In the American Pacific Northwest, summers mean long warm days. It rarely gets too hot and, despite the reputation that Seattle and Portland both have, it rarely rains. As an endurance rider who doesn't race, I take advantage of this time by pushing my rides longer and longer and eking out every last moment of the day. Riding from sunup to sundown through some of the most beautiful landscapes in the world makes it easy to develop fitness. Then, right around the beginning of September, it all comes to an end.

It feels like the days get suddenly shorter and the rain, always cold, can feel relentless. It's easy to fall into a period of mourning and as the winter drags on, depression can even set in. Over the years one of the ways I've taken to combating this is to keep my training consistent by turning to indoor training.

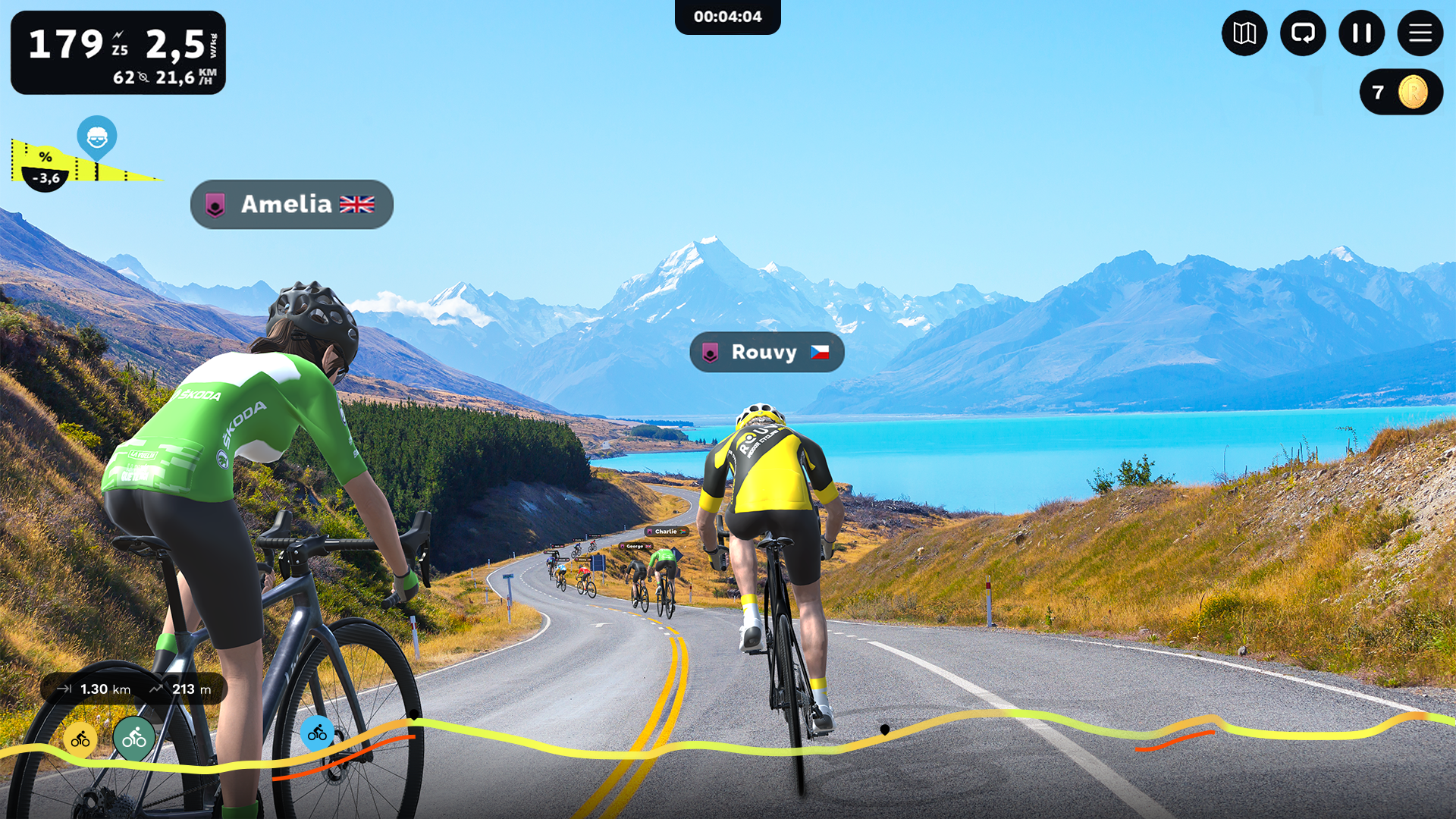

When I was younger, indoor training often meant intervals. As I've aged, and spent more time cycling, I've found that while interval training has its place, and benefits, I can't sustain my joy for cycling with intervals alone. Sometimes I need to ride in a way that feels similar to my outdoor rides and one of the ways I've done that is with Rouvy.

There's something I've found though. Even though indoor cycling can help your mental health, it isn't the same as outdoors. Of course anyone who's done any indoor riding will tell you that but I like to understand the why of things. Indoor riding feels more difficult, why is that? Certainly there are a number of reasons but I set out to see what might be making it harder to ride indoors and if there was anything I could do to make it easier and more pleasant, here's what I found.

Indoor heat and the effects of heat acclimation

One of the first clues to what I think is an under-appreciated challenge with indoor riding came to me because of my Garmin cycling computer. What I mean is that when I ride outside during the summer the Garmin 1040 Solar I use has a data field it shows at the end of each ride called heat acclimation. "Heat acclimation shows as a scale of 0 – 100% of how well you are adjusting to heat during training" and according to Garmin "full acclimation takes a minimum of four training days."

The reason this matters is that there's a performance advantage to heat acclimation. According to "Prolonged Heat Acclimation and Aerobic Performance in Endurance Trained Athletes" published in 2019 in Frontiers in Physiology, "Acclimation for heat was verified by lower sweat sodium [Na+], reduced steady-state heart rate and improved submaximal exercise endurance in the heat." In other words, when we acclimate to heat we are able to exercise at a lower heart rate. A lower rate means an easier time so that's significant.

