Like the pages of a book - A postcard from the 1996 Worlds

Axel Merckx on his father's shadow and his own breakthrough in Lugano

I can't breathe. I can't lift my eyes from the ground, and I can't hear anything but the clicks of the camera. It's as though the operator is so close he's inside my head. Click, click, click. All I want is for the noise to stop, the space to clear and for the race to start. But, to be honest, I don't really want to race. I just want to lose the television crew and photographer who have come all this way just to watch me take part in a junior provincial race. They're here for me. They're here for my name. They're here because I'm Eddy Merckx's son and the embarrassment from the attention is so intense that I want the ground to swallow me.

Finally, we can race.

It wasn't easy growing up with the Merckx name but I had a wonderful childhood and fantastic parents. There was never any undue pressure and, as a child of the 1980s, I would often come home from school and flick through our VHS collection and watch tapes of my dad racing.

There was always one cassette that drew my gaze the most, with its all-black casing and a thin blue sticker on the side that read in my mum's faint blue handwriting: 'Montreal Worlds, 74'. That was the year my dad won, of course, and I must have watched that tape a thousand times, and to the point where it almost wore through. And even though I knew the ending, knew the outcome to the very second, to the very gesture of his celebration, I would still watch it again and again. And if I was alone – and I probably was after the first 500 viewings – then I'd raise my hands as he won.

I grew up reading about my dad but, when I watched him, it was somehow different. It's hard to explain, but when I was reading about the 'Great Eddy Merckx', it was always someone else's words, someone else's story. But when I watched those tapes, it was all about Dad and me. The man and father that I know. And it didn't matter that I knew the outcome, that he'd cross the line first and raise his hands. It didn't matter because he kept on winning each time.

What I loved most was the fact that anyone could do it, and anyone could race. All you needed was a licence, a bike, and a desire to pour your heart into it. It was – and is – a sport for every boy or girl, and whether I took home prize money, it never really mattered. I was just doing something that I loved.

As I rose through the ranks, I started to gain recognition and began to accept and deal with the name I had on my back. When I started racing, it wasn't easy. There were all these expectations and everyone was watching to see if I would be as strong as my dad. That was always going to be impossible, but it made me tough, and it gave me thicker skin, so after that provincial race, I learnt to deal with how I was going to be my own person and live by my expectations.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

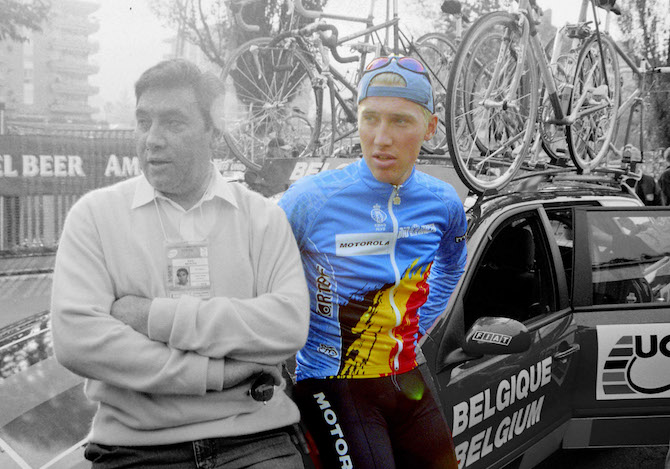

Belgium didn't really go into that race as the main favourites. The pundits all thought that the Italians had the strongest team and, on paper, they probably did, while the course itself was super hard with the Crespera the climb on which Coppi attacked in 1953 to take one of his most famous wins. We had a strong team, too, though. Johan Museeuw was the World Cup leader at the time and, although he hadn't performed in Paris-Tours a week earlier, and the course didn't necessarily suit his skill-set, he was one of the smartest riders around. My job that day was to support Johan as much as possible and I came into the race on great form having ridden the Vuelta. I can remember pulling on the national jersey that morning, putting on my Motorola shorts and cap and thinking, 'Today you can really have a great race.' It was the 1990s, so think pulse meters not power meters, Spinacis not S-Works.

As the race wore on, Johan escaped with a super-strong break that included Swiss local favourite Mauro Gianetti, Pascal Hervé of France, and two riders from the Italian team, Fabrizio Guidi and Andrea Ferrigato. This put the Italian team in a difficult place because, although Guidi and Ferrigato were decent riders, they weren't the best riders on the Italian team, and Gianetti had two men with him. The Italians waited and waited and soon the break had three minutes. My job at that point was to hold back and just let the race play out. My dad was in the car that day, and I watched as panic set in and the Italians started to chase the break, while up ahead Guidi took a long pull on the front of the break.

As the race developed further I could see that the group I was in was getting smaller and smaller, and, by the time we started the last lap, Johan was already away with Gianetti. I blocked as many moves as I could and chased the Italians at every opportunity, but when Michele Bartoli accelerated away on the final climb after a move from Richard Virenque and Gianni Bugno, I had to respond. I was tiring by that point and the noise from the roadside tifosi was deafening, but several things kept me going. I had the form, I knew that I still had a job to do, and my Canadian girlfriend had come over to watch me race for the first time. It sounds funny, but I really wanted to impress her. We had met earlier in the year at the Tour DuPont, and she was working for a US domestic team at the time, but she came over for the Worlds and travelled down to the race with me.

Virenque, Bartoli and I caught an earlier attack from Andrea Tafi before the line, and I gave it everything in the sprint for third. But Bartoli was too much for me and I had to settle for fourth. But I didn't mind too much. It was still the perfect day. Johan had won and Belgium had its first rainbow jersey in over a decade.

I've written so many pages of my story since then – a year later my girlfriend became my wife, and we now have a beautiful family together. My career was a happy one, and one that I can look back on with pride. Lugano has now faded into the history books, like one of the VHS tapes I used to watch, but I'm working with young riders at my Hagens Berman Axeon team, and I couldn't be happier because I'm seeing young riders start their stories, and nothing beats that.

This story was edited by Daniel Benson.