Kristoff ready to face down all comers in Spring Classics

'There is no rival I fear,' says Katusha's Norwegian speedster

This feature first appeared in Procycling magazine. To subscribe, click here.

In 2015, Alexander Kristoff topped the race winners' list with 20 victories including a sensational win at the Tour of Flanders that was born of force and guile. In the absence of an injured John Degenkolb, he's the only rider from the new generation with a Monument to his name. And despite a rocky start to the year caused by a doping positive in his Katusha team, the Norwegian insists that he will be ready to face down the challenge from all-comers in the spring races.

"There is no rival I fear," he tells us on the eve of the Tour of Qatar.

When we meet Alexander Kristoff at a transit hotel at Milan Malpensa Airport, it is not in easy circumstances. Just a few hours before, news had emerged that Eduard Vorganov, Kristoff's Katusha team-mate, had failed a dope test for meldonium, a substance added to WADA's list of banned drugs in January. As it was the squad's second doping infraction in a year, following Luca Paolini's in-competition positive for cocaine at the 2015 Tour, the team were facing a possible race ban of between 15 and 45 days.

It was the kind of news that gets interviews cancelled at very short notice and could cast a pall over a team preparing for the first race of the season, especially one that had set itself up at the beginning of the year with a brand refresh and a new attitude: this is the new Katusha – open, transparent, accessible. But as the team's Classics squad and staff filter into the Hotel Idea there is no sense of jeopardy ahead of the flight to Qatar. The lobby air is filled with happy greetings, laughter and man-hugs. It is the hubbub of a close-knit group getting ready for a long season. The bad news can wait.

We talk with the 28-year-old in a chilly, gloomy section of the lobby where the lights don't work, and we apologise for the lack of mood-lighting. "Don't worry, I'm only here to talk," he says. A brusque answer but fears the interview would be cancelled are lifted. That is until our water-testing offering – that given the circumstances, an interview is probably the last thing he wants to do – yields a thin smile from Kristoff. 'Yes, it is,' says the expression.

Just in case, we set off in the opposite direction to limber up in the foothills. We talk about the challenges of training in western Norway over winter (not so snow-affected, actually) and whether he's spent the off-season at awards galas (nominated, but didn't win).

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

When we finally loop back to the tougher Col de Vorganov, Kristoff is ready. "I had a message from my wife that Vorganov had tested positive and I was like, 'what the f-'?" he says, swallowing the swear word. "I was pretty shocked because I knew about this new rule that two positives in one year means we can be banned for up to 45 days. That means we could be missing quite a few races."

Kristoff pauses. "Maybe we are making a one-day trip out to Qatar," he adds hollowly.