Despite that, I haven't actually ever spent much time considering heat acclimation. As the days have gotten shorter though, I noticed something. At the end of my outdoor rides, the heat acclimation data stopped showing up. When looking into it I found that Garmin only shows that data when the temperature is above 22C / 72F.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

This, obviously, means the temperature is falling outdoors but there's another side of that. The outdoor temperature may be falling but my indoor temperature isn't. In the laundry room where I ride indoors the temperature is often close to 27C / 80F.

If you connect all the dots here there's an obvious problem. As the temperature outside cools, I'm naturally losing my heat acclimation. At the same time, I'm mixing indoor rides into my general exercise routine and asking my body to perform in the heat without acclimation. It's natural that indoor workouts feel more difficult.

How the body deals with increased heat during exercise

Heat acclimation is actually only one part of the problem and it happens to be a part of the problem that I don't have an easy way to quantify. Although the Garmin 1040 Solar has the ability to directly measure temperature, that data isn't part of the heat acclimation score. According to Garmin, "your device has to be connected to your phone to get accurate weather data in order for this functionality to work properly. Even if your device is able to directly measure temperature, heat acclimation is always calculated based on weather." Meaning, that I needed another way to understand the physiological effects of riding indoors in the heat.

Instead of looking at the somewhat nebulous concept of heat acclimation, I pivoted and looked at the physiological effects of training in heat. Although I knew that I should be seeing a higher heart rate, that seems like a difficult thing to measure given the variety of riding I take on both indoors and out. There are other effects though.

According to "Physiological Responses to Exercise in the Heat" published in 1993 by the National Academies Press as part of "Nutritional Needs in Hot Environments," there are two primary ways the human body tries to regulate heat. "To regulate body temperature, heat gain and loss are controlled by the autonomic nervous system's alteration of (a) heat flow from the core to the skin via the blood and (b) sweating." Which I read as meaning that in addition to higher heart rate, I should also be experiencing more sweating.

