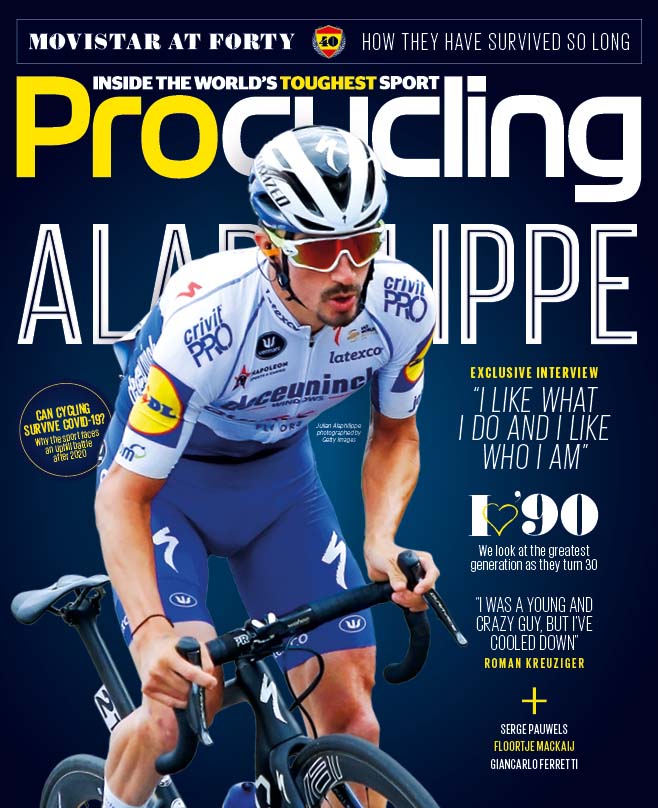

Julian Alaphilippe: Rage against the machine

Procycling interviews Julian Alaphilippe ahead of the 2020 season restart

Julian Alaphilippe is the biggest star in world cycling, with charisma to match his all-round ability and results. Procycling met the irrepressible Frenchman for a chat this summer, a few months before he became the 2020 road world champion.

This article was taken from Procycling magazine issue 269, June 2020.

Subscribe to Procycling magazine for just £5 for the first five issues.

Just when it seemed all creativity, character and variety had been crushed out of the Tour de France by science, numbers and negative tactics, Julian Alaphilippe arrived and blew through the race like a whirling dervish. The Frenchman coloured in an event which had greyed to monochrome, and it’s symbolic that in the last two editions, he’s spent more time wearing either the polka-dot or yellow jersey than his team kit.

His effervescent confidence and aggressive riding are compelling to fans and media, and he hasn’t developed the same ennui that has descended on Peter Sagan’s interactions with the press, or the studied diffidence of Vincenzo Nibali. These two riders have excited fans with their panache, but sometimes give the impression off the bike that it’s all a bit of a grind.

I remember grabbing Alaphilippe for a word at the second rest day of the 2018 Tour, when he was already one stage win to the good and looking like a fairly safe winner of the polka dot jersey. He was dutifully sipping from a can of Maes 0.0%, the non-alcoholic beer brand which his Deceuninck team had announced as a sponsor that day, and I suggested to him that being a French rider doing well in his home race must bring an increased level of attention. How was the pressure affecting him, I wanted to know. The French word for ‘pressure’ and ‘beer on tap’ is the same: pression. Without missing a beat, he held up his can and informed me the ‘pression’ was delicious.

Julian Alaphilippe wins world title at Imola World Championships

Julian Alaphilippe set to miss La Flèche Wallonne after Worlds win

Lefevere on Alaphilippe's Worlds victory: 'Are you proud of me?' he kept asking me – and of course I am

Julian Alaphilippe reaches the summit at the World Championships

Alaphilippe’s 2019 Tour, in which he wore the yellow jersey deep into the final week, and even looked like a possible winner before cold reality sapped the zing from his legs in the Alps, got a lot of people very excited. Could the artist take the Tour back from the scientists? Could he beat the Ineos machine?

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The narrative built slowly. Nobody was very surprised when he won the punchy stage to Épernay, though he performed a minor miracle in taking the yellow jersey that day. But he rode above expectations to finish with, and even ahead of the big GC favourites on La Planche des Belles Filles three days later. We rationalised that simply as a puncheur doing well on a steep finishing climb.

By the time he escaped with Thibaut Pinot on the road to Saint-Étienne to put another 20 seconds into their rivals, L’Équipe had started running a colour-coded risk assessment chart to speculate how long he could keep the yellow jersey. They coloured the Brioude, Albi and Toulouse stages in green - his lead of just over a minute would surely be safe there.

The Bagnères-de-Bigorre stage in the Pyrenees was coloured orange - maybe the Hourquette d’Ancizan climb would be too much for him. The Pau time trial and Tourmalet were coloured red. The idea of working out whether he could keep his lead the day after the Tourmalet to Prat d’Albis was such an inconceivable question that they didn’t even include that stage. In the end, he did well enough that he could swoop down the descent of the Col du Galibier on the first day in the high Alps, catch the leading group, and leave himself with two mountain stages to survive to win the Tour. Of course people got excited.

