Just how fast would cycling great Beryl Burton be today?

New book by Jeremy Wilson unravels enigma of the cycling great, including how modern aerodynamic advances would transform her times

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Yorkshire Dales are a sparse windswept place, filled with heather, small towns, and ribbon-like roads that twist over hundreds of hills and valleys.

It was on these roads that Beryl Burton achieved many of her greatest accomplishments, trained for many more, and ultimately died at the age of 58.

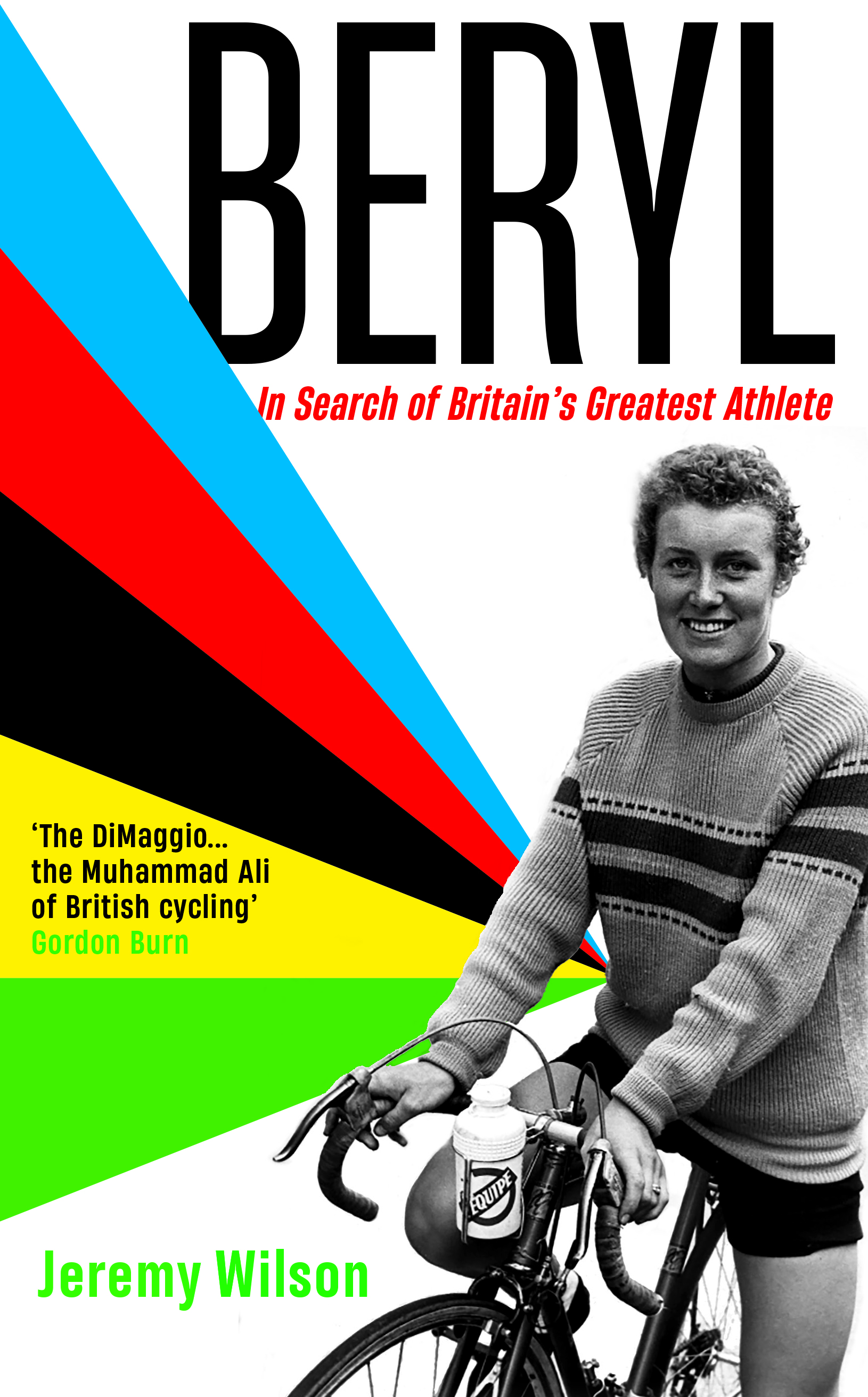

The gravity of her achievements has become somewhat obscured in the years since her death but are now immortalised in a new biography by sports journalist Jeremy Wilson, simply titled Beryl: In Search of Britain’s Greatest Athlete.

