Jan Ullrich comes in from the cold

An exclusive interview on his doping, Armstrong and German cycling

Athletes die twice, so the adage goes, the first time on retiring. It can be a curious kind of an afterlife, mind, particularly in professional cycling. Some erstwhile denizens of the peloton remain tightly involved in the sport, as managers, mechanics or media pundits. Still more linger around the fringes, lining out at a sportive here, shilling for a sponsor there, never quite cutting the ties completely.

Others seek careers elsewhere, but few, it seems, leave cycling altogether.

Even Riccardo Riccò, banned until 2024, and Danilo Di Luca, banned for life, enjoy posthumous existences as outlaws of the cycling world. Two years ago, Riccò set himself the quixotic – and ultimately aborted – task of breaking record times on a series of climbs, including Mont Ventoux. Di Luca continues to market his own brand of bicycles and published a memoir ahead of this year's Giro d'Italia.

When Operacion Puerto abruptly pulled the shutters down on Jan Ullrich's career on the eve of the 2006 Tour de France, it initially seemed as though the German might become that rarity – a professional bike rider cast definitively into the wilderness as a result of a doping infraction.

That summer, faced with evidence that he had received blood transfusions from Dr. Eufemiano Fuentes, Ullrich issued the unconvincing denials that are seemingly expected of a man in such a position, but largely retreated to his home on the Swiss side of Lake Constance thereafter.

Ullrich would remain cloistered there, at least as far as the cycling world was concerned, for the years following the formal announcement of his retirement in February 2007. As each fresh scandal emerged – Michael Rasmussen's whereabouts, the CERA positives, Lance Armstrong's contentious comeback – Ullrich seemed to recede further into the background. He chose silence, even as those in his homeland prodded for an admission of guilt.

"Once I asked a guy, 'Do you want Jan to end up like Pantani or Jimenez? Would that make you happy?'" Ullrich's friend and former Telekom teammate Andreas Klöden complained of the German media coverage in 2010. "It's four years now and Jan has paid a lot. He only wants silence for his family."

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

What a difference a belated and partial confession can make. In June 2013, five months after his old rival Armstrong had yielded to the inevitable and acknowledged that he had cheated his way to seven Tour wins, Ullrich finally admitted to Focus magazine that he had doped under Fuentes' supervision, saying: "I didn't take anything that was not taken by the others."

The rehabilitation started there, aided, perhaps, by how brazen Armstrong had been, in both his doping and his denials. By comparison, the meek Ullrich, Tour winner in 1997 but beaten five times by Armstrong afterwards, was cast in a decidedly more sympathetic light.

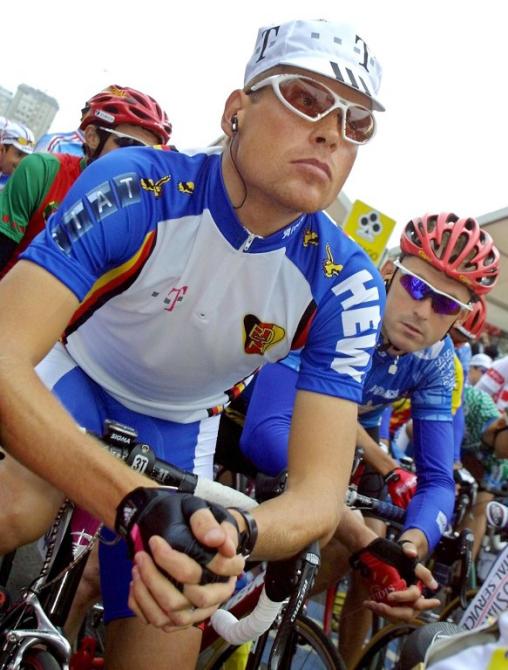

By February 2014, Ullrich was a brand ambassador for Storck bicycles and had been pictured being fitted for Rapha kit. Already a tentative participant in leisure rides, initially under the pseudonym of Max Kraft, he began making ever more regular and public cameos at sportive rides the world over.

Just when he thought he was out, Ullrich pulled himself back in.

The long way back

For two days last week, Ullrich was in London as a guest at the Rouleur Classic, an event which mixes high-end bike and clothing manufacturers hawking their wares with talks from professional riders past and present.