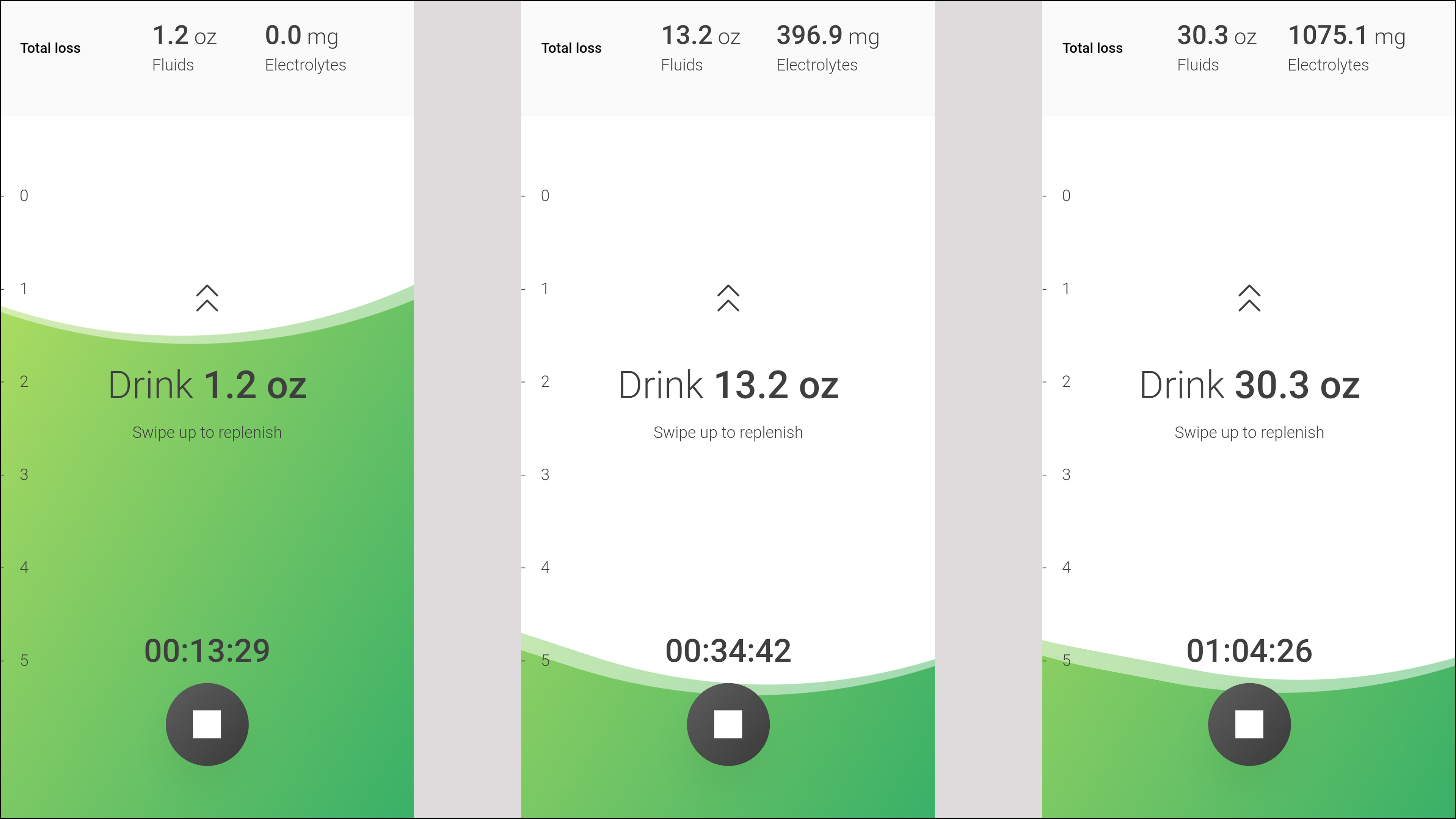

This will, again, be patently obvious to anyone who has ever ridden indoors before. I'm pointing this out though because I've been testing a product called the Nix Sweat Sensor for the last few months. The Nix Sweat Sensor is an objective way to measure exactly how much I'm sweating indoors and what that might mean for my ability to perform and how hard indoor riding feels.