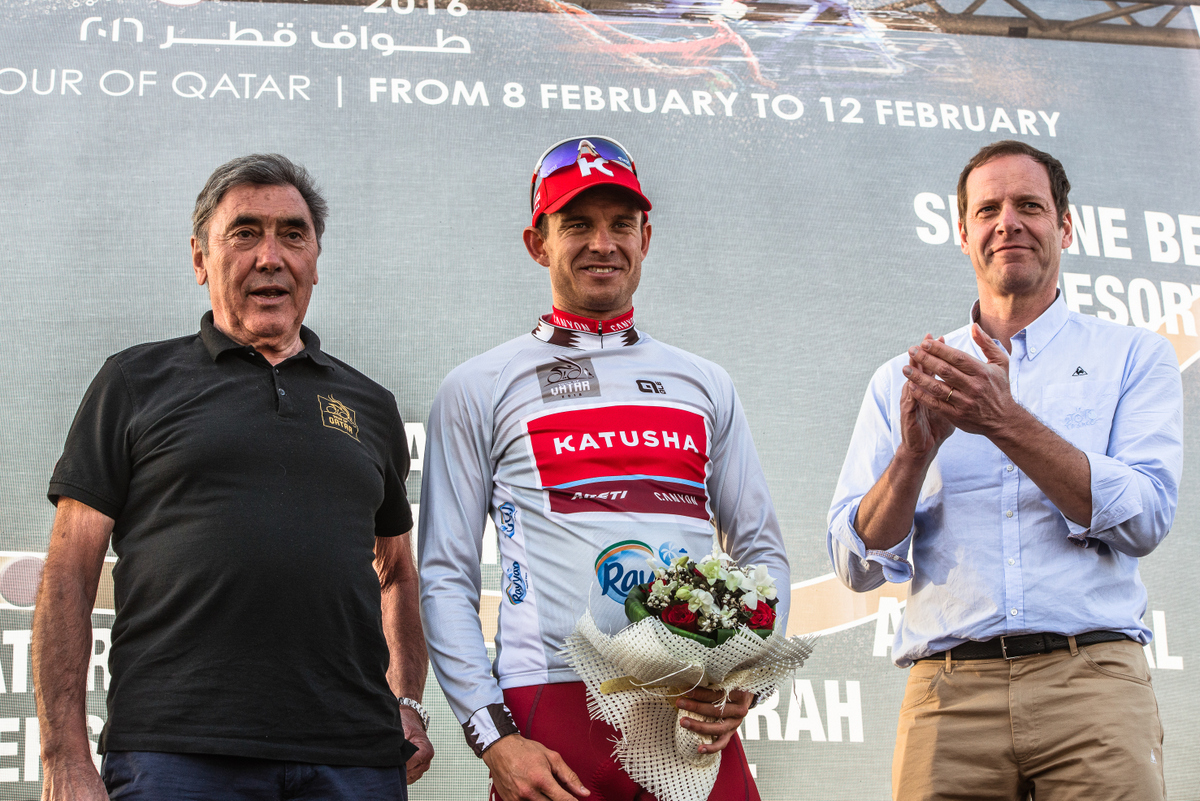

The uncertainty would last until the UCI's Licence Commission decided not to impose a ban, on the day Kristoff won stage 2 in Doha. Their reason was that Paolini's cocaine positive wasn't deemed to be for performance-enhancing purposes. But Vorganov's case still goes down as the eighth Katusha doping case since it was formed in 2009 and the first since the team turned over its new leaf. Talk about timing.

Kristoff explains that the team had been warned specifically about meldonium, the blood flow-boosting drug that Vorganov had been fallen foul of. WADA had upgraded the substance from its monitored list to its banned list after it found athletes were using it as a performance enhancer. Kristoff suggests Vorganov hadn't been listening when the team was warned about what they had to avoid.

"We had a meeting, you know," says Kristoff shortly. "This stuff that he took was allowed before January but from 1 January it was not. At the December camp we had a meeting with the medical staff and they say what is safe, what is allowed and not, and you pay attention. But he was probably not paying too much attention in this meeting," he says.

"I don't know whether he did it on purpose but he had to follow the rules and the rules are that this is not allowed. When you're taking it he is putting everybody in a bad place, risking many guys' seasons." We ask Kristoff about grey areas, and whether he's a letter or spirit of the law type of rider. "Caffeine is allowed now and I use that but it's in coffee," he says. "You can say that's a grey area and I would say I am in that grey area."

Caffeine, incidentally, has been added to WADA's monitoring list in 2016 to 'detect patterns of misuse in sport.'

"For me I think even if you don't know if there is benefit you should ban it [for the avoidance of doubt] then you don't have this grey area," he adds.

He says there are more anti-doping meetings on Katusha than there were with BMC, his former team, and admitted that is partly to try to shake off the Russian squad's sketchy reputation. The squad has a manual for riders, extracts of which were published in the statement on Vorganov, that is updated and distributed annually.

"I have not read it so carefully this year," he admits when we ask if he had flicked through it. "I read it last year and they said it was more or less the same this year. But there are rules for everything. For instance we are not allowed to drink alcohol except if the managers allow you to take a bottle of wine or something because we had an incident last year where guys from our team were drinking too much," he adds, piquing our interest, but refusing to elaborate. In December 2015, however, Katusha's doctor, Massimo Besnati, warned of a trend among young riders to mix sleeping pills and alcohol. "They drink a lot," Besnati told La Gazzetta dello Sport. Not for the first time or probably the last, Kristoff's reputation as a 'clean' rider had been leant upon for the benefit of the team. His acceptance of that responsibility demonstrates that his value to the team stretches beyond his proficiency at winning bike races.