On Friday evening, for instance, the former US Postal rider Viatcheslav Ekimov made a presentation entitled "2017 for Katusha." The previous day, Team Sky had unveiled a new jersey, an occasion replete with the usual incomprehensible psychobabble. Sean Kelly, Giovanni Battaglin and Graeme Obree were among the speakers, but then so too was Graham Bartlett with an infomercial for the Velon group.

Ullrich, for his part, was on hand for two question and answer sessions, flanked by Markus Storck, CEO of the eponymous bike company. A few pounds heavier than in his heyday but decidedly lighter of bearing, Ullrich cut an avuncular figure on stage, repeatedly apologising for his English and laughingly dusting off some old tales from his career.

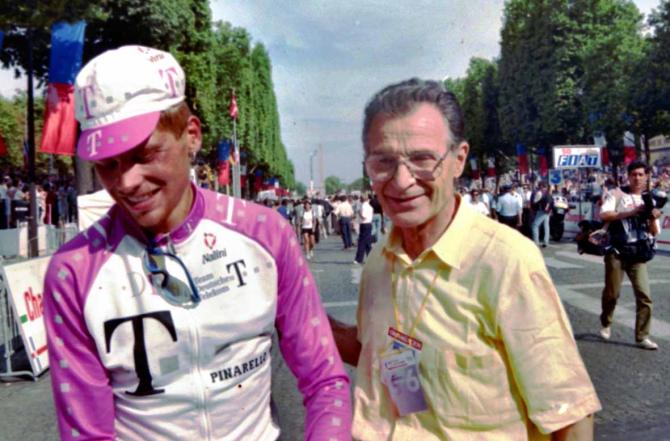

He had a sense of comic timing, too, breaking into a rueful smile when it came to talking about what he termed vaguely as his "problem in 2006" and the general sense of bonhomie remained undimmed even through a couple of follow-up questions. Off stage, Ullrich posed gladly for selfies with punters who had stumped up to attend the event, and indulged the fan in himself, too, when he asked to have his own picture taken with Miguel Indurain's famous Pinarello Espada, part of a display of historic bikes.

After his second talk, and before leaving for the airport, Ullrich sat down – briefly – with Cyclingnews to run the rule over the ten years since Operacion Puerto and his apparent re-acceptance into the fold.

"I am very happy now," Ullrich said. "I have a great wife, I have four kids. I live in Mallorca in Spain, and I am happy with my life."

The period immediately after Operacion Puerto exposed his doping was rather different. Ullrich had already planned to retire from cycling in 2007, and from a purely sporting point of view, ending his career a season early was no tragedy. "I was at the finish of my career in 2006. I was not young, I was not hungry. I wanted to stop either that year or the following year," he said.

Ullrich had seemingly not counted, however, on retiring with a tarnished legacy, and he drifted into relative solitude in the years that followed. The headlines gradually abated, resurfacing only when he lost a defamation suit against anti-doping expert, for instance, or when it emerged that he was suffering from stress-related burn-out. Ullrich, predictably, now cites the German media as cause of many of his problems in that period.

"There are some people in the press in Germany – it's only five or six people in the press – and they make pressure for me every time," he said. "In this time, too, with the start of the Tour de France [in Germany next year] it's 'Oh, you know Ullrich ten years ago…' This is not good for the sport."

At the time, Ullrich's four-year lost weekend after the end of his career had the feel of a man going into hiding due to the feelings of shame and embarrassment. In 2016, he limits himself simply to pointing out that he felt he needed a break after so much time in the spotlight. A Tour winner at the tender age of 23, Ullrich had, after all, spent a decade in the public eye, by way of yearly inquisitions into his early-season weight and a doping ban in 2002.

"The first four years were very heavy for me, it was a bad time. But what helped me in that time was the normal fan, the people who watched me on TV or came to the Tour de France to watch me live. In this time, they were still fans," he said. "I was asked to sign a lot of autographs in that time. The people helped me a lot but the press was very bad to me. And that lasted for a long, long time."

Considering the warmth of the reception he has received in London and elsewhere, one wonders if Ullrich might have been better served by immediately admitting to wrongdoing rather than waiting until he had almost turned 40.

"It was not possible in this time," he said. "I needed my break and I was in my private sphere in this time. But the last six years have been beautiful. I've been building my own life, cycling with people all over the world, it's a very good thing."