The Nix Sweat Sensor, sweat loss, and dehydration

The Nix Hydration Biosensor is a system that consists of disposable patches, a sensor pod, and an app. When you are ready to ride just place a fresh patch on your upper arm, attach the USB-C rechargeable transmitter pod to the patch, and use BLE to connect the pod to the app on your phone. During exercise, the patch collects your sweat and transmits the data to your smartphone for a real time visualisation of your fluid loss. It's possible to either use your phone for notifications or connect to an Apple Watch, Garmin Watch, or Garmin bike computer for notifications.

In my time using it, what was most interesting was to see how my body worked. Although I tried using the data in real time, I found I wasn't very good at responding like that and it actually didn't matter much. It didn't matter because what the data showed me is that my body, and probably yours, responds in a very predictable way. The app allows you to show averages for specific sets of workouts and when riding outdoors I averaged a loss of 14 oz/hr of fluid with an electrolyte loss of 584 mg/hr. If I instead look at only indoor rides though those numbers jump to 30.4 oz/hr and 1278 mg/hr.

It should be obvious that those numbers are drastically different but I also make it worse. Since most indoor rides I do are about an hour, I often don't drink anything. Given how bad that looked, I was curious what it might actually mean for my performance so I reached out to Nix to find out.

I started by asking, how fast will performance start to drop off if you don't hydrate during a ride? The response I got from CEO Meredith Cass was, "the rule of thumb on this is that you begin to lose performance at the 2% dehydration threshold, meaning once you’ve lost 2% of your body mass, your performance significantly drops off (research shows 29% performance loss at this point). Somebody who is 150lbs dehydrates to 2% dehydration at approximately three pounds/48 ounces of fluid lost."

Initially I thought that meant I was fine not drinking given that I don't lose 2% of body mass in an hour. That's not actually true though and Cass goes on to give a bit more insight saying "while you’ll lose a significant amount of performance at 2% dehydration, it's not a cliff. You’re gradually losing performance before this threshold." Cass also explains a bit about what type of performance fall-off you can expect and, at least to me, it sounds very typical.

To get even a bit more info on what I might expect to start experiencing, I then followed up by asking what type of performance impact I should be looking for and, as Cass explains, I think indoor riders will recognize it.

According to Cass, as our bodies dehydrate, "the fluid deficit is coming from the blood volume so it means the body is going to have a harder time getting oxygen to all the parts of the body that demand it. The body will pull back from the muscles, for example, because that's in favor of the vital organs – heart, lungs, brain - since those systems need oxygen even more than your muscles. This means you're basically depriving your muscles of oxygen and you will start to feel really fatigued in the body. To compensate, your heart rate and your respiratory rate will increase which could be described as cardiorespiratory stress. You’ll start to feel more fatigued as your body is working harder to try to keep up."

Cass also jumps into a little more detail about what athletes can expect even if they aren't getting to a full 2% body weight loss. As she expands on that earlier discussion she says that while "the research has established that if you're 2% dehydrated you're already in a 29% performance impairment band and it worsens from there. This is a massive performance loss, much more significant than just ‘eking’ out a performance edge. It literally means that someone is moving 29% slower than if they were properly hydrated. While sports performance scientists focus on this 2% dehydration/29% performance loss threshold, this isn’t a cliff. You are gradually losing performance before hitting this threshold and it stands to reason that there would be some physical impairment, like fatigue, happening as you get closer to this point."

It's also worth mentioning at this point that while Cass is speaking in generalities, I'm comparing it to my specific data. I tend to lose an average of 30oz an hour riding inside but everyone is different and every setup is different. I'm reporting my data because that's what I have. Cass is careful to say that this data "is so variable among different physiologies and environments, it’s important to use your own sweat data to create the best hydration strategy for your training."

There are a couple of things we can be sure of though. When riding indoors during times when our body isn't heat adapted we will experience a higher heart rate because of the effect of the heat indoors. At the same time we can expect to experience higher liquid loss because of sweat and that will lead to hydration related performance loss. If you think it feels harder to ride inside, that's because it is. Now the question is, what can you do about it?