Alexander Kristoff celebrates a win with his Katusha teammates. (TDWSport.com)

Consistency brings 'bucketload' of wins in 2015

But of course, winning bike races is what Kristoff does best. Last season they came by the bucketload. He topped the winners' list with 20 victories, four more than any other WorldTour rider, but equally as impressive was his consistency through the year. He took at least one win from every stage race he did in 2015, apart from the Tour de France where he had a slight dip in form. He managed to win about once every four race days; his real purple patch came in nine days between March 31 and April 8, when he won six times. And in the middle of that stretch, victory number 10 for the year: the Tour of Flanders, the brightest and the best for the strength and élan that he demonstrated. Other notable wins include three stages and the GC at the Three Days of De Panne, Scheldeprijs, and the GP Plouay. "Perhaps I can smell the finish line," Kristoff tells us.

There were notable near misses, too. Milan-Sanremo belonged to John Degenkolb who came around Kristoff in the last 25 metres. However, it was the Norwegian, piggy-backing on a massive effort from team-mate Paolini up and down the Poggio and along the Via Roma, who made the running. He was also edged out by André Greipel in the Vattenfall Cyclassics in August.

A stellar season then. But it has not always been like this. Unlike such contemporaries as John Degenkolb, Peter Sagan and Sep Vanmarcke, who were marked out as potential champions since their first year as professionals, Kristoff arrived with nothing like the same hype. Sure, his results with the Maxbo-Bianchi Continental team were solid and yes, he caused a stir by winning the Norwegian road race title aged 19 against Thor Hushovd. But in general, in his first four years he always seemed to be at the edge of frame in finish line photos, just a few metres back and out of focus.

Retired professional and now Team Sky DS Kurt Asle Arvesen admits he never twigged his compatriot's potential. Nor did BMC, for whom Kristoff turned professional in 2010, realise what they had. They quietly released him in 2011. He simply wasn't fast enough for them then and didn't soak up enough WorldTour points to keep things ticking over.

The American team's loss was Katusha's gain. While 2012 only yielded two victories, stage 3a at De Panne – something of a Kristoff speciality as he's won it three times now – and a Tour of Denmark stage, the step up in the quality of the podiums and top place finishes was palpable. That was thanks in part to the team's key sprinter Denis Galimzyanov failing an EPO test that April, giving Kristoff more opportunity. At the Olympic Road Race he took bronze in the bunch sprint finish behind Alexandre Vinokourov and Rigoberto Urán. And if there was a watershed moment in his career, this was it. It convinced Kristoff and his stepfather and coach Stein Ørn that they were on the right path.

During the following season, 2013, his run of results in the Classics was strong. In 11 race days between Milan-Sanremo and Paris-Roubaix, he was never out of the top 20 and was top-10 in the three Monuments. The final step came when he won Milan-Sanremo the following spring. Kristoff, the rider with the wonky helmet and the enormous thighs, was now a Monument winner and had succeeded where the many others in his bracket – Degenkolb, Sagan, Van Avermaet, Boasson Hagen and Vanmarcke – had so far failed.

Another win, this time ahead of Mark Cavendish at the 2016 Tour of Qatar. (TDWSport.com)

Humble beginnings for Katusha sprint ace

Chris Froome rode a shabby old mountain bike on the red dirt paths in the Rift Valley and Ivan Basso crested the Stelvio aged eight in the slipstream of his father. Every top rider has a pleasant, homely foundation story. Alexander Kristoff's is just as humble and memorable. When he was 13 or 14, local organisers bent rules so that he could race with veterans – a privilege usually reserved for 16-year-olds. "The organisers said it was okay because I was quite good at that age," he remembers. "I raced against the best amateurs and veterans – old people who were really fighting hard for victory. The races were long, maybe 120km, when the maximum I should have been doing was about 50km.

"So I really learned to suffer hard in way longer races than others my age were doing – and at higher speeds. I think from this I learned how to race professionally and save energy."