However, before the sport and results are taken into account, the most important thing about Julian Alaphilippe is that he is fully, demonstrably, incontrovertibly himself. This elemental truth underpins the rest, though he is at a loss to explain where it comes from. It’s just always been that way.

“I’m the same person I was a year, five years or even 10 years ago,” he tells me on a Skype call from his base in Andorra. “Erm, I’ve grown a moustache… but nothing has changed in my way of being, my way of living, my way of working, and the way I see life. As a rider, it’s more difficult to get into escapes now – some teams are really watching me.

“But I work very hard and I know what I want. I’ve been like that since I was little, in spite of my results or what has happened these last two or three seasons. I like what I do and I like who I am. The best question would be: why would I change? I think I’ve never really changed.”

What has changed, however, is our reaction to him. In his early years, before he learned how to win, he was perennially consistent in big races without ever quite making the breakthrough. His second places to Alejandro Valverde in the 2015 Liège-Bastogne-Liège and 2016 Flèche Wallonne, and to Peter Sagan in stage 2 of the 2016 Tour de France were followed by handlebar-banging frustration. He looked like his ability hadn’t quite caught up with his impetuosity and ambition. Now, we’re talking about a rider who could conceivably win at least four monuments, and maybe, one day, even the Tour.

All you need to know about Julian Alaphilippe is contained in his attack to Épernay in the heart of champagne country in last year’s Tour. He could quite easily have left it to the final climb to the finish line, which would have still given him a stage win, but no chance of the yellow jersey - he’d gone into the stage 31 seconds down on overall leader Mike Teunissen, but more significantly 21 seconds behind Teunissen’s team-mate Wout Van Aert. The evening before the stage, Alaphilippe’s team-mate Bob Jungels texted him and said, “You’ll win the stage, but yellow is going to be tricky…”

Alaphilippe texted back: “I’m going to try, bro. I’ve got the rage.”

The Frenchman often talks about his ‘rage’ in interviews. It directly translates as ‘rage’ or ‘fury’, but there’s an element of passion in this context which Alaphilippe describes as his motivating force. In defeat, it used to externalise itself in that handlebar banging, but used positively it’s a method of propulsion.

The novelist Graham Greene once wrote: “If you are seeking the truth, champagne is better than a lie detector. It encourages a man to be expansive, even reckless.”

Indeed, Alaphilippe was in expansive, even reckless mood as the peloton approached the finish of stage 3. Instead of waiting for the final climb, the Frenchman, his confidence underpinned by knowledge of the route, attacked on the Côte de Mutigny, 16km before the end. The terrain was more favourable than it might have seemed – Mutigny was steeper than the finish climb, giving him more of a springboard, and the downhill was sinuous, which suited him perfectly.

He executed a swooping descent, in which he carved a skier’s line through the corners, and chunks of time from his rivals. He gained time, resisted the pursuit and finally, all elbows and knees, jabbed his way up to the finish line. It was everything that Alaphilippe is good at, rolled into 20 minutes of racing.

“Champagne runs in his veins,” wrote a giddy editorial in L’Équipe the next day. Not enough people noticed, but the gradient of the Côte de Mutigny was 12.2 per cent - exactly the same as champagne.

“It was a magnificent day,” says Alaphilippe. “It was sunny; it was a stage which was really, really well suited to me. I knew I would have my work cut out but it was clear in my head. We’d done the recon and I knew that if I felt good I could do what I wanted. If you look at the final, I could have waited for the sprint. It was a puncheur’s finish. But I felt good. I did a good climb and a good descent and immediately got a large enough gap. It transcended me. I didn’t ask any more questions after that - I just rode at my maximum.

“There are so many memories of it, but the biggest is getting the jersey at the end after making a really violent effort.”

This ability to dig deep, in Alaphilippe’s view, comes from the ‘rage’. “At this level, we are all strong, we all have physical attributes which are above average, we all work hard to be at this level and to get stronger,” he says. “But after that I think it’s the way I race. Your spirit determines how you race your bike and what you achieve. You can be very strong, but that’s not enough. I’m far from being the strongest rider in the peloton. But I have something in me which makes me want to hurt myself and go deeper and further, to surpass myself.”

He does admit, by way of mitigation: “I have learned to ride more intelligently, to make efforts at the right moment.”

Alaphilippe’s coach, his cousin Franck Alaphilippe, says that Julian has always wanted more out of himself, and drives himself hard. “One of his strongest qualities is that he always wants more,” Franck told L’Équipe last summer. “When he was young, if I wanted him to ride 100km, I told him to ride 80, because then he would ride 100. If I’d said to ride 100km, he’d have ridden 120. He has always been up against riders who are similar to him, but the difference is his rage. He can go deep into pain.”