For more than twenty years, from 1957-1980, Burton remained at the pinnacle of her sport. In that time, she won seven world championship gold medals, 25 consecutive British Best All-Rounder titles – an annual competition that ranks riders by their average speeds in individual time trials over 25, 50 and 100 miles – and became the only woman ever to break an endurance men’s record when she broke the British men’s 12 hour time-trial record.

“I didn’t start out with anything more than the memory of this person who was extraordinary in my mind but I didn’t really know much more,” Wilson says. “I hadn’t quite pieced together how she had died, the early trauma, and all the other parts of her story.”

Burton’s achievements on the bike were intimately tied to, and often indistinguishable from, her life off it. Cycling was her sport, hobby, social life and means of transport. However, in an era when professional cycling did not really exist – especially for women – it was not a job.

Burton worked on a rhubarb farm, cleaned houses, and worked on the biscuit counter at the local Co-op supermarket alongside her record-breaking exploits.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“I don’t think people who knew her outside of cycling necessarily knew she was a great cyclist…she wasn’t showy,” Wilson says.

This humility belied a ruthless streak that marked Burton as a great competitor. The prizes and medals she won were relatively unimportant; it was the simple act of winning that seemed to motivate her. Wilson spends much of his book explaining the origins of that drive, delving into theories that link childhood trauma to exceptional athletic achievement.

“I spoke to a journalist called Sue Mott who interviewed Beryl in the early 80s … and she said that she had never met a sportsperson who was so driven and focused as Beryl even having known those sorts of people as well [like Steve Redgrave and Andy Murray],” he says.

This single-minded focus culminated at the 1976 British national road race championships when Burton was defeated by her daughter, Denise, and infamously refused to acknowledge her on the podium.

In interviews with Denise and the rest of Burton’s family, her friends, rivals, and fellow sports superstars such as AP McCoy, Wilson begins to unravel each strand of Burton’s personality.

‘She just kept going and going’

As her powers declined and her dominance waned, Burton refused to retire. In 1984, when Burton was 47-years-old, the first women’s Tour de France was held and women were allowed to compete in the Olympics for the first time. She lobbied for a place in both teams but was ultimately not selected.

“That inability to stop wanting to be the best - part of me loves it and part of it is quite tragic as well. It’s also quite moving because she just was who she was,” Wilson says. “There was a sort of authenticity to it. She just kept going and kept going because she wanted to win and didn’t really care about the medical advice.”

Burton eventually died of a heart attack while riding her bike in 1993. In the years since, women’s cycling has changed dramatically, as has Burton’s place within it.

Wilson’s book, along with a play written by Maxine Peake in 2012 and William Fotheringham’s 2019 biography, aims to relocate Burton from the relative wilderness to a place among the greatest British athletes of all time.

“I think a lot of these things get judged on Olympics and Tour de Frances and obviously women weren’t allowed in those events so it’s a bit harsh to judge her on two events she wasn’t allowed to ride in,” Wilson says.

“If we…say what would she have done, even being quite conservative with it, I’m pretty sure she would have surpassed anybody else.”

The following is an extract adapted from Beryl: In Search of Britain’s Greatest Athlete by Jeremy Wilson which is now available in all good bookstores.

As Beryl Burton’s sparkling old handmade steel TI-Raleigh bike was released and then carefully lifted from a mount, a series of engraved letters and numbers – ‘BB.1.81’ – briefly became visible on the bottom bracket. The exact machine on which Beryl raced during much of the 1980s, and which is photographed on the front cover of her autobiography, had just completed its most vigorous workout for more than thirty years. ‘People will struggle to believe this,’ muttered Dr Xavier Disley, one of the world’s leading experts on aerodynamics, as he clicked through various tables, graphs and spreadsheets and began to mentally compute the information in front of him. We were inside a wind tunnel at the Silverstone motor-racing circuit, and the objective for the day had been to finally resolve one of British cycling’s classic café stop debates.

Just how fast would Beryl Burton be today? Her record times might have been finally broken, but would modern aerodynamic kit put her straight back on top of the pile? Or would improvements in training and sports science inevitably still leave her behind? When you really stop to think about it, the idea that any athlete could overcome a handicap of more than 50 years is outlandish. Imagine plonking Sir Gareth Edwards, all 5ft 8in. and 13 stone of him, from the 1970s into an international rugby union match today. Or placing Billie Jean King in a time machine, letting her adjust to a modern tennis racket for a few weeks and then expecting her to hold her own on Centre Court at Wimbledon against Serena Williams. And just consider other endurance sports like athletics and swimming. Technological advancements are minimal compared with cycling, and yet the purely human improvement through the decades is vast. But was any athlete ever further ahead of their time than Beryl Burton? She was the holder of the national 12-hour record for half a century, setting a distance which originally bettered the men. She was a national champion more than 100 times in disciplines ranging from the 3,000m pursuit to the 100-mile time trial. And she was, arguably, the greatest female cyclist in history.