He believes the experiences were formative and that they gave him a gift he retains today: a capacity to endure better than rivals. "I started young and I learned to suffer; I was prepared to suffer more."

Yet that's not the whole picture. What is equally impressive is Kristoff's clinical finishing. Take his Flanders victory last year. He had jumped out of the peloton with 27km to go, with only Niki Terpstra for company. The Paterberg loomed and one deep, asphyxiating effort, to keep the Etixx-Quick Step rider blowing hard and unable to attack, left victory in reach.

From the top of the Paterberg to the finish line in Oudennaarde, it's 13.2km. Behind is a group of chasers at 20 seconds. Luckily the group is a bit headless but still there is no room for manoeuvre and Kristoff needs Terpstra badly.

According to the race reports afterwards, to cajole Terpstra into continuing to collaborate he said, "Come on, it's good to be second too."

What a line. What front. Everything we need to know about how that race would end is in that sentence. Kristoff knew that beating Terpstra in the sprint would be a formality, and yet he still managed to coax the Dutchman into helping him get there.

Kristoff did everything right as he beat Niki Terpstra in the 2015 Tour of Flanders.

Time constraints that go with success change approach to races

After he won two Tour stages in 2014 we were told Kristoff used to prepare for races with mental visualisation, tasking himself to imagine how the race might unfold. He was a conscientious student of racing, too, scouring videos for the tics and flaws of rivals. But as his stature has grown and the demands upon his time have mushroomed, that diligence has melted away. Now Kristoff's objective is to switch off from cut and thrust of the day job as quickly as possible.

"I've stopped watching races now," he says. "Sure, I sometimes watch the sprints to study the last 15 minutes to see what the other guys do. But I get a little bored."

Talk to Kristoff for long and the picture emerges of someone who is quite disengaged from the sport. The head of his Belgian fanclub, Dirk Biliau, told us that Kristoff reminded him of the 1985 Flanders and 1987 Roubaix winner, Eric Vandaerarden. "Who?" says Kristoff. "Never heard of him. That was before I was born. I know who Eddy Merckx was and some of the biggest guys but I don't really pay attention."

Instead, the Norwegian indulges in computer games to pass the time. "Before, when I was younger I liked shooting games. Now I like driving games and normally I have my computer and an Xbox control, so I play Fifa a lot."

Last year, at the Park Hotel in Kortrijk, Katusha's regular home from home during the Classics, Kristoff embarked on an assault on Grand Theft Auto V and completed it in a week, he tells us, looking half satisfied, half guilty. Later, we learned why: the game can take anything between 45 and 65 hours to complete. He only took 30 hours to complete Paris-Nice last year.

We'll admit to meeting Kristoff with preconceived ideas of who we might find. The asceticism and taste for suffering squares well with his reputation for being a rider who has worked steadily towards the top of the tree. In public, Kristoff is the model modern pro: modest, sanguine, positive and focused. But it's the other side of Kristoff - the blokey traits and an earthy take-it-or-leave-it philosophy - that's more likeable. Throughout the interview, riders and staff had quietly and politely interrupted the interview to greet their leader. As they came over, he half rose on those teak-like thighs to greet them and it was clear he was happy to see them, yet was trapped by obligation. But he quickly returned to listen earnestly to the next question.

Kristoff's more accessible than his team-mate Ilnur Zakarin and more bankable than Joaquim Rodríguez. He is also, at the age of 28, coming to the zenith of his powers as a professional cyclist. That alone makes Katusha reliant on him - with 40 wins last year, the team were third in the win list, but half their total came from Kristoff. However, they also need his help to distance themselves from the riders who have tested positive while on their books. As Katusha try to unscramble the mess of the fresh start Vorganov has left them with, at least they know they can rely on Alexander Kristoff, whatever role they deploy him in: surgical race winner or likeable, approachable team ambassador.

This article appears in the current edition of Procycling magazine, February 2016. To subscribe click here.

Sam started as a trainee reporter on daily newspapers in the UK before moving to South Africa where he contributed to national cycling magazine Ride for three years. After moving back to the UK he joined Procycling as a staff writer in November 2010.