The L’Équipe writer Alexandre Roos, who does the colour stage reports at the Tour, compared Alaphilippe to a ‘jukebox on legs’. As well as conveying the Frenchman’s ability to dictate the shape and mood of a race, not to mention that of the fans, it also reminds us of his unusual background and gives us some more clues about why he is the way he is.

Alaphilippe’s upbringing is often described as ‘bohemian’. His father was a band leader in Montluçon and the young Julian initially played, gravitating to the drums after failing to be engaged by learning solfeggio. To play drums takes two things - boundless energy and refined co-ordination - and Alaphilippe had both.

So we stand back from the life of Julian Alaphilippe, see that he was raised in the milieu of concerts and music, observe that his way of racing is expressive and creative, and conclude that there is significant overlap between these aspects of his life. The creative soul is a creative cyclist, unbound by the tactical strictures of racing orthodoxy.

However, anybody who plays music knows that before the colour and beauty come hard work, discipline and rigour.

“I hope that people know how much work goes into it,” says Alaphilippe. “On the bike, in life and in music, it’s obvious you have to work a lot and have lots of discipline. Music is freedom and pleasure. The bike is the same. I get pleasure, but you have to have discipline. To get to a high level in music, it has to be perfect, and right - you can’t just play anything.

“There’s freedom, pleasure and even madness in cycling, but you can’t forget the work.”

Alaphilippe has always been a hard worker, even if this prosaic fact sometimes gets lost in the excitement about his talent. When he was a junior building up to the Junior World Cyclo-cross Championships, he worked full-time as a bike mechanic at a shop while studying for his CAP diploma. Then he went out training in the cold and dark his father following in the car so that he could illuminate the way with his headlights. He still trains very hard. There’s a saying among musicians that a keen amateur will practice until they get a piece right; a professional will practice until they can’t get it wrong.

Physically, Alaphilippe is not so imposing. He’s wispy and slight, but he visibly grows in stature when he’s on the bike, and his charisma makes him a star. Of course, this makes him the centre of attention in his home country, especially during the Tour.

This is in part mitigated by the fact that Pinot, and to a lesser extent recently Romain Bardet, also share the pressure. But Alaphilippe had more column inches devoted to him through his spell in the yellow jersey last year than either of these riders, even with Pinot looking like a better prospect for the GC before injury forced him out of the race.

Alaphilippe is comfortable with the attention without seeming to need it. In this respect he is different from his forebears as national darlings, Thomas Voeckler and Richard Virenque. There was always a feeling that France loved these two riders but also felt a sense of protectiveness - in Voeckler’s case because his physical abilities always seemed far outstripped by his ambition; in Virenque’s case because he was a boy in a man’s body. Alaphilippe has full ownership of his charisma.

He also won’t be put in a box. He denied he was riding the 2019 Tour to win, and with the benefit of hindsight, he’d been matching and beating his rivals every time there was a 20-minute effort, but when the 40-minute-plus climbs of the Alps loomed, he was always going to come unstuck. But he also won’t be typecast as an Ardennes specialist, or anything else. He wants to win anything and everything he sets his mind to.

“I’m more in the mindset of winning as many races as possible,” he says. “Winning Milan-San Remo was an exceptional moment in my career, and it gives me motivation to go and win other monuments. I’m more interested in winning more of these races than going back to win San Remo several times.

“I’d love to win Liège, Lombardy… These races suit me well and they also have prestige and a special atmosphere so to have them in my palmarès really motivates me.

“To win the Tour de France I need the right course. I think it’s something I’m capable of doing. If I achieve my goals in the classics and monuments, I would need to ride a little differently and see things differently if I ride for GC. I’d have to make a lot fewer efforts of the kind that until now I have been used to making. It’s possible, but it’s not what I’m doing at the moment.”

In the early days of the 2018 Tour, over the climbs of Brittany, Alaphilippe had been expected to thrive, especially on the uphill finish in Mûr-de-Bretagne, yet he fell short. But instead of winning the puncheurs’ stages, he won two mountain stages from breaks and the polka-dot jersey. The following year we expected more mountain stages and the polka-dot jersey; instead we got two weeks in yellow and a time trial win. Whatever we expect from Julian Alaphilippe, he’ll always find a way to surprise us. But not himself.

If you like what you read, why not subscribe to Procycling magazine? As part of our autumn sale, a subscription currently starts at just £5 for the first five issues - that’s only £1 per issue. Procycling magazine, the best writing and photography from inside the world’s toughest sport.

Edward Pickering is Procycling magazine's editor. He graduated in French and Art History from Leeds University and spent three years teaching English in Japan before returning to do a postgraduate diploma in magazine journalism at Harlow College, Essex. He did a two-week internship at Cycling Weekly in late 2001 and didn't leave until 11 years later, by which time he was Cycle Sport magazine's deputy editor. After two years as a freelance writer, he joined Procycling as editor in 2015. He is the author of The Race Against Time, The Yellow Jersey Club and Ronde, and he spends his spare time running, playing the piano and playing taiko drums.