For all that Ullrich was pressed briefly on Operacion Puerto during his second session in London, it was still rather disconcerting to see a confessed doper holding court at a Q&A that was billed simply as "A Brilliant Career." It is difficult to imagine that Floyd Landis, say, or even Armstrong himself, would be afforded a title that airbrushed history to such an extent.

Forever the 1997 Tour de France winner

But then again, while Armstrong's seven Tour wins have been excised from the record books, Ullrich remains forevermore the maillot jaune of 1997. Ullrich can only laugh when asked whether he thinks it is correct that the roll of honour remains empty for the years 1999 through 2005, while he – and many, many others – retain their places in the Tour pantheon.

"That is not my question, that is not my question. Lance was special. Lance was special," he said. "He became the money, he was the boss for all the team, he brought riders into the team, he was the big boss. He made the mistakes alone."

A comparison of generations

While Ullrich's inference here seems to be that he was simply a cog in the doping machine at Telekom rather than one of its principal architects, he suggested that cycling's EPO generation had been unfairly singled out for punishment given that, in comparison with other eras in cycling, the only material difference had been the strength of the poison on offer.

"You know that we have Eddy Merckx, and Eddy Merckx was one or two times positive," Ullrich points out. "For me it's not good that the Tour de France has no winner for seven years. This is not good for the history. But we know it all, we know the stories. I'm not the man who makes the rules."

Even when Ullrich confessed to doping in 2013, he refused to call it cheating. "In my view you can only call it cheating on my part when it is clear that I have gained an unfair advantage. That was not the case," he said at the time.

It is true, certainly, that nobody would ever step forward to claim the 1997 Tour on behalf of Richard Virenque or Marco Pantani, nor have Andreas Klöden or Alexandre Vinokourov – then teammates at Telekom – ever sought to upgrade their medals from the Sydney Olympics, when they finished behind Ullrich in the road race. But what of those few riders of the era, Christophe Bassons, for example, who resisted the pervasive call to arms?

"I think the problem was with the system," Ullrich said simply. "All the years, if you look in cycling, football and other sports, it's a big problem in all the system, in all branches."

Ullrich has been in a system of one variety or another for most of his life. In East Germany, his ability on a bike saw him brought as a 13-year-old from Rostock to Berlin, so that his talent could be developed further. Ullrich and elements of that system – some good, others bad – found a home after the fall of the Berlin Wall at Telekom, and success followed.

Even after the events of 2006 saw Ullrich thrust outside of the system altogether, he continued to abide by its old rules, keeping his mouth shut and gamely going through the motions of fighting sanctions through the courts. Where Landis looked to tear the house down, Ullrich held his counsel.

If Armstrong's downfall unlocked the door, then Ullrich's low-key confession shortly afterwards nudged it open. Now back across the threshold, Ullrich is not of a mind to cast aspersions on the credibility of professional cycling in 2016.

"I don't want to think this," Ullrich said smilingly. "I never think when I see Froome or something, whether he's doping or not doping. I just watch the race, the sport only.

"I like the sport, and the Tour de France is the biggest event after the World Cup and the Olympic Games. This is a big sport and you see all the people buy expensive bikes and all. This is a very good sport for kids and for old people and you must see that, not this doping or not doping."

Being part of the 2017 Tour de France Grand Depart

The 2017 Tour will get under way in Düsseldorf, and while ASO has billed it as the 30th anniversary of the last German start, in West Berlin, it will also mark a milestone that the organiser seems rather less keen to commemorate.

Not a single official communique has mentioned that come July, twenty years will have passed since Ullrich became the first and only German winner of the Tour de France. His victory heralded German cycling's boom years, and his subsequent fall convinced local sponsors to tiptoe away.

The recovery of German cycling has been slow, but momentum has gathered quietly. It remains to be seen whether an official invitation to the festivities will be forthcoming, but, one way or another, Ullrich will be on hand in Düsseldorf on July 1.

"Absolutely. From my side, I was not ready to go back in professional sport. I watched all the races on the TV and I didn't go directly on the Tour de France. But next year is twenty years from my win and the Tour starts in Germany. I can help there," Ullrich claimed.

"I have an all-star race before the start with Indurain and all the big heroes. We can make a lot of good things there."

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.