The sense that aerodynamics have been a complete game-changer in modern time trialling is repeatedly confirmed by anyone with experience across the eras. ‘It’s another leg,’ said Dr Jamie Pringle, who worked as the head of science and technical development at the Boardman Performance Centre. Chris Boardman himself agrees and, having been head ‘secret squirrel’ for British Cycling between 2004 and 2012, became an authority on aerodynamics. ‘We found that expenditure to go the same speed can differ enormously,’ he said. ‘It’s mostly about body position. Efficiency has changed because of knowledge and technology.’

Xavier Disley owns the AeroCoach company, which works with elite and amateur riders on aerodynamics, and was confident that he could calculate accurate projected ‘Beryl’ times provided that a set of conditions was met. We must source an equivalent bike and clothing from Beryl’s era and a rider of comparable size and aerodynamic potential. Information on the precise courses on which Beryl set her records would also be invaluable.

A phone call to Malcolm Cowgill, secretary of the Morley Cycling Club for whom Beryl proudly rode between 1953 and 1996, and a classic pale blue jersey had soon arrived on loan from Yorkshire. Notes about the courses, and their unique indentifying codes, had been handwritten by Beryl and preserved by her now 92-year-old husband Charlie. The frame builder Dave Marsh collects vintage bikes and, among those on display at his Universal Cycle Centre in Maltby, is Beryl’s TI-Raleigh, which was custom-built to a size of 20.5 in. (52cm) in 1981. With its classic Campagnolo Record components and glossy red, yellow and black paintwork on a steel Reynolds 753 frame, Marsh has maintained the TI-Raleigh to an immaculate standard and granted permission for its day out to Silverstone.

That left finding a rider to be Beryl Burton for the day. Disley stressed the need for an experienced cyclist who could consistently hold Beryl’s low ‘tucked’ position and assume a similarly optimal position on a modern time trial bike. Jessica Rhodes-Jones, the UCI’s world amateur time trial champion in 2017 and 2021, immediately agreed. Clothing, said Disley, accounts for around a quarter of the aerodynamic improvement, and he was also keen to iron out any discrepancies that could be caused by Rhodes-Jones’s long hair. It meant sourcing a short curly wig which was trimmed to the classic Burton look. In sizing up Beryl’s original machine, Disley could instantly see that the Burtons were just as determined to maximise every perceived advantage as any rider today. Charlie had wrapped the handlebar tape so that it only covered the drops. There was just one front chainring – a huge 56-tooth ring – and thus only one gear lever on the side of the downtube, with a minimal 13–17 back cassette. Track tubulars had been glued onto the wheels rims. Even the brake hoods and water bottle holder had been removed to save extra grams.

Disley’s methodology was fairly straightforward. By mounting a bike inside the wind tunnel and then blowing air through the area as a rider pedals, he can calculate how efficiently a bike and rider are moving, which is known as their drag coefficient (CdA). Disley specifically needed to know Beryl’s CdA once Rhodes-Jones had replicated her positions and fired up the two bikes to a speed of 45kph (which equates to 21min. 30sec. for 10 miles).

The TI-Raleigh was first up. Rhodes-Jones had used photographs and videos to study Beryl’s pedalling style and position. With Disley assessing everything on two large screens – one showing the rider’s cycling position from three angles and another which displayed a moving line graph and calculations for wind speed, drag, wheel power, cadence, wheel speed and side-to-side movement – he finally signalled that he had the required information. After a short break to rotate the bikes and for Rhodes-Jones to change into her usual aero helmet, shoes, drag-resistant skinsuit and long socks, Disley then conducted the same test on her Cervelo P5 time trial bike. The first obvious contrast was the noise. Whereas Beryl’s old bike just made the quiet whir of a perfectly oiled and maintained machine, disc wheels create an incessant hum. Rhodes-Jones also noted major differences in the respective feel. ‘I felt very much that I was pedalling with the toes and front ball of my foot with the old leather shoes,’ she said. The biggest difference, though, was in how the aero handlebars provide a stable base across the upper body. ‘The Beryl bike was overwhelmingly less comfortable,’ she said. ‘You can basically lie forward on a modern time trial bike whereas Beryl would be really tensing her triceps and core. How she sat in that position for 12 hours I just don’t know.’