How to ride indoors more comfortably

I've already talked about how the primary response of the body to heat is to move heat through the blood to the skin then sweat to take advantage of evaporative cooling on the skin. Even in hot weather, our bodies have a highly efficient system to stay cool. If you want to make riding indoors easier, and more pleasant, then what you have to look at is boosting the natural systems our bodies already have.

The first place that starts is with hydration. I've spent time with the Nix sensor system quantifying how much liquid I'm losing indoors and it's a lot. CEO Meredith Cass helped explain what that meant for performance, and by extension perceived difficulty, but it's not only water our bodies lose. According to Cass, "it’s predominantly electrolytes – sodium and chloride make up equal parts of this, at 47.4% each. This might be a big surprise for people, as we generally see people focused on the electrolyte sodium, but not chloride. Additionally, there is 4.7% potassium, then calcium and magnesium represent .2%. Then of course there are elements like hormones, glycogen, glucose, lactate, etc. but the electrolyte component is generally what is most relevant for endurance athletes."

That means you are going to want to turn to something more than just water when trying to replace what you lose riding indoors. We've got an article covering nutrition for indoor cycling with a variety of amazing advice. In that article you will find a section on hydration but there's also a wide range of information about food.

In addition to that, I've spent years doing a significant amount of training indoors. Personally, I tend to do better with liquid based nutrition. I also tend to prefer things to be simpler and off the shelf products are where I find success. For rides in the 3-5 hour range (yes, I ride for that long indoors) my go to product is SIS beta fuel. It's high in calories and I find it easy to drink but it is very sweet. For those that prefer something less sweet, another great option is to choose one of the products I grab for shorter rides and add Osmo power fuel. Osmo power fuel is essentially neutral flavoured carbs you can add to whatever drink mix you like.

In terms of the products I like for shorter rides, typically in the one-hour range, Osmo also has an option called Osmo active hydration. Other products I like for shorter rides, and times I want something less intense than SIS Beta, are First Endurance hydration mix, Tailwind Endurance fuel, and Skratch Hydration drink mix. Each one has a bit different taste but Skratch and Osmo offer a bit less calories per scoop if you are riding shorter. I would also say that Skratch is the least sweet option.

Once you've tackled hydration, the next piece of the puzzle you will want to look at is clothing. While it's common to use an old kit, I prefer to look for hot weather and indoor specific options. We have our article covering the best indoor cycling clothing and I've personally tested options from both Castelli and Assos. The Assos Equipe RSR Bib Shorts Superléger S9 and the SS Skinlayer Superléger is what I grab most often.

Another piece to figure out is air movement. Arguably this is actually more important than clothing or hydration, especially for shorter rides. It makes a huge difference not only in perceived effort but even if you manage to struggle through being a bit dehydrated, and with a kit that is slightly warmer, your body can't effectively cool down without a good fan moving air. To that end, I can't recommend any better fan than the Wahoo Kickr Headwind.

This year though, I've actually added a second fan. The Headwind is my favourite but my space is so small I can't get it right where I think the ideal spot is. I've now supplemented it with a Vornado fan connected to a smart plug I named "The Pain." When things get extra intense, I can now yell "Hey Google, turn on the pain" and it helps cool me down as well as always bringing a smile to my face.

Even with all the right gear though, indoor riding can be very difficult if you don't keep your mind occupied. There are a ton of great options to make that happen. The biggest name in the space is certainly Zwift but I'll be throwing Rouvy into the mix this year as well. Elevation profiles for real locations somehow feel different and different can be a powerful motivator as winter drags on. Whatever ends up working for you, make sure you consider it. Staring at a wall will only make your training feel harder.

Josh hails from the Pacific Northwest of the United States but would prefer riding through the desert than the rain. He will happily talk for hours about the minutiae of cycling tech but also has an understanding that most people just want things to work. He is a road cyclist at heart and doesn't care much if those roads are paved, dirt, or digital. Although he rarely races, if you ask him to ride from sunrise to sunset the answer will be yes.

Height: 5'9"

Weight: 140 lb.

Rides: Salsa Warbird, Cannondale CAAD9, Enve Melee, Look 795 Blade RS, Priority Continuum Onyx