racing lore from her mother. But she’s inherited something more profound from her father, in fact.

“One thing that has always inspired me in cycling is that my dad has never liked his job. I’ve always been aware that he’s hated being stuck in an office,” she says. An amateur psychologist could be tempted to draw interesting parallels between Armitstead’s discomfort with the institutionalised ethos of British Cycling and her perception that her father hasn’t enjoyed the institutionalisation of a life in an office. Armitstead herself admits that she’s not easy to work with. “Or maybe I don’t find it easy to work with other people,” she corrects herself. “I’m confident in who I am. I don’t get taken in and my opinions are often very strong. There are only two people I have clicked with – my first coach, Phil West, and Danny Stam. They have the ability to bring out the best in me.”

I ask her if she enjoys winning races, or whether not losing them is more important to her, and she thinks for a few seconds.

“I probably enjoy not losing,” she says, and pauses. “Is that bad?” she asks.

Armitstead’s Worlds win was a masterpiece of tactics, planning and control, even if she perceives that her greatest assets are her physical strength and her work ethic, rather than a mastery of the dark arts of road racing.

“My strength is physical. I just got it tactically right that once. With my physical ability I should have won more than 10 races this year but I suppose I have more confidence in my physical ability than my tactical ability,” she says.

But the planning behind Richmond was nonetheless meticulous.

“The Championships were in the US, so it was difficult to recce the course more than once,” she says. “I chose to do the Philadelphia World Cup because I knew I could go to Richmond and look at the course at the same time. Had that not been the case, I might not have gone to Philly.”

Though Armitstead won the Philadelphia race, the priority was always the World Championships, and after she’d seen the course, she knew what she had to do to win the race. And the first thing was to tweak her training.

“Generally, going into a World Championships you want massive base condition, and that’s what you focus on, so you are fitter than anybody else. I readjusted going into Richmond because physically I knew my fitness was good but I needed to make sure that those two-minute efforts, and my 30-second power, would be better than anybody else’s.From June onwards, I was doing specific Richmond climbs in training. I knew there would be those consecutive efforts at the end.”

During her training rides in her adopted but temporary home in Monaco, Armitstead would replicate the Richmond efforts every other day at the end of training: 30 seconds on, 30 seconds off, three times, then finishing with a sprint.

There was one other key race in her build-up: the Grand Prix de Plouay in Brittany. Observant riders might have noticed that Plouay and the Richmond Worlds had some strikingly similar characteristics. Both are circuit races and both finish with a flat run-in after a climb. In winning Plouay a month before Richmond, Armitstead was giving herself a dress rehearsal for the Worlds. Up the two-kilometre drag of the Côte de Ty Marrec, with only four kilometres to ride, she attacked and it took a huge effort by Anna Van Der Breggen, her runner-up in the Worlds and main rival for the World Cup, to bring her back. Coincidentally, both races ended with a nine-woman group coalescing for the sprint. Not coincidentally, five of the same women made up those two nine-strong groups.

“At Plouay, I wanted to test my legs and test what was missing. In previous years, I did Plouay and didn’t stick in an attack, because ‘being a sprinter, Lizzie,” – here she is quoting her team management and the general perception of her – “You’ve got to wait for the sprint.’

“Actually, I don’t feel that comfortable waiting for sprints. As a cyclist you get put in a box early on, and because I was a track rider, and had a bigger bum than the girl next to me, I was a sprinter. It’s as simple as that sometimes. At Plouay, I stuck in an attack and dropped anybody who could potentially beat me in a sprint. So in Richmond I knew that’s what I wanted to do. The plan was to put in a move up Governor Street and then sprint.”

Armitstead’s main challenge at the Worlds was actually getting through the race. Physically, she was on top form, but mentally the challenge was tougher.

“I always get bored in races. I struggle with that,” she says. “I’m always wanting to do more. I knew that the Worlds would be bad – I’d have to have a huge amount of patience. My mind wanders – I started thinking about all sorts, like where to go on holiday, my wedding…

“I find it frustrating but I was surprised when I looked behind at one point and there was hardly anybody left in the peloton. I was never under pressure.

“I knew the group of nine would come back. Some of those riders were the second or third-ranked riders in their teams and it wouldn’t have been a sure win for them, so I don’t think their teams would have taken that risk.

“My attack on Governor Street was about stringing it out. I didn’t know where Jolien d’Hoore and Giorgia Bronzini were but I knew they would be struggling. It’s a game – you need to look at your rivals, to look in their faces. My whole game plan in Richmond was to drop Bronzini and d’Hoore. I got it down to nine girls, and I knew they would leave me on the front, so I didn’t put everything into the attack.”

Which brings us back to the sprint on East Broad Street, Richmond. The lead riders rounded the final left turn and the momentum and racing line naturally took them to the right hand side of the road. Ahead, on the opposite side, two Flemish flags fluttered in the wind. They were pointing back along the road, and away from it to the left: cross headwind from the right. Armitstead eased over to the left hand side of the road.

“If you do an attack like that and you take it to one side of the road, you shut down one side. Nobody launched an attack, and that said to me, nobody has the legs to beat me, because they’ve not beaten me the whole season in a sprint, so they’re just waiting for the line,” says Armitstead.

She sat on the front, fiddled with her gears, until she was in her sprinting gear, and waited. Armitstead knew that her rivals would blink before she did.

“Van Der Breggen sprinted but that was the right thing for her. She needed a long sprint. It was a very good sprint, but…”

Armitstead doesn’t finish the sentence. She doesn’t need to. She’d proven the doubters, me included, wrong.