And so to the main question. What times would Beryl have set, making the same effort, on modern kit? A normal road bike usually produces a CdA (the measure of aerodynamic drag) of around 0.30m^2 but, by emulating Beryl’s crouched position, Rhodes-Jones reduced this on the TI-Raleigh to a lowest sustained figure of 0.2430m^2. This dipped to 0.2258m^2 after simply changing into the modern clothing and then down to 0.1781m^2 once the same speed of 45kph had been reached on the Cervelo P5. The wind-tunnel test also provided a power reading for the required watts to achieve the speeds and times of Beryl’s various records on the TI-Raleigh. The final step was to then combine these power projections with the much lower CdA drag coefficient that was produced while riding the Cervelo P5.

It all produced the following astonishing results:

| Distance | Beryl’s previous record | Beryl, new time on modern set-up | Current record | Difference to current record |

| 10 miles | 21min. 25sec. (29-4-73) | 19min. 29 sec. | 18min. 36sec. Hayley Simmonds | Beryl down by 53sec. (but her record would have stood until 2016) |

| 25 miles | 53min. 21sec. (17-6-76) | 47min. 52sec. | 49min. 28sec. Hayley Simmonds | Beryl still up by 1min. 36sec. (after 46 years) |

| 50 miles | 1hr 51min. 30sec. (25-7-76) | 1hr 41min. 06sec. | 1hr 42min. 20sec. Hayley Simmonds | Beryl still up by 1min. 14sec. (after 56 years) |

| 100 miles | 3hrs 55min. 05sec. (4-8-68) | 3hs 33min. 16sec. | 3hrs 42min. 03sec. Alice Lethbridge | Beryl still up by 8min. 47sec. (after 54 years) |

| 12 hours | 277.25 miles (17-9-67) | 305.23 miles | 290.07 miles Alice Lethbridge | Beryl still up by 15.16 miles (after 55 years) |

As the table shows, Beryl remains decisively faster over her three core distances – 25, 50 and 100 miles – than any rider has achieved in the decades since. At the shorter 10-mile distance, which only became a national championship for women in 1978, Hayley Simmonds surpassed her adjusted time in 2016. Beryl’s projected 12-hour performance remains jaw-dropping and her ongoing dominance over 100 miles further amplifies her exceptional strength in endurance events. Most impressive of all, however, is surely the versatility over such a spread of distances. For she is effectively racing two groups of riders in these comparisons. You have an outstanding group of short- and middle-distance time-trialling champions and record holders like Simmonds, Yvonne McGregor, Dame Sarah Storey and Wendy Houvenaghel but then also some excellent new long-distance specialists at 100 miles and above, led by Alice Lethbridge, Joanna Patterson and Christina Murray. Few riders now challenge across so many disciplines, let alone with such outstanding success. And then there are Beryl’s seven world titles in the track pursuit and road race, which are quite distinct disciplines again.

Having answered our question so precisely, a follow-up call with Xavier Disley was somehow even more striking. ‘I just can’t think of another sportsperson whose athletic feats have remained so measurably outstanding,’ he said. ‘I think we have made good estimates – and the fact that she broke a male competition record is, for me, the stick in the sand which cements it. Some ultra endurance events which go on for days do increasingly favour women, but 12 hours is not the same. It’s more like the Ironman in triathlon, and a female beating all the men would be completely bonkers. What Beryl did is so far out there that you would be very hard-pressed to find any other instance of that ever happening.’

Disley also stressed that our wind-tunnel results can only demonstrate the difference that aerodynamic bike technology and clothing have made without factoring more intangible advances in the knowledge of training, nutrition, psychology and recovery. Course conditions, notably road surfaces and traffic, throw up further possible advantages that can never be precisely measured. The bottom line, though, is surely clear. Technology has progressed beyond the records that the great Beryl Burton set. Other athletes, even more than half a century later, have not.

Adapted from Beryl: In Search of Britain’s Greatest Athlete

Issy Ronald has just graduated from the London School of Economics where she studied for an undergraduate and masters degree in History and International Relations. Since doing an internship at Procycling magazine, she has written reports for races like the Tour of Britain, Bretagne Classic and World Championships, as well as news items, recaps of the general classification at the Grand Tours and some features for Cyclingnews. Away from cycling, she enjoys reading, attempting to bake, going to the theatre and watching a probably unhealthy amount of live sport.